The Narwhal’s in-depth environmental reporting earns 11 national award nominations

From disappearing ice roads to reappearing buffalo, our stories explained the wonder and challenges of...

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter.

Maurice Ruddick waited for nearly nine days near the bottom of a 4,300-metre-deep coal mine before he was rescued. An underground earthquake brought down ceilings and pillars and shifted debris into tunnels, trapping Ruddick and several other miners. Stuck in the darkness, with limited food and water Ruddick lifted his fellow miners’ spirits by leading them in prayers and song.

In 1958, Nova Scotia’s Springhill mine disaster killed 75 men and trapped dozens in the tunnels. The world kept vigil for survivors as they were slowly rescued. Ruddick, a descendant of enslaved Black people, was among the last miners to be brought back to the surface. A media circus followed and the survivors’ stories were broadcast around the world.

“Maurice’s story is often celebrated for his heroism during the Springhill disaster but less attention is paid to the broader context of racial discrimination he faced,” Aderinola Olamiju told The Narwhal. Olamiju, a graduate student at Memorial University in Newfoundland, is researching the history of Black miners in Nova Scotia.

“As an example, after the rescue, when he and other survivors were meant to travel to Georgia for vacation, there was still segregation in the United States at that time and he had to be housed separately from the white miners.”

Ruddick’s story is one of the most well known of a Black miner in Canada. It was made into a Heritage Minute, covered in books and is now a musical play. Olamiju, originally from Nigeria, is looking to explore lesser-known stories.

As he digs through archives, libraries, union pamphlets and historical newspapers, he hopes to uncover “the hidden stories of Black miners in Nova Scotia’s industrial past, particularly how racial dynamics influenced their experiences with workplace safety and health risks.”

The Narwhal spoke with Olamiju about his research into what life was like for some of the first Black miners in Canada and the challenges of trying to piece together this history. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

As part of the Mining Danger project, which investigates the history of accidents, occupational disease and pollution in Canada’s mines and mining communities, the main focus of my research is looking at the racial dynamics of mining labour, particularly how it connects to health and risk.

My research will examine several key questions, but the main ones are: how did coal mining companies, labour recruiters and government institutions together create and reinforce racial hierarchies within the industry? And how did Black workers engage with unions and workplace advocacy to improve their working conditions and address workplace accidents and issues relating to occupational health?

Historically, the coal industry in Nova Scotia was intricately linked to the steel industry, as coal was used to burn the furnaces in the steel-making process. So you had two industries heavily dependent on each other. During the industrial expansion of the 1880s and 1890s, there increasingly became labour shortages in the coal industry. Companies like Dominion Coal (Domco, later Disco) and Nova Scotia Steel and Coal Company (Scotia) emerged as major players in the 1890s, and they turned Cape Breton into this industrial hub where you had rival companies running both steel and coal-mining operations.

To address these labour shortages, some of these companies began to recruit labour from outside the country. Disco was actually a major facilitator of Black migration to Nova Scotia through agreements with the provincial government. The recruitment process sometimes used established networks within the North American steel industry, with company managers recruiting workers from industrial centres in Alabama, Buffalo, Maryland and Pittsburgh.

Other times, you had labour recruiters going directly to Caribbean countries, and workers who returned home would also recruit their friends or families. As many Caribbean countries were colonized by the British at the time, it was easier to recruit labour from the Caribbean, particularly from Barbados and Jamaica. Nova Scotia’s location and shipping networks made this connection and recruitment easier and labour migration wasn’t only limited to the coal and steel industries. Domestic workers, particularly women, were also recruited from the Caribbean to work in Nova Scotia.

We know these new labour recruits faced multiple layers of racial discrimination. Just like in our contemporary society, back then Black labour was devalued as Black workers were often paid much less compared to their white counterparts. Despite having skills, Black workers faced this constant discrimination that kept them in subordinate positions, doing the most physically demanding and lowest-paid jobs. During boom and bust cycles, these workers were often the last to be rehired and the first to be fired.

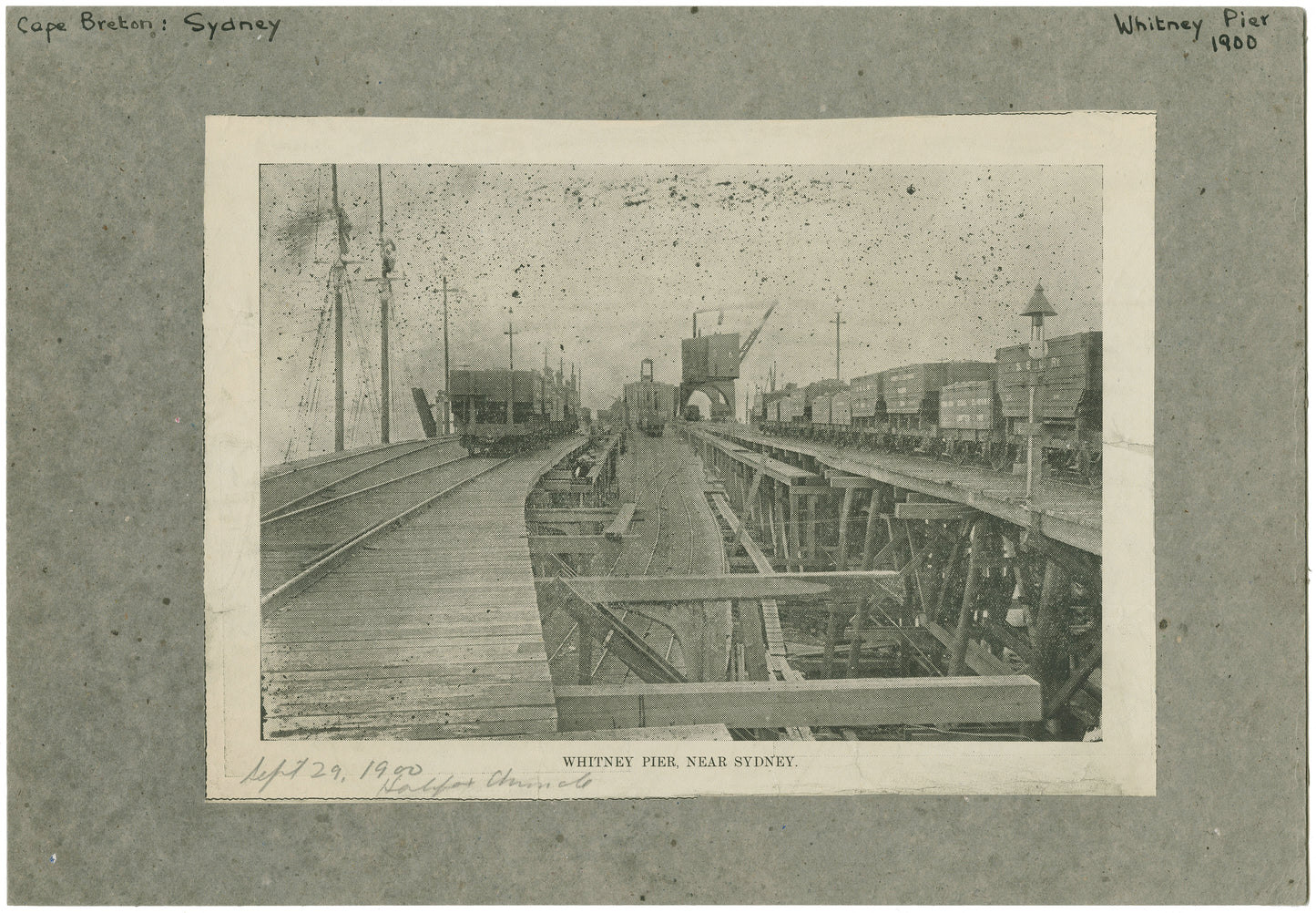

Their housing situation was also subpar. For example, for some Disco workers, many lived in company shacks in the Cokeville section of Whitney Pier that lacked basic things like proper heating and running water. There’s this letter from 1908 where a blast furnace superintendent, J. McInnis, wrote to the general manager about how bad the houses were in the “Negro quarter” — they were unboarded and exposed to the harsh realities of winter weather.

The work itself was extremely dangerous, especially at Disco’s blast furnaces and coke ovens. Black workers were concentrated at these positions because of racial stereotypes about their ability to withstand heat better than white workers. But despite all these negatives associated with labour and immigration, Black workers managed to build strong communities. They set up churches, schools and businesses to help each other cope with the challenges of industrial work and discrimination.

Seeing how racial dynamics developed in Nova Scotia and what forces and factors shaped them. You had these companies actively recruiting Black workers from the Caribbean and the United States to address labor shortages, while at the same time Canada’s immigration policies were trying to restrict Black migration.

What’s particularly striking is how similar these dynamics are to what we see today — there’s still this tension between the economic need for immigrant labour and anti-immigrant rhetoric.

Over the summer months, I will be conducting research at various archives and libraries in Nova Scotia, including the Nova Scotia Archives and the university archives at Dalhousie and Cape Breton. Some of the most important sources will be company records, print newspapers and magazines and union documents. Canada’s immigration records are also useful in understanding the policy of immigration discrimination based on race and looking at the scale of migration and countries of origin.

Generally, the historical record of such stories is often fragmented. Racial discrimination affected what stories were told and kept in archives. Sometimes the most valuable information can be found in places like immigration paperwork or company letters, rather than the usual mining narratives. Archives also may only keep what society at that time deemed important.

Another factor is scale. Compared to white workers, there weren’t that many Black workers in Nova Scotia’s mining industry. The Afro-Canadian population in Nova Scotia is significant and has a rich history, yes, but when it comes to mining specifically, their numbers were smaller. This was partly because of Canada’s immigration policies — immigration agents were actually given secret instructions to keep Caribbean Black people out, even when they met all the official requirements. They would even work with U.S. officials to restrict African-American migration by getting American railway companies to increase ticket prices for Black passengers from $20 to $200, for example.

Updated on Feb. 28, 2024, at 10:45 a.m. ET: The subtitle on this story was updated to clarify the researcher interviewed for this story is based in the Altantic region, not the Maritimes. He is based in Newfoundland and Labrador.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

From disappearing ice roads to reappearing buffalo, our stories explained the wonder and challenges of...

Sitting at the crossroads of journalism and code, we’ve found our perfect match: someone who...

The Protecting Ontario by Unleashing Our Economy Act exempts industry from provincial regulations — putting...