This article is from Hakai Magazine, an online publication about science and society in coastal ecosystems. Read more stories like this at hakaimagazine.com.

The dead oyster falls from the plastic mesh bag with the hollow clop of a horse hoof on pavement. Its shell gapes, innards rotted. About 100 or more oysters — some living, some dead — quickly follow, clattering like maracas onto the flattened bow of Joe Googoo’s dark-green jon boat.

Clad in a jacket with blaze-orange sleeves and a ball cap with a moose on it, Googoo pulls a knife from his belt holster in one smooth motion and taps oyster shells with its curved tip as he sorts through the mottled pile. Counting them one by one, he tosses lifeless shells aside and puts the living oysters back in the bag.

Beside Googoo, Robin Stuart, a large, curly-haired man in a tattered black-and-blue drysuit, perches on the boat’s edge. Stuart, one of Nova Scotia’s most experienced aquaculture experts, cracks jokes as he, too, picks around for “morts” — mortalities.

“If you could grow an oyster big enough, Joe would be buried in it,” he says with a chuckle. As the longtime friends tally the dead, Stuart soon grows somber. “There’s almost as many morts as there are live,” he says in his gravelly Scottish-Welsh brogue. “MSX is definitely doing its thing here.”

Bras d’Or Lake, cupped within Nova Scotia’s Cape Breton Island, is actually a sprawling, semi-enclosed tidal network of bays, estuaries and ponds scraped out by glaciers at the end of the last ice age. On its muddy bottom, Crassostrea virginica oysters once grew as big as brunch plates, with frilly shells and deep, round cups: qualities prized by oyster connoisseurs.

For decades, the Bras d’Or oyster industry blended wild-caught harvest and aquaculture; locals picked oysters from public beds while commercial growers cultivated the shellfish in vast beds on the lake’s bottom and transferred them onto floating rafts to await packing and shipping.

Many harvesting families, including Googoo’s, are Mi’kmaq, and have lived near the Bras d’Or — which they call Pitu’paq, or “to which all things flow” — for thousands of years. While never a staple, oysters are a fundamental part of Mi’kmaw food traditions and philosophy, with many families harvesting them year-round for personal consumption.

So when the commercial oyster industry took off in the 1950s, many were well positioned to sell oysters for a living. At the industry’s peak, estimates Stuart, more than 100 Cape Breton license holders — commercial and recreational, Mi’kmaq and non-Indigenous — had millions of oysters on their farms, collectively worth millions of dollars.

Then it fell apart.

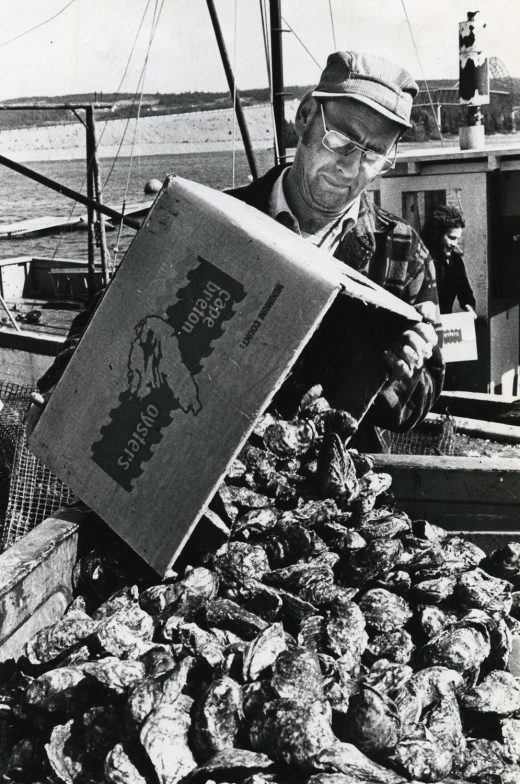

Oyster Farming, Eskasoni, ca. 1980. Photo: Owen Fitzgerald, 94-651-25166 / Beaton Institute, Cape Breton University Oyster Farming, Eskasoni, ca. 1980. Owen Fitzgerald, 94-653-25168 / Beaton Institute, Cape Breton University

In the summer of 2002, a mysterious and deadly invasive parasite called multinucleated sphere unknown, or MSX, flattened Cape Breton’s oyster industry. Within months, millions of oysters died, their internal organs devoured by the parasite.

Mortality of infected oysters hovered around 90 per cent. Nearly all of Googoo’s 400,000 oysters died.

“It was devastating,” says Anita Basque, who at the time was fisheries manager for Potlotek, a Mi’kmaw community on the Bras d’Or’s south shore. Like many others, she grew up picking oysters as a little girl and bringing them home to her mother for a quick snack. She also helped Googoo’s father sell shucked oysters, packaged in glass jars, at the Googoo family’s roadside shop. Later, as a single mother, she supported her three children with money she made diving for and selling oysters, before she became a bank teller.

When Basque eventually took over as her band’s fisheries manager, she met Stuart, who was already well respected in Nova Scotia’s aquaculture scene and helped secure oyster leases for the band.

A new oyster processing facility Basque initiated launched in 2002 with a grand celebration; within months, the industry collapsed due to MSX.

“I was so broken up,” says Basque. “My hopes and dreams for the whole community were squashed.”

Cape Breton oysters are no longer sold commercially, and the industry has been essentially dead for nearly two decades. Googoo and Basque, who both once held profitable leases, say their kids and grandkids have a hard time understanding their nostalgia.

Now, in a last-gasp effort to revive commercial oyster growing in the Bras d’Or, a makeshift team of scientists, community members, and oyster harvesters is fighting to understand and evade MSX. Coordinated by Cape Breton University assistant professor Rod Beresford, theirs is a supergroup of sorts, relying on high-tech devices, traditional knowledge and elbow grease.

It’s a collaboration Basque calls “true reconciliation.” And what they’ve found so far could bring the Bras d’Or oyster industry back from the dead.

_______

On the group’s second day of fall sampling, Beresford joins Stuart, who is paid for his on-site work, and his lab technician Sindy Dove at a chilly beach on the north side of the Bras d’Or, far across the lake from Googoo’s leases. Beresford avoids getting in the water if he can, so watches the two others scramble along the beach toward a buoy marking the site’s four cages: two floating near the top, two resting on the murky bottom.

Beresford, who is also a researcher with Cape Breton’s Verschuren Centre for Sustainability in Energy and the Environment, marvels at what brought him to this moment: from studying a creature he doesn’t like to eat to buying a black tie emblazoned with Save the Oysters for his PhD defense.

Watching Stuart wiggle into his drysuit from afar, he confides that he’s never been particularly interested in oysters.

But he is interested in solving scientific mysteries.

For decades, the origin and behavior of MSX has been a “real head-scratcher,” says Beresford, although some scientists believe that the parasite first hitched a ride to North America in the ballast water of U.S. warships returning from Japan and Korea after the Second World War.

Scientists first identified MSX in Delaware Bay, south of New Jersey, after it wiped out thousands of oysters there in 1957. Within decades, it spread, infecting oysters from Maine to Florida. On how the parasite made it to Cape Breton, Beresford says there are two theories: it arrived either in ballast water or via an infected oyster introduced from farther south.

Viewed under a microscope, MSX is “almost a perfect circle, like an emoji [face],” he says. When eaten, it’s harmless to humans. But once MSX infects an oyster, the parasite quickly starts to consume the creature’s soft innards. Once the oyster loses its digestive organs, it essentially starves to death.

Because oyster immune systems don’t have a “memory,” a weakened oyster that survives its first MSX infection is more likely — not less — to die from a subsequent infection.

As Beresford pondered the puzzle of the Bras d’Or oysters, eventually connecting with Indigenous knowledge holders including Googoo and Basque, he formulated his theory: perhaps the lake’s muddy substrate — the soft bottom that nurtures those gorgeous shells — is exactly where MSX lurks. And perhaps certain specific salinity levels and temperatures, which vary as wildly as the lake’s diverse bays and inlets, either help or hinder the parasite.

If he could keep oysters alive just below the lake’s surface, he speculated, maybe he could prevent them from catching the parasite in the first place and eventually revive the region’s oyster industry.

It was an ambitious proposal predicated on a simple experiment: with Stuart’s expertise, and cooperation from leaseholders who had held onto decades-old government plots, Beresford and his team chose a dozen test sites across the Bras d’Or. Googoo, who, after MSX hit, had figured out how to grow thousands of oysters in a protected bay for his own consumption, collected spat and 24,000 native oysters for the project.

The team packed cages with 500 oysters each, zip-tied temperature and salinity loggers resembling large black glow sticks to each one, and then sank two to the muddy bottom and floated the other two near the surface at each test site.

Then they waited.

_______

Stuart’s work counting dead oysters and taking samples, on that misty morning with Googoo on the Bras d’Or, will provide the first glimpse of whether or not Beresford’s theory holds. At two of the sites, oyster mortality at the bottom hovers between 40 and 60 per cent. Yet only a few dozen of the oysters floating near the surface have died.

The difference, Googoo says, validates what he’s been insisting all along, that oysters can survive in the Bras d’Or in the right locations.

Beyond the promise of reviving a culturally important Mi’kmaw tradition and a critical component of their lake’s ecosystem, the project is also an act of amity. Basque later tells me that working with Beresford’s team has been refreshingly devoid of the condescension and sidelining she often experiences from non-Indigenous academics and so-called experts.

Standing beside his boat on shore, Googoo, who claims he’s too old for politics or bureaucracy, says he feels the same. “They’ll listen to me and my ideas,” he says, surveying his oyster lease. “I’m the one out in the field [every day], not them.” He taps his knife against the shells, listening for the hollow, disheartening clunk of another dead oyster.

Beside Googoo, Dove — Beresford’s lab technician — scrubs barnacles and debris off a temperature logger with a toothbrush. Recently, says Stuart, the expensive devices have been disappearing. They may have fallen off, or, as he suspects, been stolen or vandalized by disgruntled non-Indigenous locals or bored teenagers. “We’re going to have to put cameras out,” he says.

In recent months, Mi’kmaw fishers across Nova Scotia have exercised their legal, federally protected moderate livelihood fishing rights by catching and selling lobster outside of the non-Indigenous commercial season. In late 2020, protests erupted in violence and vandalism along the province’s south shore, and Stuart says similarly hard feelings have been felt here.

Stuart displays a sea star retrieved during his work hauling in oyster cages. Photo: Darren Calabrese An oyster cage, fit with flotation devices, is hauled in from the bay. Photo: Darren Calabrese

Frequently, Beresford fields questions about his work from other university researchers, who say they admire the trust and camaraderie he’s earned from his Mi’kmaw collaborators. Basque often hears the same thing, but is baffled why others find the relationship so elusive. “It all comes down to respect,” she says.

Although his team is behind on analyzing tissue samples — the testing facilities are currently backed up due to COVID-19 — Beresford is optimistic that he’s close to pinning down the sweet spot of temperature, salinity and depth that would protect oysters from MSX. He believes oysters grown near the surface, where temperature and salinity often vary widely, will have the best chance at survival.

Other areas hard hit by the parasite, including parts of the United States, could then use the findings to revive their own industries.

Most importantly, Beresford says, it means their team is getting closer to helping people like Googoo and Basque realize their long-deferred dream of reviving the Bras d’Or oyster industry — backed by science, and hopefully built to last.