Last December, Hassaan Basit was awaiting the passage of an omnibus bill by the Doug Ford government that would limit Ontario’s conservation efforts.

As the CEO of Halton Region Conservation Authority, Basit was concerned about a number of proposals in the bill, including one amendment that could disempower conservation authorities like his in matters of development across wetlands.

Then, on the eve of the bill’s passage, he got a phone call.

It was then-environment minister Jeff Yurek asking Basit if he would help figure out how conservation authorities could work with and implement the new regulations.

That phone call marked a turning point in the contentious relationship between the Doug Ford government and conservation authorities.

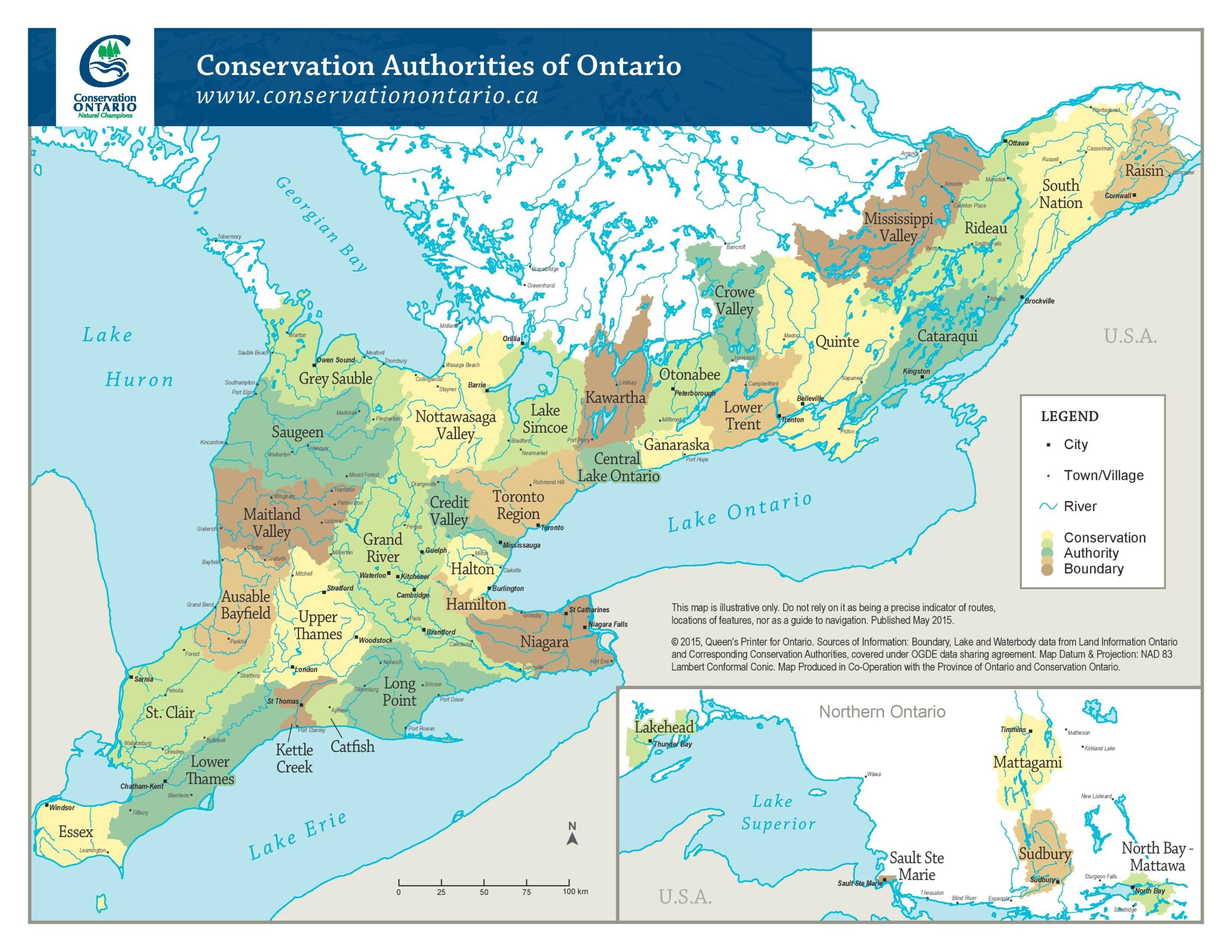

Basit was pleasantly surprised. Just four months prior, the government had sent Ontario’s 36 conservation authorities — who operate more than 500 conservation areas, and oversee everything from wildlife management to floodplain mapping and monitoring, to watershed protections and more — a letter ordering a “wind down” of all unnecessary programming, as part of its broad efforts to eliminate Ontario’s deficit.

The letter identified these activities as zip-lining, maple syrup festivals, kayaking, photography and wedding permits — all sorely needed revenue-generating activities.

“For far too long, our conservation authorities have strayed from their mandate. That’s why we have flooding in basements,” Government House Leader Paul Calandra said in a November 2020 question period when asked about this move. “What we’re doing is strengthening conservation authorities to … bring it back to its core mandate.”

At no point did the government acknowledge that earlier that year it had slashed conservation authorities’ funding for flood management programs — part of their core mandate — in half.

“It was just odd to get that out of the blue,” Basit said of the letter. “It was very surprising and unreasonable. The concern was that this signaled some sort of intent to use legislative tools to force conservation authorities to basically stop working.”

Basit and fellow conservation heads came together to write a letter of their own to the premier, one that was also signed by almost every mayor across the province. In it, they outlined their deep concern. This note and the public outcry that followed nudged the province to back off a bit, taking time to consult with all 36 conservation authorities. Basit even went to Yurek’s Bay Street office to have a frank conversation about the actual improvements and changes the conservation authorities needed. Despite all this, the bill passed as is.

For Basit, the phone call that came four months after this meeting, asking him to head a working group for these regulations, was a rare act of “sincerity” and “a willingness to collaborate” from the Ontario government — a complete 180 degree-shift from an otherwise tense and imperfect relationship. For many in the conservation space, the working group would be the very first time they had a clear channel of communication with a Ford government minister, a space to explain the impact of some of the proposed environment and conservation changes.

Since January, the Conservation Authorities Working Group has biweekly brought together conservation experts, developers, urban planners, agricultural representatives and two consecutive provincial environment ministers. They’ve combed through the nuts and bolts of the new regulations that were buried deep within omnibus budget Bill 229 — regulations that led to the mass resignation of seven members of the Ontario Greenbelt Council who are appointed to advise the environment minister on land management in the Greenbelt area that overlaps several conservation authorities. These new rules, known as Schedule 6, were posited to modernize and streamline the mandate of conservation authorities, but in reality would have made their work more complicated and less effective.

For example, one of the key roles of a conservation authority is to provide independent oversight and review of development over floodplains and wetlands. Schedule 6 empowers the minister of natural resources and forestry to approve any development project with no input from them.

In the lead up to the passage of the bill, government ministers used troubling language to justify the need for the proposed changes, most of which relegated environmental protections below economic and development interests. In November 2020, Yurek told the legislature that the changes were needed because “conservation authorities were going beyond the rules and regulations of the province and instituting their own rules.” In fact, since 1946 conservation authorities have been empowered by provincial legislation to, first and foremost, protect Ontario’s natural environments. That has included having significant input in development proposals that may negatively impact wetlands or floodplains.

With cities like Caledon and Brampton, which have the highest growth trajectories in the Greater Toronto Area, already exploding into their agriculturally rich regions, conservation authorities are facing increasing pressure to yield to development despite its impact on natural environments.

Despite the tense lead-up, Basit said the working group has been “constructive.” He set the tone for their work early on, by asking everyone to focus on problem-solving over politics: the group had to learn to move past their anger that the government had passed the legislation and work to refine the way the regulations would be implemented to make them as effective and feasible as possible. Its main task was to clearly define the work of conservation authorities so that funding negotiations are easier and future pushback is limited.

The feedback about the working group is overwhelmingly positive. Kim Gavine, head of Conservation Ontario, the group that represents all 36 conservation authorities, said the group discussions are “honest, productive.” Sommer Casgrain-Robertson, general manager of the Rideau Valley Conservation Authority, said the group “has completely changed our working relationship with the provincial government.” Carl Jorgensen, head of Conservation Sudbury, said the collaboration and its results were “refreshing.”

In October, the government released the initial phase of regulations that, for the first time, clearly lay out all the work conservation authorities do, without being overly prescriptive. Casgrain-Robertson said one of the biggest outcomes of the group was “just raising the knowledge level of the ministry about conservation authorities, what we do, how we operate.” Two more phases of regulations still need to be worked through, which get into more technical things like what programs they can charge fees for and how they will administer their authority over development permits around key natural environments.

Members of the working group who spoke to The Narwhal said that a lot of credit for the success of the working group goes to Yurek, who made himself fully available to their sessions every two weeks. (Yurek’s office declined to speak to The Narwhal for this story.)

Halfway through the process, a cabinet shuffle led to a change at the helm when David Piccini took over as environment minister, but group members say no momentum was lost. In fact, Piccini delivered some bonus victories.

David Piccini steps in as Ontario’s environment minister

In an interview with The Narwhal, Piccini said he was mindful to “immerse” himself and “nerd out” over the history and work of conservation authorities so he could be a collaborative member of the group.

That history and work is vast. Ontario’s conservation authorities were created almost 75 years ago in response to concern about the environmental impact of a growing population. Collectively, all 36 conservation authorities are the second largest land-owner in the province after the Crown, in charge of 150,000 hectares of land. They are the envy of conservators around the world because each authority takes care of a whole watershed rather than areas dictated by municipal borders. After the disastrous impact of Hurricane Hazel in 1954, conservation authorities took on the work of flood-mitigation efforts. After the Walkerton tragedy in 2002, they have also been responsible for implementing the Clean Water Act.

Conservation Ontario describes them as agencies that aim to balance “human, environmental and economic needs” in collaboration with all levels of government, landowners and many other organizations. Many describe the work of conservation authorities as akin to giving the natural world a seat at the table.

“I come from a rural community so I know how important conservation authorities are,” said Piccini, who represents the riding of Northumberland-Peterborough South. Even before he became environment minister, Piccini co-hosted an engagement session in his riding with Yurek to discuss the new regulations. He said that he heard from his constituents about the challenges of a growing community that wants continued access to and protection of the natural environment.

Piccini said he and his dog Max are frequent users of the trail system managed by conservation authorities. It’s a system he saw was being used more and more by Ontarians during pandemic lockdowns, which is why he pushed to include passive recreation — hiking, fishing, canoeing and even maple syrup events, once seen as “unnecessary programming” by his government — as one of the mandatory services conservation authorities provide.

In listening to the working group’s conversations about passive recreation, Piccini said he learned that managing them was done differently around the province. Adding it to the list of core programs would mean conservation authorities don’t have to explain and defend these programs at every budget meeting with a municipality.

“Maintaining public access to nature, regardless of background, regardless of where you are in life, everyone should get to go out and enjoy our trail system,” Piccini said.

To guarantee this, he sees the province’s future role with conservation authorities as that of a collaborator.

“You’ve got to listen, and you’ve got to engage,” he said. “I think we found the right balance here of the province engaging with the working group, different players and different competencies, but also empowering municipalities to make informed decisions.”

“I’ve been doing this job for 17 years and I’ve worked with lots of governments … and both of these ministers have been really involved in this, which has been extremely helpful,” Basit said. “They’ve been very blunt about what they’ve heard but they’ve also given me an opportunity to work with them and explain the context and then made final decisions.“

While Basit says that the “heavy lifting” is over, there’s still more work to be done.

What the new Ontario conservation authority regulations say — or don’t say

One of the main points of contention in the new regulations was that government officials didn’t seem clear about what exactly conservation authorities should do, what should be funded by various levels of government and what should be left to conservation authorities to fundraise or generate revenue for.

To address this, the working group helped the government create three clearly defined categories of programs and services. The first are mandatory programs that are in line with provincial priorities like the protection of core watersheds and drinking water sources, and the mitigation of natural hazard risks.

The second two categories pertain to more local programs, like tree-planting, water quality monitoring and stewardship programs. This will require each conservation authority to develop agreements with each municipality in its region, detailing what is being offered, at what cost and how it will help the community. These agreements, a brand new requirement, need to be finalized by 2024.

As onerous as it sounds for 36 conservation authorities to develop agreements with 444 Ontario municipalities, Basit said these are “administrative exercises” that will ensure transparency and stronger long-term relationships. While the province only provides less than eight per cent of a conservation authority’s budget, municipalities make up over 50 per cent, with the remainder coming from self-generated revenue and federal grants. Now, Basit said there is “a template for conservation authorities and municipalities to really understand each other.”

“Over the years, conservation authorities have grown and prospered, many of them to a point where people sort of took them for granted,” Jorgenson said. “I think this process is going to paint a clearer picture that the programs are important and reported in the right way.”

The Luther Marsh Wildlife Management Area is a popular recreational area within the Grand River Conservation Authority’s watershed. Photo: Tina McAuley / Grand River Conservation Authority An area of the Holland Marsh, east of Bradford-West Gwillimbury, that falls under the Lake Simcoe Region Conservation Authority. Photo: Christopher Katsarov Luna / The Narwhal

For some, this exercise will be easier than others. Jorgenson only has to deal with one large municipality, Sudbury, while someone like Basit may have to deal with four or five. Some conservation authorities have to work with dozens of municipalities. “We all speak the same language and we generally do the same thing, but we’re all really different,” Jorgenson said. While some watersheds have massive flooding problems, others face soil erosion or deep deforestation. Jorgenson said these proposed agreements will ensure all conservation authorities are on the same page while giving them the flexibility they need to respond differently to their individual challenges.

Casgrain-Robertson, of Rideau Valley, said the working group really pushed for regulations that struck a balance between clear objectives and flexibility — and that the province delivered. The onus is now on conservation authorities to make a strong case about what programs are needed and how they’ll deliver them, in order to end up with strong agreements with municipalities.

Ontario Liberal environment critic Lucille Collard said she’s concerned creating these agreements will “take away from [conservation authorities’] ability to do what they are supposed to be mandated for.”

“I don’t think that conservation authorities’ main strength is negotiation, which is going to be what’s needed in trying to get these agreements with other municipalities,” she said.

Basit said it’s not “a hindrance,” as conservation authorities currently have to present their entire budget to municipal councils every year, with the goal of maintaining or increasing their funding. These multi-year agreements would remove the need to do that. “In a way, it gives us certainty,” he said.

Seeing how complicated this could be, Piccini agreed to extend the deadline for these agreements from March 2023 to 2024, to factor for elections and drawn-out negotiations.

“I don’t want to rush decisions,” Piccini told The Narwhal. “We want municipalities to support them, to work with them, to make the most informed decision. So this gave everyone a runway.”

That runway, however, comes with a lot of uncertainty.

Critics still concerned about funding for Ontario conservation authorities

A lingering problem some see with these agreements is that they don’t guarantee funding in line with what conservation authorities need to face the climate emergency. In theory, municipalities can choose not to sign a funding agreement with a conservation authority. Basit said conservation authorities largely have good relationships with municipalities that just have to be codified on paper, others are less sure.

Victor Doyle, a former provincial planner credited as one of the architects of the Greenbelt, is concerned the new regulations don’t seriously acknowledge all the funding that conservation authorities need to provide the three categories of programs and services.

In the 1990s, the Mike Harris government cut provincial funding to conservation authorities from $50 million to $8 million per year divided amongst them. This led to conservation authorities having to reduce their staff between 20 and 60 per cent, according to the Canadian Institute for Environmental Law and Policy, and that funding has never been replenished. There has been no major new funding and no adjustment for inflation. Municipalities shoulder most of the costs while also benefiting from the revenue of development those authorities oversee.

“So there’s no certainty that conservation authorities will be funded to the level needed to operate in a meaningful way,” Doyle said. “These regulations seem to be part of this broader systemic weakening of the conservation authorities, brought about by the influence of the development sector on both the province and municipal politicians.”

Others skeptics mention the Ford government’s track record on environment issues, which include dismantling or watering down dozens of conservation and clean energy programs. The working group has asked but has not received clarity on the power of the minister to dismiss a conservation authority’s recommendation on development. The minister of natural resources did not respond to The Narwhal’s request for more information on this regulation. Piccini also didn’t provide a clear answer on this, noting only that conservation authorities “play an important role in supporting the local municipalities in their plans for growth.”

“No amount of regulation is going to overcome the fact that conservation authorities’ ability to use science and evidence-based decision-making to protect us from flooding and protect our drinking water has been completely undermined by this government,” Mike Schreiner, leader of the Ontario Greens, said.

But conservation authority heads say the lesson learned from the last 11 months with the working group is that meaningful engagement and collaboration works.

“What’s making us feel so much better about the future of conservation authorities is that we now have a partnership with the provincial government, which is what we always wanted,” Casgrain-Robertson said. “Our goal was never to be opposed to any sort of change. We were open to change. We just wanted to be able to work with the government to make sure that changes were done in a way that was responsible, and that would lead to us being able to do our work in a better way.”

“I’m hopeful that the regulations were written in a flexible enough manner that we’ll be able to adopt at a local level in a way that lets us continue to be effective watershed managers,” she said.

Basit notes the province is seeing greater climate challenges while its population is also increasing and its infrastructure ages. Many of the dams and flood control works that conservation authorities are responsible for were built in the 1950s. Meanwhile, natural hazards are only becoming more frequent and destructive — as seen in B.C. last week and in flooding in Ontario over the past few springs.

“I think it’s more important today than it ever has been in our history that we work closely together with all levels of government,,” Basit said. “I’m really hoping that now that the province has clarified the rules, we can actually start working towards those things.”