Water is precious — and precarious — on First Nations reserves like this one

Boil-water advisories in Moose Factory, Ont., are frequent, expensive and ongoing — but not ‘long-term’...

On a windless, warm fall day along the north shore of Lake Superior, a group of Lakehead University students were listening closely to their professor, until one of them broke down in tears. The professor, Robert Stewart, had been studying this area of Jackfish Bay, where Blackbird Creek pours into the greatest of the Great Lakes, since 2008. After all those years, he was used to the noxious mix of eggy sulphur and the steamy mist that stifles the air. But the students were getting queasy, so he paused his lecture.

Between the smell and the wine-stained plume on the shore of a lake known to be pristine, the weight of industry was bearing down. On that day, Blackbird Creek wasn’t as it sounds. It’s a lovely name for the effluent canal of a pulp mill.

In January 2024, the AV Terrace Bay pulp mill that had long pumped effluent through Blackbird Creek, en route to Lake Superior, closed. Just a few months later, Stewart along with Tim Hollinger, his former master’s student and now a remedial action plan coordinator, returned to the creek mouth and found the water teeming with oxygen — trout fry were jumping in the pools. Blackbird Creek was clear, cold and alive.

Stewart and Hollinger were back in October 2024, collecting samples from various sites, and stopped for a moment to relax in the sunshine at the creek’s mouth on Jackfish Bay to reminisce. Hollinger remembers the people he brought to the creek over the years from scientists to students, paddlers to government officials, recalling the horror on their faces upon viewing the hot, foamy sludge: “People didn’t think it was possible in this day and age in Canada.”

The weather was serene on that fall day. The plume that had left a brown slick across Jackfish Bay had all but disappeared into the iridescent turquoise the lake is famous for, and the noxious smell was replaced by the earthy notes of fall in northwestern Ontario. It had been nearly 10 months since the AV Terrace Bay Pulp Mill walked employees off site, shuttering the mill that first opened in 1947. The resilience of nature was overcoming an industrial legacy of nearly 70 years.

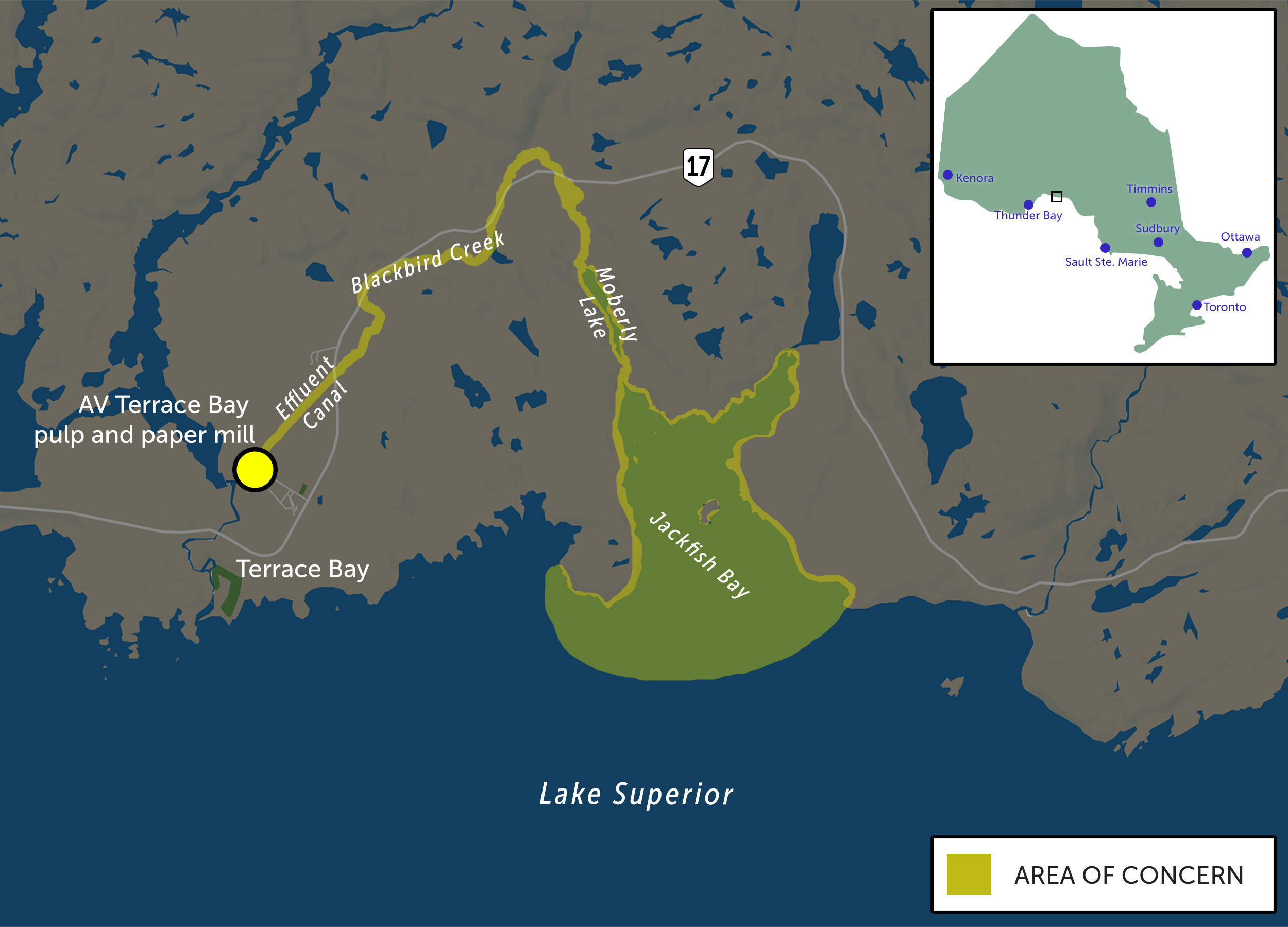

When the Terrace Bay pulp mill opened, an effluent canal was built to connect with Blackbird Creek — a convenient way to send its liquid waste into Lake Superior. It wasn’t until the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement was signed in 1972 that researchers started to focus on the impact industry was having on the Great Lakes. Following that agreement, in 1987 Jackfish Bay and 42 other sites across the Great Lakes in Canada and the U.S. were officially listed as areas of concern. New guidelines were created for discharging effluent into the Great Lakes and their tributaries, and remedial action plans were proposed.

But the use of Blackbird Creek as an effluent canal was grandfathered into the Terrace Bay mill’s operations. When it first opened, the mill owner was entitled to choose where to monitor the receiving environment for its effluent. They chose Moberly Bay, the smaller bay at the mouth of Blackbird Creek, on Jackfish Bay. That means Ontario’s Environment Ministry regulates the mill’s wastewater up to the end of the pipe that pours into Blackbird Creek, requiring that it’s cleaned to current effluent standards, while Environment and Climate Change Canada monitors the effluent’s impact on the environment in Moberly Bay.

The creek is caught in between and left unregulated, monitored only by researchers like Stewart and Hollinger — who are hoping someone else starts paying attention.

Creating pulp, a fibrous cardboard-like material, begins with logging trees. At the mill, the tree bark is removed and turned into hog fuel, a form of biomass that is used to help heat or power the mill itself. The barkless trees pass through a chipper. Those chips are put into a giant pressure-cooker-like machine called a digester, where the white liquors are added to break down the fibres. The remaining wood product is washed and bleached, pressed into sheets and shipped to manufacturers around North America — and sometimes overseas — to use in toilet paper, diapers and greeting cards. In short, pulp is the first stage of creating paper products, and effluent is what’s left behind.

Locals of Terrace Bay and nearby Schreiber, Ont., refer to Blackbird Creek as the “liquor line” because of the liquors used and produced through the pulp refining process.

At a mill 200 kilometres down the road in Thunder Bay, Ont., treated effluent is piped straight into the Kaministiquia River, which flows into Lake Superior. But instead of the wastewater hitting the river at surface level, as is the case with Blackbird Creek, this effluent pipe is 4.5 metres underwater, so the effluent cools instantly and disperses, where it’s less impactful. The much larger river can absorb the effluent with far fewer environmental impacts. It’s not perfect, but it is the best practice to satisfy a wood-fibre hungry market.

The reality is, if the Terrace Bay mill reopens, Blackbird Creek will likely die. If it doesn’t reopen, the town itself is in a tough spot.

With sideways rain and an easterly gale pounding on the Terrace Bay Community Centre walls, Marianne Whitton and Kim St. Louis are putting together a 1,000-piece puzzle and are stumped by the intricacies.

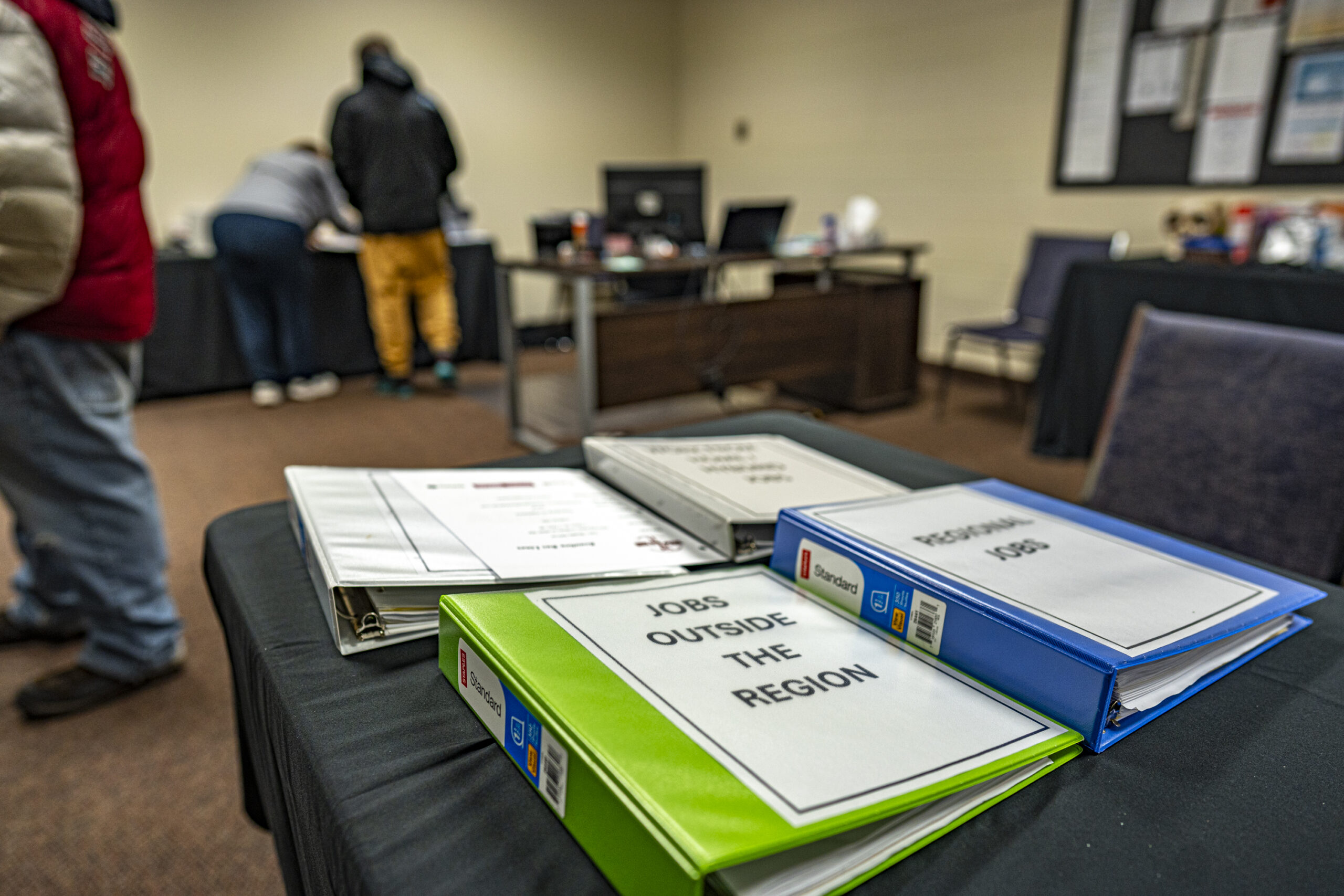

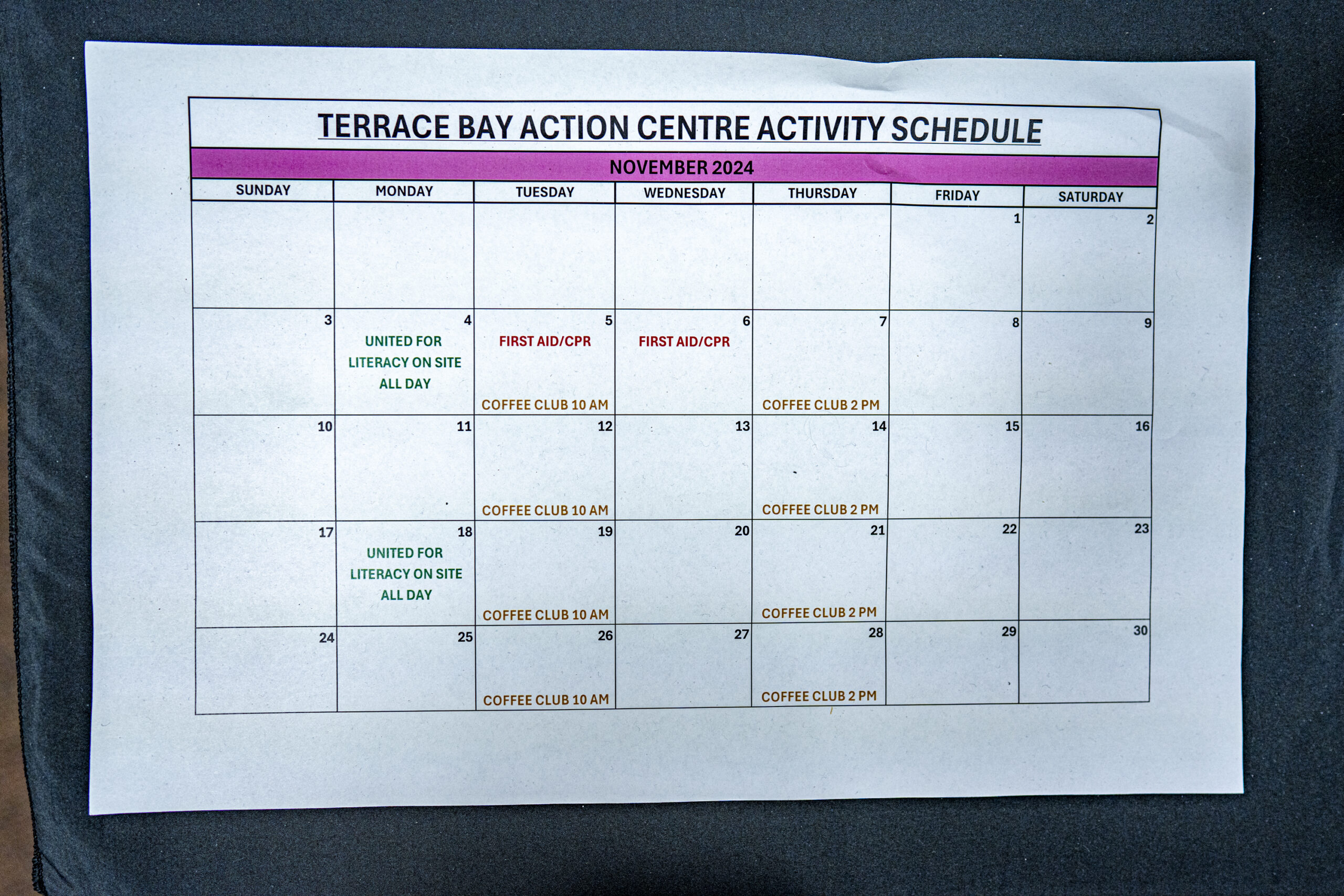

The two are helping run a $280,000 government-funded action centre to retool, train and help unemployed mill workers access jobs in and out of the region. Turnout has been low. Some skilled labourers were quick to snatch up available jobs, others were willing to collect employment insurance benefits and hope for the mill to reopen. As employment insurance nears its deadline for collection — just over 10 months in Ontario — former employees are starting to collect their severance pay from the mill, forfeiting their seniority and losing hope of finding employment in their hometown.

Rumours circulate about new investors — there’s a boiler being installed to keep the mill warm through the winter — but Aditya Birla Group, the India-based owner of the Terrace Bay mill, has offered no word to anyone, seemingly not even the township. The company did not respond to The Narwhal’s questions about plans to reopen or whether an alternate plan for discharging effluent would be in place if it did.

The few visitors to the action centre look at the puzzle and try to help. “This is 1,000 pieces of hell,” St. Louis says, finally standing up to take a break. She worked in pulp sales, finding a home for the town’s staple product in the broad North American market. “At least I’m getting paid to work on this puzzle, but I’d rather be at work selling pulp.” Others in the action centre nod their heads.

People who worked in the mill aren’t shy about its condition before it finally closed. They describe concrete falling from the ceilings, cracks in the floor and the lime kiln that was broken, creating a mountain of untreated lime they were hastily cleaning up.

In 2011, TJ Berthelot lost his life when a blow tank exploded, creating a nine-metre hole in the mill roof. AV Terrace Bay was fined $275,000 under the Occupational Health and Safety Act for the incident. Following a June 25, 2019, incident, the mill was fined $80,000 for not installing proper guards after a worker was pulled into the rollers that press the fibre sheets together. The worker was saved when another employee hit the emergency shutoff.

The mill has also seen its share of environmental infractions. In 2015, AV Terrace Bay was fined $250,000 for not properly treating effluent discharged via Blackbird Creek into Lake Superior. In December 2020, AV Terrace Bay was fined $400,000 for releasing high levels of sulphur. The emissions were detected by two air monitoring stations in the community.

The Jackfish Bay Area of Concern, which includes Blackbird Creek, was designated as “in recovery” in 2011. This recognized improvements made by the mill in the late 1980s and early 1990s, including installing a secondary treatment system for effluent and moving to chlorine-free pulp production.

Importantly, the mill was shuttered when the area was deemed “in recovery,” and the plan was to revisit the designation should it reopen. The mill did reopen three years later, but the designation remained.

The review committee, along with several government bodies, acknowledged in the remedial action plan status report that some of the area “may not recover while industrial effluent is discharged,” but concluded “further remedial actions are not practical or feasible at this time.”

What “in recovery” status means, practically, is that environmental monitoring will continue, but no interventions to help the environment are being explored or considered. And the designation could still be reviewed.

The mill will either reopen or it won’t, and the chips will fall where they may.

As nature continues to rebound, clean sediments will wash down Blackbird Creek and cap the contamination. And it would remain there if not for hundred-year storms, for floods, for beaver dams and the power of nature that upends even its own remedies.

Stewart and Hollinger will be back to monitor any shifts in the environment, and to introduce a new group of students to the history of sanctioned pollution in these waters, with its future still uncertain.

All that is known right now is in northwestern Ontario, an industry is dying, a town is suffering — and Blackbird Creek has a new lease on life.