The Right Honourable Mary Simon aims to be an Arctic fox

Canada’s first-ever Indigenous governor general doesn’t play favourites among our majestic natural wonders, but she...

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter.

êpihkonâkwâki waskôwa ispimihk ispî ê-mâmawêhticik ohci Montana First Nation ê-pôsicik nâway âwatâswâkanihk, ê-pimâpowicik ê-osâwâk paskwâw ê-wî-nitawi-kanawâpamâcik mihcêt paskwâwimostoswa.

Grey clouds loom overhead as a group from the Montana First Nation rides in the back of a pickup truck, sailing through a sea of prairie gold with their gaze fixated on a herd of Buffalo.

mitâtaht omâcîwak, kahkiyaw ê-pôsicik nâway ê-pihkonâkosit 2023 Dodge Ram Warlock, pêyâhtik ê-nawasônâcik kamâcîhk: ê-apisîsit moscosis ahpô êtikwe nân’taw ê-nîsopiponêt.

The 10 hunters, all packed in the bed of a grey 2023 Dodge Ram Warlock, carefully choose one to harvest: a small cow roughly two years old.

Treyvon Pipestem, oyahiwêw pâskisikêw, oyapahcikêw êkwa pâskisikêw nistam. mêtoni sêmâk, mihcêt pisiskiwak wâsakâmeskawewak kâ-paskisôt pisiskiw e-nâkateyimâcik pâmayes kawâyinohtecik kâ-apisâsik sakâhk.

Treyvon Pipestem, the designated shooter, aims and fires the first shot. Upon impact, the herd instinctively surrounds the injured animal to offer protection before retreating to a small wooded grove nearby.

omâcîwak pimitisahwêwak êkwa ayiwâk nistwâw pâskiswêwak isko ê-kawatahwâcik ana kâ-nawasôniht mostos. piyisk paskwâw mostos ê-pâhksinit, pisiskiwak ahtohtêwak. mihcêt kâ-wîcîwêcik, êkweyâc ê-mâcîcik, ê-kiskinohamâkêcik wâhkôtowin ohci ayisiyiniw êkwa paskwâw mostos.

The hunters follow and fire three more shots until they finally bring down the chosen cow. Once the Buffalo is down, the herd moves on. For many involved, this hunt was their first, serving as a tangible example of the relationship between humans and Buffalo.

“namoya ê-kiskeyihtamân tân’si kêspayik êwako ôma mâcîwin,” Kyra Northwest, ê-ohcît Montana First Nation itwêw. “mêtoni nipîkwêyihtamihikon. mihcêtwâw nimâton.”

“I wasn’t sure what to expect with the hunt,” Kyra Northwest, a member of Montana First Nation, said. “I was really emotional. I cried a bunch of times.”

nipêhtên ôma mâcîwin ê-mekwâpimâcihoyân Vancouver isi Montana, ê-natonikêhk kakwê-nisitohtamihk pêhcinâway êkwa mêkwâc tân’si ôki kêhcinâ paskwâwimostoswak paskwâhk êkwa tân’si mâmawinitowina ê-isi-atoskâtahkik kâwê-ka-pimâtisicik. êkwa ê-kî-nohtê-nâtonikêyân niya tipiyaw êkwa aniskac wahkômâkanak asci ôki kâ-sohkisicik wâwîpac ê-pawâtahkik.

I learned about this hunt while on a road trip from Vancouver to Montana, seeking to understand the past and present role of Buffalo on the plains and how communities are working to restore them. I also wanted to explore my own personal and ancestral connection to these lumbering giants who have often appeared in my dreams.

otipêyimisowak niwâhkômâkanak ê-kî-mâcîcik êkwa êkî-wîkicik ê-wâhkômâcik paskwâw mostoswa – êkwa nikiskiwêhên ê-kî-isinâkwâki paskwâwa mitâtahtomitanaw askiy pêhci-nâway ispî pêyakwâw kisipakihtâsowin iyikohk ê-kî-ayapohêcik nêtê ohci Alaska sakâwa isko pahkisimohtâhk maskotêwa Mexico, akâmi misiwêskamik ohci Banff isko sâkâstênohk Appalachian asinîwaciya. êkota ohci onêtawaskêwiyiniwak kekâc mêscihikwak, pahki ohcitaw ê-kakwê-nohtêkatêhihcik iyiniwak ohci paskwâw.

My Métis ancestors hunted and lived relationally with Buffalo, and I can envision how the prairies must have looked hundreds of years ago when millions roamed freely from Alaska’s boreal forests to the western grasslands of Mexico, across the continent from Banff to the eastern Appalachian Mountains. Then colonizers nearly wiped them out, part of a deliberate genocidal effort to starve the Indigenous nations of the plains.

anohc êkwa, asimê paskwâwimostoswak ê-wâpamihcik, mâka iyiniw mâmawinitowina ê-atoskâtahkik ka-pê-kîwêyit isi paskwâk, pâ-peyak ôhi pêyakoskânesiwina. ka-p̂e-kîwêtahihcik, otitêyihtamowin ê-kî-mâcipitahk Sto:lo omasinahikêw Lee Maracle, onahascikewin kâwe kamînonamihk askiya êkwa isihtwâwina, mistahi ê-iteyihtâkwâk ka-kistêyihtamihk pêhci-nâway êkwa anohc asci ôtê nîkânihk, êkwa ka-pimitisahamihk iyiniw wiyasiwêwin.

Now, there are far fewer Buffalo to be seen, but Indigenous communities are working to rematriate them to the grasslands. Rematriation, a concept advanced by the late Sto:lo author Lee Maracle, is the process of restoring lands and cultures, done with deep reverence to honour not only the past and present but also the future, and rooted in Indigenous law.

Montana First Nation ê-kî-mâcihk nâway ohpahowipîsimohk otaskîwâw Louis Bull Tribe. nânapô wîcihiwêwak anita newo pêyakoskânêsiwak ohci Maskwacîs, ê-ayâk apihtâkîsikanohk ohci amiskwâcîwâskahikanihk.

The hunt by Montana First Nation took place this past August on the lands of the Louis Bull Tribe. Both are part of the four nations of Maskwacîs, located south of Edmonton.

“nitêyihtên mâcîwin ohci pikwâwiyak kâ-wîcihiwêt kâkî-nistawêyihtam kêsi-wâhkohtocik kitayisînîminawak, askiy, êkwa kiwâhkômâkaninawak, paskwâw mostoswak,” Northwest itwêw.

“I think the hunt allows for everyone involved to reflect on the relationship between our Peoples, the land, and our relatives, the Buffalo,” Northwest said.

“mêtoni ê-môsihtâhk kêsi-wâhkohtocik iyikohk âskaw poko ka-kiskisomikawiyahk, ka-pimâcihtâyahk, êkwa kakistêyihtamahk. wâhkohtowin: itahkômiwêwin ahpô ê-wâhkohtohk. êkwa namoya tepiyâ kêsi-ayisînîwiyahk, mâka pokîkway kikâwînaw askiy kâ-miyikoyahk.”

“There is a deep interconnectedness that sometimes we need to be reminded of, revitalize, and honour. Wahkohtowin: kinship or being related to each other. And not just related as humans, but with everything that Mother Earth provides.”

kâ-pimâcihohk mêskanâhk, nistam ninakîwin anita Bow River Valley anita Banff National Park, ita kâ-nakiskawak Tasha Hubbard capasis ocikâstêsinowin Sleeping Buffalo Mountain.

On the road, I make my first stop in the Bow River Valley of Banff National Park, where I meet Tasha Hubbard under the shadow of Sleeping Buffalo Mountain.

kîspinatamâsowi-otahowêw nêhiyaw ocikâscêpayicikêw êkwa okiskinohamâkew ohci Peepeekisis First Nations mêtoni kwayask ê-atosket. nisihkâc opêhtâkosiwin kihcipîkiskwewin iyikohk owâhkômakana ê-ispihtêyimât.

The award-winning Cree filmmaker and academic from Peepeekisis Cree Nation holds a grounded energy. Her soft but unwavering voice is a testament to how much these relatives mean to her.

iskwêyâc ocikâscêpayîs, Singing Back the Buffalo, ka-mâmitonêyihtamihk nîkânihk ita ôki pisiskiwak kihtwâm ka-papâmâcihocik ê-kîsi-sîpinecik ka-mescihîcik. kinwês ohci ê-sihtoskâtahk paskwâwimostos tipahamâtowin, Hubbard asci kotakak ê-masinahikâsocik êkwa kotakak paskwâwimostos natotwestamâkewak, ê-kî-pimâcihocik isi askiya Blood Tribe anita Stand Off, Alta., ka-masinahikâtehk mitâtaht ka-tôtamihk tahtwâskiy Sep. 24 ispî.

Her latest film, Singing Back the Buffalo, imagines a future where these animals can again roam free after enduring a shared history of genocide. As a long-time supporter of the Buffalo Treaty, Hubbard, along with signatory members and other Buffalo advocates, travelled to the lands of the Blood Tribe in Stand Off, Alta., to mark the treaty’s tenth anniversary on Sep. 24.

paskwâwimostos tipahamâtowin, ê-kî-masinahikâtehk onohcîtowipîsimohk 2014 ayinânew pêyakoskânêsowina, ayâwak ayiwâk 50 ê-masinahahkik êkwa astêwa 11 masinahikanisa ê-ispahâkêyimocik mâmawikamâtowin, kihtwâm isihcikêwin, êkwa ka-mînosihtâhk ohci paskwâwimostosak kâ-itêticik. ôma pimitâskowi-tipahaskana ê-isihcikêcik kâwe paskwâwimostos ka-pakwâcisit, ayisk mêkwâc ê-itêyimihcik “tipênimâkan” osâm ohci pêhcinâway ê-kipahikâsot, itwewin namoya ê-nahiskahkik kâ-pe-isi-aniskac nakatamâkêcik.

The Buffalo Treaty, signed in September 2014 by eight nations, now has more than 50 signatories and includes 11 articles emphasizing co-operation, renewal and the restoration of Buffalo populations. This cross-border collaboration aims to return Buffalo to their rightful wild status, as they are currently considered “domestic” due to their historical confinement, a word that hardly suits their ancestral legacy.

paskwâwimostoswak namoya pisiskêyihtamwak tipahaskana, êkwa kêyâpic, itakona ê-sîtastêhki nîkinikêwina ê-nakânikocik kâ-pimâcihocik. tipahamâtowin pakosêyihtakwan kisci pimohcêskanâsa ita ka-kaskihowak paskwâwimostoswak ka-atohtêcik êkwa ka-papâmâcihocik, pêyakwan kêkâc wâwâskêsiwak, maskwak, âpisimôswak, êkwa môswak. ôhi pimohcêskanâsa pokô kâ-âpacihtâk pahpiyakwan isi ohci naspitamowin pîtos isi, ka-sihtoskamihk mêtoni kâmisâk ayâwin pâpîtos isi kâ-paskwâk, ka-manâcihtâhk isihtwâwin êkwa ahcahkowin ohci iyiniwak, êkwa kehcinâ kinwês ka-nâkateyimihcik paskwâwimostoswak ka-mihcêticik kanakinamihk ayiwâk osâmi micisowin êkwa âhkosiwin pimpayiki.

Buffalo don’t care about borders, and yet, there are rigid regulations in place that stop their movement. The treaty envisions ecological corridors that will allow Buffalo to migrate and roam freely, similar to elk, bears, deer and moose. These corridors are essential for maintaining genetic diversity, supporting the vast ecosystem dynamics of the plains, preserving cultural and spiritual connections for Indigenous peoples and ensuring the long-term viability of bison populations by preventing overgrazing and disease outbreaks.

mihcêt paskwâw mêskanawa astêwa anita pêyakwâw kâ-kî-pimiskanawêcik paskwâw mostoswak kâ-âcipicicik ê-natonahkik mîciwin, nipiy, êkwa kêsi-takahkêyihtahkwak ka-mîcisocik, ê-asinatahahkik omêskanâmiwâw mihcêt askiya ê-âhtohtêcik.

Many prairie highways follow the once well-worn paths of the Buffalo as they migrated with the seasons in search of food, water and favourable grazing conditions, tamping down their own roads over centuries of migration.

“kâ-iyinîwiyahk, kipimitisahwânawak. êkosi wîstawâw kimêskanâminaw. êkosi, wiyawâw meskanâsa. êkospî, itakona misimêskanawa. kâ-pimâcihoyan paskwâwa, kîspin âta ê-kiskeyihtaman ahpô namoya, ê-askôhaman paskwâwimostos opimohcêskanâsa,” Hubbard itwêw.

“As Indigenous people, we followed them. So they became our paths too. Then, they became trails. Then, they became highways. As you are moving across the prairies, whether you know it or not, you are following those Buffalo pathways,” Hubbard said.

tâpiskoc kipêyakohewâmak, paskwâwimostos tâwiskam mistahi kâ-ayimak mayitôtamowin, ohpimê kâyâk, êkwa pakwâtikosiwin, mêtoni iskwahêwin ê-misiwanâcihtâhk asci anihi ayâwinakâ-sihtoskahkik. kêkâc kâ-mêscihihcik paskwâwimostoswak ê-kî-ispayik mihcêt kîkwaya ohci, asci konta wiyanihtakêhk ka-paskwatahikehk ohci manâcihcikêwin ekwa kistikewin, êkwa osâmi konta mâcîwin êkwa kameskotônikêhk pahkêkin.

Much like our families, Buffalo faced severe violence, displacement and discrimination, which had devastating effects on their populations and the ecosystems they supported. The near-extermination of Buffalo was driven by a combination of factors, including reckless slaughter to clear land for economic and agricultural development, as well as excessive hunting for sport and the hide trade.

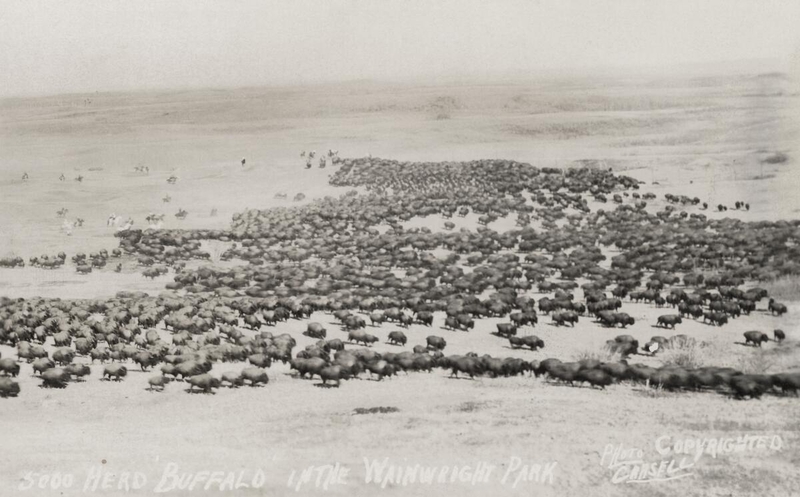

nîswâw mitâtahtomitanaw askiya, North America ê-kî-wîkicik nân’taw 30 isko 60 pêyakwâw kisipakihtâsowin paskwâwimostoswak. anohc, kâ-itêhticik astamihk, têpiyâ 2,200 paskwâwimostoswak ê-ayâcik êkwa nân’taw 10,000 sakâwimostos ê-itakocik pakwacâyik ahpô ê-kanawêyimikâsocik misiwihtê “kanâta.” mêtoni kêsi-mihcêticik ohci kâ-okimâwihtâkosicik êkwa ê-ohpikihihcik: ispî ohci 2021, kekâc 150,000 paskwâwimostoswak ê-kî-miskawihcik kanâta kistikâna.

Two centuries ago, North America was home to an estimated 30 million to 60 million Buffalo. Today, the population has significantly decreased, with only about 2,200 Plains Buffalo and around 10,000 Wood Buffalo remaining in the wild or protected areas across “Canada.” The vast majority of these majestic creatures are now livestock: as of 2021, nearly 150,000 Buffalo were found on Canadian farms.

paskwâwimostos ka-pimâcihihcik mêtoni mistahi ka-tôtamihk kîkway,” Hubbard itwêw.

“Buffalo restoration is a huge undertaking,” Hubbard said.

“piko ka-nîsokamâtohk. êkwa ê-mâmawaci-ispihtêyihtakwak iyiniwak namoya nâway kâhîcik kiyânaw ka-wîcihiweyahk kâ-wî-itasiwêhk kîkway, wâwîs kêhcinâ ayâwina. ka-kiskisihk poko ana iyiniw-nîkânîwin atoskâtamowin.”

“It’s going to take collaboration. The most important thing is that Indigenous people aren’t just afterthoughts — that we’re part of that decision-making body, especially when it comes to certain places. Remembering that it needs to be an Indigenous-led effort.”

ê-mêkwâ-itohteyân amiskwacîwâskahikanihk, nit-ati-nakîn Elk Island kanakiskawakik paskwâwimostoswak. kâpahkisimohk ê-wâsihkopayit p̂eyak tipahikan misiwê askîhk. nimiyopayihikon: paskwâwimostoswak pikwihtê ayâwak. niwâpamâwak ê-tihtipîcik askîwiwaskonâkwak asiskiy ita kâ-tihtipîcik, mostoswak êkwa moscosisak e-mîcisocik, êkwa iyikohk kâ-itikiticik âh-ayîtaw kâ-nanawiyaw-nakîcik ê-pe-wâpamâcik ôhi.

On my way to Edmonton, I make a pit stop at Elk Island to meet the Buffalo. The setting sun casts its golden hour glow over the land. I get lucky: Buffalo are everywhere. I see them wallowing in shimmering dust clouds from their dirt baths, cows grazing with their calves, and their impossible size juxtaposed unnaturally close to the lineup of vehicles also visiting.

paskwâwimostoswak ê-metawêskicik, ê-pâmi-pimipahtâcik êkwa ê-nawaswâtocik, ê-ostikwânahikêcik êkwa ê-nôtinitocik, ê-tihtipihcik êkwa misipotacikêcik. ê-pimohtêhocik ê-isi-pêyakohêmicik, êwako ê-kî-wâpahtamân ê-papamohtêcik askiya pâmayês niya. mwêci, kihci-kanaweyicikêw ê-nîkânohtahât pisiskiwa ek̂wa pônîwak nâway ê-kisâtahkik, ê-osâpicik.

Buffalo are playful, running around and chasing one another, headbutting and sparring, bellowing and snorting. They travel together in family structures, which I witness as they wander the land before me. Typically, a matriarch leads the herd while the bulls linger behind, keeping a lookout.

tahtwâw kâ-tâkiskiyân nitohpwê̂piskawâwak kwâskohcisîsak pâmwayês kâ-pimpayiciket ponî ê-kanawâpamitoyâhk. mêtoni êwako kêhcinâ ê-mâmawi-misikitit pisiskiw ê-tâwiskawak — paskwâwimostos ê-mâmawi-misikitit pisiskiw North America, ê-kisikwatit 900 kg ekwa ê-nîpawit isko nîso metres. ê-âyakaskisit kwayask ê-itâpit oskîsikwa êkwa omîstiwanihk mihcêt êkota pakitinikanak.

Every step I take stirs up clouds of grasshoppers before a dominant bull and I lock eyes. He must have been the biggest animal I’ve ever encountered — Buffalo is the largest mammal in North America, weighing up to 900 kilograms and standing almost two metres high. He is broad with expressive eyes and a beard filled with seeds.

êkosi miyosiwak ê-papâmi-pakitinâcik pakitinikanak osâm ayisk ê-akopayit owayânihk ahpô omiyêstawânihk ê-papâmipicik ita kâwîkicik. ispî paskwâwimostoswak ê-sinkonisocik mîtosihk, nîpisîwahtikok, ahpô kotak waskicâyik, pakitinikanak akopayiwak owayâniwâw êkwa kamêskot-itotahêwak oskayi ayâwina.

This makes them excellent at dispersing seeds, which cling to their fur or beards as they move through their habitats. When Buffalo rub against trees, shrubs, or other surfaces, seeds stuck in their fur can be transferred to new locations.

kâkwâtikihihcik itowa, mêtoni ê-kî-ispihtêyihtâkosick ka-mînonahkik askiya. namoya têpiya kâmîcisocik ka-mînonahkik askiy êkâ ka-misi-itakoki nîpisêwâhtikos êkwa maskosiya, mâka mostosomey ohci ka-miyo-ohpikik anita asiskiy êkwa kwasyask kêtakohk kistikêwin. ôhi maskosiya itakona ka-mîcihk êkwa ka-tâkoskâtamihk ohci pisiskiwak, ekwa kâ-miywâsik maskosiy ohci kâ-wî-miywâsiki paskwâwa — piko kîkway ê-mamisîtotamihk anima maskosiy, kahkiyaw pisiskiwak êkota paskwâw kâ-môwith.

As a keystone species, they have played a significant role in shaping these lands. Not only do their grazing patterns help maintain the grassland ecosystem by preventing the encroachment of shrubs and trees, but their dung fertilizes the soil and supports a diversity of plant life. These grasses have evolved to be grazed and trampled on by herds passing by, and the health of the grass dictates the health of the prairies — everything depends on that grass, all the animals in the prairie food chain.

kotak kîsikâw, kâpê-nakiskawak Kyra Northwest, namoya kîwâpamâwak paskwâwimostoswak, êkwa apsis kaskâpahtêw ê-pastêhk cîki Wood Buffalo êkota ayâw. Northwest, asci Hubbard, ê-kî-mâcipitahkik International Buffalo Relations Institute (IBRI). ôma mâmawinitowin ê-ahkamêyihtahkik ka-sipwepitahkik paskwâwimostos tipahamâtowin êkwa ka-sihtoskawâcik iyiniwa kâwê-kakîwetahâcik paskwâwimostoswa otaskîwâw.

The morning after the hunt, when I return to meet with Kyra Northwest, the Buffalo are nowhere to be seen, and a dense veil of smoke from a fire near Wood Buffalo has settled over the area. Northwest, along with Hubbard, is a founding member of the International Buffalo Relations Institute (IBRI). This organization is dedicated to promoting the Buffalo Treaty and supporting Indigenous nations in reintroducing Buffalo to their lands.

kapêsiwin mîcisowinâhtik cîki anita Astotin Lake, Northwest itwêw namoya mihcêtwâw tâwipayin ka-wâpamihcik paskwâwimostoswak ê-ohpikicik. kêsi-kiskeyimât têpiyâ ispî kâ-kiyoket ita pisiskiwak kâ-kanaweyimihcik êkwa kanawê-mostosowêwin êkwa kêskaw ê-miskwâpamât kâ-mêkwâpimpayit.

At a picnic table near Astotin Lake, Northwest said she didn’t have many opportunities to see Buffalo growing up. Her experiences were limited to occasional visits to zoos and ranches and brief glimpses during drives.

“nohkom kî-âtotam iyikohk ê-wâhkômât,” Northwest itwew. “ê-kî-itwet ê-wâhkômakik paskwâwimostoswak osâm niya, niya, ê-kî-otinikawiyân ohci nitaskiy. ê-kî-ahikawiyan ê-menkanihkâtêhk ayâwin. ê-kî-otinikawiyân ohci nipêyakohêwamak.

“My kokum talked so much about how she relates to them,” Northwest shared. “She said, ‘I relate to these Buffalo because I, myself, have been taken from my land. I was put in a fenced area. I was taken away from my family.’

“kakwâtakêyimowin iyikohk ê-pîkonamihk kêsi-wahkomiht paskwâwimostos osâm âspis ka-wâpamihcik nântaw askiy. nitêyihten wêhtinâ ati-mêskocipayin êkwa pîtos ispayin ohci pêyakoskânêsiwak kâwê ê-pê-kîwêcik paskwâwimostoswak omâmawinitowiniwâw êkwa kâwe otaskîwâw.

“It’s sad that there’s this big disconnect to Buffalo because it’s so rare to see them anywhere on the landscape. I think that’s slowly changing and shifting with nations bringing Buffalo back into their communities and onto their lands.”

Northwest itwêw pêyak mistahi kîkway êkiskinohamâkosit “tân’mayikohk aniski-wâhkohtowin êkwa pimâcihtâwin kâtoskâtamak.”

Northwest said one of the biggest things she’s learned is “how much reconnecting and revitalization we need to do.”

“nititêyihten mistahi kikiskinohamâkosiwina, kîkwaya kâ-kiskinohamâkosiyahk isihcikêwinihk, êkwa kîkwaya kâ-kiskinohamâkawiyahk ohci peyakohêwamak êkote anima ê-ohcipayik,” itwêw. “ê-mâmitonêyihtamihk tân’si ê-isi-nâkatôkâtitocik. ê-mâmitonêyimihcik kihci kanawêyicikewak êkwa tân’siyisi, iyikohk namoya kîkway wâhkohtowin, namoya kikîwâpamânawak askiy mêtoni kinwês, mêtoni kwêtawêyimâwak.

“I think a lot of our teachings, things that we learn in ceremony and things that we learn about as families come from them,” she said. “Thinking about how they take care of each other. Thinking about their matriarchs and how, with that physical disconnection, we haven’t been able to witness their presence on the landscape in a long time, it has been missed so much.”

Banff National Park peyak ewako kikiskinohamâkonaw tân’si ôma pakwaciwin kâ-isinâkwan. ispî 2020, Northwest, Hubbard, êkwa pêyakwâyak kî-pimohtêwak ka-wâpamâcik paskwâwimostoswa.

Banff National Park is one prime example of how this rewilding can look. In 2020, Northwest, Hubbard and their team hiked to see the Buffalo.

“nikiskêyihtênân paskwâwimostoswak ôta ê-ayâcik. nikiskêyihtênân êkota ê-ocawâsimisicik, êkwa ê-tipêyimisocik êkwa pikwihtê ê-papamohtêcik. âskaw nititohtân ayâwina ita kâ-itêyihtaman namoya ka-wâpamacik mostoswak, êkwa êkota êkwa ayâwak mostoswak, êkwa tâhtwâw kâ-wâpamakik, niteyihten: pêyak kîsikâw kahkiyaw ka-itakonâwâw paskwâwimostoswak,” itwêw.

“We know that the Buffalo are there. We know that they’re having their babies there, and they’re free and roaming everywhere. Sometimes I go to places where you think that you wouldn’t see cattle, and then there’s cattle out there, and every time I see them, I think: one day you’ll all be Buffalo,” she said.

mihcêt pêyakoskânêsiwak atoskâtamwak kâwê kapê-kîwêtahihcik paskwâwimostoswak, êkwa mâci-wâpamêwak ê-itakoyit oskihtêpak. Northwest itwêw âtiht kêht̂e-ayak ohci Kainai First Nation wâpamêwak piyesîsa ê-pê-wayanîyit namoya wihkâc ê-wâpamâcik otaskîwâw. osâm paskwâwimostoswak ê-kanawêyihtahkik askiy êkwa mihcêt kotakak pisiskiwa, kâpê-wâyanîcik nawât êwako ka-wanipayik kîkway. pê-kîwemakan askiy, êkwa pê-kîwemakana nikamowina, isihcikewina, êkwa kâki-isi-itakoki paskwâwa.

As many Nations work toward rematriation, they are even starting to see plants return. Northwest said that some elders in Kainai Nation have seen birds returning that they’ve never seen on their land. Because Buffalo support the land and many other animals, their return has been compared to a missing puzzle piece. It brings back the land, but it also brings back the songs, the ceremonies and the way the prairies are supposed to be.

ka-pimipayi paskwâw anita Alberta êkwa Saskatchewan, êwako ê-isi-kiskeyihtamân paskwâwimostos mêskanaw, kêsi-wâpahcikâtêhk isi askiy ka-wâhkohtamihk. kâ-kitocik êkwa kâ-wâsaskotêpayik wâhyawês — ôhi paskwâw mâyikîsikâwa ispayinwa ohpahowipîsimohk ê-osâmi-kistêhk êkwa ka-miyimawâk ispî kâ-nîpik — paskwâw maskosiy isimâkwan askiy êkwa e-kanâcimâkwak.

Driving across the prairies in Alberta and Saskatchewan, along what I’ve come to think of as the Buffalo road, offers a view of the landscape’s interconnectedness. With thunder and lightning in the distance — these prairie storms often occur in August due to the intense heat and humidity that build up during the summer — the smell of prairie grass was earthy and clean.

Melissa Arcand, asiskiy biogeochemist êkwa ê-ohcît ohci Muskeg Lake Cree Nation, ê-nohtê-miywanahk ka-miyopayik ka-wâhkohtocik iyiniwak êkwa askiy ka-nistawêyihtahkik pêhci-nâway awahkânihkêwin êkwa ka-atoskâtamihk miyowihcêhtowin êkwa askiy ta-nâkatêyihtamihk. ê-wî-wît-atoskemât Hubbard ohci ka-kîwêcik paskwâwimostoswak, kânîsohkamawâcik iyiniw okiskinohamâkana.

Melissa Arcand, a soil biogeochemist and a member of Muskeg Lake Cree Nation, is interested in improving the relationship between Indigenous people and the soil by acknowledging historical exploitation and working toward reciprocal land stewardship. She is collaborating with Hubbard on Buffalo rematriation efforts, contributing to a network of Indigenous scholarship.

“nipakosêyimowon, ôta kâ-wîtatoskêmakik [International Buffalo Relations Institure) êkwa nitawâcîcikêwak, mahti kîspin atoskêwin kâ-itôtamahk ohci paskwâwimostoswak ê-miyopahikocik mâmawinitowina kâ-kakwê pe-kîwêtahahcik, ahpô kâ-kakwê-minopitahkik otaskîwâw,” itwêw.

“My hope, at least with working with [International Buffalo Relations Institute] and the research network, is to see if any research that we do with Buffalo is actually serving the communities who are trying to rematriate them, or who are trying to do restoration of their lands,” she explained.

kiyâm âta ita paskwâwimostoswak ê-namatakocik ayiwâk mitâtahtomitanaw mînâpihtaw, askiy kêyâpic kanawêyihtamwak wiyawâw kêsinistawêyimihcik, ê-ayâmakahk askîhk êkwa manicôsak.

Even in areas where Buffalo have been absent for a century and a half, the land still retains their legacy, embedded into the soil’s organic matter and microorganisms.

“kîkwây ê-mâmawi-miywâsik asiskiya, kiyâm âta ê-pîkonamihk, kêyâm ê-kîmwêstâcihkamihk êka ê-meskocipayik ohci kistikêwin, kêyâpic mistahi ê-nistawêyihtakwak 10,000 askiya, namoya têpiyâ nâway 100 askiya ahpô 2- askiya,” Arcand itwêw.

“What’s really cool is that our soils, even if they’ve been disturbed, even if they’ve been influenced and altered by agriculture, they still carry a lot of the legacy of 10,000 years, not just the last 100 years, or ten years or 20 years,” Arcand said.

“nipaskwâw asiskiya anihi ita ka-kanawêyimihcik paskwâwimostoswak ayisk ê-osihcikêmakahkik ohci kâ-mîcisocik, ita maskosiya êkota kâstehki, ohci omêyiwâw.”

“Our prairie soils are actually made to house bison because they helped develop them through their grazing, through the grasses that are there, through the defecation.”

âcimowin ohci paskwâwimostoswak kâ-mihcêticik National Bison Range anita Montana, kaskitew ayasit, ê-ohcîmakahk anita ohci paskwâwimostos tipahamâtowin êkwa ê-misâk âcimowin ohci iyiniw kanawêyicikêw. ôki pisiskiwak ohci apsis ê-itakocik opaspîwak ohci “Great Slaughter.” êkosi itastêw pêyakwâyak ayisiyiniwak ?Atatic’e?, okosisa Peregrine Falcon Robe, ê-kiskêyimiht isi Little Falcon Robe, ê-kî-atâwêt kîwâci moscosisak isi Flathead Reservation. pîyisk kâkî-wanihtâcik otaskîwâw, poko ka-atâwâkecik mostoswa. kanâta kihcio-okimânâhk poko kâ-nohtê-atâwêyit.

The story of the Buffalo herd at the National Bison Range in Montana, in Blackfoot territory, is deeply intertwined with the Buffalo Treaty and the broader context of Indigenous stewardship. These animals descend from a small number of survivors of the “Great Slaughter.” According to tribal oral history, ?Atatic’e?, the son of Peregrine Falcon Robe, known as Little Falcon Robe, brought the orphaned calves to the Flathead Reservation. When they eventually lost their land, they had no choice but to sell the herd. The Canadian government was the only willing buyer.

mitanaw askiya, peyakoskânêsiwak asci National Bison Range kî-nôtinitowak kâwe-ka-miyicik askiya êkwa ka-paminâcik paskwâwimostoswa. okocîniwâw kî-tâpwêtawâwak kisepîsimohk pêyak ê-akimiht, 2022, kâwe askiy ê-mîyicik.

For decades, the nations involved with the National Bison Range have tirelessly fought to have their land returned and to resume stewardship of the Buffalo. Their efforts were realized in 2022, when the land was officially restored to them.

Leroy Little Bear ana kaskitew ayâsit okihci-kiskinohamakew metoni ewîcihitâsot kâ-osihtâhk êkwa kâ-âhkamêyihtahk kâpacihtahk paskwâwimostos tipahamâtowin. mamahtawi-apacihcikanihk, ê-kikiskahk pakiwayân ê-masinipayit paskwâwimostowa — ispî Hubbard êkwa Northwest ê-mekwâ-pîkiskwâtocik — Little Bear niwihtamâk anima tipahamâtowin ê-ohcîmakahk ohci mihcêt pîkiskwatitowina ohci iyiniw nîkânîwak êkwa mâmawinitowina.

Leroy Little Bear is a Blackfoot scholar who has been instrumental in the creation and implementation of the Buffalo Treaty. Over Zoom, wearing a T-shirt with a Buffalo on it — just as Hubbard and Northwest did during our conversations — Little Bear tells me that the treaty emerged from extensive conversations among Indigenous leaders and communities.

“wâpamik oskayak, pêhtamwak âcimowina, pêhtamwak nikamowina, wîcihiwêwak isihtwâwina. mâka kâpaspâpiyan wâsênamawinihk, namoya kîkway kawâpamâwak paskwâw mostoswak,” Little Bear itwêw.

“See our youth, they hear the stories, they hear the songs, they participate in the ceremonies. But when you look out the window, there’s no Buffalo to be seen,” Little Bear said.

kâ-kakwêcimikawiyân tân’si ê-itamahcihoyân ka-ayâwakik Blackfoot pisiskiwak, Little Bear itwêw, “tâpiskoc niwâhkômâkanak ê-pê-kîwecik.”

When asked about how it feels to have a Blackfoot herd, Little Bear said, “It’s kind of like my relatives coming home.”

“ninitawikiyokawâwak. nêtê paskeskanâhk. ekota wiyawâw otaskîwâw. epapâmâcihocik pikwihtê. êkote nititohtânân ê-nitawi-nikamostamawâyahkik. âskaw, nipehtâkonânak êkwa pê-itohtêwak. ayiwâk ayisiyiniwak kâ-kiskeyimâcik paskwâwimostos, miywâsin.”

“I go and visit them. They’re just right off the road. They claim that territory. They roam around over there. We go over there and sing to them. Sometimes, they hear us and come towards [us]. The more people that know about Buffalo, the better.”

ê-pasikoyân êkwa ê-itâpiyân anita apahkwâtew ohci awa nikaskitewi Bronco ê-pimohtahoyân., nikanawâpamâwak mihcêt pisiskiwak ê-papâmi-mîcisocik anita tîtipîw ispatinâwa National Bison Range. wêhtinâ ê-waskawîcik mâka ohcitaw, âskaw ê-nakîcik ka-micisocik êkwa pasakoscêskawêcik. metoni nimiyomahcihon ê-kanawâpamakik pîhawawâskêwêyâk, êkosi ayisk anima kakî-ispayik.

As I stood up and peeked through the moonroof of the black Bronco I was travelling in, I watched the herd slowly graze across the rolling hills of the National Bison Range. They moved slowly but deliberately, often stopping to graze and wallow. It felt healing to watch them in an open space, as they were meant to be.

nimâmitonêyihtên tânimatahto kiyânaw kikaskeyihtamêyihtênaw ka-nakatamahk mamâtawi-apacihcikan pimâtisiwina êkwa kâwê kawâhkohtamahk askiy êkwa ahcahkowi kitimâtâsowin kâki-itôtamihk. paskwâwimostoswak maskihkîwiwahk. kikiskinohtahikonawak êkwa kikiskinohamâkonawak tân’si kêsi-pimâtisihk.

I thought about how many of us yearn to escape from our technology-driven lives and reconnect with the land after the spiritual trauma caused by colonization. Buffalo are medicine. They guide us and offer direction on how to live.

“nititeyihtên paskwâwimostoswak ê-sîpêyihtahk kinwês isko ayisiyiniwak ê-miskwêyihtahkik kîkway ka-itôtahkik,” Hubbard niwîhtamâk. “nitêyihtên ê-takohtêyahk ita êswêpayik ita ê-apâhkawâyâcik.”

“I think Buffalo has been patient for a long time while the humans catch up to what needed to get done,” Hubbard told me. “I think that we’re in a time where they are really permeating consciousness.”

ê-mêkwâ-pimipayiyân mêskanawa êkwa akâmi-tipahâskâna, ê-kîwâtahk askiy êkwa misiwihtê ôtênawa, ninitawâpênên askiy kîspin kîkway ka-itakot paskwâwimostos. namoya nânapô nân’taw êkwa pikwihtê, kâkî-itakocik astêyiwa kayâs itwahikana, mêskanâsa ê-isiyihkâtêhki, êkwa âcimowina ê-kî-pêhtamân Banff isko Missoula. micwêmwaci masinahikâtêhk pahki kipêyakoskânêsiwin pêhci nâway ê-masinahikâtêhk, êkwa nîkân asci.

As I drove across highways and interstates, through the desolate country and scattered cities, I scanned the landscape for any trace of Buffalo. They were both nowhere and everywhere, their presence woven into old signs, street names and the stories I heard from Banff to Missoula. An indelible part of our nations’ histories, and our futures too.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. A $335 million funding commitment to fund...

Continue reading

Canada’s first-ever Indigenous governor general doesn’t play favourites among our majestic natural wonders, but she...

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

A trade war could help remake B.C.’s food system, but will family farmers be left...