In a Nova Scotia research lab, the last hope for an ancient fish species

Racing against time, dwindling habitat and warming waters, scientists are trying to give this little-known...

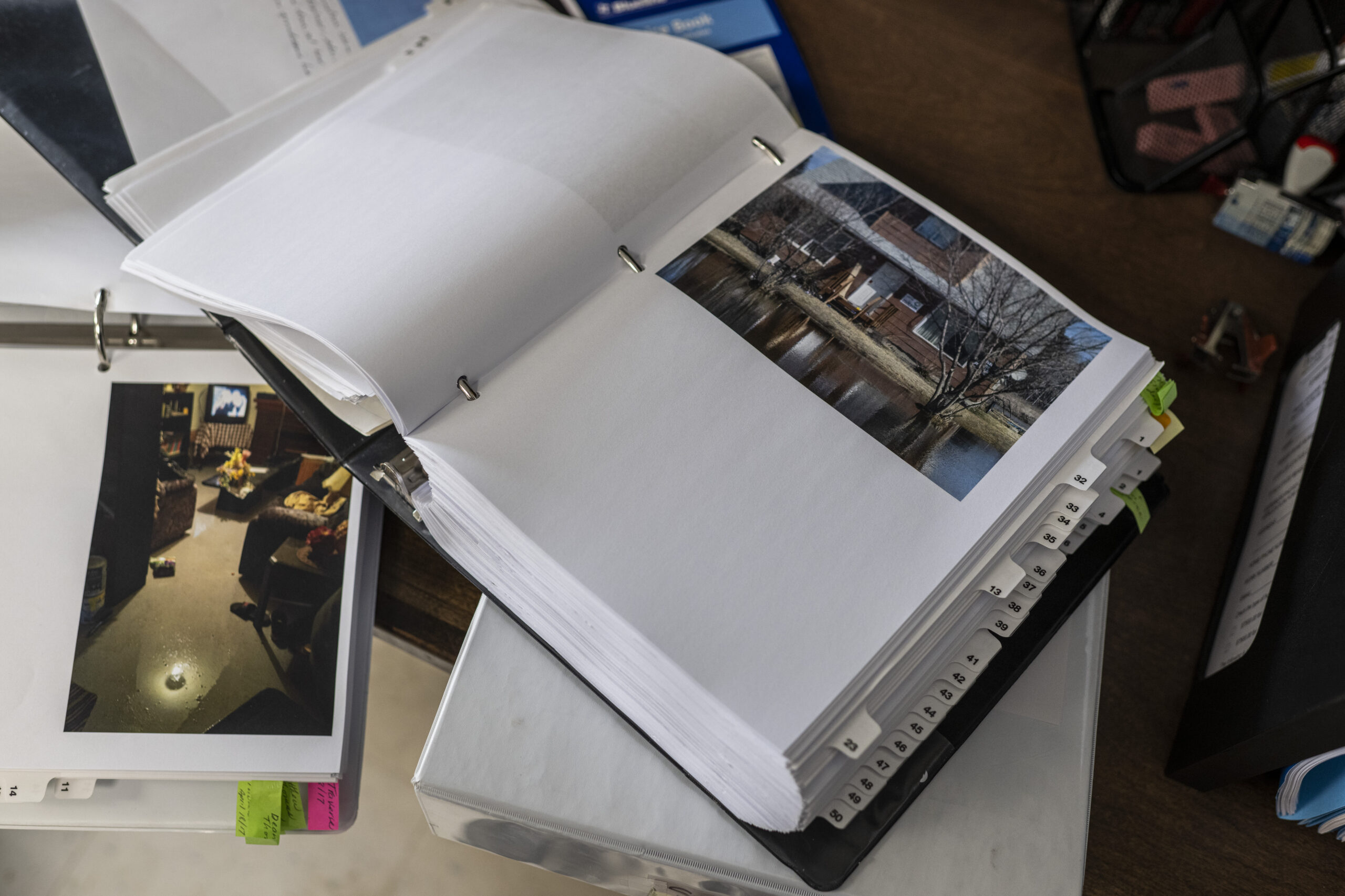

A year after a historic flood ravaged Peguis First Nation, there’s hope on the horizon.

The spring thaw passed without incident this year — a much needed respite for the still-recovering community — and a new, multi-government collaboration is giving Peguis a voice in how future floods are managed.

The 2022 flood was the most devastating in the First Nation’s embattled history, and the community’s leadership have long maintained the worst of the damages could have been avoided — if only governments had been listening.

Over the last two decades, Peguis has faced five major floods, prompting widespread evacuations, destroying infrastructure, hundreds of homes and displacing thousands of community members. Year after year, the Nation has urged provincial and federal governments to step in and help fund infrastructure projects to keep the community safe, come hell or high water. Year after year, they’ve been denied.

But as the anniversary of last year’s flood-peak passed this month, Peguis First Nation housing and emergency management director William Sutherland is optimistic.

“I’m a happy man,” Sutherland says on a phone call. “We are working on a permanent solution to bring everybody home, which is great news.”

More than 2,100 people were evacuated from Peguis First Nation when the community was overcome by flooding in spring 2022. More than 600 of those evacuees still haven’t returned.

The floods caused an estimated $300 million in damages, including the devastation of more than 300 homes, many of which were written off owing to mould.

Last year’s flood was one disaster too many for a First Nation that has spent decades in recovery mode. Repeated disasters have contributed to a severe housing crisis that has left evacuees stranded in hotel rooms and apartments across the province for years.

Some evacuees have been away from home for over a decade, relying on inconsistent Red Cross and income assistance funding to pay the bills. Those in hotels have been forced to shuffle from place to place on short notice as hotels run out of room. They’ve been separated from their families, children haven’t been able to attend school and the stress of displacement has caused anguish that only deepens as the evacuations drag on.

“Due to chronic underfunding of infrastructure, including flood prevention measures by governments, flooding episodes never end for Peguis,” former Peguis Chief Glenn Hudson wrote in a 2022 press release.

“Most of the houses are never re-built as a result of underfunding, and so many members can never come back to live in their community among their people. That is why I call these members ‘refugees,’ not evacuees.”

For years, Hudson and other community leaders had been pressuring the federal and provincial governments to help the First Nation develop long-term and permanent flood mitigation solutions, to no avail.

In the aftermath of the 2022 flood, a new partnership between Peguis, nearby Fisher River Cree Nation, local municipalities, the provincial government and Indigenous Services Canada (which administers emergency response services) has emerged, Sutherland says.

“Efforts are being made to put Peguis in a more proactive and flood mitigated position moving forward, that way we hopefully never have to have a partial or full evacuation ever again,” he says.

The effects of that partnership are already being felt. Last year’s crisis was exacerbated by the fact Peguis was denied federal funding to start emergency preparations in the spring because provincial forecasts predicted a low risk of flooding on the Fisher River.

“If we don’t qualify for funding and weather systems do impact our area, the most advanced warning that we get is 24 to 48 hours,” Sutherland says. “There’s nothing that can be done in that short period of time.”

Meeting notes between Indigenous Services Canada and Peguis leadership, obtained through a freedom of information request, showed councillors were incensed they had been denied the chance to prepare for the impending threat.

“Why can’t we be at the table when you make decisions? We would have told you what would happen,” one band councillor said during a May 4, 2022, meeting. “Someone needs to be held responsible.”

But this year, Sutherland says the partnership allowed Peguis an opportunity to show the province how the region’s unique geography puts the First Nation at an increased risk of flooding — even when predicted weather patterns and water levels indicate a lower risk.

Manitoba’s transportation and infrastructure department is currently working on new flood-risk maps for the Fisher River through a cost-sharing agreement with the federal government, an unnamed provincial spokesperson said in an emailed statement.

“The flooding that occurred in 2022 has reinforced the need … to identify and move forward with flood mitigation solutions,” the spokesperson said.

Sutherland presented evidence showing drainage systems on farmland south of the First Nation had been altered, prompting increased strain on the Fisher River watershed; he was also able to show how extreme rainfall caused a ridge north of the community to breach, leading to flooding from all sides.

The result was a more accurate flood forecast in 2023, which allowed the community to secure $2.5 million in preparatory funding.

“That put us in a more proactive position,” Sutherland says. “We utilized sandbagging and trucks and trailers, and were able to at least protect the most flood-prone homes.”

After the magnitude of last year’s flood, Peguis’ leadership ramped up a decades-long pressure campaign to get long-term flood mitigation commitments from provincial and federal governments.

During meetings at the height of the flooding, then-Chief Hudson expressed the stress, frustration and anguish experienced by his community, according to the meeting notes obtained.

“We’re sick of it,” Hudson told federal officials while asking to discuss long-term mitigation options at a May 3 meeting.

A month later, as cleanup operations begun in Peguis, Hudson stressed he “did not want any more studies” and would take guidance from the plans outlined after floods a decade earlier, which showed a need for new culverts and drainage, better roads, controlled water flow and upgrades to the local water-treatment plan.

Indigenous Services seemed to take heed: though they noted “this path for long-term mitigation will take years,” the department committed to working toward the community’s immediate and long-term needs. Indigenous Services recommended both a working group between local, provincial and federal leaders and a written agreement to guide the development of solutions.

Peguis’ cries for help were further bolstered in the fall when a November 2022 auditor general report found Indigenous Services had failed to provide adequate emergency management supports to First Nations across the country, citing a lack of regional emergency plans, a failure to identify high-risk communities, a sizeable backlog of underfunded disaster mitigation infrastructure projects and inconsistent supports for evacuees, particularly those facing long-term evacuations.

Many of these gaps had been identified in a 2013 auditor general report of emergency management in First Nations but had not been addressed, the 2022 report said. With environmental disasters like floods becoming increasingly severe and frequent because of climate change, the report said, First Nations are increasingly at risk, making mitigation all the more important.

Of nearly 600 evacuations affecting 268 First Nations — and more than 130,000 people — between 2009 and 2022, the report found the flood evacuees from Peguis had been stranded the longest.

The auditor general described the federal department as “more reactive than preventative,” noting Indigenous Services spent 3.5 times more money responding to emergencies than helping communities prepare for or prevent them between 2018 and 2022.

Two-thirds of First Nation-led infrastructure proposals that would reduce the impact of natural disasters had gone unreviewed or unfunded, adding to mounting backlogs, the report found.

That’s in part because Indigenous Services’ infrastructure budget (in place until March 2024) dedicates just $12 million a year for these proposals, though the department can use funds from outside that budget when available. Over four fiscal years, the department spent nearly $74 million on these infrastructure projects — 40 per cent more than was budgeted.

Indigenous Services told the auditor general the current backlog of infrastructure projects would cost at least $291 million to complete, meaning it would take more than 24 years to fund them all.

“First Nations communities are likely to continue to experience emergencies that could be prevented or mitigated by building the infrastructure,” the auditor general wrote.

Sutherland thinks the auditor general’s report could have been a driving force behind the new multi-government collaboration, but regardless of the impetus, he’s happy to see the community’s calls getting answered.

“I’m really happy this year with that partnership in place. … We qualified for the additional funding that put us in a more proactive position, and I’m even more happy now because we did not flood,” Sutherland says, emphasizing the last four words.

While he won’t give too many details about the plans being discussed in those meetings, he’s confident the work they’re doing will bring evacuees home for good.

“It’s at an excellent stage,” he says. “There’s going to be a lot of happy people.”

So far, efforts have focused on the housing crisis. There are hundreds of homes to repair, restore or rebuild — but this time they’ll be built to withstand future floods. New housing developments are underway, raised above the 1-in-200 year flood levels the community saw last year.

In an emailed statement, Indigenous Services Canada said long-term mitigation planning is “complex” and the work is still in preliminary stages, but noted the department is working with stakeholders to address housing needs and repatriation of evacuees. The department said it provided $18 million to the First Nation between May 2022 and March 2023 for both flood recovery and 2023 flood preparation.

Sutherland has a hopeful, if modest, vision for the future of his community.

“I’m not saying that Peguis is not going to flood going forward — we likely will,” he says. “But we’re going to get to that point where, yes, Peguis flooded, but I’m glad to report that there have been no reported damages and no need for any evacuations.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On March 17, federal Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre...

Continue reading

Racing against time, dwindling habitat and warming waters, scientists are trying to give this little-known...

From investigative reporting to stunning photography, we’ve been recognized with four 2024 CAJ Awards nods...

The Narwhal is expanding its reach on video platforms like YouTube and TikTok. First up?...