A massive Rockies real-estate project wins another court battle. Opponents will keep fighting it

Residents and nearby First Nations wanted a new environmental impact assessment of the contentious project....

“I want you to photograph my last breath.”

That’s what Warren Simpson told photojournalist Ian Willms in 2019 as he navigated terminal cancer up in Fort Chipewyan, Alta.

Warren had been diagnosed with a rare form of bile duct cancer known as cholangiocarcinoma. The rate of contracting bile duct and gall bladder cancers in Canada is 0.003 per cent. But it’s not as rare in Fort Chipewyan: there had already been three cases of bile duct cancer identified by 2014, a figure a government report pegged as “higher than expected.”

Ian was well aware. He’d been making reporting trips to Fort Chip, as locals call it, since 2010 after reading about a doctor who was raising concerns that the oilsands — a few hundred kilometres upstream from the community — could be causing elevated levels of cancer in the local population.

Warren had spent his adult life working in the oilsands. He enjoyed it, he told Ian in his final days, despite also holding the belief that his cancer was linked to the mines.

When Ian came to The Narwhal to pitch us a photo essay on Warren, we knew it was an important story that needed to be published. And so this past weekend, nearly a year in the making, the piece landed on our site: A life — and death — in Fort Chipewyan.

It’s about Warren, but also so much more: health concerns, a failed promise of a federal study and a community that’s grappling with the legacy of residential schools.

I caught up with Ian to learn about how he approached the story and what it was like getting to know a soft-spoken man with a laugh that could fill the room.

That’s right. I started reading about Fort Chipewyan in 2008. I was fresh out of school and being a recent student I wasn’t confident enough to just jump on a plane. So I did a lot of research and called the community a few times. By the time I got there, it was 2010.

Even though I didn’t know Warren when I started, Warren was the reason I kept going. Because I remember starting this work and I was hearing about people like Warren — I was hearing about these cancer rates and about people dying too young and what that does to the community, but I had never seen it. And of course I believed it was happening, but I needed to see it to photograph it. And in order to see it, I had to be welcomed into an extremely intimate and exclusive kind of situation with a family. Part of me felt like the work would never be done until I was able to witness that.

In a word, it has to happen organically. But the long answer is that you have to approach stories like this with a very clear understanding of your position as an outsider and how you will never be part of the community — but you can come close. And that only comes from being very open and sincere and vulnerable. And particularly as a white city boy coming up to a fly-in, northern Indigenous community, I had to really have a profound degree of respect. And I don’t think there’s any faking that. Sometimes as journalists we might feel like we’re kind of putting it on a bit in order to have certain doors open or get people to talk to us.

But I cared right from the beginning, right from the first time I read about Fort Chip, and that was what I led with. I really gave a shit about what they were going through and the people I met could see that. They could see that I was naive and young, but they could also see I really cared and that I was trying. In a lot of ways Fort Chipewyan taught me to be a good storyteller and a good journalist.

When I was a younger photojournalist I kind of subscribed to those classic tropes: “shine a light,” “give a voice to the voiceless,” “photography can change the world.” There’s this white-savior complex a lot of photographers have to overcome. Any photographer who comes from a place of privilege and goes in there with this kind of savior complex can fall into that trap.

I always had a strong sense of empathy in my work from the get-go, but I had to really understand the futility of photojournalism in order to effectively wield its power. And part of going up against a story that’s so incredibly big — and also, from my perspective, just getting bigger with every step I took, in terms of what I knew had to be done — that futility really came into sharp focus for me.

When I started out, I thought, if people could just see this, it would help somehow. And sure, it does help for us to know about it, but documenting an environmental disaster and a cultural disaster as another step in the broader trajectory of settler colonialism in Canada and the world is important because future generations and future leaders will have a much better understanding of this context.

I could tell you if I went through my archive, but perhaps what’s more interesting is that I’ve lost count. I did the math at one point and I think I was averaging about a month a year of field work on this project. And then I won a grant which funded a great deal of travel and I put quite a lot of work into the project in 2018 and 2019. I would say over 10 times.

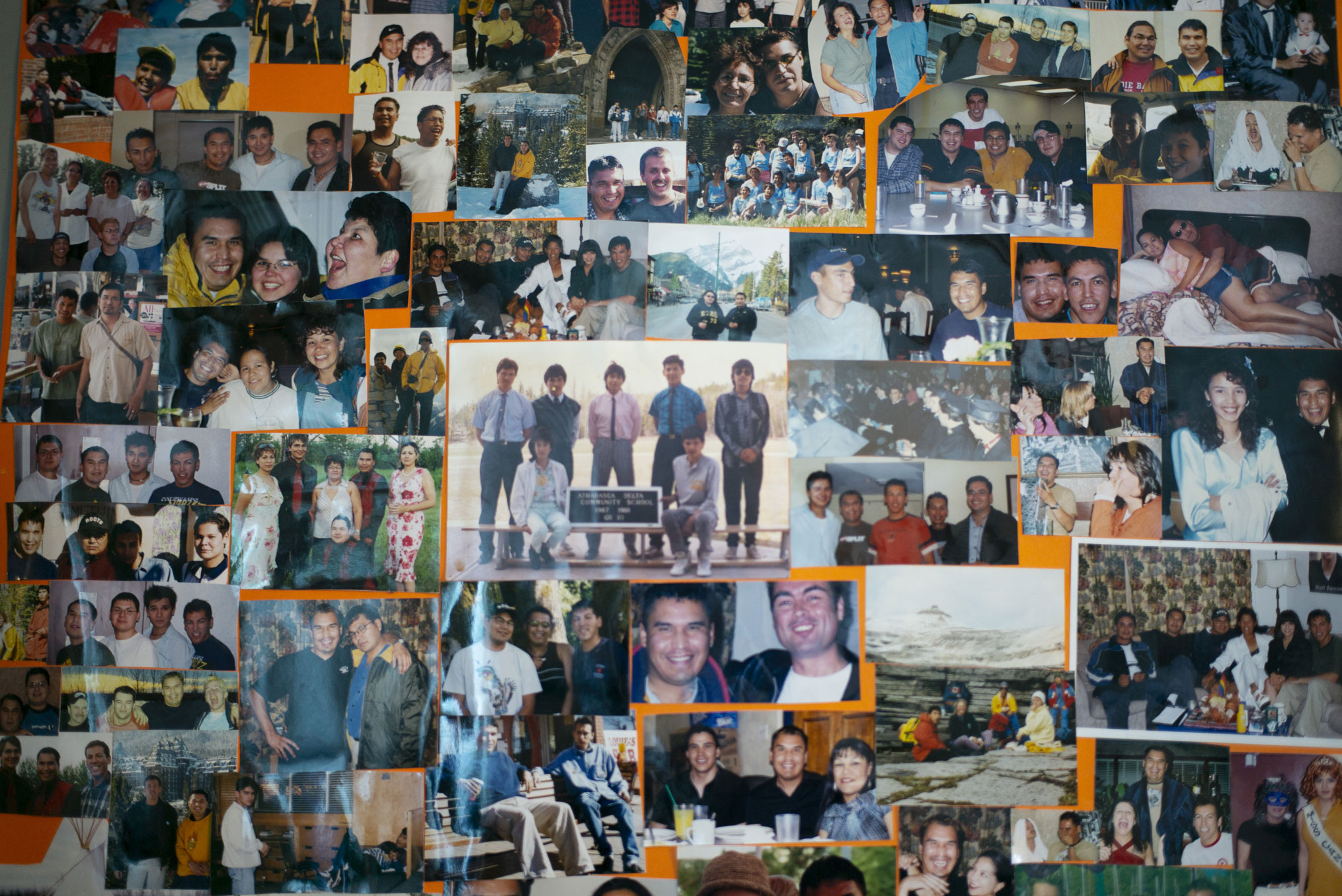

When I first met Warren, I didn’t know he had cancer. I had gone to a birthday party with Alice Rigney. She is a friend of mine in Fort Chip that I met on my first trip there — kind of like a teacher, mentor. She’s a Dene Elder. I went to this birthday party for her grandson. Warren was there because Alice is Warren’s aunt. I remember my first impression of him was he was just a very sweet, soft spoken and kind man with a wonderful laugh. Just a nice guy to be around.

And the other thing that really struck me about Warren is that he was sitting in the one spot in the house where when the clouds broke, the sun came through the window and it just hit him like a spotlight. I remember sitting there, like, not knowing anything about him and thinking, “this is really incredible light, I should really take a picture of this guy.” But I didn’t really know him. I was at the birthday party in more of a social capacity and I wasn’t sure if it was my place to photograph him in that moment. But I just kind of looked at him in this beautiful light and I thought, there’s something about this guy. After the party, Alice told me that Warren had cholangiocarcinoma. And I asked Alice if Warren would be comfortable talking to me about that and she said he would. So we met up after that and the relationship took form from there.

I made a point to spend a good amount of time with Warren for the rest of that trip. We drove around in his truck and he liked being photographed so I was taking his picture and we were just chatting a bit about his time working for Suncor. It was an interesting thing to meet somebody who was Indigenous who had worked in industry, who was very open about it, who was also affected by this cancer — because it made the whole story far more grey, in a sense. It was really powerful to talk to Warren about the way he felt about working for industry versus seeing the environmental impacts in his community and ultimately contracting a lethal cancer he believed came from oilsands.

Reporting on Indigenous issues as a white person carries an extra degree of responsibility and it’s not something I take lightly. I think there are a lot of very important discussions happening in our industry right now about “parachute journalism” and journalists reporting on places and cultures they don’t have lived experience with. And it’s true, these can be very, very big problems, and they can lead to journalists turning in work that is actually doing harm in communities. But I’d like to think it can be done — outsiders can report on these things in a fair and just way. It’s just important to recognize that there’s extra work involved in terms of bridging that gap.

Yeah, exactly. One of the most important things I would like to say is that I owe a huge thanks to editors Sharon Riley and Denise Balkissoon. They really helped a lot and without them the piece wouldn’t be nearly as effective. So thanks to them especially and everybody at The Narwhal for seeing potential in, and being brave enough to publish, this project in its entirety.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On March 17, federal Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre...

Continue reading

Residents and nearby First Nations wanted a new environmental impact assessment of the contentious project....

Growing up, Christian Allaire loved spending summers with his cousins in his grandma’s backyard, near...

B.C. previously allowed mineral claims without First Nations consultation. It was court-ordered to fulfill its...