Family farmers in British Columbia were already struggling. Then Trump started a trade war

A trade war could help remake B.C.’s food system, but will family farmers be left...

Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre was met with rousing applause last week as he laid out a vision for a prosperous northern Manitoba that hinges on the contentious Port of Churchill.

His plan — built in part around the idea of shipping oil through the port — has attracted increasing attention from Canadian leaders in recent months, putting Churchill’s future into the national spotlight.

Poilievre’s remarks formed part of a speech on Canada’s future, hosted by the Frontier Centre — a Canadian “think tank” that’s come under fire for climate change denial and a history of anti-Indigenous rhetoric — in a ballroom at Winnipeg’s RBC Convention Centre.

More than 500 people crowded around lunch tables to hear Poilievre’s plan to uplift “common people,” remove the “gatekeepers” to Canadian industry and fight the “anti-energy, anti-resource” laws of the current Liberal government. As his speech lamented carbon taxes and federal red tape that have purportedly hampered Canada’s energy and resource industries, the crowd grew increasingly emphatic in their cheers and applause.

Front and centre in his pitch were his hopes for the Port of Churchill. Poilievre isn’t the first to extol the port’s strategic importance to Canada’s economic future — it has been a hotly debated political talking point for decades.

Most recently, Alberta Premier Danielle Smith has invited the premiers of both Manitoba and Saskatchewan to meet in Churchill to discuss developing an economic corridor through the port.

To this day, none of the promises to revitalize Canada’s lone Arctic port — and finally tap into its potential as the key link in a long-promised Arctic trade corridor — have panned out. Some blame the high cost of developing the port, others cite pushback from environmentalists, some claim it’s more conservative talking point than viable plan.

Here’s why an Arctic energy corridor has long been a pipe dream for Churchill — and what may be different this time around.

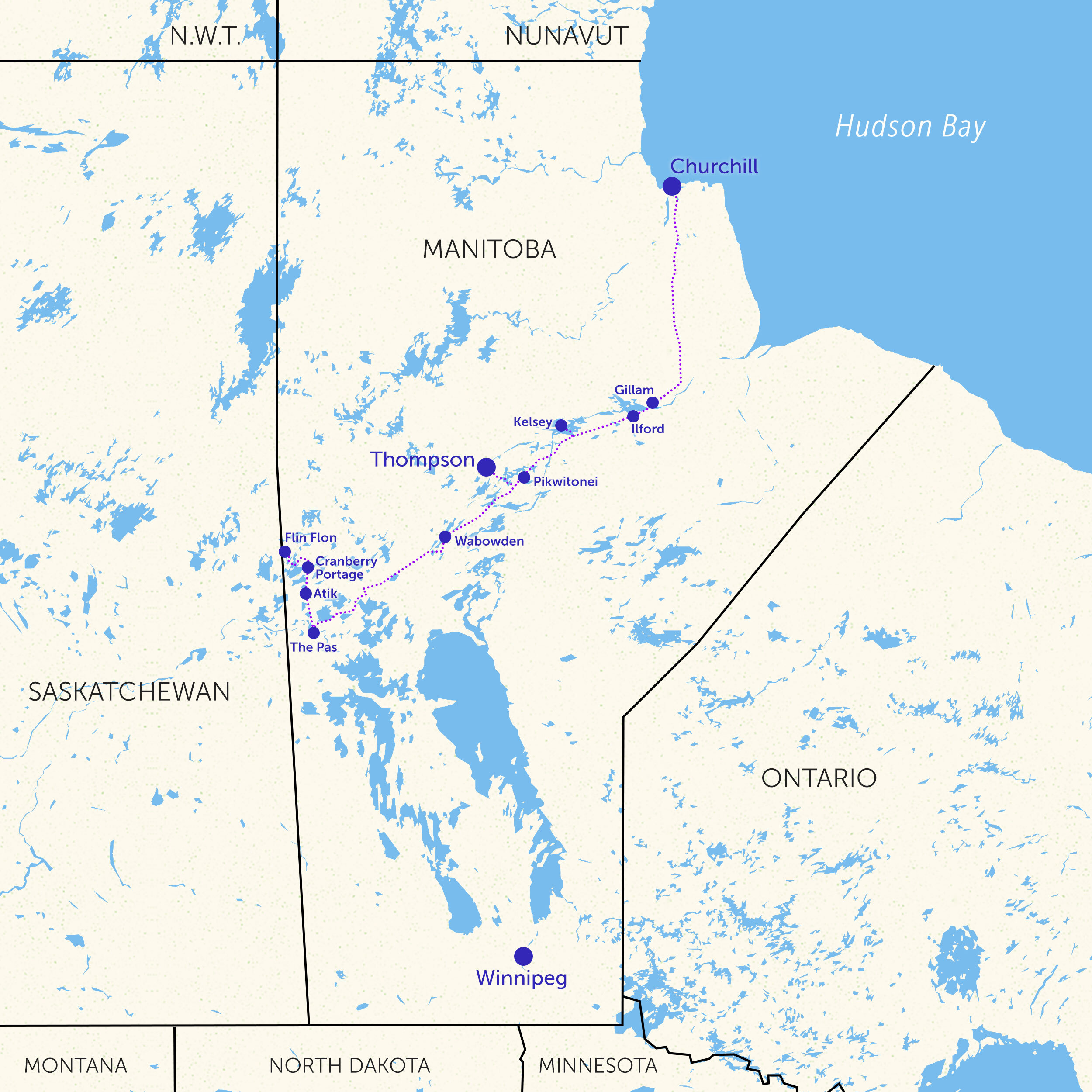

Nestled against the shores of Hudson Bay more than 1,000 kilometres north of Winnipeg, the town of Churchill is home to about 900 permanent residents and Canada’s only deepwater Arctic port connected to the North American railway system.

The 1,000-kilometre Hudson Bay Railway that services the port also carries essential goods like food and fuel to communities from Churchill to The Pas. There are no highways or roads to Churchill; if the railway is out of commission, the only way in is by plane.

More than 100 people are employed by the port and the railway, Churchill Mayor Michael Spence says in an interview. Hundreds more work in industries that rely on the port for business.

The port is only operational in the summer months (the bay freezes over from fall to spring), but it’s still a key driver of investment and employment for the region.

“We are a port community: it’s critical to not only the community but the region,” Spence says. “It’s a lifeline.”

Since it was built in 1931, the Port of Churchill has been primarily a grain port. As early as the 1930s, Western grain producers took advantage of the port’s proximity both to western industry and international markets.

In its earliest days, the port was used to ship a little bit of everything: fertilizer, sulfur and even Scotch whisky. But the Canadian Wheat Board — a federal body established in 1935 to purchase, market and sell Canadian grain — was historically the port’s steadiest customer. Until its dissolution in 2012, the wheat board used the port to export hundreds of thousands of tonnes of wheat to international customers.

Beyond its trade uses, Spence, who has served as the community’s mayor since 1995, stresses “resupply is really critical” to the port. Communities in Nunavut and Nunavik rely on the port and railway to import food, fuel and other essential goods. The port also includes a marine tank farm, which can store more than 750,000 litres of fuel.

Over the years, as the port has changed ownership from government to private enterprise and now to a consortium of First Nations communities, politicians have debated the merits of diversifying the port’s exports, strengthening its infrastructure and capitalizing on its promised opportunities for Arctic trade.

“The port of Churchill should be more used, it should be enhanced,” Jim Downey, then Progressive Conservative minister of industry, trade and tourism, told Manitoba’s legislature in 1996, a call echoed across both sides of the aisle.

And yet, successive efforts to attract industry investment in the port and railway have come up short, leaving a new generation of leaders to extol its values for the Prairie provinces during campaign seasons. Poilievre is no different.

Though a succession of Prairie politicians, including Saskatchewan’s Scott Moe, have expressed an interest in the port, Poilievre is the most recent leader to champion the idea. Over the course of his campaign, he has promised to greenlight permits to ship oil products through the port (oil already moves through the port and federal permits aren’t actually necessary) under the slogan: “Stop overseas oil, unlock the Port of Churchill.”

More recently, Premier Smith made headlines after publicizing a letter she sent to Manitoba Premier Heather Stefanson and Saskatchewan Premier Scott Moe about the possibility of a new economic corridor through the port.

“The war in Ukraine has highlighted the world’s need for responsibly produced, reliable and affordable energy and food,” Smith wrote. “I believe it is incumbent on our provinces to play a leadership role in expanding and advocating for greater market access, including working together to push for a renewed look at the Port of Churchill.”

While her letter acknowledges the economics of the Arctic port haven’t seemed favourable in the past, she suggests a combination of new technologies, warming climates and international trade disruptions might signal changing tides.

But according to Churchill’s mayor — who also serves as co-chair of the Arctic Gateway Group, current owners of the port and railway — all that political talk hasn’t amounted to much yet.

“It’s not helpful to have politicians say there are permits to ship oil sitting on Trudeau’s desk,” Spence says with a touch of frustration, noting no firm proposals have been presented to the owners. “What we want to focus on are the actual projects and proposals that come along.”

While he won’t weigh in on generalized conversations about oil, natural gas, potash or whatever else politicians have promised for the port, Spence maintains the management team is feeling optimistic about Churchill’s future, too.

“You look at what’s happening in Ukraine and there are opportunities. We have a management team that will look at every aspect of being successful. What does successful mean? Time will tell.”

Before Poilievre, Smith or Moe, a group of private investors were stirring up media frenzy over exporting oil from the port.

OmniTrax, based in Denver, Colorado, had bought the port and the Hudson Bay Railway from the federal government in 1997, in hopes of cashing in on the port’s potential. At first, private ownership was a boon for business.

But the railway was unreliable. As it traversed the tundra and permafrost, the Bay Line was prone to derailments, grain spills and stoppages that made maintenance expensive and investors wary. For years the wheat board comprised up to 90 per cent of the port’s business, and when it collapsed in 2012, OmniTrax saw its investment fall away.

As the situation grew more dire, the company pitched a trial shipment of 300,000 barrels of Alberta crude oil to market through the port. The plan sparked national debate.

“It was a conservative scheme to ignore the wishes of communities and develop oil-by-rail,” Eric Reder, who heads up Manitoba’s Wilderness Committee, says in an interview.

Back then, Reder says news outlets contacted him at least once a week to ask his thoughts on the oil-by-rail scheme. His position was clear: “We have to stop every single new fossil fuel project.”

The ecologically sensitive region, home to polar bears, beluga whales, birds and seals, couldn’t handle an oil spill, he says. Reder took the train to Churchill that summer (a 40-hour trip each way) to chat with rail workers and community members. He remembers taking in the disrepair on the railway, seeing a grain car toppled over in the port and tracking just how slowly the train crawled along the tracks. His confidence the port and rail could handle heavy oil cars was low.

Manitoba’s political leaders seemed to agree. Members of the NDP government of the day spoke up about the frequent derailments on the Bay Line and the risks of an oil spill. And that wasn’t all — transportation minister Steve Ashton alleged in 2014 that OmniTrax had “a lack of any real business plan” and no environmental assessments for their oil-by-rail pitch. Meanwhile, Churchill’s council records showed a lack of consistent communication between the company and the town.

In the end, the scheme didn’t pan out. OmniTrax put the port up for sale a short time later, abruptly cancelling the 2016 grain season and laying off more than 100 workers. About 10 per cent of Churchill’s population lost their jobs. The following year, spring floods washed out swaths of the rail line and OmniTrax refused to restore the track, claiming they couldn’t afford the repairs.

With the tracks unuseable, the cost of living skyrocketed in the north as communities were forced to import essential goods by air. Grocery prices reached astronomical highs. All the while, OmniTrax refused to pay. Lawsuits were filed on both sides. For months, Churchill accused OmniTrax of holding the community “hostage” as it played out its financial and political battle, leaving residents to suffer the consequences.

Climate change presents both challenge and opportunity for Churchill’s port.

The Hudson Bay Railway cuts across both permafrost — a thick layer of ice that rests beneath the soil surface year-round — and boggy terrain called muskeg. Muskeg is known to shift and sink under the weight of structures like roads, pipelines and train tracks. Permafrost, too, can heave as it melts from a combination of a warming climate and the heat of trains running over the tracks. Even heavy equipment used to repair the lines can be vulnerable to sinking in the bogs. Trains are forced to travel exceptionally slowly along the rail line to avoid overheating the tracks.

“There’s a lot of shifting in the subsurface,” Chris Debicki, vice-president of conservation organization Oceans North, explains.

“That’s probably amplified by a warming trend. We’ve seen challenges to that infrastructure: that rail line experiences a higher rate of derailments than most rail lines elsewhere in North America.”

The railway also traverses countless waterways that feed some of northern Manitoba’s largest watersheds in Hudson Bay, Seal River and Nelson. Any derailment that spills toxins onto the landscape could have devastating consequences not only for land animals, but for the people and wildlife that depend on those waterways.

Despite the challenges for rail infrastructure, climate change has long been seen as an opportunity for the port. For most of the year, Hudson Bay is coated in thick sheets of ice. Historically, the shipping season has lasted from July to October when the ice melts enough to grant safe passage for ships. But as the Arctic warms and the sea ice melts, the shipping season has started to grow.

“There’s a lot of uncertainty but we do know that there’s been a loss of sea ice in Hudson Bay,

and that loss has been dramatic,” Debicki says.

A 2020 Arctic Council report found the sea ice area in the polar region decreased nearly 30 per cent between 1999 and 2019, while a 2021 report found the number of ships navigating the Northwest Passage jumped by 44 per cent between 2013 and 2019.

Though some models have predicted ice-free Arctic summers by the mid-21st century, Debicki says it’s more likely sheets of permanent ice from further north will shift south as temperatures warm, causing more unpredictable ice floes in the shipping channels.

Any increase in shipping traffic to and from the port would need to be accompanied by formal environmental protections, Debicki says. That’s something the Manitoba and federal governments have so far failed to introduce in the northern waters.

“A vibrant port at Churchill and sound conservation measures and sound marine protection are not mutually exclusive,” Debicki says.

But as for shipping hydrocarbons like crude oil, liquefied natural gas or bitumen pucks, Debicki remains skeptical. Without sound environmental protection and lacking the infrastructure to handle an oil spill in Arctic waters, Debicki doubts a more robust oil export industry would be ecologically or economically prudent.

“I find such proposals bewildering, just even imagining the type of infrastructure investments that would need to be in place,” he says.

“At a time when, as a society, we are increasingly committing to a transition away from hydrocarbons, to put that kind of infrastructure to put that kind of investment into oil spill response, technology and infrastructure development just seems misguided.”

Environmental concerns and costly infrastructure upgrades haven’t dimmed the hopes of Canada’s political leaders, though exactly how invested they are in the port remains to be seen.

When Smith first wrote to Stefanson with the invitation to meet in Churchill, Stefanson seemed — at first — to rebuff her offer, telling media “there are other more pressing things for us to be dealing with right now.”

Two weeks later, during November’s Speech from the Throne, Stefanson seemed to change her tune, suggesting “increased investment” was coming. But in a press conference after the speech Stefanson said her government is “looking at liquefied natural gas, primarily,” when asked about the plan for the port. Stefanson told reporters she had been in conversation with Moe and Smith, adding: “We know with the energy challenges in Europe, with the horrible situation there, the shortage of food potentially, that Manitoba is well-positioned with the Port of Churchill to be able to look at what that could mean in the long term for our province.”

It’s not clear what caused her change of heart. The government said in its response to a freedom of information request that it had no records of internal communications about the port with neighbouring provinces, barring the premier’s October letter. Instead, the office provided several messages from the public chastising the premier for not taking advantage of Smith’s offer. An identical request to Smith’s office turned up 20 pages of records, but the executive council refused to provide those records, citing exemptions related to “advice from officials” and “disclosure harmful to economic and other interests of a public body.”

Spence is tired of being asked whether he approves of oil shipments and natural gas pipelines. Though political conversation about the port abounds, Churchill’s mayor is only interested in real projects, real proposals and real conversation with the Indigenous and northern owners of the port and rail. So far, there are no such proposals on the table, he says.

Suggestions have not been limited to fossil fuels: some say Churchill’s proximity to Manitoba’s hydro-powered electric grid could also open opportunities for shipping renewable power to international regions. Even hydrogen — which Manitoba’s New Democrats have suggested as an alternative to oil exports — could become a valuable export through the port.

Regardless of the next steps, Spence is adamant decisions will be made by those most affected.

When OmniTrax abandoned the railway, a consortium of Indigenous and northern communities operating under the banner OneNorth partnered with the federal government and private industry to purchase the port in 2018. Over the years they restored passenger and freight service on the rails, re-opened the shuttered port, decommissioned the old fuel tanks and installed new infrastructure upgrades to the tank farm, railroad and port. In 2021, government and industry stakeholders backed out, passing full ownership of the port and rail to the 41 communities that make up the OneNorth consortium.

“We said enough is enough,” Spence says of the ownership structure. “It’s northerners, it’s Indigenous people that rely on this lifeline and we will have a say in what the opportunities can and will be.”

“The former ownership, whether it was Ports Canada or OmniTrax, they didn’t live it,” Spence says. “The profits that were made left the communities. This time around … it’s all about making sure that investment and money and opportunities are for northerners and for Canadians as a whole.”

Right now, the group is focused on restoring the railway, ensuring it will stand the test of time as northern Canada’s lifeline.

“Our focus remains on the rebuild underway to bring reliability and excellence to the rail line, establishing relationships and opportunities for re-supply and working with partners and northern and Indigenous leaders on future opportunities for the Port,” Arctic Gateway Group CEO Michael Woelcke said in a statement.

Progress on that front is already underway: a joint investment from the federal and provincial governments in August last year promised $147.6 million over two years to upgrade and maintain the rails. That investment includes a $4.4 million federal investment in a study of the permafrost beneath the tracks. That study, headed by researchers at the University of Calgary, will tackle the complexities of the shifting, frozen ground beneath the tracks to develop more resilient infrastructure.

Already, the Arctic Gateway Group has started strengthening the track with geocells, a type of honeycomb confinement system used to densely pack sand and gravel for a more stable rail bed. Grain shipments from the port were paused this year as the company focused on permanent, long-term solutions to the rail.

“We’re establishing a trade corridor that we’ll be in a position to be taking advantage of,” Spence says. “What’s critically important right now is the investment that needs to go into rebuilding the rail line so we are positioned for future prosperity, and the next number of years will be exciting and important for the region.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. A $335 million funding commitment to fund...

Continue reading

A trade war could help remake B.C.’s food system, but will family farmers be left...

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...

We’re excited to share that an investigation by The Narwhal is a finalist for the...