‘Afraid of the water’? Life in a city that dumps billions of litres of raw sewage into lakes and rivers

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

Ezra Morse didn’t expect to become the centre of a potentially precedent-setting libel case.

“I wasn’t an environmentalist a year and a half ago. I believed it was an important issue, but I didn’t do anything,” he said. “I’d never written a letter to any political party or politician.”

But last year the father and software engineer took up environmental advocacy and founded the Qualicum Nature Preservation Society in opposition to a development — now abandoned — that was proposed for a sensitive wetland in a corner of the seaside town, which looks out onto Straight of Georgia off the east coast of Vancouver Island.

The experience buoyed Morse, who now, as president of the society, is vocally opposing a new development proposal by a different company in a small, 80-hectare forest in the Qualicum Beach greenbelt, which is filled with trees that form part of the the smallest and most at-risk coastal Douglas fir biogeoclimatic zone in British Columbia.

But this time, Morse’s decision to speak up has landed him in hot water.

In May, developers Richard and Linda Todsen, served Ezra Morse and the Qualicum Nature Preservation Society each individually with a libel claim. Deborah McKinley, another local who runs a Facebook page called Concerned Citizens of Qualicum Beach, was also served.

The suit alleges Morse was misleading in his outspoken advocacy against the project, damaging the reputation of Todsen Design and Construction through months of public criticism, including numerous posts on social media.

Morse’s lawyer, Chris Tollefson, of the Tollefson Law Corporation and founder of the Pacific Centre for Environmental Law and Litigation, said the case is an example of a SLAPP suit, or a ‘strategic lawsuit against public participation,’ which can be used by companies to silence and out-resource opponents.

On July 6, Tollefson filed a motion to dismiss the Todsens’ claim, using a fairly new B.C. law, the Protection of Public Participation Act, which was unanimously passed in 2019 and designed to protect free speech from intimidation lawsuits. Ontario, Quebec and B.C. are the only provinces in Canada with anti-SLAPP laws.

The new B.C. law has been applied in just a handful of cases, but Tollefson, who is also a professor of law at the University of Victoria, said Morse’s case may be the first time the legislation is being used to defend an environmentalist or conservation group against defamation claims arising from land-use disputes.

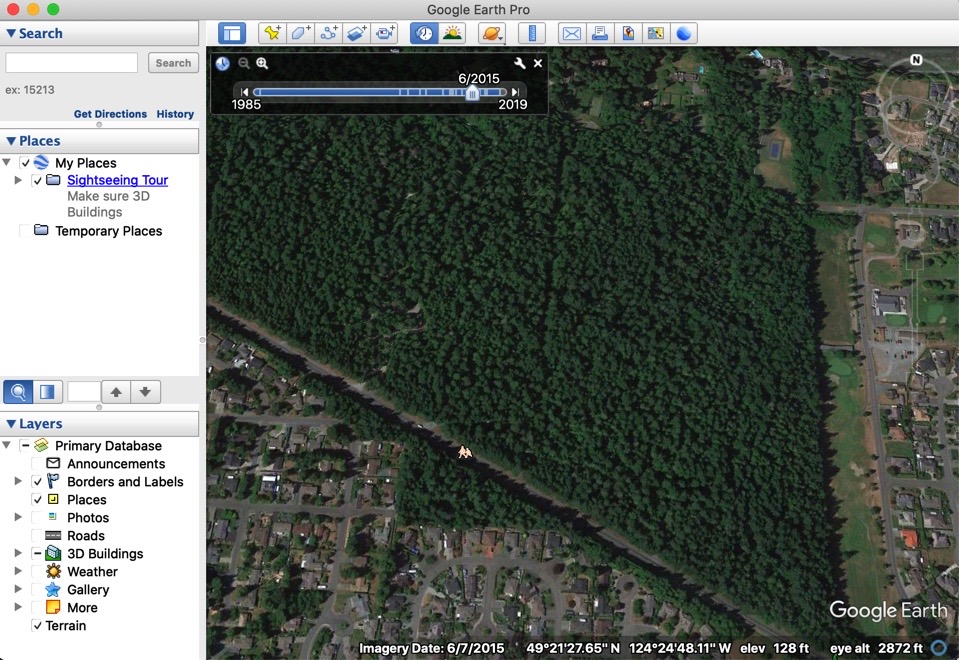

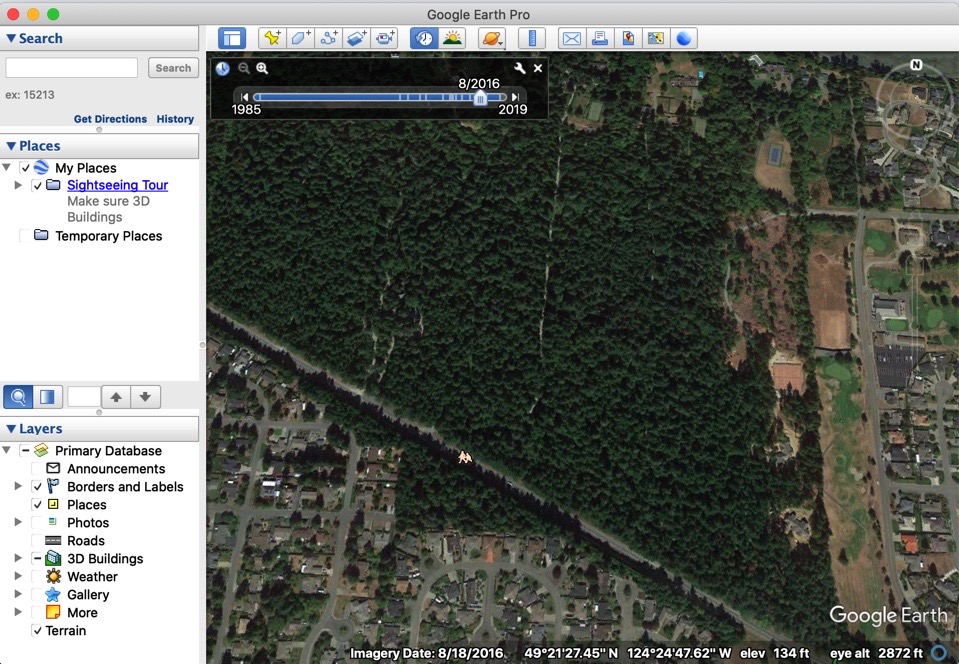

In 2016, the town’s zoning bylaws allowed for Todsen Design and Construction to clear two and a half hectares in woodlands, known as the estate residential lands, to build two homes. The company is now seeking approval from Qualicum Beach council to rezone the lots to accommodate up to 28 units.

The development falls outside the town’s urban containment boundary, which is designed to curtail sprawl and protect conservation areas and rural lands. Morse said that he is not against new housing and agrees the Todsen Design and Construction development is small. But he said he was worried it could lead to other development that cuts into the greenbelt, which is part of a dwindling coastal Douglas fir biogeoclimatic zone.

“On its own, it’s semi-inconsequential. They’ve already logged the land,” Morse said in an interview. “What we’re fighting against is the precedent, because if this [project] goes forward, then perhaps the lot next door will go forward.”

As of 2015, human activities have disrupted about 49 per cent of the coastal Douglas fir biogeoclimatic zone landbase, according to a report by the Coastal Douglas Fir Conservation Partnership. The zone is composed of a narrow strip along the south coast of British Columbia, including parts of the Gulf Islands and the southeast coast of Vancouver Island, including the Regional District of Nanaimo, where Qualicum Beach is located. Less than one per cent of remaining coastal Douglas fir forests are classified as old-growth. Eighty per cent of the zone is privately owned and, because rules that limit logging on private lands are near non-existent in B.C., protections for these last-remaining strips of coastal Douglas fir are hard to come by.

“We aren’t doing much to protect it because we all live here,” Morse said.

Morse also emphasized the coastal Douglas fir forest is also part of the Mount Arrowsmith Biosphere Reserve, a UNESCO-recognized region, which are seen as models of sustainable development around the world.

Morse is not the only person with concerns about the project. In 2019, Qualicum Beach staff, led by Rebecca Augustyn, a city planner, recommended to council that it should not approve Todson Design and Construction’s development application.

“We cannot support this application, as it conflicts with most of the town’s policies regarding residential development and does not meet any of the housing needs that are specifically identified in the [official community plan]. Furthermore, this change would be inconsistent within the town’s longstanding commitment to comprehensive planning,” a memorandum authored by Augustyn reads.

Morse and others have voiced concerns that the development requires an amendment to the town’s official community plan, but the Todsens say that is not out of the ordinary.

“It is a legitimate and normal application process that occurs in every municipality all the time,” Linda Todsen said in a public hearing held on Zoom in February. At the hearing the Todsens, who have been in the development business for three decades, said they had never encountered such ”hostility” to a project and argued they are creating housing in the middle of a housing crisis.

The Todsens say Morse’s advocacy against the development proposal has been damaging to their company’s reputation and the duo are seeking relief for damages.

In their notice of civil suit to Morse, the Todsens allege that several of the statements were defamatory, including the fact Morse referred to the land as ‘protected.’ In public statements, Morse often references the town’s official community plan, which proposes a plan to protect the area and has the objective to “preserve” the estate residential lands. But the Todsens argue those statements are misleading because the land is not formally protected.

Morse said he stands by the statements he made.

“If the core of the argument is that I called these lands ‘protected’ rather than ‘preserved,’ I would suggest the courts have more important matters to deal with than semantic games,” he told The Narwhal.

Morse also posted online comments about the fact the forest is part of the rare coastal Douglas fir bioregion, and the Todsens allege this gives the impression the project “will remove conservation of one of the last intact coastal Douglas fir forests on Vancouver Island.”

The Todsens’ claim also lists a series of social media posts they refer to as “bribery statements” in which they allege Morse falsely implied the Todsens bribed the mayor with campaign contributions.

The Todsens’ legal counsel, Daniel Reid, told The Narwhal that the Todsens could not be made available for interviews since the matter is before the courts.

Reid said he and the Todsens had yet to reviewed the July 6th application and affidavit material filed by Morse and the Qualicum Nature Preservation Society.

“I can advise that the Todsens intend to oppose this application, and will be filing an application response in due course which sets out their position in detail,” Reid said in an email.

B.C.’s Protection of Public Participation Act requires that if a lawsuit targets a person who is lawfully expressing themselves on a matter of public interest, the onus is on the plaintiff to show the court their case still has substantial merit and should be allowed to proceed.

If the plaintiff can’t meet this onus, the courts are “basically bound by the law to dismiss the case,” Tollefson told The Narwhal.

“This isn’t just an issue about freedom of expression or protecting our democracy,” Tollefson said. “This legislation is an attempt to ensure that the courts’ time and resources are not wasted by cases being dragged out that really don’t belong in the courts.”

The Regional District of Nanaimo, which includes Qualicum Beach, recognized coastal Douglas fir ecosystems “have been heavily impacted by human activity” in its regional growth strategy bylaw.

“Population growth and associated development continue to pose a threat to remaining coastal Douglas fir ecosystems along with other ecosystem types,” the bylaw reads.

The bylaw sets out a goal to “conserve and enhance biodiversity and ecological services through the protection of ecologically important features and corridors including floodplains, shorelines, intertidal areas, stream systems, aquifers and urban forests.”

According to the town’s official community plan, the estate properties provide a buffer between the sensitive shore and the nearby highway.

The Todsens applied to build a 16-lot subdivision at 2075 Island Highway and 850 Eaglecrest Drive. The project would impact just a small portion of the overall greenbelt, but would also push development further into a treasured swath of forest, which on its far side includes the Milner gardens and woodland, recognized as something of a unique ecological gem.

According to a report authored by the Mount Arrowsmith Biosphere Region Research Institute in 2016, the Milner woodlands is a “rainshadow forest,” with “warm, dry summers and mild, wet winters.”

“This relatively rare, yet extremely productive ecosystem accounts for 0.2 per cent of the province and contains the lowest volume of old-growth, which raises concern for conservation of these forests,” reads the report.

“Whether you are in favour of this project or not, it is a very sensitive area of the town,” said project opponent Lance Nater at a public hearing about rezoning the land in February.

A second public hearing about the rezoning was scheduled for July 7, one day after Morse and his counsel filed their application for dismissal. The developers cancelled the hearing at the last minute.

Morse suspects this is because the town recently estimated that the developers would have to pay almost $1.1 million back to the town as a community amenity contribution, which is a condition of rezoning.

Morse said last year, he walked through the town’s wetland with his son, and they saw an area that had been clear-cut, and his son asked, “why isn’t anyone doing anything?”

He said that question has been a motivation to him ever since. But he knows he’s a controversial figure. Like many cities and towns, Qualicum Beach is embroiled in debates about the best path forward to address housing, conservation, the climate crisis and the community’s needs.

“I guess I became public enemy number one,” he said. “But for others, [I became] a valuable spokesperson for causes that are really important to them.”

While there have been some heated exchanges, Morse said he is “proud” of his efforts to protect the “ecology and sustainability” of the area. Still, Morse could be in for a weighty legal battle.

In their notice of civil claim, the Todsens provided a series of examples of statements made by Morse which allegedly harmed their reputation by falsely implying that they are “liars” who bribed the mayor.

On several occasions, Morse referenced the fact that the Todsens contributed to Mayor Brian Wiese’s campaign, calling it a “significant” contribution.

The claim references a post from Jan. 31, 2021, in which Morse said approving the development would be a “betrayal of public trust to benefit the current mayor’s significant contributors.” In Morse’s application for dismissal, he specifies he was referring to council approving the development being a betrayal and says it was not a reference to the Todsens.

According to Elections BC, Richard Todsen donated $180 to the mayor’s campaign. Morse said that may be a small amount, but it is enough to qualify as a significant contributor according to Elections BC, which defines a significant contributor as an individual that donates $100 or more to a candidate. Morse said that makes the statement true.

“We have never indicated that this is enough to ‘sway’ the mayor,” Morse said in an email to The Narwhal. “Rather, we have suggested that the applicant is connected and receiving preferential treatment by the mayor.”

In the claim, the Todsens also list excerpts from Facebook posts that Morse wrote in various private and public Facebook groups, such as “campaign contributors get to [sic] favours … reward contractors with skill & diligence, not those who speculate with political connections.”

They also referenced Morse writing “this is a sham” and “must be nice to be campaign contributors.”

The Todsens say these statements imply that they “made significant campaign contributions to the mayor to encourage the passing of the rezoning application.”

Morse disagrees.

“We have never said under any circumstances that any bribe or quid pro quo occurred,” Morse told The Narwhal. “We have consistently criticized the mayor for preferential treatment of connected individuals, whether they be friends, donors or associates.”

Morse said his criticisms are targeted “directly at the council for their lack of impartiality.”

One contested allegation in the claim stems from a heated exchange at a public information meeting about the development on Aug. 19, 2020, that took place on the Todsens’ property. The Todsens allege Morse “bypassed the registration area, security, sanitizing protocols, and holding a protest sign, trespassed onto the Todsens’ land without being lawfully admitted.” They say they asked Morse to return to check-in and leave his sign, and when he didn’t, they escorted him off the property.

Morse showed The Narwhal a video he says is from that day, which shows Rick Todsen and other men escorting Morse away from the meeting. None are wearing masks. Rick Todsen tells Morse he is on private property, and then gets closer to Morse. Todsen’s arms extend towards the camera until they are out of frame, and Morse says that is when Todsen “shoved” him.

“This is assault, you can’t assault me,” Morse says in the video.

According to the Todsens’ claim, Morse then posted about the incident multiple times on social media, for example writing in a private group to one of Rick Todsen’s children that “your father … yelled expletives at me and assaulted me for bringing a sign to the estate residential public information meeting.” Morse said this is the only time he referenced Rick Todsen’s identity in public.

Morse said the quote the Todsen’s included in the claim is missing context, and that in his message he noted Rick Todsen apologized after the incident, and that Morse accepted the apology.

Morse said he was registered for the event, and that he was told he could only stay if he left behind his protest sign. After the heated exchange, Morse said the organizers made no further attempts to escort him out, and that he agreed to put his sign away and attended the full meeting.

According to the claim another post from Feb. 4, 2021 reads, “Estate residential developer (another significant contributor to the mayor) verbally and physically assault a citizen at their public information meeting.”

The Todsens allege these statements “meant and were understood to mean” that the plaintiffs verbally and physically assaulted someone “illegally and unprovoked.”

Morse said he never indicated the “verbal and physical assaults” were “illegal or unprovoked.”

“I simply said it happened.”

Morse said he doesn’t dispute that a person has the right to keep trespassers off their private property, but in this case, he believed he was permitted to attend a public information meeting that he was registered for — a part of Morse’s story the Todsens contest.

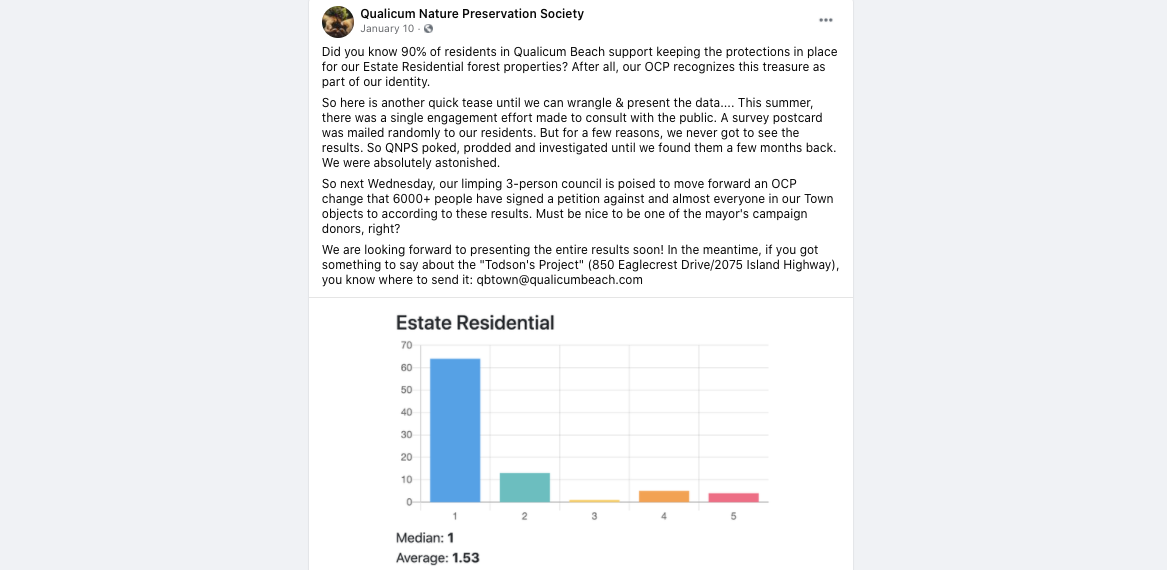

The Todsens also take issue with the way Morse has talked about community opposition to the project. Morse often referenced a survey sent out by then-councillor Adam Walker (who is now an MLA) to about 500 residents, where 73 per cent said preserving the town’s rural greenbelt was “very important.” The Todsens allege Morse used this survey to falsely claim the majority of the community opposes the project.

The survey was eventually renounced by the council, which said it was not officially sanctioned by the town.

The Todsens are seeking an injunction against Morse to prevent him from writing “any similar libel concerning the plaintiffs.” The suit accuses Morse of having “malicious” intent.

Morse told The Narwhal his intention is protecting the forest.

“To me, it’s not an option; if we can’t speak for the trees, there will be no one left to do so,” he said.

Morse’s application for the claim to be dismissed alleges the Todsens took many of the statements by Morse and the Qualicum Nature Preservation Society out of context, sometimes misquoting and “misrepresenting what was expressed.”

“None of the impugned statements would lower the plaintiffs’ reputation in the eyes of a reasonable person,” reads the application. “In any event, all the impugned statements are either justified or constitute fair comment on a matter of public interest.”

“In short, the plaintiffs’ claim is meritless.”

In addition to having the claim dismissed, Morse is seeking to have the Todsens cover his legal costs and pay him “general, aggravated and punitive damages.”

Larry Reynolds, who works as a lawyer for West Coast Environmental Law’s Environmental Dispute Resolution Fund, said this case could have widespread provincial ramifications. The fund provides grants for communities and individuals to hire lawyers at reduced rates, and they are helping Morse. He said SLAPP suits can have a “chilling effect” on activists.

“Citizens often feel very unempowered when it comes to taking on developers,” he said.

But the SLAPP law addresses the power imbalance, he said, and allows a judge to penalize a company for bringing a lawsuit for “improper purposes.”

“It could be a large sum of money,” he said. “This file has real precedent value.”

Reynolds sees the case through a wider lens. Cumulative effects of development and industry are putting higher and higher pressures on the land, he said.

“It’s not just the pipelines, it’s not just the container ships, it’s not just the spills. It’s the small events in many parts of the province … encroaching upon smaller wilderness or rural areas.”

Tollefson assisted in developing B.C.’s first anti-SLAPP law that was adopted in 2001, which was repealed by the newly elected BC Liberal government just months later. It wasn’t until 2019 that legislation was finally passed under the NDP government.

“These kinds of cases have an enormous price for the defendants, economically and emotionally. They pay a price for democratic expression.”

Chris Tollefson, lawyer

Almost 20 years after first advocating for anti-SLAPP legislation, Tollefson said it is “gratifying” to finally be able to access the new law in the court.

“Law reform can take a long time. There will be twists and turns,” he said.

There have been several prominent SLAPP suits in environmental contexts before B.C.’s law came into effect. Logging company Resolute Forest Products launched a defamation case for $7 million against Greenpeace Canada in 2013, which is still caught up in court eight years later.

Taseko Mines attempted to sue the Wilderness Committee for defamation in a court battle that lasted five years, and that the Wilderness Committee eventually won in 2017, two years before B.C. introduced its anti-SLAPP law.

“We are very proud to have stood our ground, but B.C. very much needs anti-SLAPP legislation. We were completely innocent and yet this company was able to keep us in the courts for five years — and their pockets are much deeper than ours,” the committee’s national campaigner, Joe Foy, told The Narwhal at the time.

Tollefson said he and Morse would like to end the case as quickly as possible.

“These kinds of cases have an enormous price for the defendants, economically and emotionally,” he said. “They pay a price for democratic expression.”

Updated on Aug. 9, 2022, at 4:01 p.m. PT: This story has been updated to correct the name of the Qualicum Nature Preservation Society, which was misidentified as the Qualicum Beach Preservation Society.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

Court sides with Xatśūll First Nation, temporarily halting Mount Polley mine waste expansion

Break out the champagne: Emma’s storied life and leadership in journalism has earned her the...