What Carney’s win means for environment and climate issues in Canada

Mark Carney and the Liberals have won the 2025 election. Here’s what that means for...

This is the second part of Carbon Cache, an ongoing series about nature-based climate solutions.

Compared to the Amazon or Great Bear Rainforest, the sprawling peatlands of Ontario’s Far North might seem a bit, well, boring.

“People don’t wake up and go ‘oh yeah, woohoo, decomposing organic material is the best!’ says Anna Baggio, the director of conservation planning for Wildlands League, in an interview with The Narwhal. “It’s not sexy. But it’s hugely valuable and we can’t even begin to get our heads around it.”

It’s true: Ontario’s peatlands — or muskeg, as the wetland ecosystem is often called — offer a mind-boggling range of ecological benefits.

Like tropical and temperate rainforests, the peatlands sequester a huge amount of carbon, storing an estimated 35 billion tonnes of carbon in Ontario’s Far North alone (that’s equivalent to annual emissions from 39 billion cars). The peatlands also serve as critical habitat for wildlife including caribou, wolverines and many migratory birds.

Anna Baggio, director of conservation planning for Wildlands League, poses for a photograph in Guelph, Ont. Baggio says while Canada’s peatlands may not be sexy, they’re invaluable when it comes to the battle against climate change. Photo: Christopher Katsarov Luna / The Narwhal

These benefits derive from the fact that bogs and fens in northern Ontario — especially in the Germany-sized Hudson Bay Lowlands, the world’s second largest peatland complex — remain relatively undisturbed, unlike many other places that have drained them for agriculture or flooded them for hydroelectric dams.

But that may be changing quickly.

Climate change is expected to lead to longer droughts, which will dry out peatlands and undermine carbon storage functions. Permafrost thaw may also accelerate carbon emissions.

Long-planned mining development in the region, an area about 540 kilometres northeast of Thunder Bay referred to as the “Ring of Fire,” could also result in severe impacts to peatlands due to the extraction process and related infrastructure, such as roads and transmission lines.

Combined, these changes are bringing to a head long-standing tensions about who has decision-making powers over the region: the pro-mining province, the conservation-leaning federal government or the dozens of First Nations throughout the Far North — many of which have conflicting views about industrial development in their homelands.

“We want to look after our own selves, with all the resources at our disposal: the air and the muskeg within our traditional lands,” says Chief Bruce Achneepineskum of Marten Falls First Nation, whose leadership supports development, in an interview with The Narwhal. “Therefore we must have a say in it.”

Peatlands are ancient ecological systems, which take thousands of years to form their characteristic layer of absorbent organic soil — but they’re also highly sensitive to impacts.

“If you have any type of disturbance that has the potential to have large-scale changes to how wet the site is or the vegetation community that’s there, you’re going to reduce the ability to store carbon,” says Maria Strack, a Canada Research Chair in ecosystem and climate at the University of Waterloo who specializes in peatland emissions, in an interview with The Narwhal.

Disturbance of peatlands releases carbon dioxide and methane directly into the atmosphere. And while peatlands are already a net contributor of methane, these changes also destroy the ecosystem’s future storage capabilities for carbon dioxide, turning them from a carbon sink into a carbon emitter.

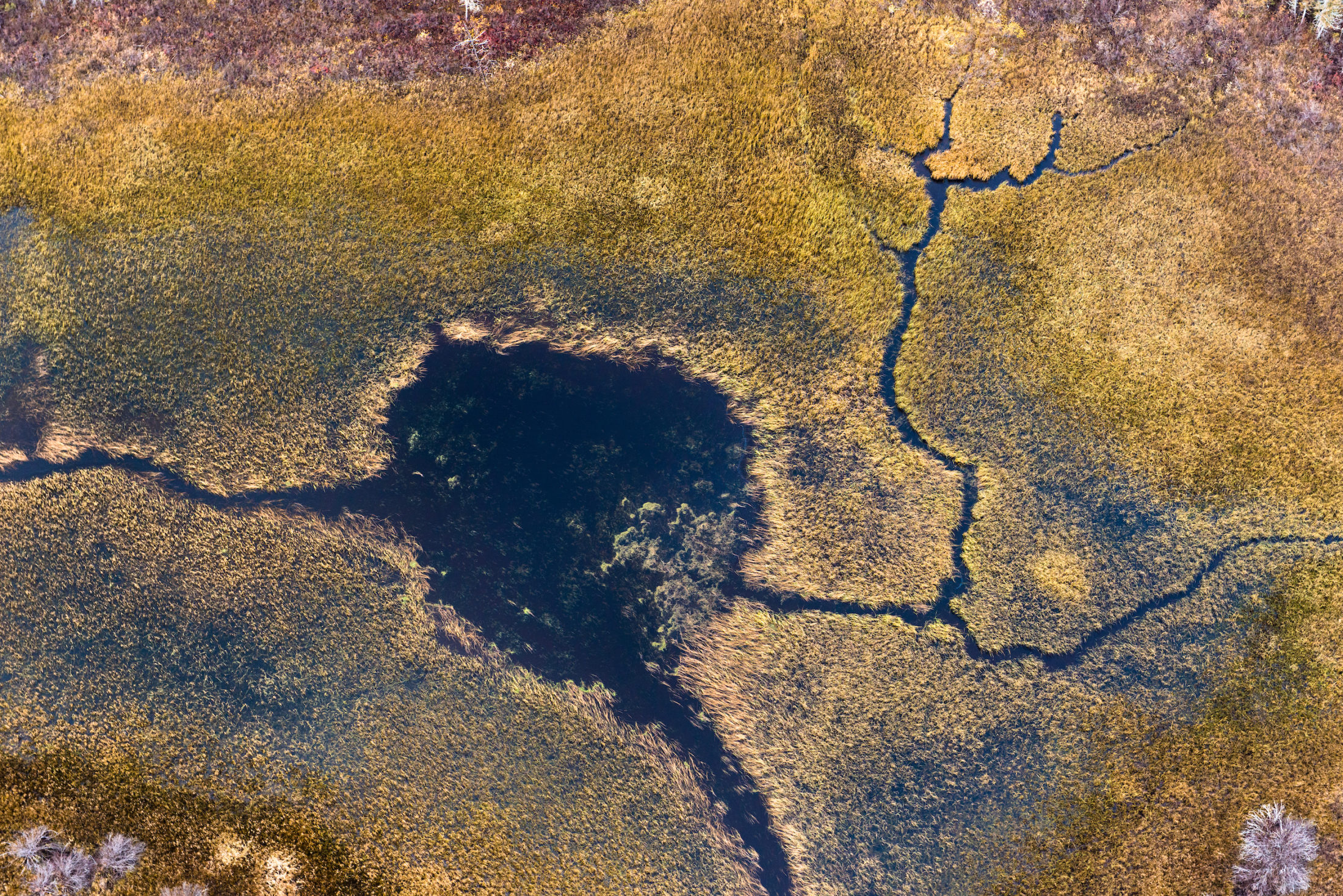

Like tropical and temperate rainforests, peatlands sequester a huge amount of carbon, storing an estimated 35 billion tonnes of carbon in Ontario’s Far North alone. Photo: Garth Lenz

While significant advances in ecosystem restoration practices have been made in the horticultural peat harvesting sector, Strack said it likely takes between 10 to 20 years to return carbon sink functions to rehabilitated landscapes; peat only grows up to one millimetre per year.

But left untouched, disturbed peatlands won’t naturally recover, especially at the far larger scale proposed in the North: “Once it’s built, we really don’t get a do-over,” says Baggio of Wildlands League.

Last year, findings published by Strack’s research team concluded that seismic exploration conducted for Alberta’s oil and gas industry has disturbed at least 1,900 square kilometres of peatland and increased methane emissions by 4,400 to 5,100 metric tonnes per year.

That’s a worrisome trend given that methane has 25 times the global warming potential as carbon dioxide — and that the study underestimated the disturbed area and emissions, meaning “the impact is likely much higher.”

It’s a common theme in northern ecosystem research: scientists know the landscapes are of critical importance but don’t actually know that much about the specifics.

Justina Ray, president and senior scientist of Wildlife Conservation Society Canada, explains in an interview with The Narwhal that northern regions are categorized by the federal government as “unmanaged lands,” meaning emissions related to land-use changes aren’t included in the national inventory — for good or for bad.

Forestry and agriculture in the south gets most of the attention for so-called “land use, land-use change and forestry” emissions, both in terms of policy and scientific priorities. Ray says that “the whole story of carbon mitigation is you have to have a direct threat for the carbon to be of value and accounted for.”

Justina Ray, president and senior scientist of Wildlife Conservation Society Canada, poses for a photograph at her home in Toronto in July. Photo: Christopher Katsarov Luna / The Narwhal

Currently, that direct threat doesn’t exist — so mechanisms aren’t in place to account for emissions from peatland disturbance and to integrate it into decision-making processes.

“We’re not really very prepared to be able to do the real in-depth accounting and carbon estimation,” Ray says. “We’re not positioned for the change that’s to come.”

Northern Indigenous communities have known of the ecological significance of peatlands for countless generations. After all, it’s their land: the “breathing lands,” as elders of Kitchenuhmaykoosib Inninuwug First Nation call it.

“It’s been our source of food and source of livelihood as far as I can remember, back when we used the land quite a lot as a source of our livelihood,” says David Paul Achneepineskum, CEO of the tribal council Matawa First Nations that represents nine Ojibway and Cree First Nations, in an interview with The Narwhal. “A lot of people still think of it that way: their ancestors’ and their grandmothers’ and grandfathers’ way of life.”

The James Bay Lowlands in northern Ontario. Photo: Garth Lenz

But many First Nations communities in Ontario’s Far North live in extreme poverty, alongside decades-old boil water advisories, high food prices and horrific youth suicide crises.

As a result, debates about the future of the muskeg — as a carbon sink or wildlife conservation area — are deeply intertwined with conflicting visions about industrial development, resource jobs, infrastructure and culture.

For instance, Marten Falls and Webequie First Nations are taking active roles in encouraging mining development, serving as project proponents for the provincial and federal environmental assessments of the two roads required to “open up” the Ring of Fire. The first proposed mine is called Eagle’s Nest and would extract nickel, palladium, and copper.

“We should be able to be part of the economy and not continue to be marginalized in our own traditional lands,” says Chief Achneepineskum of Marten Falls in an interview with The Narwhal (Chief Achneepineskum is not related to David Paul Achneepineskum of Matawa First Nations). “All we’re trying to do is get a revenue base and build our own economies in our communities and prosper like anybody else in Canada.”

Webequie has hired SNC-Lavalin to support the nation’s environmental assessment process, while Marten Falls hired engineering giant AECOM. Last fall, Marten Falls received 300,000 shares from Noront Resources, a Canadian mining company that owns the majority of the Ring of Fire’s mining rights

Dayna Nadine Scott, associate professor at York University’s Osgoode Hall Law School who researches Ring of Fire development, says in an interview with The Narwhal that nobody would fault Marten Falls and Webequie for leveraging Ring of Fire development to get long-needed all-season roads built, but that “we should also not forget that Ontario is unwilling to provide the community infrastructure that is required unless it also serves the industry’s needs.

Dayna Nadine Scott, York University research chair in environmental law and justice in the green economy. Scott studies development in Ontario’s Ring of Fire. Photo: Christopher Katsarov Luna / The Narwhal

Other First Nations, including Neskantaga and Eabametoong, have publicly opposed the practice of other First Nations serving as project proponents for the environmental assessment process, arguing in a 2019 letter that “it is inconsistent with the Honour of the Crown to attempt to proceed with a delegated environmental assessment of the project in this manner, and to potentially aim to pit one First Nation against others.”

Similarly, the recent announcement by Premier Doug Ford of an agreement with Marten Falls and Webequie First Nations to complete the “Northern Road Link” to the first proposed mine site in the Ring of Fire was slammed by other First Nations leaders.

Fort Albany Chief Leo Metatawabin responded to the Northern Road Link announcement in a press release, saying that “our people will not accept this,” while Neskantaga First Nation Chief Chris Moonias said: “You can expect opposition if Ontario, or any road proponent, tries to put a shovel in the ground of our territory without our consent.”

Peter Moonias, a community Elder and former Chief of Neskantaga First Nation, posted notices along the Attawapiskat River identifying Neskantaga’s traditional, ancestral, historic and customary lands. This area was proposed as a potential site for a river crossing for future roads connecting the Ring of Fire to the rest of Ontario. Photo: Allan Lissner

Lawrence Sakanee, a Neskantaga First Nation community member, fishing near White Clay Rapids. Photo: Allan Lissner

Chief Chris Moonias of Neskantaga First Nation fishing near Kabania Lake. Photo: Allan Lissner

The conflict over the muskeg hasn’t always looked like this.

The “Ring of Fire” was first discovered in 2007, leading to a massive rush of mining companies staking claims in the area. Chromite, used to manufacture a key component of stainless steel, was identified as a key resource by companies including Noront.

But in early 2010, several First Nations blockaded airstrips built by mining companies due to concerns about the environmental impacts of building infrastructure on frozen bogs and lack of consultation and benefits sharing with local communities. The two-month blockade was led by Marten Falls and Webequie — the same First Nations now acting as proponents for the roads.

The next year, nine First Nations signed a “unity declaration” asserting their common rights to self-determination and consent prior to development. That was followed by the signing of a regional framework agreement with the province in 2014 and the Matawa Jurisdiction Table in 2017.

Justina Ray holds her hand over the area of Ontario know as the Hudson Bay Lowlands, home to the world’s second largest peatland complex. Photo: Christopher Katsarov Luna / The Narwhal

Both of these at least nominally represented attempts at collaboration between the First Nations and province on planning for the region: while they enhanced existing decision-making processes, they didn’t give First Nations any new decision-making powers.

By mid-2017, Premier Kathleen Wynne announced she had run out of patience and demanded “meaningful progress in weeks, not months” from the First Nations concerning the proposed road into the territory. Only three months later, Ontario announced it was partnering with three of the nine First Nations to build the roads, including Marten Falls and Webequie.

Shortly after, Doug Ford — who had pledged “if I have to hop on a bulldozer myself, we’re going to start building roads to the Ring of Fire” — was elected as new premier of Ontario.

His government, whose minister of mines Greg Rickford was briefly on Noront’s board between political jobs, ripped up the regional framework agreement signed in 2014 and continued to negotiate using Wynne’s so-called “divide and conquer” approach. Ontario is also moving to repeal the province’s controversial Far North Act to expedite development.

In February, the federal government announced it was embarking on a regional assessment of the Ring of Fire region under its new impact assessment legislation.

Scott of York University says this process allows for evaluation of long-term and cumulative impacts of development at a watershed level, including the peatlands. It also presents an opportunity for the federal government to partner with Indigenous governing authorities to co-manage the regional assessment, she says, especially given Ontario doesn’t appear to be a willing partner for it.

“The huge significance of such a big intact ecosystem globally has not been really absorbed in Ontario,” says Scott, who submitted a formal request to the federal environment minister for a regional assessment on behalf of the Osgoode Environmental Justice and Sustainability Clinic. “That’s hopefully something the federal government can see as part of its central mandate.”

Scott submitted a request to the federal government, asking for a regional assessment of Ontario’s Ring of Fire region. Photo: Christopher Katsarov Luna / The Narwhal

Vern Cheecho, director of lands and resources for the Mushkegowuk Tribal Council that represents seven Cree First Nations in the Western James Bay and Hudson Bay region, says in an interview with The Narwhal that they’re pushing for the scope of the regional assessment to include cumulative impacts and downstream impacts to the peatlands and its carbon sink functions, as well as the marine region off the coast of James Bay.

“It’s basically been our goal to look at this whole region as one ecosystem: the watersheds, the wetlands, and the marine region,” he says.

The federal government has allocated funding to more than 60 Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas through the Canada Nature Fund, including exploratory work by Kitchenuhmaykoosib Inninuwug First Nation to establish a protected area in the Fawn River Watershed in Northern Ontario.

As with many other things, the regional assessment is now on hold due to COVID-19. Yet the permitting and staking of mining claims in the Far North continues in spite of protests from First Nations, who have argued they don’t have the time or resources to respond to mining-related notifications while trying to manage a pandemic in under-resourced communities.

Scott says she also fears this delay may mean the regional review could fall behind individual environmental assessments that are still underway, resulting in decisions being made about the roads and peatlands without having to take into account results from the regional assessment.

Noront Resources, the main mining firm operating in the Ring of Fire, remains optimistic about its prospects for mining production by 2024. Noront CEO Alan Coutts says in an interview with The Narwhal that it views the regional assessment as a positive.

“What we like about the federal process is it will bring all of this together,” Coutts says. “Up until now, you’ve done these environmental assessments on these little sections of the road, but there hasn’t been this all encompassing view. The regional assessment will bring that together.”

However, Noront’s shares are currently selling for 15 cents, down from 24 cents a year ago, amounting to a market capitalization of $64 million. Further, the province still hasn’t found the estimated $1.6 billion required to build the road to the Ring of Fire.

An exhaustive Globe and Mail investigation published in October concluded that hype about the region’s alleged $60-billion mining future is “mostly aspirational hogwash” (“don’t even get me started on that Globe and Mail article,” Coutts says in an interview). He concedes a key critique of that article (that the 2012 feasibility study for Eagle’s Nest is outdated), but says the company is updating the pricing information and that the “fundamentals of the project are outstanding.”

One of the metals at the Eagle’s Nest site — palladium, used to build catalytic converters — has skyrocketed in price in recent years. Coutts stresses that much more mining will be required to build electric vehicle batteries and power the “green revolution,” especially nickel. Building the road and Eagle’s Nest would also enable future extraction of chromite — from which chromium is extracted to make stainless steel — at other mines.

Noront’s plan to process chromite in a ferrochrome smelter in Sault Ste. Marie has been met with significant local resistance.

“I’ve got no doubt that there’s probably stuff up there,” says Joan Kuyek, co-founder of MiningWatch Canada and author of Unearthing Justice. “But is it worth what is going to now amount to $2 billion for a road — and the destruction of peatlands?”

Peatlands are the world’s largest terrestrial carbon stores. Photo: Garth Lenz

The future of industrial development in the region remains awfully unclear — but First Nations communities continue to fight for control over their lands.

For the last six years, Mushkegowuk Tribal Council has been conducting baseline studies into the health of nearby rivers. Vern Cheecho, director of lands and resources for the tribal council, says they’re gathering this data before any development starts in order to track future impacts of mining, road-building, and climate change.

Coutts of Noront says there will be no surface tailings or wasterock at Eagle’s Nest, because its waste will be trucked out, and the road will mostly be built on high lands and esker (glacially deposited sand or gravel) material to reduce costs and environmental impacts.

However, a 2015 report by the Northern Policy Institute wrote “string bogs and the muskeg will be a significant hurdle to overcome” when building the north-south road. Cheecho adds that the need to truck the mined materials out increases environmental risk: “There’s always the potential of something happening.”

“How protected are we, really, from upstream development?” he asks. “We don’t know. We’re not just downstream: we’re down-muskeg.”

Recent experience of mining in the area, such as the now-closed De Beers diamond mine near Attawapiskat First Nation that is accused of failing to report mercury and methyl mercury discharge data, also raises concerns for some local communities.

Achneepineskum of Matawa First Nations notes that he’s glad the federal government announced its regional assessment but remains concerned that the province continues to hand out permits without full consultation with First Nations. Achneepineskum says that Ontario’s understanding of consultation is very different from what they believe it should be and that “we want full participation of our membership.”

“This kind of land is most important to our future,” he says about the muskeg. “I’m talking about the world, in terms of climate change. We need to take care of our lands for our future generations.”

The Carbon Cache series is funded by Metcalf Foundation. As per The Narwhal’s editorial independence policy, the foundation has no editorial input into the articles.

Photo caption updated at 4 p.m. PST on July 13 to indicate that Justina Ray is pointing to the Hudson Bay Lowlands on the map, not to the Ring of Fire, as previously stated.

Main photo caption updated at 12 p.m. PST on July 22 to correct the subject of the feature photo for this article. The photo is of Musselwhite gold mine, not Victor diamond mine, as previously stated. Thank you to a reader for bringing this to our attention.

Updated Aug. 9, 2022, at 9:32 a.m. ET: This article was updated to reflect in Metric measurements, rather than Imperial, the number of cars whose annual emissions are equal to 35 billion metric tonnes of stored carbon.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. When I visited my reserve, Moose Factory,...

Continue reading

Mark Carney and the Liberals have won the 2025 election. Here’s what that means for...

An invasive pest threatens the survival of black ash trees — and the Mohawk art...

Xatśūll First Nation is challenging B.C.’s approval of Mount Polley mine’s tailings dam raising. Indigenous...