The Right Honourable Mary Simon aims to be an Arctic fox

Canada’s first-ever Indigenous governor general doesn’t play favourites among our majestic natural wonders, but she...

For small, rural municipalities in Alberta, the fortunes of a single oil and gas company can be acutely felt.

This summer in Mountain View County, a rural area just north of Calgary, gas company Trident went bankrupt, leaving 4,700 orphan wells and hundreds of thousands in unpaid taxes in its wake.

Bruce Beattie, the reeve of Mountain View, which has a population of about 13,000 people, told The Narwhal Trident’s sudden fall places a significant burden on the county.

The county “will be looking at a reduction of half a million dollars in our revenue from the oil and gas sector,” Beattie said.

He’s hopeful the county can survive the shock by tightening its belt.

“When you have 363-odd bridges, for example, to look after and 2,800 kilometres of roads — those numbers are significant,” he said.

“That kind of an impact is definitely going to be felt at the municipal level.”

Mountain View is by no means alone.

Earlier this year, the Rural Municipalities of Alberta — the organization representing Alberta’s rural counties and municipal districts — put out a

press release, saying a survey of its members found many oil and gas companies hadn’t been paying their taxes.

The amount of lost income for rural municipalities, the association said, is “unprecedented.”

The survey found at least $81 million in unpaid taxes from oil and gas companies had accumulated across the province, creating a “significant hole in rural municipal budgets throughout Alberta.”

In 2015, new rules came into effect, requiring for the first time oil and gas companies publicly disclose how much money they pay to governments, from the municipal to federal.

The Narwhal analyzed data filed under the Extractive Sector Transparency Measures Act (ESTMA) to examine how reliant counties and municipalities in rural Alberta are on oil and gas payments for their revenues.

The findings show two thirds of Alberta’s rural municipalities received tax payments from oil and gas companies totalling more than $2 million in 2018.

In some cases, the taxes from oil and gas companies made up more than 90 per cent of local governments’ available tax revenue.

But as the experience of Mountain View shows, a high reliance on industry payments can create a deep vulnerability for local governments that must weather the highs and lows of a sometimes volatile market economy.

The fragility of the tax base is opening up new concerns for municipalities across rural Alberta who are openly questioning measures by the current government to step in and give parts of the industry a break.

Alberta’s rural municipalities — most commonly known as counties or municipal districts — cover approximately 85 per cent of land in the province, which means they are home to a large portion of the province’s oil and gas activity.

Their local governments are responsible for paying for public infrastructure and services, which can include roads, policing, wastewater treatment, parks, libraries and cemeteries.

Though the rural municipalities do have other sources of revenue — property taxes paid by landowners, government transfers, investment income or levies for licenses and permits — many rely extremely heavily on tax paid by oil and gas companies.

The Narwhal’s dive into corporate payments found 20 counties and municipal districts relied on oil and gas tax payments for more than half of their net tax revenue in 2018 (see the bottom of this article for more details on The Narwhal’s calculations).

The Narwhal calculated the reliance of Alberta’s rural municipalities on tax revenue from oil and gas companies using data obtained through the Extractive Sector Transparency Measures Act (see the bottom of this article for a full explanation on how we did this). The results reveal that rural communities are deeply reliant on the industry — and when we talked to local officials, we found communities worried that some companies have simply stopped paying their bills, leaving local governments in a lurch. Map: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

Taken together, the 41 rural municipalities that received more than $2 million in tax payments from oil and gas companies received close to $1.2 billion altogether, The Narwhal’s analysis found. Their total net tax base was $1.8 billion.

That’s a substantial share of rural municipalities’ funding hanging in the balance if oil and gas companies don’t pay their bills.

Estimated portion of net taxes derived from oil and gas companies in Alberta’s top-ten most reliant rural municipalities in 2018, based on The Narwhal’s analysis of data obtained through the Extractive Sector Transparency Measures Act and the 2018 financial statements of each rural municipality. Graph: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

In Woodlands County, a 7,600-square-kilometre rural municipality two hours north-west of Edmonton, the small population has relied on oil and gas taxes for services for its entire existence.

The rural municipality’s mayor, Ron Govenlock, told The Narwhal that around 80 per cent of the county’s taxes are supposed to come from oil and gas companies.

This year, Govenlock said, council was “blind-sided” to find out that some companies in the area were simply not paying.

The Narwhal’s analysis of disclosure data found those companies reported paying only about 17 per cent toward the county’s net tax revenue in 2018.

The county, Govenlock added, is “out $9 million over two years … a revenue stream that Woodlands county depends on to continue its operations.”

“It’s a serious situation,” he said, while also acknowledging that the revenue from the oil and gas industry is crucial to his county’s operation.

“Our population base is way too small to support the area that we are responsible for providing infrastructure for,” Govenlock told The Narwhal. “So the oil and gas industry, unquestionably, has been a real boon for rural municipalities such as ours to help provide those kinds of services.”

“Woodlands County and neighbouring municipalities like Greenview have been blessed to have oil and gas activity in the area,” he added.

“That’s changing, however.”

Govenlock pointed to the closure of a local gas plant as a symptom of the shift.

“A substantial amount of the activity — in terms of conventional oil and gas drilling — has seen substantially less investment and less activity as the resources have been tapped,” he said of Woodlands County.

In the nearby municipal district of Greenview, however, the drilling of unconventional resources deep in the Duvernay formation has exploded, leading to much wealth for that region.

Town of Valleyview offices in the Municipal District of Greenview, which receives the highest per capita oil and gas payments of any district in Alberta. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

That kind of money isn’t flowing in Woodlands County, where Govenlock said the county is “out $4.5 million out of the $11.5 million that would have been generated on a normal year from the oil and gas industry. That’s in excess of a third that has not been paid.”

And that shortfall, he said, led council to vote to freeze all non-essential spending a few weeks ago.

Plans for paving projects and road maintenance have been paused. There’s a hiring freeze on all new staff.

Council recently heard that taxes on everyone — including residents — could have to increase by 15 or 21 per cent over five years, though Govenlock noted that they have not yet reached any conclusions.

And, he said, there are more “challenging decisions yet to come.”

Govenlock is concerned that companies are simply deciding not to pay their taxes — and that the Alberta government isn’t doing enough to ensure rural municipalities get a fair shake.

“The people in the industry that are taking advantage of the rules … what we need to do is ensure that the provincial government that’s ultimately responsible for managing the oil and gas industry understands the impact that failure to pay taxes has on not only the municipality,” he told The Narwhal.

“We do not have tools in the provincial regulations that help us to force these guys to do the right thing,” he added.

Some oil and gas companies, he said, are “simply flouting the process.”

The Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP), the self-described “voice” of Canada’s oil and gas industry, has previously said that rural municipalities in Alberta and Saskatchewan “place a disproportionate fiscal burden on industrial property, including upstream oil and natural gas property.” CAPP declined The Narwhal’s request for comment on taxes paid by producers to rural municipalities, saying the organization “does not comment on company-specific issues such as the individual taxes paid by an operator in a municipality.”

Industry players have echoed CAPP’s concerns about tax rates. When Trident Exploration ceased operations earlier this year, the company’s president cited “extremely high rural municipality taxes” which it said led to “inflated” property tax obligations that made it infeasible to continue operations.

Govenlock doesn’t think that’s an accurate portrayal of what’s going on.

“There’s a multitude of factors that go into any business in terms of its operational cost,” he told The Narwhal. “So to suggest that it’s the tax burden — that’s been consistent for the past 20 years — that is now going to be targeted as the reason that their profit margin is tighter?”

“I don’t buy that.”

Beattie of Mountain View County expressed similar concerns. “I’m in the agriculture sector, so I know all about volatile pricing,” Beattie told The Narwhal. “Our revenues go up and down, whether it’s beef cattle or grain. The market can be very volatile.”

He said some financial planning can go a long way.

“We set aside reserves in the good years so we take care of those years when the income isn’t there. I wonder why these companies haven’t done that,” he said.

“Where have the profits gone for these companies that they say they can’t make it?”

Company payments can vary greatly, with operations run by huge, multinational companies as well as small, local drilling companies.

Some large companies report very large tax payments — Imperial Oil, for example, paid approximately $29.5 million in taxes to the Municipal District of Bonnyville alone.

But many payments to rural municipalities come from smaller companies — as low as $193 — with many reporting tax payments in the thousands, not the millions.

With low commodity prices, larger often-global companies have diversified their operations to remain profitable. It’s often smaller companies, reliant on only upstream production, that are more likely to struggle to pay their bills.

The Narwhal’s analysis found roughly half of all tax payments to rural municipalities were for amounts less than $500,000.

A lack of funds like these force counties to make tough decisions.

In Yellowhead County, west of Edmonton, where oil and gas companies reported paying $49.8 million in taxes in 2018 under the Extractive Sector Transparency Measure Act, approximately 91 per cent of the 2018 net tax base came from oil and gas companies.

But this year, the county reported over $7 million in unpaid taxes, “a figure considerably higher than prior years,” and concluded that oil and gas companies owed some $3.8 million of those outstanding taxes. (Yellowhead County did not respond to The Narwhal’s request for comment by press time.)

“The County is now in the position where tax receivables are approximately five times greater than this period last year,” the council heard in late July. In response, the Yellowhead Council approved a motion to transfer nearly $3 million from an emergency fund to compensate for “noncollectable taxes.”

“It’s not a perfect world … Smaller gas companies are struggling to pay their bills,” Dale Smith, the reeve of the Municipal District of Greenview in northwestern Alberta, told The Narwhal when we visited this summer to ask how that region uses industry money.

It’s not just taxes that some oil and gas companies struggle to pay.

Earlier this year, an investigation by The Narwhal revealed that oil and gas companies owe the Alberta government more than $20 million in unpaid land rents — paid out to farmers and landowners on behalf of delinquent oil and gas companies— accumulated since 2010.

The investigation found that government was increasingly stepping in to pay landowners on behalf of oil and gas companies — payments made to cover for delinquent companies increased 840 per cent between 2010 and 2017.

Alberta taxpayers are increasingly picking up the tab for rents owed to landowners by delinquent oil and gas companies. Photo: Theresa Tayler / The Narwhal

Other rural municipalities are less concerned about companies’ ability to pay the bills — especially those experiencing an uptick in hydraulic fracturing, as in the Municipal District of Greenview, where revenues from the industry have meant a huge windfall for the local government.

Similarly, Brazeau County in central Alberta, home to a fracking boom, reported $25,585,209 in net tax revenue from all sources in 2018. That same year, oil and gas companies reported paying $24,637,988 in taxes to the country — roughly 96 per cent of the entire net tax base of the county.

In an emailed statement, Jocelyn Whaley, chief administrative officer of Brazeau County confirmed the county’s “tax revenue from all non-residential and farmland sources was approximately … 92.1 per cent.”

In its 2018 financial statement, Brazeau County acknowledges there are issues with collecting taxes from a boom-and-bust industry.

“The County is exposed to the credit risk associated with fluctuations in the oil and gas industry,” the statement reads, adding a “significant portion” of outstanding taxes were “receivable from companies in the oil and gas industry.”

In the county, the taxes reported by oil and gas companies are down 12 per cent from 2016, the earliest year for which data is available through the Extractive Sector Transparency Measures Act.

The County told residents that it had identified “efficiencies” and would be able to keep up its level of service, even in the face of a “downturn in the economy and the decrease of tax revenue.” The county’s new budget plans are designed to “minimize the impact to our citizens” of the economic challenges of the oil and gas sector.

But Whaley said in the statement that the problem hasn’t been overwhelming, noting the county “has not encountered any major issues collecting taxes from industrial properties, including oil and gas properties.”

In neighbouring Clearwater county — home to its own uptick in hydraulic fracturing — county officials are similarly betting on companies’ ability and willingness to pay.

The Clearwater River near Rocky Mountain House, Alta., is a major source of water for fracking operations in the county and is also a tributary of the North Saskatchewan River, the sole source of drinking water for Edmonton. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

“The recent changes in the economy have forced many municipalities to be conservative while exercising high fiscal responsibility,” the Clearwater’s communications coordinator, Djurdjica Tutic, wrote in an email to The Narwhal.

But an increase in fracking in Clearwater has also led to an increase in community tensions around industry impacts. When fracking company Repsol was granted permission to withdraw 1.8 billion litres of water from the Clearwater River each year, locals generally supportive of industry vocalized an uncommon level of concern.

The Clearwater River is a tributary of the North Saskatchewan River, the sole source of drinking water for Edmonton.

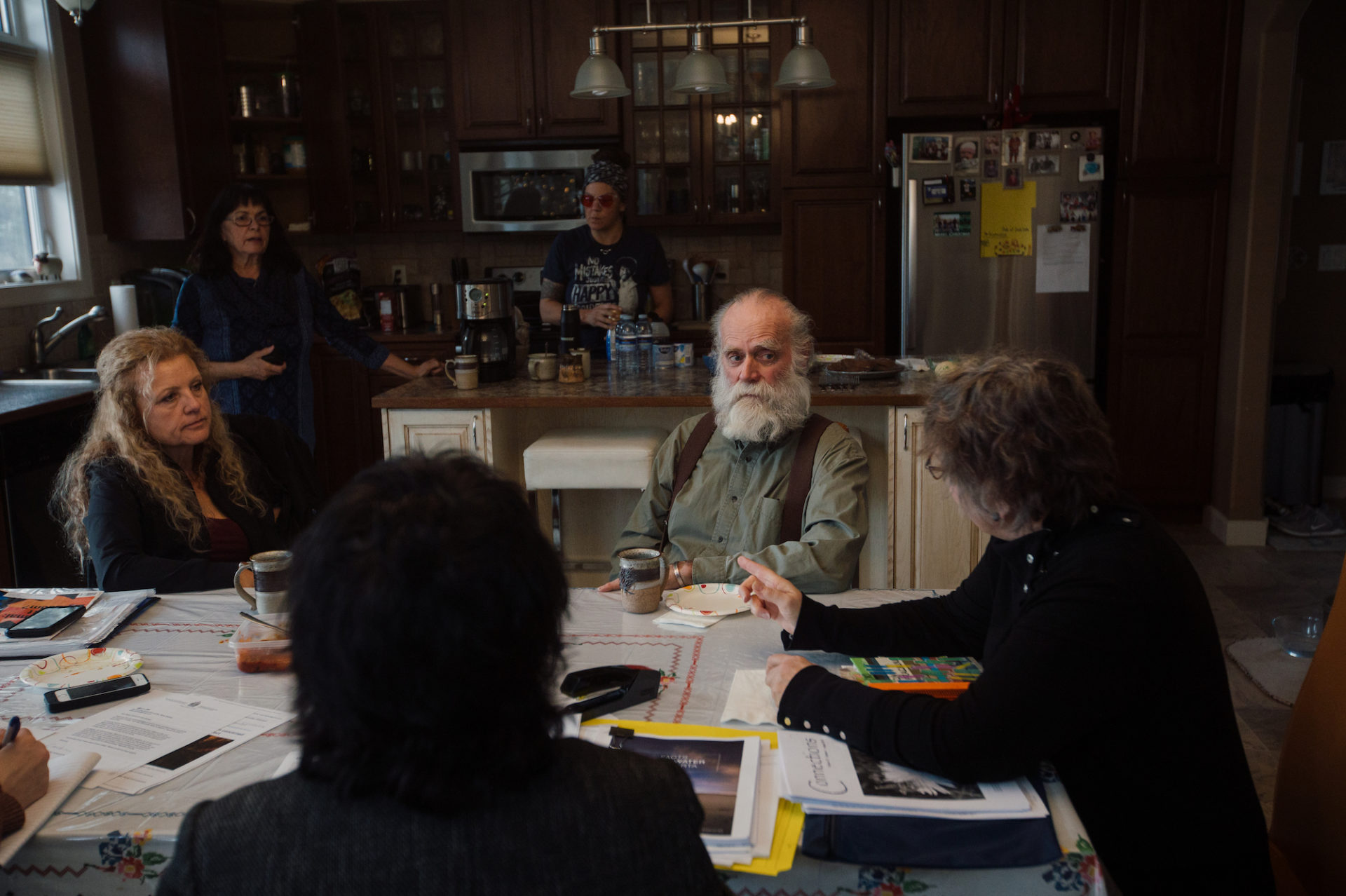

Residents concerned with industrial uses of water from the Clearwater River meet at a resident’s home near Rocky Mountain House, Alta. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

But while there may be concerns about the environmental impact of the industry, the revenue generated continues to be a boon to the community — and they don’t see it disappearing any time soon.

Tutic said the local government in Clearwater is “cautiously optimistic” about the future potential of oil and gas revenues.

Both Brazeau and Clearwater counties sit above the Duvernay, a geologic formation rich in shale gas. A growing demand for the resource in recent years has led to a boom of activity in the region.

But the gas boom hasn’t meant a windfall for many other parts of rural Alberta, where local governments are left holding the bag for profiteering companies that have come and gone.

When it comes to issues with oil and gas companies not being able to — or otherwise neglecting — to pay rural tax bills, Govenlock said the small rural municipalities are “caught in the middle.”

And there’s a frustrating lack of tools available to rural municipalities to recover costs from delinquent companies.

“If they go into receivership, there’s no mechanism in place provincially to allow municipalities to be on the priority list to collect from the assets these guys had,” Govenlock said.

That means, once again, the small local government is left with a big hole in their budget where tax revenues were supposed to be.

Beattie of Mountain View County said there seems to be a different set of rules when it comes to oil and gas companies.

Municipalities are equipped to deal with evasion when it comes to personal taxes, he said.

“If you don’t pay your income taxes, we know that the CRA will clearly be knocking at your door very quickly.”

Oil infrastructure no longer in use in a farmer’s field, near Fairview, Alta., on Tuesday, July 23, 2019. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

But municipalities do not have the same authority when it comes to the oil and gas sector.

“There’s no mechanism in place to force these guys to pay their tax arrears,” Govenlock said, “Unlike a normal residential or commercial property that goes into arrears where we can seize assets and post them for sale.”

“How do I feel about people who walk away from legitimate costs and legitimate bills? I don’t have much respect for people like that,” Beattie said, adding companies need to be “made responsible — just as every other citizen is — to pay their taxes.”

In July, the UCP government announced a new program to cut the taxes some gas companies pay to rural municipalities and said it would, in a roundabout way, foot the bill.

Under the province’s shallow gas relief program, announced in July, companies will get a 35-per-cent cut on taxes on shallow gas wells and pipelines for the 2019 tax year.

This, of course, means rural municipalities will collect less tax revenue. In turn, the Government of Alberta will reduce the amount of education tax the rural municipality has to pay, by the amount forfeited in gas tax. Under the current system, municipalities have to pay the education tax to the government, regardless of whether they were able to collect it.

The government estimates it will be indirectly footing the bill for $20 million in taxes for these companies.

A spokesperson for the Ministry of Energy did not respond to requests for an interview.

The news adds to Beattie’s worry about the budget shortfall his county will face when this temporary measure is expected to end next year.

“We don’t believe [reducing] municipal taxes is the route to save the shallow gas industry,” he told The Narwhal. “I think everyone would say ‘oh my taxes are too high,’ without realizing the services that come with them.”

Under the province’s relief program, Beattie said, “everyone else will pay and the shallow gas guys won’t. They’ll get the services but they’ll be paying less.”

Govenlock of Woodlands County, where companies were behind on $4.5 million in tax payments last year, told The Narwhal the province’s shallow gas relief program won’t help his community, where “a very, very small percentage” of wells qualify under the program.

The government describes 15 counties of Alberta’s more than 60 rural municipalities where the relief program will be most applicable — and Woodlands is not one of them.

Under the program, only companies behind on payments on shallow gas activity would quality — in other words, any oil company, or companies active in deep hydraulic fracturing won’t receive any relief.

Neither then, will the counties that have to remit taxes — on behalf of delinquent companies that don’t qualify — to the provincial government.

“If we don’t get paid [by oil and gas companies], we still have to pay the province,” Govenlock said.

“That’s a real slap in the face to have to pay someone else’s debt.”

***

This article is part of a collaboration between The Narwhal, the Corporate Mapping Project, Publish What You Pay Canada and the Natural Resource Governance Institute. The Corporate Mapping Project is jointly led by the University of Victoria, Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives and Parkland Institute. This research is supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

The Narwhal analyzed 2018 data obtained through the Extractive Sector Transparency Measures Act by looking at taxes that oil and gas companies reported paying to 63 rural municipalities in Alberta. Data was retrieved from Resourceprojects.org and converted from USD to CAD using the exchange rate listed on the website, 0.778629.

We added up the payments reported in each rural municipality to obtain the total amount of tax oil and gas companies had reported paying in each region.

Of those 63 rural municipalities, we found that 41 received more than $2 million in taxes reported by oil and gas companies. The payments reported reflect not what was owed to each rural municipality, but only the amount companies have reported to have actually paid.

We then compared the amount of tax revenue reported through the act with the actual net tax reported in the 2018 financial statements of each rural municipality. This allowed us to calculate an approximate portion of available tax revenue that is derived from oil and gas companies.

This resulted in an estimated reliance on oil and gas taxes. In some cases, the actual portion of tax revenues that are composed of oil and gas tax payments may be different from what was calculated, in part because the data does not include taxes that were assessed but not paid.

Actual net tax revenues were chosen as the numbers represents the amount of tax revenue available for spending — after requisitions and any other revenue sharing — and because the figure was consistently reported across all financial statements we examined. (Net tax revenues do not include what are known as well-drilling taxes, optional one-time charges levied on companies drilling new wells. Our analysis found a relatively small handful of rural municipalities listed this type of tax on their financial statements.)

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. A $335 million funding commitment to fund...

Continue reading

Canada’s first-ever Indigenous governor general doesn’t play favourites among our majestic natural wonders, but she...

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

A trade war could help remake B.C.’s food system, but will family farmers be left...