Ontario’s public service heads back to the office, meaning more traffic and emissions

For 15 years and counting, my commute from Mississauga to Toronto has been mired by...

Back in 2007, construction was halted on a gigantic open pit mine called Galore Creek, located in B.C.’s gold and copper-rich northwest corner. When construction costs more than doubled to $5 billion the plan was abandoned. Ultimately the bold vision on paper could not be made real on the ground — or at least, not at a cost that mining giant Teck-Cominco was willing to pay.

Flashing forward over a decade, an even bigger mine proposal is getting ever closer to becoming real. Or is it?

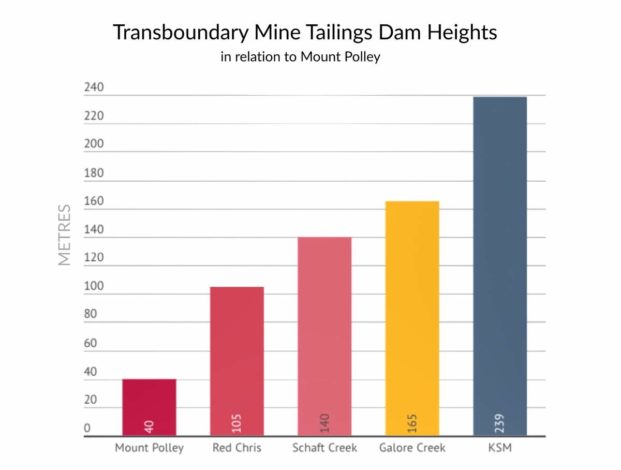

Based on sheer scale and audacity, the plan to build the KSM mine near the Alaska border is more science fiction than resource extraction. Multiple tailings dams will need to be built on the sprawling alpine site over the coming decades: the tallest (240 metres) will stand about 20 metres higher than Nevada’s Hoover Dam. And much of the 2.3 billion tonnes of tailings generated over the 52-year mine life will be perched forever above the salmon-rich Nass River watershed.

Because the copper and gold are so low grade, the miners will have to move and sift through mountains of rock (much of it potentially acid generating) to access the valuable metal — necessitating active water treatment for hundreds of years. Maybe forever.

As of this writing, KSM now has most of its permitting in order, and is just one big step away from starting construction. But will this ever-evolving mine proposal — a throwback to Galore Creek and the WAC Bennett era of wacky 1950s development schemes — ever move beyond being a plan on paper?

Rugged peaks and glaciers near the proposed KSM mine. The KSM mine project is composed of four mineral deposits, the Kerr, Sulphurets, Mitchell and Iron Cap. The view north in this image shows the proposed location of the Sulphurets open pit mine and future waste rock dump. Photo: Garth Lenz / The Narwhal

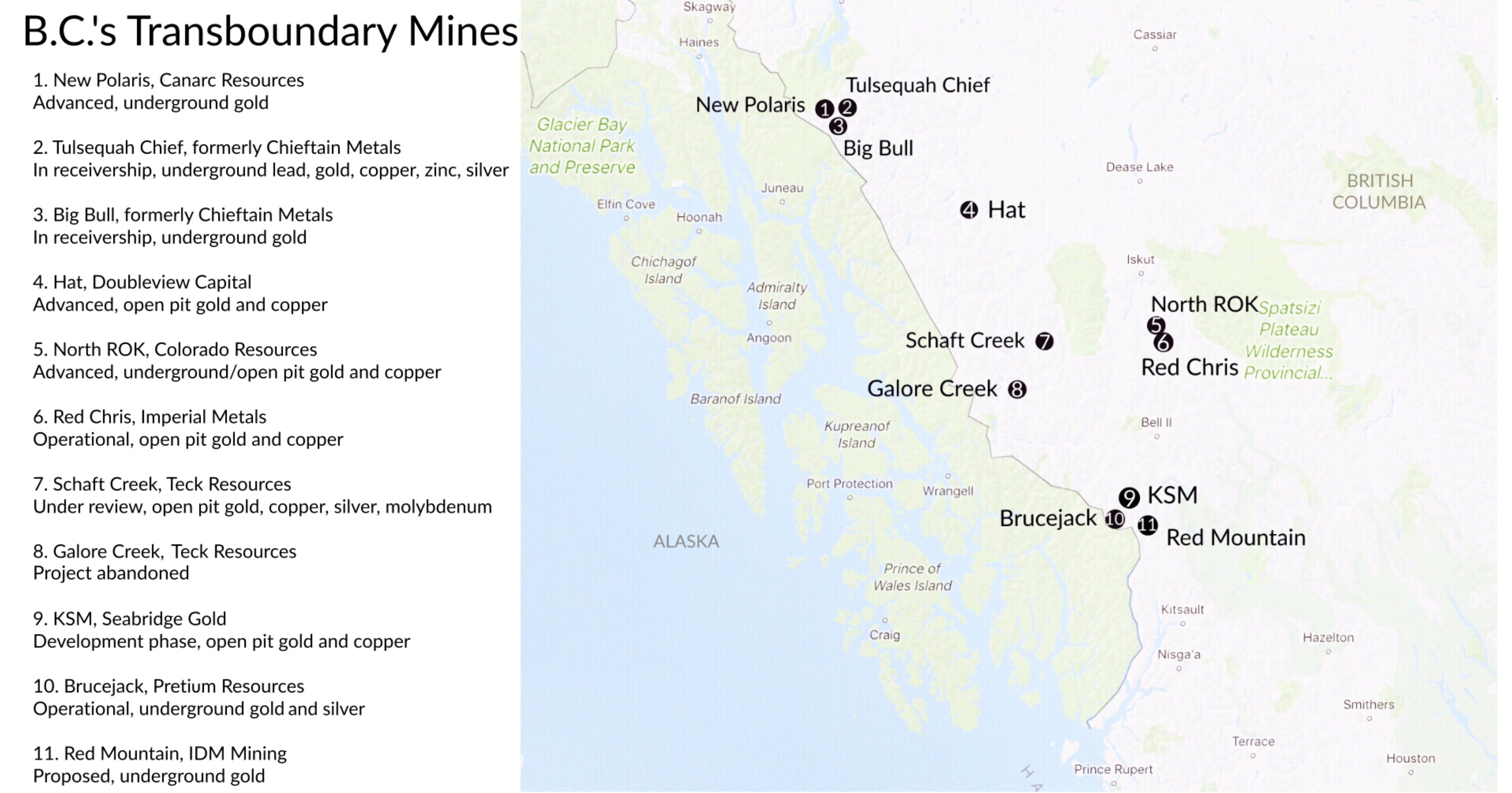

Most Canadians have never heard of it, but KSM is one of the planet’s largest undeveloped deposits of copper and gold by reserves, with lots of silver and molybdenum as well. It’s just one of at least a dozen mines proposed in B.C.’s northwest corner — made economical by a recent $730+ million B.C. Hydro extension of the electrical grid into the region.

Seabridge Gold, the Toronto company behind KSM, does not plan to mine the site — instead, it has explored the property and stickhandled to get most of the permits. The company is currently shopping for a major company to either form a joint venture or buy the “shovel-ready” mine outright. The company has estimated it will cost US$5.005 billion — about $6.5 billion Canadian — to get the project up and operating.

No one has publicly stepped forward yet to invest — but the project has a lot going for it on paper.

“Like Galore, we’re talking about a rugged topography, but it has access to [grid] power, there’s amenable government, and they can sell their [metal] through an available port,” says a financial analyst familiar with the project, who asked not to be named. “But obviously capital is the big one. You’re going to have to want to put down $US5-plus billion.”

This might not be such a stretch, he says. For years big mining companies have been “cash constrained” and focused on expanding existing mine sites, but this appears to be changing. He points specifically to Goldcorp’s June 2017 investment in Chile’s Maricunga gold belt region.

“We’re starting to see the larger companies moving back into greenfields.”

B.C.’s transboundary mines along the Alaska border. Map: The Narwhal

At the end of KSM’s estimated 52-year life, the company has predicted the mine site will require about 200 years of water treatment — to remove metal/minerals from the water that comes into contact with disturbed areas on the site.

But the Alaskan tribes and commercial fishermen living downstream of the proposed waste rock dumps on the salmon-rich Unuk River say KSM could require active water treatment in perpetuity. Based on potential water impacts alone, Robert Sanderson Jr., chairman of the Southeast Alaska Indigenous Transboundary Commission representing 15 member tribes, says mines on the scale of KSM should never be built.

“Who’s going to take care and look after these tailings [and waste rock] sites once the mines close? They don’t have enough money to do that, they have already proven that with Mount Polley. And Canada has a bad history of just up and leaving bad tailings sites as they are.”

The Mount Polley mine had a total tailings storage volume of 44 million cubic metres. B.C.’s massive transboundary mines require much higher volumes of waste storage. The tailings facility at Red Chris can store up to 305 million cubic metres of mine waste. Shaft Creek has a storage volume of 588 million cubic metres and KSM a staggering 1,213 million cubic metres. Graphic: The Narwhal

Sanderson is alluding to the Tulsequah Chief mine, on a tributary of the transboundary Taku river, which has been leaching acid rock drainage into this salmon system for more than 50 years. If many Alaskans distrust promises of mining sustainability from the B.C. side, the Tulsequah Chief is the reason.

Seabridge Gold has maintained that building KSM could end up improving water quality in the Unuk drainage. That’s because the mine, located in the heart of the Coast Mountains, is surrounded by glaciers that are continuously grinding down rock. As a result, there are already elevated levels of metals and minerals in the Unuk tributary waters downstream of the mine. Collecting and treating water as it filters through the mine site can actually result in cleaner water downstream.

Sanderson is not impressed by this idea. “Aquatic life in these rivers has adapted to these preexisting conditions [with high minerals/metal in the water] before miners ever came in,” he says. “So how can they tell us they will make the river system cleaner? I call bullshit on that.”

The tribes are not alone in their concerns. For years, Alaska state and federal officials, environmentalists, fishermen and tribal governments have been reaching out to B.C., Canada and Washington, D.C., to get a greater say in how B.C. transboundary mines are permitted.

(Progress has been slow: last year for example, Alaska conservationists filed a complaint to Global Affairs Canada alleging Seabridge Gold violated international guidelines on consultations with stakeholders, but it was ultimately dismissed.)

Sanderson says many Alaskans will continue to fight proposed northwest mines like KSM.

“We’re not against mining, but we’re against the size and scope of these mines.”

Imperial Metals’ Red Chris mine tailings pond in northwest B.C. Photo: Garth Lenz / The Narwhal

On the B.C. side, the Nisga’a Nation and the Gitanyow Hereditary Chiefs Office have both signed very different KSM agreements with Seabridge Gold. Almost four years ago to the day, Nisga’a signed an impacts benefit agreement with Seabridge Gold that commits the company to provide jobs and contracting opportunities at KSM, annual payments based on a percentage of net profits, and more.

“Bringing prosperity and self-reliance to the Nisga’a Nation is the first priority of [the] Nisga’a Lisims Government,” said President Eva Clayton in a written statement to The Narwhal.

Clayton added that the Nisga’a have engaged in a comprehensive environmental review process over and above the B.C./federal environmental assessment, including a second “voluntary assessment” of the proposed tailings facility, which was initiated by Seabridge in 2016.

“The Nisga’a Nation is satisfied that Seabridge has used the best available technology to ensure the safety of the [Nass river tributary] Bell Irving watershed,” she said.

The agreement with Gitanyow was to provide funding for baseline studies on potentially affected creeks that flow into the Nass river, and does not constitute support for the project, confirmed Joel Starlund, executive director of the Gitanyow Hereditary Chiefs based in Kitwanga, B.C.

Seabridge Gold has proposed to negotiate an impacts benefit agreement with the Gitanyow, he says, but no agreement has been signed to date. In the meantime, the Gitanyow Hereditary Chiefs — continue to assess KSM.

Starlund says the community has recently expressed concerns about the downstream effects of mine toxins like selenium on fish, and the possibility of a big future tailings spill.

“What happens if there’s a catastrophic failure?” Starlund asks. “There’s no plan in place for how to deal with that, or what that even might look like.”

He also points to a systemic problem with the joint federal-provincial environmental assessment processes that saw KSM approved.

“The [government] has to review the project as it is submitted. They can’t recommend that the scope of a mine be reduced by x tonnes/day in order to make it environmentally feasible.”

Like downstream tribes on the Unuk, the Gitanyow rely on salmon for subsistence — including all five Pacific species, although sockeye and Chinook are their food staples. The community is already concerned about chinook with the Nass fishery for chinook being closed last year due to low numbers.

“The dams they build to store their waste are never going to go away,” adds Gitanyow Chief Tony Morgan. “It’s like a ticking time bomb, with us living below.”

British Columbia’s newest mine — just south of KSM — is the opposite approach in many ways to the Seabridge project and by its smaller scale, it may present a more environmentally benign path forward for mining in the northwest.

Instead of establishing open pits and towering waste rock and tailings dams, Brucejack mine is chasing high-grade gold veins underground. It employs a “cut and fill” approach that removes the ore, grinds it up and returns much of it underground, where it is mixed with concrete and sealed.

A glacial highway leads west to Brucejack mine where the Brucejack Lake serves as a tailings impoundment. Further west shows a portion of the proposed location of the KSM mine. Photo: Garth Lenz / The Narwhal

Brucejack is similar to Eskay Creek, a tiny, fabulously rich gold mine built just to the northwest of KSM (it closed in 2008 after 14 years), which employed a similar scale and approach.

Despite its small size, Brucejack is now a major employer in northwest towns like Hazelton; the Nisga’a in May also signed an agreement with the province that could see them earn up to $8 million a year from the mine. (Clayton confirmed this mine currently employs 35 Nisga’a.)

Is this high-grade, lower impact approach to mining something everyone can live with in the northwest?

Guy Archibald, a staff scientist with the Southeast Alaska Conservation Council, says the scale of Brucejack is relatively tiny, but the miners have been permitted to use Brucejack lake as a waste dump. It is not fish bearing, he says, but none of the water draining from the lake will be treated, either.

It’s difficult to compare tiny, super-rich underground gold mines to giant copper-gold porphyry deposits like KSM, says Stan Tomandl, a board member of B.C.’s Fair Mining Coalition. He predicts that KSM will not get built any time soon — but warns that as copper grows increasingly scarce in the world, massive low-grade deposits like KSM will be impossible to ignore.

“The thing that might get [KSM] built eventually is, it will take a lot of copper to wind the generators [required] to get us off of fossil fuels. But that’s 50 years, maybe 100 years away, it’s not right now.”

The smaller footprint is a big plus of Brucejack — but unlike this mine, KSM has actually grown in scope since it got provincial and federal environmental assessment approval in 2014.

Seabridge has continued to drill and find resources. In an updated October 2016 pre-feasibility study, the company announced to its investors a “different approach to developing the KSM Project” that includes increasing mill production from 130,000 tonnes per day to 170,000, and doing less open pit mining and more underground operations.

A spokesman for the B.C. Ministry of Energy and Mines says that if the company wishes to change the project that was approved in 2014 it will need to apply for an amendment — something the ministry confirmed Seabridge Gold has yet to do.

In the meantime, the company has the go-ahead to build roads and a large work camp on the site — but still needs a mine permit to move forward.

Seabridge Gold did not respond to calls and emails to comment on this story. See the questions The Narwhal sent to the company below.*

When the end finally came in late 2007, Galore Creek had more than 400 workers on the ground in northwest B.C. The logistics of moving men and materials across the mountainous topography was a nightmare; adding to the chaos, two separate consultants were unable to agree on what the mine would ultimately cost. The project’s cost eventually ballooned from $1.1 billion in 2006 to about $5 billion in late 2007.

Compared to this past fiasco, KSM has one huge advantage: if and when the mine is ready to move forward, BC Hydro will be there to provide cheap electricity. This fact is a danger to Alaska, Archibald says, because this inexpensive energy access lends an air of credibility and even inevitability to what remains an outlandishly complex and expensive mine proposal.

“The fact that the [northwest] transmission line was built to develop these mines, tells us the province has bet its financial future that these mines do happen.”

The Narwhal Seabridge Questions by The Narwhal on Scribd

*Article update: July 13, 2018 8:30am pst. This article was updated to include an embedded version of questions submitted to Seabridge.

Enbridge Gas will face Waterloo Region in a hearing before the Ontario Energy Board to renew an agreement that would allow the company to continue...

Continue reading

For 15 years and counting, my commute from Mississauga to Toronto has been mired by...

For our last weekly newsletter of the year, we wanted to share some highlights from...

The fossil fuel giant says its agreement to build pipelines without paying for the right...