Ontario’s public service heads back to the office, meaning more traffic and emissions

For 15 years and counting, my commute from Mississauga to Toronto has been mired by...

Thirty kilometres west of Hudson’s Hope, a quiet clifftop town overlooking the Peace River in northeast B.C., is a mountain called Portage. Seen from the air, Portage Mountain is a green triangle with a large fish-shaped splotch of grey, the colour of concrete, tilted off to one side. Two years ago, had you hiked up the mountain, you might have found your ascension blocked by a series of cliff faces. If you were still there at dusk and trained your binoculars on the wide band of rock you likely would have seen tiny dark wisps emerging from cracks and crevices, so ephemeral in the sky they seemed like a trick of the fading light. Eastern red bats and hoary bats. Silver-haired bats and big brown bats. Long-eared myotis bats and long-legged myotis bats. Endangered northern myotis bats and little brown myotis bats, each no longer than your bank card and about the weight of three pennies.

Elsewhere in North America, northern myotis and little brown myotis bats have been decimated by a fungal disease called white nose syndrome that is expected to render some bat species extinct. The fungus, which grows on their nose, wings and body, waking them from hibernation so they often starve to death by spring, is why the two species were listed as endangered under Canada’s Species at Risk Act in 2014. A federal recovery strategy identifies Portage Mountain hibernacula, where bats overwinter in a state of torpor — regulating their body temperature below normal levels — as some of the only critical habitat in mainland B.C. for the endangered bats. Scientists believe the mountain, which has rare geothermal heat vents that likely keep bats from freezing when they hang by their toes during hibernation, might offer a rare northern refuge from white nose syndrome, now creeping westward across Canada and confirmed in Washington state.

The Portage Mountain site was irreplaceable for other reasons as well. Mature birch, aspen and cottonwood trees below the cliff band provided maternal roost sites for the endangered northern myotis bats, where females gave birth and nursed their pups — usually just one, the size of a paperclip when born — in sloughing bark that formed a little lean-to, or in tiny holes left by woodpeckers and rot. Two wetlands offered fresh water, especially important for lactating females who slake their thirst at dusk before spending the night foraging for mosquitoes and other insects. It was highly unusual, scientists said, to encounter such ideal, year-round bat habitat in one “mega-complex,” where eight of the province’s 17 bat species were found.

Today, if you travel to Portage Mountain and are permitted entry, you can walk right up to the cliff face along an industrial access road that leads to the fish-shaped splotch. Dump trucks haul rocks for the relocation of 32 kilometres of provincial highway away from the future flood zone for the Site C dam, currently under construction by BC Hydro. You will find the hillside directly below the cliff face logged and grubbed, and the larger of the two wetlands filled in. If you chance to be there between May 16 and Sept. 14, you might hear a blast, as BC Hydro contractors extract rock from an expanding quarry. The quarry road and its infrastructure are either 300 metres or as little as 30 metres from the endangered bats’ designated critical habitat, depending on the definition of hibernacula you use, which is a matter of some contention between BC Hydro and scientists.

“Bats are intelligent, they’re long lived and they’re creatures of habit. They just don’t pick up their bags and move easily.”

According to documents obtained by The Narwhal under Freedom of Information legislation, BC Hydro developed the quarry over the strong objections of federal and provincial government scientists, after the public utility was advised almost one decade ago of the site’s likely high importance for bat conservation. Throughout the first seven months of 2019, biologists — backed by directors from two provincial ministries and Environment and Climate Change Canada — tried to convince BC Hydro to move the quarry to another spot. In multiple communications, they informed BC Hydro that Portage Mountain had “very high conservation values” for endangered bats, saying there was a high risk bats would abandon the site if disturbed.

The efforts to protect endangered bats at Portage Mountain unfolded as scientists around the world warn we are witnessing the sixth mass extinction event in the planet’s four-billion-year history. As many as half of all species may be headed toward extinction in the next 30 years, in large part due to habitat destruction.

“Could these bats go somewhere else?” asks Cori Lausen, a bat biologist for Wildlife Conservation Society Canada, in an interview. “The likelihood is that they would not.”

“It’s likely the northern myotis and little brown myotis bats have always hibernated in Portage Mountain rock crevices,” says Lausen, a member of the B.C. Bat Action Team, which promotes bat conservation in the province. “That’s all they know … Bats are intelligent, they’re long lived and they’re creatures of habit. They just don’t pick up their bags and move easily.”

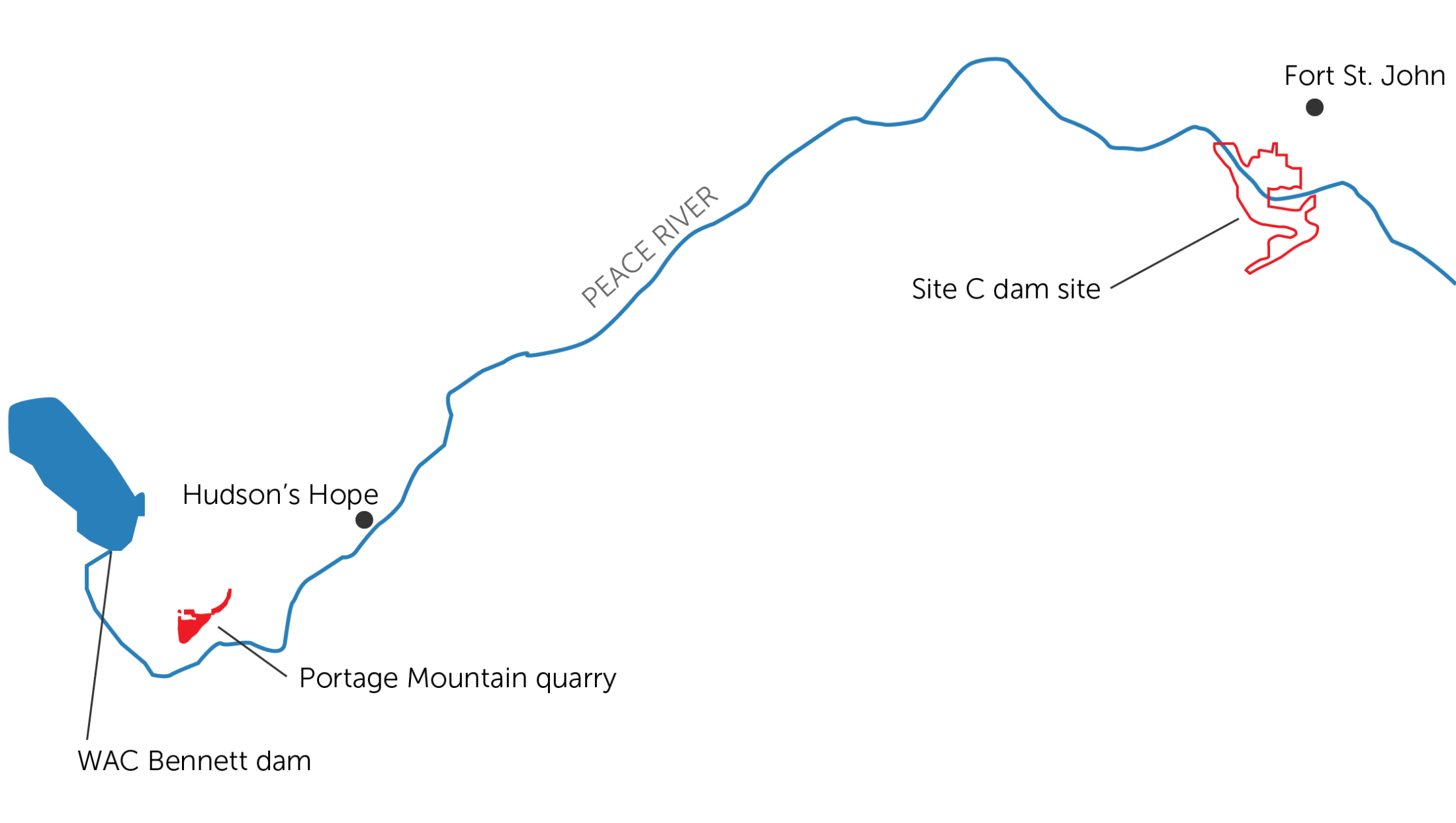

This map shows the location of the Portage Mountain quarry site in relation to the Site C dam. Map: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

In one email in the FOI documents, B.C. Ministry of Environment biologist Purnima Govindarajulu, a small mammal specialist, called the deepening disagreement between scientists and BC Hydro a “hill to fight on,” saying it would set a precedent for other habitat-related issues for species at risk of extinction.

“Why identify crucial habitat if we are not going to protect it when push comes to shove?” Govindarajulu asked in another email to her provincial colleagues. “This goes against so many of our published policies on cumulative effects, environmental mitigation policy, our role in protecting critical habitat, etcetera … ”

The Narwhal requested an interview with Govindarajulu but the B.C. Ministry of Environment said in an email that an interview “will not happen,” underscoring the lack of transparency that has been a hallmark of the troubled $16 billion Site C project. The dam, which is hugely over-budget and behind schedule, will flood 128 kilometres of the Peace River valley and its tributaries, destroying habitat for more than 100 species at risk of extinction, including northern myotis and little brown myotis bats.

According to the documents, BC Hydro’s decision to proceed with the quarry leaves ratepayers to cover unknown future mitigation and compensation costs as part of the project’s burgeoning price tag — on top of $2 million BC Hydro said it has already set aside for bat monitoring and mitigation measures aimed at reducing harm to the two listed species.

Two sources told The Narwhal that BC Hydro might also be obliged to pay compensation totalling “millions of dollars,” once monitoring determines the quarry’s impact on the two endangered species. It’s not yet clear what the compensation would be used for, although it could be put toward a search for other hibernacula, additional monitoring and research and even the creation of artificial hibernacula, the sources said. (The Narwhal is not naming the sources because they are not authorized to disclose the information.)

Ultimately, the documents illustrate the failure of Canada’s Species at Risk legislation to protect endangered species on provincial land and underscore the lack of legal protection for species in B.C., which has more species at risk than any other province and no endangered species law.

“It seems wrong,” says Sean Nixon, a lawyer for the environmental law charity Ecojustice. “It seems counter-intuitive. These two bat species are listed under SARA. There’s a recovery document for them that identifies this particular site that’s being disturbed as critical habitat for the species. But SARA doesn’t actually do anything to protect the bats or that critical habitat.”

Bats, while often maligned, provide many billions of dollars in annual ecosystem services in North America. They fertilize plants and manage insects, including agricultural pests and forest pests such as gypsy moth and spruce budworm. Contrary to myth, there are no vampire bats in North America, the vast majority of bats don’t carry rabies, they don’t fly into your hair and they are not blind.

“Bats are the underdogs,” Lausen observes. “They’re something that a lot of people fear. And we do innately have a fear of things we don’t see. It’s tough to see bats [because] they fly around at night.”

An endangered northern myotis bat. This photo was taken less than 10 kilometres from Portage Mountain, before quarrying activities began for the Site C dam. Northern myotis bats are only the length of a bank card and weigh six to nine grams, about the same as three pennies. Photo: Jared Hobbs

In separate FOI requests, The Narwhal asked the B.C. Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy and the B.C. Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development for 2019 communications to and from B.C. government biologists regarding the Site C dam project and bats at Portage Mountain. Each provincial ministry sent more than 1,000 pages of records in response. Dozens of pages were redacted, some on the grounds they could reveal advice or recommendations developed by or for a public body or a minister.

According to the documents, B.C. government biologists identified Portage Mountain as a high value potential bat maternity colony and hibernation area almost one decade ago, during initial Site C project assessments. “The high importance of this area as irreplaceable habitat for hibernating bats was communicated to the proponent at that time along with a request to find an alternative quarrying site,” said one meeting note. In a July 2019 email exchange with her colleagues, included in the documents, Govindarajulu said BC Hydro “repeatedly ignored our concerns, just saying that it was ‘out of scope’ and that there were no alternatives.”

“Even at the early stage it was clear that mitigating the impacts of quarrying on these bats would be difficult, if not impossible,” she wrote.

Blair Hammond, director of the Pacific region for the Canadian Wildlife Service, says mitigation is tricky for little brown myotis and northern myotis because of the importance of the Portage Mountain hibernacula and roosting sites.

“The fact that they’re using it in the winter and the summer makes mitigation challenging,” Hammond says in an interview. “If, for example, they were only using it as a winter hibernaculum you could do your work in the summer. By the time the bats were ready to come back to hibernate you would have finished any blasting, and tree removal, etcetera, and you would have left a buffer around the hibernacula access point. Theoretically, the environmental conditions would be the same [and] then they should be able to continue to use the site as a functional hibernaculum. When they’re also there in the summer, using the area as a maternity roost, then your ability to mitigate gets harder.”

Hammond, a biologist with bat expertise, says B.C., at first glance, would appear to have plenty of potential bat hibernacula because it has so many mountains and cliffs. But not every crevice, cave or mine meet necessary temperature and humidity conditions, which differ slightly for every species, he says. “Without those hibernacula, they’re not going to be able to persist over the winter. They’re either going to have to leave or they’re going to have to hibernate in a sub optimal spot where they have higher mortality.”

In the documents, BC Hydro said it had a limited ability to determine “consequence likelihood,” referring to its knowledge about the impact the quarry will have on the endangered bats. “This is a huge admission, as most proponents will list a limited likelihood whether they know it or not,” Inge-Jean Hansen, a wildlife specialist for the Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development, wrote in an email to ministry colleagues.

Lausen says biologists don’t yet know how the blasting, quarrying, road-building, logging and the destruction of the largest wetland at Portage Mountain will affect the endangered bats. Vibrations from trucks moving up and down the quarry road with loads of rocks could disturb the bats during hibernation and possibly kill them, she observes.

If the rumbling trucks woke the bats during the first winter of quarrying, in 2019-2020, they could have learned the vibrations “don’t mean their world is falling apart and they don’t have to fly away,” she says.

“It might also be too late. If they do end up burning through their fat, even in that first winter of experiencing these vibrations from the trucks hauling, we wouldn’t know. Those bats would just succumb to starvation and not emerge in the spring.”

“As the bat is disturbed, it will warm up, panicking, thinking it might have to fly, and burn some fat in doing so. And then if the threat disappears, they go back down and keep a nice cold temperature again until they get disturbed again. If the trucks are going by repeatedly, it’s quite possible that these bats are warming up and burning through their fat more quickly than they should, and that means they may not survive the winter.”

Rock is stockpiled at the Portage Mountain quarry for the Site C project. Photo: BC Hydro

Crushed rock or riprap is delivered to the Site C dam site. Photo: BC Hydro

In its environmental impact statement for the Site C dam project, BC Hydro itself noted that construction noise during the winter can cause premature arousal of hibernating bats. “Disturbed bats burn through their energy reserves and can die of starvation before the end of winter. One arousal episode is estimated to cost the energetic equivalent of 68 days of hibernation … Female bats that emerge from hibernations with insufficient fat reserves may be unable to reproduce that year.” The impact statement also said, “Bats that emerge during unfavourable winter conditions are likely to perish.”

The nearest known suitable hibernaculum is at Rainbow Rocks, 25 kilometres away. But Lausen says bats are unlikely to fly very far in search of a new hibernaculum. “They are far more likely to use something that is less than ideal, but in the same area where they typically overwinter.”

Other nearby prime bat habitat has already been lost to industrial development. A considerable amount of high-quality bat habitat in the Peace was submerged when the WAC Bennett dam flooded a vast area in the late 1960s, including a lower arm of Portage Mountain, according to the documents.

“This is simply a reminder that bat habitat has likely been degraded substantially within the watershed by previous BC Hydro projects, which increases the importance of these large-scale habitat features to local and potentially regional bat populations,” said a summary from an April 2019 meeting biologists had with unknown persons from BC Hydro [all BC Hydro names are redacted from the documents] to discuss Portage Mountain quarry plans.

The FOI documents detail months of communications between the unknown BC Hydro employees and members of the Site C vegetation and wildlife mitigation and monitoring technical committee, which included biologists representing both provincial ministries involved. The committee repeatedly raised substantive concerns with BC Hydro that construction and operation of the quarry would harm the endangered bats.

With the full knowledge of BC Hydro, the committee convened a six-person bat expert team, which included Lausen and Govindarajulu, to discuss the proposed Portage Mountain quarrying and provide expert advice about its potential impacts. One plan by BC Hydro to change the quarry road design, greatly encroaching on a promised 300-metre buffer from its “identified” hibernacula, caused particular alarm and was ultimately amended.

“Portage has become very contentious … ,” Hansen wrote to colleagues. (The Narwhal requested an interview with Hansen but the Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development said she was not available.)

In another email, Hansen asked fellow technical committee members Eric Lofroth, a biologist on contract to the B.C. environment ministry and Andrew Robinson, a senior environmental assessment officer for the Canadian Wildlife Service, if they could have a discussion “regarding what I see as scope creep on this project, and the potential for more scope creep before it is done.” Scope creep refers to changes, often harmful, to a project’s scope after it has begun.

“At some point, and at what point, do you just say that you don’t agree?”

Hansen’s next sentences are redacted in the provincial FOI documents, but they are included in the response to a federal access to information request made by The Narwhal on Oct. 9, 2019, and received, in part, on March 31, 2021.

“I would like to know if you have ever had this sort of ever-changing-for-the-worse-plan experience before and how you have dealt with that sort of thing in the past,” Hansen asked her colleagues. “At some point, and at what point, do you just say that you don’t agree? … I know I can only advise but at some point my advice on Portage may be that I just cannot agree to the plan as it is now being written (fully realizing that may not change how they operate).”

On May 2, 2019, BC Hydro informed committee members that it had decided to pursue the development of the quarry over other options such as Bullhead Mountain, 20 kilometres away, where scientists had found no evidence of bat hibernacula and had confirmed the area was not used by endangered caribou herds. The sources who spoke with The Narwhal said an existing quarry at Pine Pass was also considered and that it would have cost $24 million for BC Hydro to change plans in 2019 and source rock for the new highway from Pine Pass — but any potential mention of the quarry was redacted from the FOI documents.

In a letter, BC Hydro told committee members that it would be too costly and time-consuming to change the quarry location and would put the Site C project at risk. “Please understand that this decision was not taken lightly,” BC Hydro wrote.

Ian Parnell, acting regional director for the Canadian Wildlife Service’s Pacific region, subsequently wrote to BC Hydro asking the utility to continue to evaluate other potential rock source sites. He said the wildlife service was concerned that BC Hydro’s proposed mitigation measures would not address potential adverse effects of the quarry development to the maternity roosts of the two endangered bat species. The maternity roosts are not yet listed as critical habitat in the recovery strategy “only because additional information is needed to formulate appropriate criteria … ,” Parnell noted.

“From a biological perspective, conservation of maternity roosts is imperative for the survival and recovery of the species,” Parnell told BC Hydro. Bats “regularly switch roosts during the summer months, moving their pups with them, and likely occupy other nearby roosts” in cliffs, broken rock fragments and trees,” he said. “Some of these other maternity roosts may be located less than 300 metres from the proposed quarry operations.”

In a response letter, BC Hydro reminded Parnell that the conditions of its federal environmental certificate for the Site C dam required it to apply “the best available economically and technologically feasible mitigation strategies.” BC Hydro pointed out that it is not obliged to employ all mitigation strategies, regardless of cost and technical feasibility, “to eliminate all risk of potential harm.”

Karrilyn Vince, regional executive director for the B.C. Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development (FLNRORD), also wrote to BC Hydro after the decision, expressing concern about “the potential high risk of detrimental effects” to maternal roosts in the quarry area, including abandonment, and the general risks the quarry posed to the two endangered bat species.

“Both species are threatened by one of the deadliest wildlife diseases to ever hit North America and birthing and rearing habitat for these species at risk is of utmost importance,” Vince said. Bat experts had concluded “the risks were high and unknown for all activities proposed and that the precautionary principle, or duty to prevent harm when it is in your power to do so, should prevail,” she stated. The factors driving BC Hydro’s decision to progress with the Portage Mountain quarry did not align with the precautionary principle “and thus do not align with the recommendations of FLNRORD at this time,” Vince said.

The B.C. Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy, too, chimed in with a letter, copied to 10 unknown people at BC Hydro, telling BC Hydro “there is a high conservation risk to bats in the Peace River Valley associated with the proposed development of the Portage Mountain quarry.”

The Watson Slough in the Peace River valley. Bats forage for insects around wetlands and rely on them for drinking water. Photo: Byron Dueck

On July 9, 2019, two months after BC Hydro’s decision, a team of provincial and federal government scientists, including Hammond, visited the quarry to see what development had taken place and to determine if they should continue to press BC Hydro to move the quarry to another location, the documents disclose.

Accompanied by Steven Fraser from the Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency, the scientists travelled to the mountain, about 100 kilometres west of Fort St. John, in small trucks for what Hammond characterizes as a “boots on the ground” look to see how close the quarry road would be to the hibernaculum and maternal roosts once it was completed.

Hammond says there was considerable uncertainty about how road-building and quarrying activities so close to the hibernacula and maternity roost sites would affect bat behaviour and if it would lead to bats abandoning the site altogether. “That’s the principal concern that we had from the outset with the project.”

Arriving at the mountain, the scientists discovered that BC Hydro had already constructed the quarry road, which was far more intrusive than they had envisioned from email exchanges. “When I heard I was going to go look at a resource road that was going to be used for development of a potential quarry I imagined something akin to a forest service road up a steep hillside, or something like that,” Hammond recalls. “And this certainly involved more removal of material than I was expecting. There had been tree removal and blasting. The extent to which that had already taken place was a bit of a surprise to me.”

Lofroth, the biologist on contract to B.C.’s environment ministry who joined the trip, wrote in notes from the visit that quarry road development was already fully underway, including blasting. “Clearing for road far more extensive than I understood and realized,” he noted.

The entire slope had been cleared, not just the road right of way. The quarry site had been fully logged, most of it had been grubbed, and the wetland at the top of the quarry — the larger of the two — had been filled in. “The loss of this wetland could effect functionality of area for roosting pregnant and lactating females,” Lofroth wrote.

Lausen says nursing females are close to dehydration after nursing their pups throughout the day, and the loss of the largest wetland could be detrimental if it was being used as a drinking source — not just for the two endangered bat species but for the other six bat species at Portage Mountain. “By saying wetland, you’re saying bats. A wetland is a place where there are a lot of insects being produced. That makes it a really important foraging area for bats. They can’t just fly around willy-nilly. They do need to go into areas where it’s going to be concentrated food … The mothers produce a ton of milk. If that source was available and now it’s not, it could impact them while they’re nursing because they have to travel further and they return several times during night to nurse their young.”

Lofroth and his colleagues also took stock of something else at Portage Mountain that concerned them. Imagery BC Hydro had supplied to the committee and available on Google Earth did not clearly show the extent of the bats’ cliff habitat “and so the proximity of the rock to the roadworks was not apparent until on site,” Lofroth wrote. “Habitat used by bats during winter (and potential habitat during the summer) is now likely only less than 30 metres from cleared area at most.”

BC Hydro had committed to leaving a 300-metre buffer around 16 entry and egress points in the cliff face it identified as the endangered bat hibernacula. But biologists had a different definition of hibernacula that was far more extensive than pinpointing the spots where bats flew in and out. The federal recovery strategy for the bats, the scientists pointed out, says “a single hibernaculum may include multiple entry and exit points and vast underground networks of chambers.”

Lofroth also noted there was much uncertainty about how well the overall cliff feature had been examined or investigated for roosts and entry points and how well adjacent features had been inventoried.

An endangered little brown myotis bat. The photo was taken less than 10 kilometres from Portage Mountain, before quarrying activities began for the Site C project. Little brown myotis bat populations have been decimated elsewhere in North America by white nose syndrome, a fungal disease that kills bats while they are hibernating. Photo: Jared Hobbs.

“Bats can move and use different parts of a rock feature,” Hammond explains. “You’ve got hibernacula, which the bats will be in over the winter, you’ve got maternity roosts, where females and pups will be there during the summer. They will also use these features over the course of the breeding and foraging seasons, even just as night roosts. They’ll go out and they’ll forage, they’ll hang out on the rocks for a while and they’ll go back out and do it again. In the bat biologists’ view of the world when you see a rock feature, and you’ve confirmed that it’s being used by bats, you don’t tend to pinpoint it to a particular spot … The general view of the folks on site was that the whole feature could be important to bats.”

In his notes, Lofroth also said a nearby drainage draw that appeared to have significantly more options for large old trees, making it suitable for maternal roosting sites for northern myotis, had already been impacted by logging for a quarry stockpile and sorting area. In some places, there was no buffer at all from roosting trees, he wrote.

The FOI documents also detail the scientists’ concerns about the effectiveness of BC Hydro mitigation measures aimed at reducing harm to the endangered bats. Mitigation measures to reduce harm to endangered species are required as a condition of federal and provincial environmental assessment certificates for the Site C project.

In a mitigation plan for at-risk bull trout, for instance, BC Hydro outlines a plan to lure the trout up a fish ladder, anesthetize them and truck them past the dam for 100 years so they can reach their spawning grounds (although two out of every five of the larger trout are expected to perish in the dam’s turbines on their journey back downstream and there is no evidence that bull trout, like salmon, will use fish ladders.) The at-risk fisher, a winsome mustelid that dens only in mature trees, will get at least 78 hand-made wooden denning boxes to replace cottonwoods and other old-growth trees that have been clear cut to make way for a Site C dam waste rock dump and the future reservoir. Endangered garter snakes will receive seven handmade dens to replace their hibernacula, according to minutes from Site C vegetation and wildlife technical committee meetings, included in the FOI documents.

As one mitigation measure for the endangered bats, BC Hydro says it will photograph and score bat guano according to size (“none, small, moderate, large”), collecting it for one decade at 120 roosting boxes it will install around the future Site C reservoir. It will then send the guano for DNA analysis to determine which species it belongs to.

Temperature loggers will be installed in the roost boxes and any bat houses not occupied the second year after installation will be “considered for moving to new locations,” according to BC Hydro’s bat mitigation and monitoring plan, included in the documents. “Dead bats found under bat boxes will be collected using disposable gloves, bagged, labelled and frozen for future species, sex and age determination.” BC Hydro also said it would place observers each June and July “at several strategic locations” at five roost box sites to count bats at sunset as they emerge.

The roost boxes have a lifespan of about 10 years and will be “replaced, maintained and monitored throughout the life of the project,” which BC Hydro has alternately said will be 70 years or 100 years. BC Hydro also said it will install a “bat condo” along the edges of the future reservoir, as well as 12 bat boxes at the dam site, mounted on concrete walls or poles. The condo will be outfitted with siding made of shingles or artificial bark “to increase the attractiveness of the structure for roosting by northern myotis,” BC Hydro said in its mitigation plan.

But scientists were skeptical and even downright dismissive of some of BC Hydro’s bat mitigation measures, the documents reveal. Robinson, the senior environmental assessment officer for the Canadian Wildlife Service, wrote in an email to a recipient — whose name was redacted from the documents — that there is “little to no” scientific evidence that northern myotis bats have ever used roost boxes. “Proposing mitigation that will not be effective, in this case for an endangered species, is not credible,” Robinson stated.

Commenting on the mitigation plan for bats, Govindarajulu said if “against all advice” the hibernacula were destroyed then mitigation proposed by BC Hydro was “very skimpy and completely untested.”

“Overall, the mitigation plan is very vague in details and the document does not provide references or literature to suggest that the mitigation measures proposed can be effective,” she noted.

The only exception was the proposed bat boxes, Govindarajulu said, noting that only a few species impacted by the project would use the boxes, and only during the active season. “This leaves most of the impact of the project on bats in the realm of unmitigable impacts … ,” she said, referring to impacts for which there is no remedy.

Some of BC Hydro’s proposed mitigation measures were only aspirational. For instance, the provincial environmental assessment certificate for the Site C project said if the loss of sensitive wildlife habitat could not be avoided, a mitigation plan must include a design for bat roosting habitat in five new Site C dam highway bridges under construction as part of the highway relocation, for consideration by B.C.’s transportation ministry.

Construction at the Site C dam project site. Photo: Byron Dueck

BC Hydro’s initial idea was to install something similar to a “Texas Bat-Abode” — a bat roosting dwelling designed for bridges that can accommodate thousands of bats. But that idea didn’t fly with the B.C. transportation ministry, which had health and safety concerns about putting Texas Bat-Abodes or any other roosting boxes on the new highway bridges. “ … [T]he ministry’s position is that we do not support the placement of bat roosting boxes on any of our bridges … ” wrote Kathryn Graham, regional manager of environmental services for the B.C. Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure, putting an end to the proposed mitigation.

BC Hydro also said bats will be counted at Portage Mountain and at a control site in late June and early August, starting 30 minutes before dusk and continuing for approximately one hour after dusk. “Surveyors will be trained and experienced observers, and will position themselves with a view of the cliff and the light backdrop of the sky to backlight and provide contrast against which to see emerging bats.” The data collected will determine if the mitigation has been effective, according to BC Hydro.

In building the quarry, BC Hydro did not follow the province’s best management practices for bats, which state that high intensity activities, such as those associated with quarry construction and operations, should not occur between October and April within one kilometre of occupied hibernacula. BC Hydro agreed to prohibit blasting at Portage Mountain between September 15 and May 15, when bats could be hibernating. But other quarry activities, such as rock sorting and hauling, continued during the hibernation period.

The best management practices also state that high intensity activities should not occur between May and August within one kilometre of occupied maternity roosts. “Unfortunately, all quarry activities, including blasting, must occur during the maternity roosting period for the quarry to serve its intended purpose,” BC Hydro stated in the documents.

“I find it gut wrenching and incomprehensible that we’re in the midst of a biodiversity crisis and that a rich, industrialized jurisdiction like B.C. hasn’t been able to put down a simple set of laws on paper to ensure that whatever development goes ahead in the province doesn’t go ahead with irreversible loss to the natural systems that support us and our cultures and economies.”

Under Canada’s Species at Risk Act, causing harm to endangered species, their residences or their critical habitat is illegal on federal land — about one per cent of B.C., including parks, post offices and military bases. But it’s not unlawful on provincial land, unless the federal cabinet steps in and starts regulating activities that would normally fall within provincial jurisdiction.

Nixon says only an order from the federal cabinet would have stopped the quarry. Such an order has only been issued twice since the federal Species at Risk Act was passed almost 20 years ago, once to protect the western chorus frog and once to protect the greater sage-grouse.

When the Species at Risk Act was passed, B.C. and other provinces agreed to enact legislation to fill in the gaps and protect at-risk species and their habitat. Six provinces subsequently passed endangered species legislation, bringing Canada into line with the majority of the world’s other industrialized jurisdictions. But B.C. has never passed stand-alone legislation to protect the province’s 1,300 endangered species, despite a 2017 campaign promise from the BC NDP which the party, once elected, subsequently reneged on.

“I’d lay a lot of the blame in this situation at the feet of the B.C. government,” Nixon says. “It should have passed laws years ago to protect endangered wildlife on provincial lands and it hasn’t. It remains an international laggard in that regard.”

“I find it gut wrenching and incomprehensible that we’re in the midst of a biodiversity crisis and that a rich, industrialized jurisdiction like B.C. hasn’t been able to put down a simple set of laws on paper to ensure that whatever development goes ahead in the province doesn’t go ahead with irreversible loss to the natural systems that support us and our cultures and economies.”

Nixon says a sound provincial endangered species law would establish that mitigation and compensation should only be deployed as a last resort, once all other alternatives are exhausted. The first option would be to look at putting a quarry in a location that doesn’t threaten endangered species habitat, he says. “Any good provincial legislation would have required BC Hydro to use one of those other locations rather than using this one, and then conducting a high-risk experiment on the bats by inventing measures that might or might not work with this population.”

In an emailed response to questions from The Narwhal, Dave Conway, BC Hydro’s community relations manager for the Site C project, said BC Hydro works closely with federal and provincial biologists to develop wildlife mitigation programs, including for bats. “Mitigation for bats at Portage Mountain was designed to minimize impacts to the extent practical, to monitor for any observable impacts and to annually report the findings,” Conway said. “Data collected to date suggests the mitigation has been effective.”

Conway said mitigation measures in place at Portage Mountain include sourcing rock away from “the sensitive habitat,” establishing a 300-metre “no work buffer,” designing a new and more complicated haul road to avoid encroaching within the “no work buffer,” minimizing the use of artificial light sources and light pollution, implementing additional noise and bat activity monitoring at the quarry, ensuring all equipment is “well lubricated and has operational manufactured noise dampening” and establishing “lay down areas and storage areas as far from the sensitive areas as practicable.”

According to Conway, all bat species previously observed in the Portage Mountain study area “continue to be present,” including northern myotis and little brown myotis, which would be emerging from hibernation around this time of year. Conway said BC Hydro has committed $800,000 — out of the $2 million it has allocated to date for mitigation and monitoring measures for the endangered bats — “for use by the provincial biologists for additional research to be identified and directed by them.”

Lausen says a final determination about whether or not the hibernaculum has been destroyed, for all intents and purposes, can only be made following monitoring for little brown myotis and northern myotis to help understand the full impact of the quarry. If the bats are no longer using the hibernaculum, biologists will consider it destroyed, she says. “To destroy critical habitat, you either destroy the feature itself or destroy so much around it that it’s no longer usable.”

“ … let’s say there are so many trucks moving up and down constantly that the vibrations make it impossible for bats to successfully hibernate there anymore. You’ve rendered that hibernaculum ineffective. Then you’ve essentially destroyed critical habitat without actually having bulldozed it in.”

Enbridge Gas will face Waterloo Region in a hearing before the Ontario Energy Board to renew an agreement that would allow the company to continue...

Continue reading

For 15 years and counting, my commute from Mississauga to Toronto has been mired by...

For our last weekly newsletter of the year, we wanted to share some highlights from...

The fossil fuel giant says its agreement to build pipelines without paying for the right...