The federal government ‘sees a long-term future for the oilsands.’ Here’s what you need to know

An internal document obtained by The Narwhal shows how the natural resources minister was briefed...

Discussions about a green economy usually centre on transforming the businesses we have to address the climate crisis without too much disruption. The phrase evokes images of solar panels, wind turbines, electric vehicles and maybe even new technology like carbon capture and storage.

But right beneath our noses, there’s another sort of green economy already influencing where and how dollars flow: one based on conserving and restoring nature. Ecosystems left intact are worth money, even if we don’t always recognize it. And not addressing the climate crisis is also very expensive.

For example, Ontario’s Greenbelt — a ring of protected farmland, forests and waterways encircling the Greater Toronto Area — generates $9.6 billion in economic activity per year, mostly from farming, recreation and tourism. It also supports 177,700 jobs, according to the charitable Greenbelt Foundation, and saves the province $224 million every year in natural flood protection. The money spent on restoration projects also ripple out into the local economy, providing both on-site jobs and a need for materials and supplies.

As researchers and communities across Canada increasingly look to restoring landscapes as a way to tackle climate change, they’re also thinking about how to account for the value of natural assets. The issue is the subject of a new guide from the non-profit Natural Assets Initiative that came out this spring, outlining best practices for local governments looking to manage and protect the nature they have.

Here’s a look at a few examples of how nature — kept as is, or being brought back to good health — is already making money move in southern Ontario.

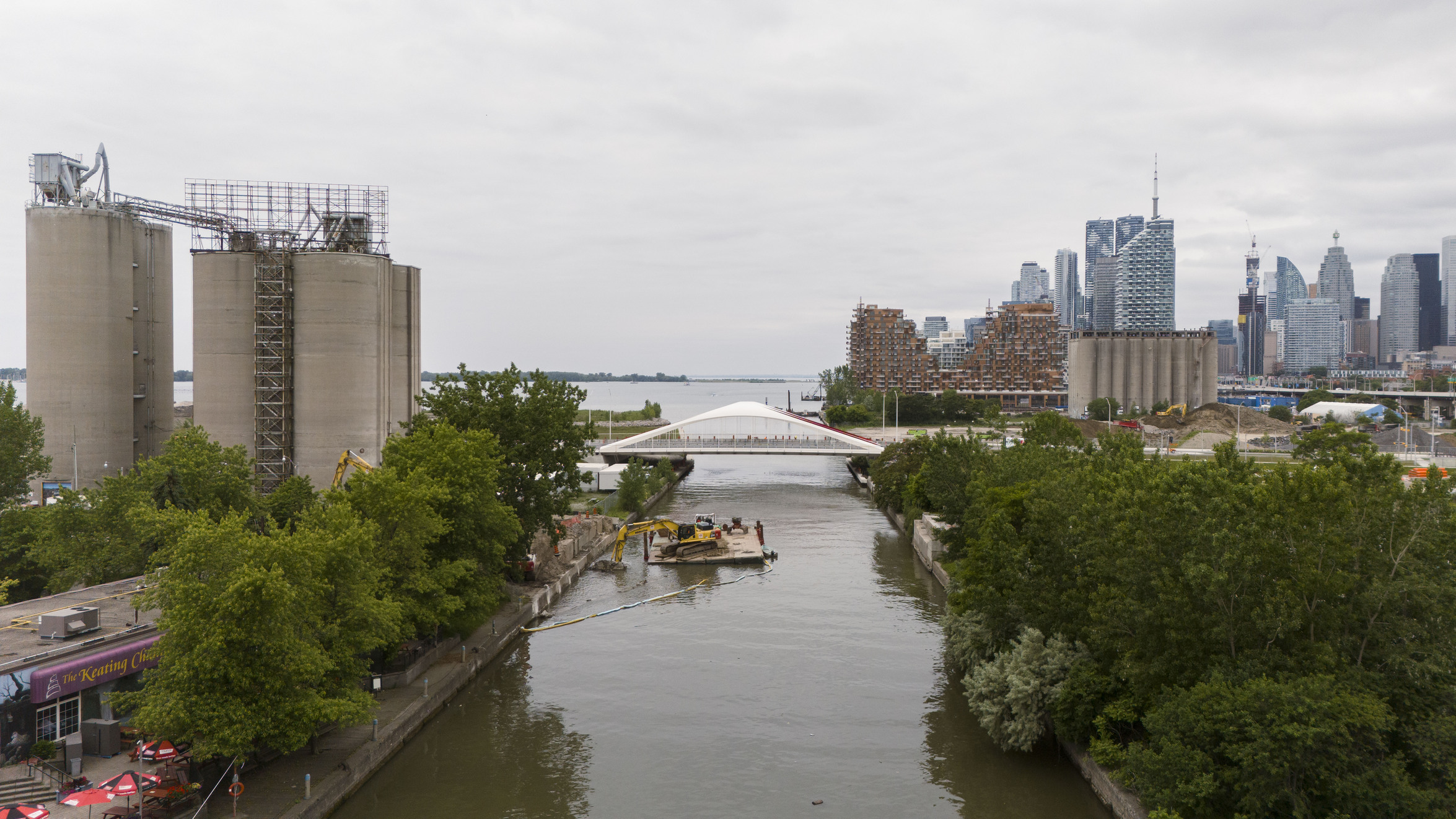

At the mouth of the Don River, which flows into Lake Ontario on the east side of downtown Toronto, a massive push to correct a mistake that’s over a century old is nearly finished.

Hundreds of years ago, the place where the Don reached the lake was a great marsh, teeming with fish and migratory birds, absorbing water to mitigate floods and filtering whatever flowed through. As settlers urbanized what is now called Toronto in the 1800s, displacing Indigenous communities, they also dumped massive amounts of manure — at one point, 80,000 gallons (nearly 303,000 litres) per day — and sewage into the wetland. Before long, the rich biodiversity was gone and the marsh was a stinky public health risk, raising fears of cholera.

In the 1890s, the city dredged the northern edge of the marsh to create the Keating Channel, which would eventually re-route the Don River into an unnatural 90-degree turn into Toronto’s inner harbour. In the 1910s, the newly-created Toronto Harbour Commission decided to drain the marsh and fill it — with a mix of sand, gravel, clay and construction debris like glass, brick, concrete, wood and charcoal — to create new land. It would be used for an industrial district in the Port Lands, leaving a legacy of contamination.

These decisions came with steep consequences not just for wildlife and biodiversity, but also for floods and people. With the flood-mitigation properties of the marsh lost and the river taking an unnatural path, heavy rains and snowmelt began running over into roads and neighbourhoods near the river. The costliest was July 2013, when an intense storm made rivers spill into basements and onto roadways, leaving drivers to wade through waist-high water. In the Don Valley, 1,400 passengers were stranded on a water-filled train for hours — a video of the incident showed a snake sliding between the seats, and they eventually had to be rescued in inflatable boats. The disaster cost $1 billion in insured damage. Similar events are set to happen more often and more intensely as the effects of climate change worsen.

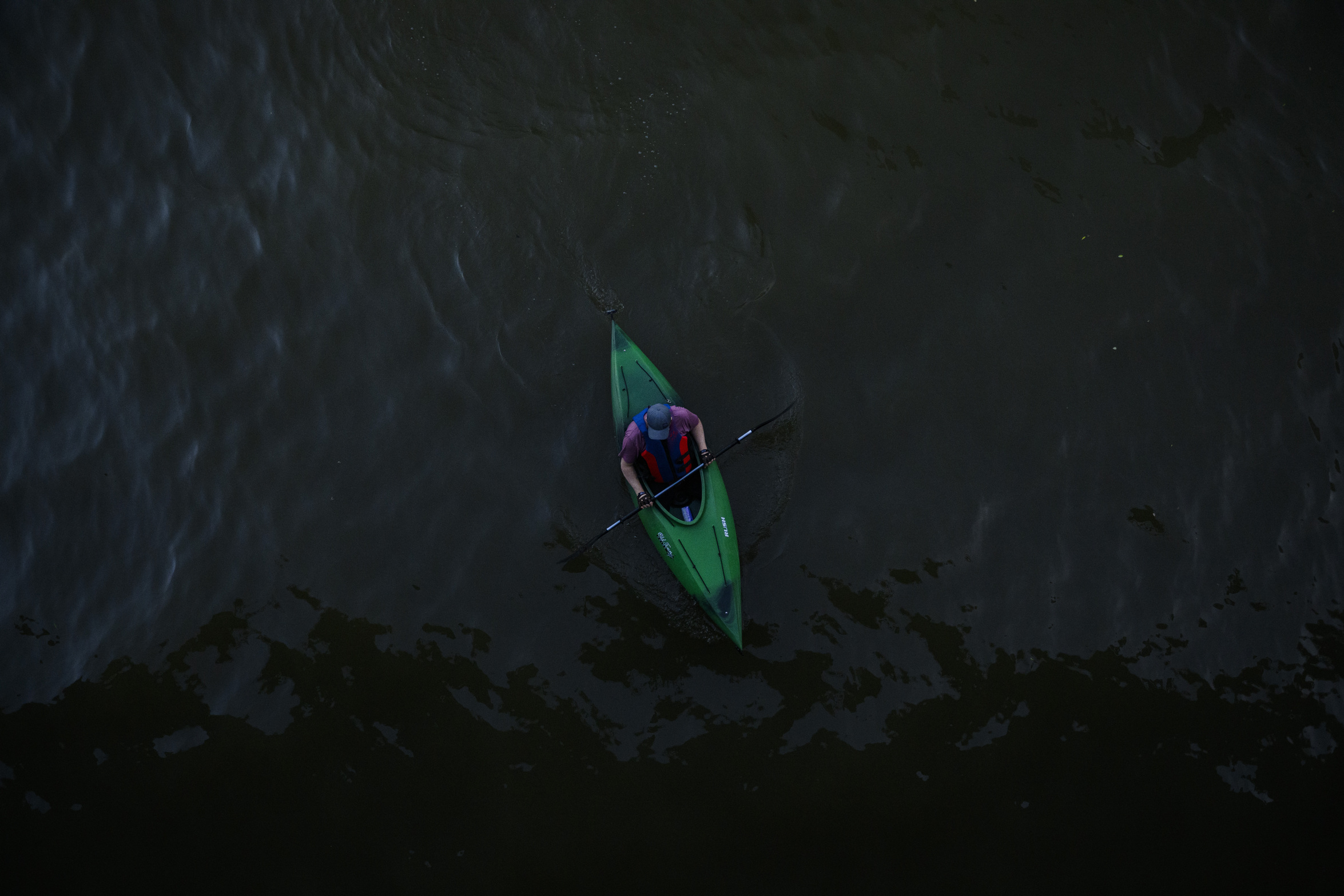

Governments started working on a plan to re-naturalize the mouth of the Don in 2005, a process that inched along until construction began in 2017. It includes a more natural opening for the river, which means the Don will now have two paths to drain into Lake Ontario. It also includes a new 1.3-kilometre river valley to act as a floodplain, and new wetlands, both of which will absorb more water and naturally filter it. The green space will include over two million plants. In the end, the hope is that the area will be a hub for outdoor recreation and the site of a future neighbourhood.

It’s an enormous construction project with a price tag to match: $1.354 billion, just over both its original budget of $1.25 billion and the cost of cleaning up the 2013 floods. All three levels of government — the City of Toronto, the province and the federal government — pitched in.

Waterfront Toronto estimates the project will contribute $4 billion to the Canadian economy and create jobs for up to 30,000 people. It also says the work will save even more money by preventing or lessening future flood events.

Earlier this year, water began flowing into the new river valley. It’s set to be connected to Lake Ontario later in 2024, as long as a leak in one of the plugs separating the bodies of water doesn’t derail the process. Work is ongoing in the Port Lands, which still look like a barren construction zone. It’s set to open in spring 2025, about a year later than its original target.

Nature has inherent value, but how does that translate into actual money? Hamilton, Burlington and the Conservation Halton aimed to answer that question in 2022 by settling on a dollar figure for the worth of Grindstone Creek, a watershed that winds through those municipalities, west of Toronto. The creek flows through the Royal Botanical Gardens in Burlington and a bit of the Greenbelt, before emptying into Hamilton Harbour.

The local governments teamed up with the non-profit Natural Assets Initiative on the project, along with the Royal Botanical Gardens, Conservation Halton and the Greenbelt Foundation. In the end, the groups concluded Grindstone Creek provides $2 billion of value every year just by lowering local flood risk. If the watershed were to vanish, it would cost that much to replace its absorption and filtering functions with human-made infrastructure. The report used a body of existing research to pin down the rough value per square metre of various habitat types for stormwater management: $65 for forests, $200 for swamps, $203 for marshes and $324 for open water.

The $2 billion figure doesn’t include all of the creek’s costs or value. Maintaining natural ecosystems isn’t free, the report notes, though it generally costs more to maintain constructed infrastructure. Ontario municipalities pay an average of $3 billion per year to maintain stormwater pipes, ditches and culverts, according to a 2022 report from Ontario’s arms-length Financial Accountability Office, and climate change is expected to magnify that number over time.

Plus, the group found, Grindstone Creek delivers another $34 million in benefits every year thanks to the role it plays in recreation, habitat biodiversity, lessening air pollution, controlling heat waves, mitigating the effects of climate change and erosion control — Burlington is budgeting $300,000 to create a new, vegetated bank on another creek to prevent erosion there.

The figures aren’t a perfect or complete picture, but they can help governments make decisions about how to use and conserve nature, the groups said.

“Although we can’t reduce nature to a simple dollar figure, this shows the enormous financial value of services communities are getting from nature,” Roy Brooke, the executive director of the Natural Assets Initiative, said in a press release announcing the findings.

“Protecting these assets avoids taxpayers getting stuck with a far higher bill to replace services that nature gives us already.”

The Ontario government pours millions of dollars, year after year into conserving and restoring Great Lakes ecosystems. Back in 2010, the province’s Environment Ministry commissioned a study looking at the economic benefits of those investments, and whether they were panning out.

The report focused on three groups of watersheds around Lake Ontario: the Credit River and 16 Mile Creek west of Toronto, the area around the city itself and Prince Edward Bay to the east. The benefits of securing and restoring land far outweighed the costs, the researchers found. The extent of that varied by area — the benefits of restoring wetlands, for example, were significantly higher in Toronto, where there are few natural wetlands left and a high population, than in less-developed Prince Edward Bay.

The most significant finding, the report said, was that “there are positive economic returns on restoration and protection” of all the habitat types studied.

South of the border, the United States Environmental Protection Agency just published the results of an audit examining whether the US$3.7 billion it has put towards restoring habitats around the Great Lakes was money well spent. It was mostly a success, the audit found: the funds went to groups whose efforts helped protect habitats, cut pollution and tackle invasive species. The main downside was the work didn’t benefit everyone — very few of those groups prioritized environmental justice, or making sure their efforts helped marginalized communities who disproportionately suffer the effects of pollution and climate change.

The 2010 provincial report warned its findings should be taken with a grain of salt given its scope was limited to a few areas and ways of measuring monetary benefit. The body of research used to assign value to nature has grown in the years since — the new guide from the Natural Assets Initiative for assessing the value of ecosystems includes more, and more complex factors, such as how connected animals’ habitats are to other natural areas, or the diversity of species living there. Both things can be used as an indicator of how well an ecosystem is functioning, and therefore, how much monetary value it holds.

What hasn’t changed is an observation made in the 2010 report — the Great Lakes hold another kind of inherent value, one that comes from the knowledge that their ecosystems will be protected for future generations.

“People have demonstrated willingness-to-pay to protect or improve areas that are of no direct use to them, simply for the benefit derived from knowing these areas exist in their natural ecological state,” the report said.

Updated June 28, 2024 at 4:05 p.m. ET: This article was updated to correct the name of the Natural Assets Initiative.

Updated July 25, 2024 at 2:20 p.m. ET: This article was updated to correct that Conservation Halton, not the Regional Municipality of Halton, was involved in the effort to assess the value of Grindstone Creek.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On March 17, federal Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre...

Continue reading

An internal document obtained by The Narwhal shows how the natural resources minister was briefed...

Notes made by regulator officers during thousands of inspections that were marked in compliance with...

Racing against time, dwindling habitat and warming waters, scientists are trying to give this little-known...