Ontario is killing its Endangered Species Act. Here’s what you need to know

After a series of cuts to the once gold-standard legislation, the Doug Ford government is...

The 3,000-hectare McClelland Lake wetland complex was considered too special to dig up.

Then an energy company found one billion barrels of oil under it.

The wetland complex, 90 kilometres north of Fort McMurray, Alta., is a soggy and wildlife-rich area of interconnected wetlands and an important stopover for migratory birds. It’s also a major carbon sink, the result of thousands of years of buildup of peatlands.

When TrueNorth Energy Corporation, a subsidiary of Koch Industries, obtained leases in the area in 1998, it was forbidden to dig up a portion of those holdings. Koch Industries is a privately held conglomerate based in the U.S. still run by one of two controversial billionaire brothers.

A legally binding document known as a sub-regional plan had put the unique lake and surrounding wetland off limits to oilsands mining in 1996, but by 2002 the provincial cabinet had changed the plan after TrueNorth asked for a relaxation of the rules.

Half of the wetland was suddenly fair game for open-pit mining.

Later that same year, the Energy and Utilities Board, which oversaw the energy industry in the province and was a predecessor to the current Alberta Energy Regulator, officially approved TrueNorth’s Fort Hills oilsands project.

“The board has weighed the benefit of recovering the bitumen underlying the [McClelland Lake wetland complex] against the direct environmental impacts and has concluded that in the broader context, it is in the public interest to approve mining within the [wetland], subject to establishing the appropriate mitigation plan,” it wrote in 2002.

TrueNorth itself never developed that plan, which had to ensure the protection of the unmined portion of the wetland ecosystem. It sold its holdings to Fort Hills Energy — majority owned by Suncor — and the Calgary-based oilsands giant came up with a novel scheme. It would build a wall over 10 kilometres long through half of the weltand, cutting off the protected area from the mineable one.

That operational plan was approved by the Alberta Energy Regulator late last summer.

Debate about the ability of the company to carve a wetland in half while ensuring the protection of the remaining portion and the lake have persisted for years. Concerns about groundwater contamination, restricted water flow and the impact on plants and animals that thrive in the unique ecosystem were raised as far back as 2002.

Now a review of the operational plan commissioned by the Alberta Wilderness Association goes further, calling into question everything from the early stages of the design to the need for decades of faultless operation, to the veracity of the modelling around which many of the plans are built.

The organization wants approval of the plan overturned.

“We’ve been calling it, internally, a water management experiment more than a mitigation plan,” Phillip Meintzer, a conservation specialist with the wilderness association, says.

The area around the western portion of the McClelland Lake wetland is now largely barren. Excavators are busy at work. In the working portion of the Fort Hills mine, giant dump trucks are already carting bitumen to be processed.

The tail end of Highway 63, clogged with semi-trucks and busloads of workers, runs through a portion of Fort Hills. Hidden from the road are the McClelland Lake wetland.

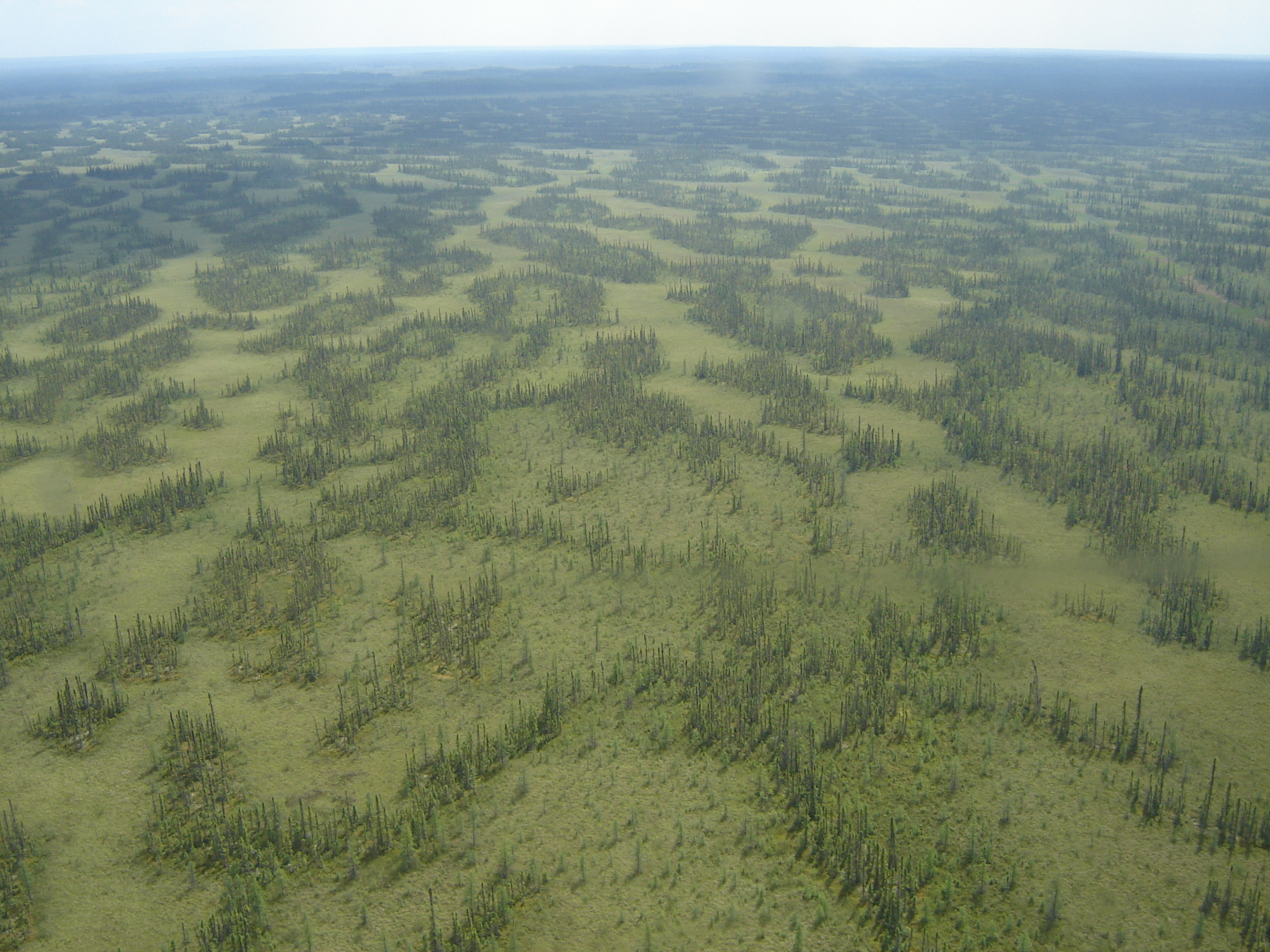

Viewed from above, the fen is a leopard-print expanse of wetland, woods and sinkhole lakes that stretch out from the western edge of the water. It’s a stopping point for birds on the migratory route through the tailings ponds and mines of the Athabasca region, including sandhill cranes, yellow rails, black terns and short-eared owls. Whooping cranes, long endangered, have been spotted, but don’t nest in the area.

Rare plants nestle into the permeable, wet landscape, alongside the abundance of animal life. The peat, like peat throughout the world, stores an astonishing amount of carbon that has built up over thousands of years of wetland formation — an ecosystem impossible to replicate once disturbed.

The original 1996 draft of the sub-regional plan — altered by the provincial government in 2002 — specifically barred surface mining of oilsands in the McClelland Lake wetland ecosystem, but even after the government intervened to allow TrueNorth to mine part of the ecosystem, the plan expounded on the area’s importance.

“A number of specific sites within the [resource management area] warrant some degree of protection or mitigation from the effects of development,” it reads today.

“The most notable of these is the upland area at Fort Hills that Alberta Parks considers to be suitable for a provincial park. This area, the adjacent McClelland Lake wetland and the Bitumount historic site provide significant opportunities for heritage appreciation as well as recreation and tourism.”

The same document lists the patterned fen as a “provincially significant” natural feature.

Suncor plans to start digging in the area around the McClelland Lake wetland in 2025, but the details of how exactly the wall and associated pipes and pumps will work haven’t been finalized.

What is known is that Suncor will build a wall deep into the ground to both protect the unmined portion of the fen and to keep water from the protected wetland away from its mine. Pipes carrying water to and from the wetland will theoretically maintain water levels and chemistry balance.

Seepage pumps and monitoring wells will be used to keep an eye on the impacts of the wetland. The regulator, according to its letter of authorization for the plan, expects any problems should be detected within the first one or two years of operations.

Lorna Harris is the program lead for the Wildlife Conservation Society’s program focused on forests, peatlands and climate change, and specializes in the kind of saturated earth that surrounds McClelland Lake.

She’s one of two reviewers who examined Suncor’s operational plan and shared their findings with the Alberta Wilderness Association.

“The first thing is that half of the peatland is going to be destroyed,” she says when asked about the big picture impacts.

Harris, along with fellow reviewer Kelly Biaggi, a hydrology expert and assistant professor at Brock University in St. Catharines, Ont., highlighted seven key concerns when it came to protecting the unmined half of the wetland, ranging from potential saline contamination to lack of modelling for potential groundwater quality impacts to unrecognized impacts from digging up carbon stores and the resulting carbon pollution.

“We can’t get back the carbon stored within that ecosystem. We can’t get back the habitat, the biodiversity. It is irrecoverable within our lifetimes,” Harris says.

“When something takes thousands of years to develop and it can be lost within a few days of construction, companies often propose that they can restore and reclaim,” she says. “But there is no evidence of anyone anywhere in the world being able to recreate a peatland of this type to the same quality anywhere.”

She says the design of the wall is still in the conceptual stage in the operational plan approved by the Alberta Energy Regulator, so it’s difficult to assess the impact it will have on the wetland and lake. Given recent news about retaining wall leaks in the oilsands, she questions whether anyone can guarantee this wall also won’t fail.

Of particular concern for Harris is saline water infiltrating wetland. If you throw off the chemistry, she says, the wetland could be fatally impacted.

The authors also note modelling only used two to three years of observational data, with predictable eventssuch as the annual spring melt referred to as a “parameter of uncertainty.” It also doesn’t account for wet and dry cycles over decades, which are typical of the area.

“We are concerned that many of the predicted changes to the water table and/or water levels are assumed to have negligible impacts, but without any associated justification provided for why that is assumed to be the case,” they write in the report.

The Alberta Energy Regulator says approval of the operational plan is not the end of its regulatory oversight and that it can still change or revise the plan or modify the conditions regulating the project if deemed necessary.

The wall design, for example, will have to be approved by the regulator prior to construction.

“The [Alberta Energy Regulator] requires Fort Hills to conduct further monitoring, modelling and engineering studies, with performance reports submitted to the [regulator] for review,” Teresa Broughton, a spokesperson for the regulator, wrote in an email to The Narwhal.

“Subject matter experts will continue to be involved in the review of the performance of the project and operational plan and have the mandate to enforce the conditions of the authorizations,” she added.

The regulator says failure to protect the unmined wetland, as stipulated in the company’s Water Act approval, would result in “enforcement action” which could include “modifying or halting operations if required.”

Broughton said there has been significant work put into the operational plan since 2006 and that it incorporates Traditional Knowledge from local Indigenous communities as well as the advice of experts and scientists.

The Alberta Wilderness Association asked for the approval to be overturned, and Broughton said the request will move through the regulator’s reconsideration process, which is outlined in the province’s Responsible Energy Development Act.

Suncor did not respond to a request for an interview.

Meintzer with the Alberta Wilderness Association says his organization has been working to protect the wetland ecosystem for decades. He knew they had to have a close, hard look at the operation plan put out by Suncor.

The trick was finding researchers with a specialization in peatlands and industry impacts who could provide independent opinions.

“There are some very high-profile wetlands experts that helped in the creation of Suncor’s operational plan,” Meintzer says.

“We know that because I went to, I think, almost 25 different people over the course of six months to try and find anyone who didn’t have contractual ties or conflicts of interest with energy companies.”

He says it was important to have experts review the dense plan, stretching to almost 2,000 pages, because it felt like a case of industry thinking it can “technology our way out of this.”

But he says he was surprised by how many concerns were raised by the researchers in a short span of time.

“It’s very explicit that the ecosystem diversity and function in that non-mined side has to be maintained,” Meintzer says of the company’s Water Act approval. “The operational plan has to essentially guarantee that, and the review we had done just raises too many questions for us to say without a reasonable doubt that yes, Suncor’s operational plan is rock solid here.”

Updated on May 1, 2023, at 4:35 p.m. MT to correct a reference to the date Suncor plans to start mining in the McClelland lake wetland complex. The most recent projection is 2025, not 2027 as was previously stated in one instance.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. When I visited my reserve, Moose Factory,...

Continue reading

After a series of cuts to the once gold-standard legislation, the Doug Ford government is...

The BC Greens say secrecy around BC Energy Regulator compliance and enforcement is ‘completely unacceptable’

Boil-water advisories in Moose Factory, Ont., are frequent, expensive and ongoing — but not ‘long-term’...