Rocky Mountain coal mine in Alberta takes next step to expansion

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

If the Alberta Wilderness Association wanted to provide feedback on a controversial plan to cut a sensitive wetland in half for the sake of mining bitumen, it should have joined a Suncor sustainability committee created to support the project.

That’s according to one portion of a recent submission from the oilsands giant to the Alberta Energy Regulator.

The association has pushed the regulator for a reconsideration of the company’s plan to build a wall more than 10 kilometres long through the McClelland Lake wetland complex in northern Alberta. It enlisted two experts to review Suncor’s operational plan, which was approved by the regulator late last summer.

Those experts raised concerns ranging from potential saline contamination of the wetland to lack of modelling for potential groundwater quality impacts, and unrecognized impacts from digging up carbon stores and the resulting carbon pollution.

Suncor, in a letter to the regulator on May 31, appears to have little patience for the request and the association’s submissions.

“The Alberta Wilderness Association has ample opportunity to participate in and contribute to the works of the sustainability committee and it unilaterally and deliberately chose not to participate in that process,” Michael Robinson, manager of regulatory approvals for Suncor Fort Hills mine, wrote on behalf of the company.

“It refused to be a part of the sustainability committee where it would have benefited from hearing the views of all the participating parties.”

The association has said the committee — a Suncor entity created to provide feedback on environmental and social concerns, including Traditional Knowledge — is a means to “legitimize the wetland complex’s destruction.”

The Calgary-based company also argues the Alberta Wilderness Association should have pursued other appeal options — although none are available to the organization. It says the information provided by the association in response to its plan is not new and therefore doesn’t warrant a reconsideration, and calls into question the veracity of the scientific objections levelled against the operational plan.

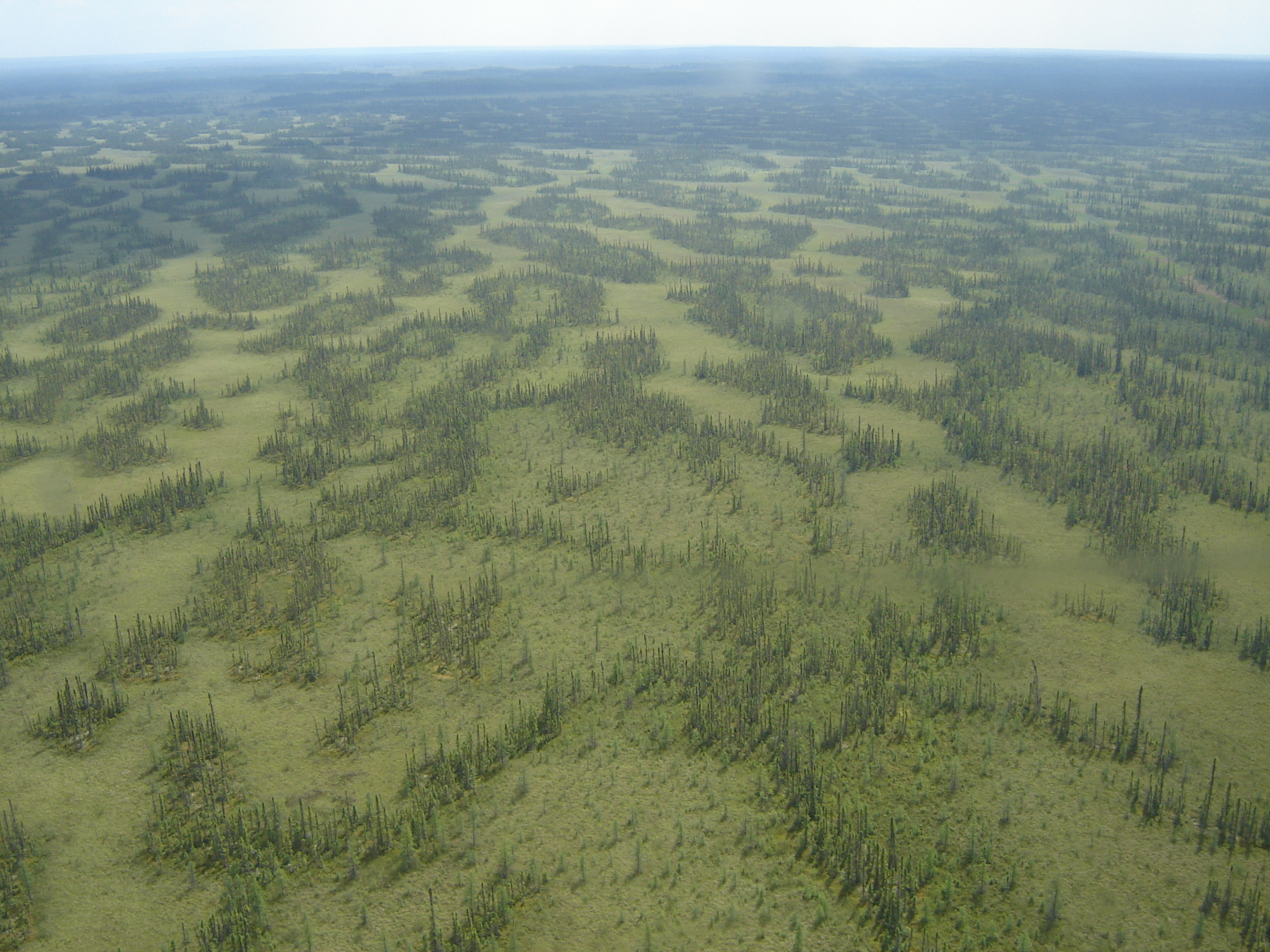

The McClelland Lake wetland complex is a sprawling mix of woods and sinkhole lakes that stretch out from the western edge of the lake. It’s a stopping point for birds on the migratory route through the tailings ponds and mines of the Athabasca region, including sandhill cranes, yellow rails, black terns and short-eared owls. Whooping cranes, long endangered, have been spotted, but don’t nest in the area.

Rare plants nestle into the permeable, wet landscape, alongside the abundance of animal life. The peat, like peat throughout the world, stores an astonishing amount of carbon that has built up over thousands of years of wetland formation — an ecosystem impossible to replicate once disturbed.

The area was once recommended for protection from oilsands mining, but that protection — laid out in a legally binding sub-regional plan — was overturned by the Alberta cabinet in 2002.

Suncor’s Fort Hills mine — which made headlines this spring after it illegally released six million litres from a sediment pond into the Athabasca River — is now slowly but surely encroaching on the wetland area and will soon surround and consume the western half of it. Approval of the mine, which happened shortly after cabinet reversed protection more than 20 years ago, was contingent on the company leaving the other half of the wetland unharmed. That’s the source of the current debate.

The operational plan approved by the regulator calls for a wall through the complex, complete with pipes and pumps in order to both protect the unmined portion of the wetland and the mine on the other side.

The Alberta Wilderness Association, however, says the plan is based on flawed data, underestimates the risks involved and can’t guarantee protection of the unmined portion of the wetland.

Any adverse effects won’t be known until mining is underway and then it’s too late, according to the association.

In addition to its initial review, the association released three new critiques of the Suncor Fort Hills operational plan in response to the company’s letter to the regulator. The critiques note further concerns about the impacts of strip mining the area, including increased risk of wildfires due to changes to the hydrology of the site.

“We stand by the fact that there are glaring omissions,” Phillip Meintzer, a conservation specialist with the wilderness association, says.

“That’s the crux of our argument.”

Suncor did not respond to The Narwhal’s requests for an interview on the reconsideration or the company’s letter repudiating it.

Its response to the association’s request rests largely on arguments around processes, its own committee and the science behind the association’s review.

It argues the reconsideration process should not and, in fact, cannot be requested by outside organizations or individuals, and can only be initiated by the regulator itself. There is nothing in Alberta’s Responsible Energy Development Act, however, to prohibit a request.

Suncor also says there are other avenues to pursue, such as appealing the decision through the regulator, but that requires a person to be directly impacted, which doesn’t apply to the organization.

The other appeal process — going through the Alberta Court of Appeal — has a tight timeline of one month to file, which wasn’t possible given the regulator did not notify the public that the plan had been approved. It also requires that the decision in question erred in law or jurisdiction, neither of which are being contested by the association.

“If parties were permitted to request reconsideration of the Alberta Energy Regulator decision when they please, there would be no finality to the Alberta Energy Regulator decisions,” writes Robinson, arguing this would add “significant uncertainty in the regulatory process.”

Robinson says it took the association far too long — seven months — to respond to Suncor’s plan and says there is no new information in the association’s request, which is a critical component in instigating a reconsideration.

Suncor argues the experts engaged by the Alberta Wilderness Association erred in their review of the operational plan when they said there were still serious outstanding questions regarding the impact of the project.

At one point, the oil giant criticizes the organization for using data from impacts on other wetlands in the oilsands region to bolster the argument against mining the McClelland Lake complex. Suncor says there should be evidence of impacts to McClelland.

Those impacts do not yet exist because the mining hasn’t started.

But the company believes it has done the work to ensure protection of the unmined portion, and insists it has appropriate monitoring and mitigation strategies in place if impacts are detected in the complex.

Suncor “submits that the Alberta Energy Regulator should decline to exercise its extraordinary power of reconsideration, and requests that the [regulator] dismiss the Alberta Wilderness Association’s request without further process,” Robinson writes.

Meintzer says Suncor fails to address the concerns raised by the experts it enlisted to review the plan: Lorna Harris, the program lead for the Wildlife Conservation Society’s program focused on forests, peatlands and climate change, and Kelly Biaggi, a hydrology expert and assistant professor at Brock University in St. Catharines, Ont.

“It’s more around process than it is about the substantive sort of evidence we provided in our report,” he says.

“I always try to refocus that the operational plan should be bound by the conditions that were set when this was all permitted back in the day, and that says the operational plan itself has to demonstrate it can guarantee that the unmined half is not going to be harmed.”

He argues there is significant new information for the regulator to consider in its previous critique of the operational plan and new critiques included in its response to Suncor, submitted on June 9.

None of that information could be submitted prior to approval of the plan or within tighter timelines given the association’s small budget, limited staffing and the complexity of the operational plan.

Meintzer says Suncor was responsive to questions from the association and did offer further consultation, but only through the company’s own sustainability committee, which would likely limit the association’s ability to speak publicly on the project and concerns.

Being involved in the committee also provides tacit approval of the plan to mine half of the wetland.

“Our mandate is to defend these wilderness spaces,” he says. “It doesn’t feel appropriate for us to be in a process that enables harm.”

The regulator’s reconsideration process isn’t well known. The Alberta Wilderness Association has never used it and isn’t entirely sure how it will play out. Meintzer says others he’s spoken to in the environmental sphere aren’t sure either.

The Alberta Regulator lists 24 instances of reconsideration requests, four of which were granted. Ten of the reconsiderations were of approvals for coal projects after the province reversed its plan to allow mining in the Rockies.

Section 42 of the Responsible Development Act, which authorizes reconsiderations, is short and only says these types of reviews are at the discretion of the regulator.

Karen Keller, a spokesperson for the regulator says there is no timeline for this process and the organization will review the submissions from Suncor and the Alberta Wilderness Association before determining whether to proceed.

“If we do exercise our discretion to proceed to reconsider the operational plan, the [regulator] will communicate the applicable timelines and process that will be followed for the reconsideration, as well as whether the reconsideration will be conducted with or without a hearing, as per section 43 of the Responsible Energy Development Act,” she said by email.

But there aren’t many options open to organizations like the wilderness association or individuals who want to challenge a project like the expansion of the Fort Hills mine into the wetland.

Suncor’s own submission to the regulator shows there are no alternative avenues of appeal, something Meintzer says is common in Alberta.

Limiting appeal largely to those directly affected by a project due to adjacent property or land rights ignores the nature of these kinds of developments and their global climactic impact, Meintzer argues.

“We see this right now with people in New York dealing with the smoke from Canadian wildfires,” he says.

“It’s like, they’re being directly and adversely affected by the stuff that’s going on here.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. A $335 million funding commitment to fund...

Continue reading

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

A trade war could help remake B.C.’s food system, but will family farmers be left...

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...