Ontario’s public service heads back to the office, meaning more traffic and emissions

For 15 years and counting, my commute from Mississauga to Toronto has been mired by...

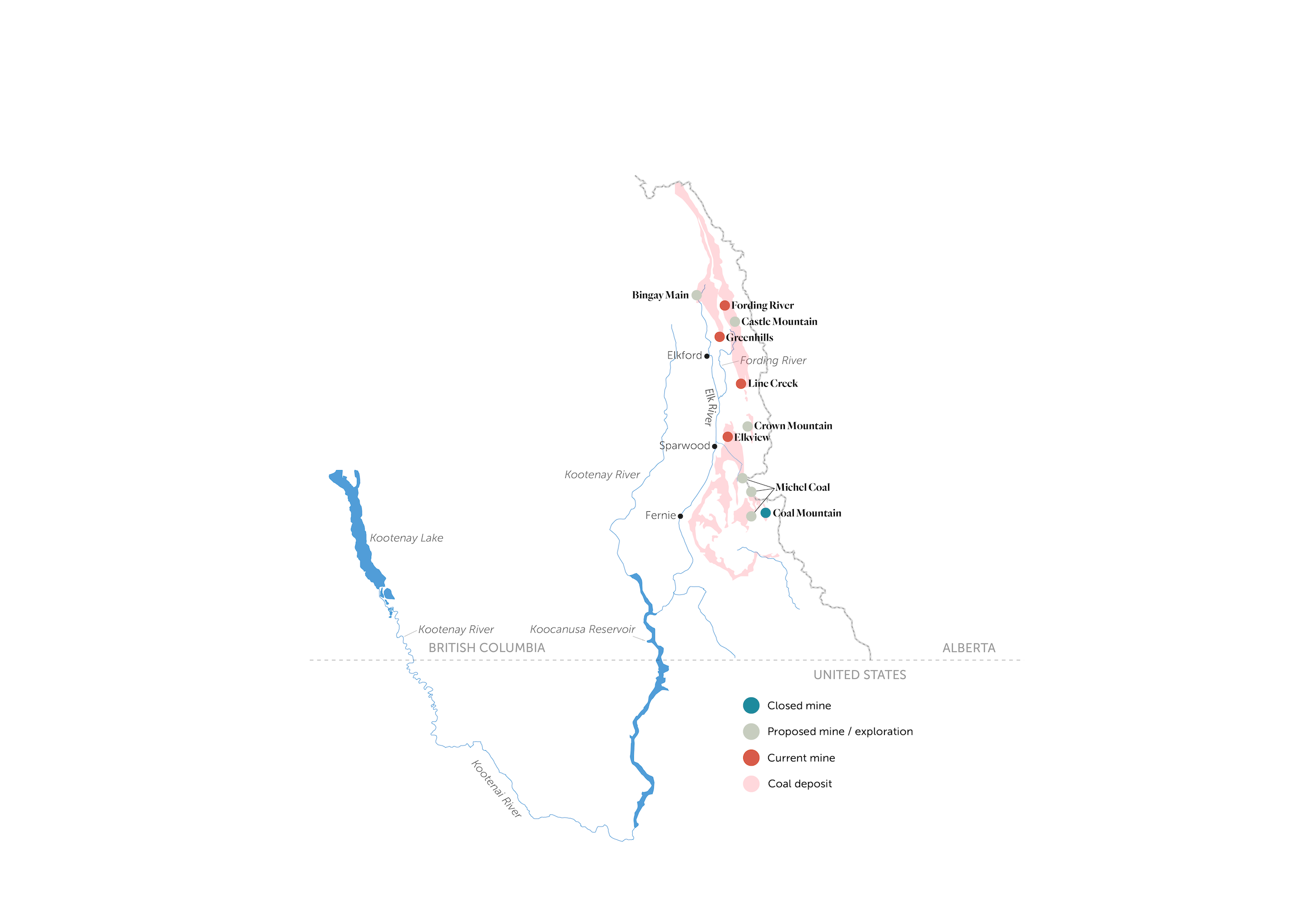

For more than a century metallurgical coal, used to make steel, has been mined from the mountains in southeastern B.C. As the piles of rock left over from the mining process grew, so did concerns about pollution.

Contaminants from the mines owned by Teck Resources travel through rivers in the Elk Valley to Lake Koocanusa, a cross-border reservoir, and into the Kootenai River, flowing through Montana and Idaho, threatening fish and other aquatic life. It’s a source of contention between Canada and the U.S.

But the two countries have an agreement meant to tackle issues exactly like this: The Boundary Waters Treaty.

Signed in 1909, the treaty created the International Joint Commission to investigate and make recommendations to resolve disputes when asked. In the intervening years, the commission has been called on to study pollution in Lake Erie, flooding in the Red River basin and water quality in lakes Champlain and Memphremagog. But it’s never been called on to investigate coal mining pollution from southeast B.C. — not for lack of trying.

Since 2012, the Ktunaxa Nation Council, Kootenai Tribe of Idaho, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, all part of the transboundary Ktunaxa Nation, have repeatedly called for the Canadian government to ask the International Joint Commission to scrutinize and recommend solutions to the contamination from coal mines. Their calls have been echoed by environmental groups, Montana’s Department of Environmental Quality, U.S. Senator for Montana Jon Tester and even the joint commission itself.

But, in late April, a spokesperson with Global Affairs Canada told the Ktunaxa Nation Council, which represents four First Nations in southeast B.C., that the government had decided against involving the International Joint Commission.

Evelyne Coulombe, the executive director of U.S. Transboundary Affairs at Global Affairs Canada, wrote in an email that it had been “decided that [International Joint Commission] involvement was not the best route at this time.”

“[It] was a blatant disregard for Canada’s legal duties to our four First Nations, not to mention complete disrespect for our four First Nations’ decision-making and governance authority,” Nasuʔkin Heidi Gravelle of the Yaq̓it ʔa·knuqⱡi‘it, one of four Ktunaxa Nation Council communities, told The Narwhal.

Ktunaxa Nation Council was outraged, and said so in a May 6 letter to Foreign Affairs Minister Mélanie Joly and Environment and Climate Change Canada Minister Steven Guilbeault.

“We are stunned that Canada can, in this day of reconciliation and public vows by the prime minister to fully implement the [United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples], commit such a disrespectful act,” the letter said.

After a decade of pushing for the International Joint Commission to be involved, Ktunaxa Nation wasn’t about to give up.

“Ministers, we do not accept this outcome. This decision has trampled on our rights and disrespected our Nation. We call on you to direct your staff to reverse this decision, and recommit to consent-based engagement on a joint [International Joint Commision] reference,” the Nation wrote to Joly and Guilbeault in May.

The following week, the commission itself wrote to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and President Joe Biden alerting them that the issue is covered by Article IV of the Boundary Waters Treaty. It states that “waters flowing across the boundary shall not be polluted on either side to the injury of health or property on the other.”

The letter also raised the prospect that the U.S. may move on its own to involve the commission.

“We understand the United States government is discussing the merits of a unilateral reference to the [International Joint Commission] on this matter. While we would accept and act on such a reference, as prescribed in the treaty, we believe it is in the best interests of all concerned if a joint reference be made,” the commissioners wrote.

Three weeks after the Ktunaxa Nation Council was told Canada wouldn’t back an investigation — facing political pressure from both sides of the border — James Emmanuel Wanki, a spokesperson for Global Affairs Canada, told The Narwhal they might.

“Canada has not rejected the possibility of a reference to the [International Joint Commission] at this time,” Wanki wrote in a statement to The Narwhal. He noted that discussions are ongoing with the U.S. about the transboundary pollution of the Kootenay watershed.

“We take seriously the concerns related to potential downstream impacts from coal mining in the Elk Valley, and the call for involvement of the International Joint Commission,” Wanki said.

“We are committed to continuing to work with Indigenous Nations and the province of British Columbia on a collaborative path forward to address the concerns.”

Hilary Clinton was the U.S. secretary of state and John Baird was Canada’s minister of foreign affairs back in 2012 when the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes and Ktunaxa Nation Council asked for Canada and the U.S. to call for an investigation by the International Joint Commission.

Since then, there have been four new secretaries of state and six new ministers of foreign affairs — and the Indigenous governments are still asking for the same thing.

In the meantime, the water contamination has only gotten worse.

Teck has so far invested more than $1.2 billion in water treatment and other measures to contain the pollution flowing from its mining operations, with plans to ramp up treatment capacity later this year. But water quality data shows concentrations of selenium, an element known to cause deformities and impede reproduction in fish and other wildlife, have increased steadily in the Elk River. It now far exceeds the levels the B.C. government recommends for the protection of aquatic life.

“The overpolluted waterways, which are in our yard, they’re the waterways that feed our fish and our wildlife — that’s our sustenance, that’s how we live and we want to carry those traditional ways into our future generations,” Gravelle said.

“Our Elders, they’ve already been traumatized through the residential school system and assimilation for hundreds of years, but I tell you, when they see that land, they’re being re-traumatized because it’s devastation.”

As the B.C. and Canadian governments consider proposals by Teck and other companies to expand mining in the region, calls for action to address the pollution have become more urgent.

In December, the Ktunaxa Nation Council reiterated its request to the federal government to refer the issue to the International Joint Commission.

“Solutions need to be brought forward and they need to be independent of the political and economic drivers that created the situation — and the [International Joint Commission] does that,” Gravelle said.

Initially, there was some hope that this time might be different. The federal government was developing a “concept paper” for a possible reference to the commission.

But by late April, when they got the email from Coulombe at Global Affairs Canada, that optimism had been quashed. Work on the concept paper was being halted and Canada was not recommending pollution from B.C. coal mines be investigated by the International Joint Commission.

“We have proposed to the U.S. that we explore other ideas to address the concerns, including ways to bring stakeholders and Indigenous peoples on both sides of the border together in an effort to work towards joint solutions to the issues at stake,” Coulombe wrote in that late April email.

The federal and provincial governments have made commitments to reconciliation and to implementing the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, but “to really, really implement those strategies and laws and covenants — the entirety of it — it is so much more than just the people, we need to reconcile with the land,” Gravelle said.

“We’re just trying to do the right thing, and we’re hitting roadblocks, we’re hitting brick walls,” she said.

South of the border, Rich Janssen, head of the natural resources department and member of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, said the Tribal Council was “extremely disappointed” when it heard the Canadian government was refusing to involve the International Joint Commission in this issue.

“We’re not against mining, but we are against mining that continues to pollute our natural waterways or impacts our cultural resources, our wildlife, our fisheries that we’ve used for millennia,” he said in an interview.

Erin Sexton, a research scientist at the University of Montana’s Flathead Lake Biological Station and longtime scientific advisor to the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, said the International Joint Commission offers a table and governance framework for all the affected governments — Indigenous, federal, provincial and state — “to have a conversation about this watershed.”

“What is so scary about having an objective scientific conversation with all the impacted governments at the table? That’s the equitable thing to do with this issue,” she said.

Global Affairs Canada declined The Narwhal’s request for an interview with Joly and did not explain the discrepancy between Coulombe’s email to the Ktunaxa Nation Council and the department’s subsequent statements to media that it had not made a decision whether to involve the International Joint Commission.

The federal government is also working to develop national coal mining effluent regulations, their spokesperson noted, but some observers warn they would do little to solve the problem as currently proposed.

It didn’t come as a surprise to Gravelle that Global Affairs Canada would walk back its decision.

“How shameful does it look that this was denied?” she said. “So, let’s tell everybody we didn’t actually make that decision yet.”

Gravelle said both Yaq̓it ʔa·knuqⱡi‘it and the Ktunaxa Nation Council are expecting a written response from Global Affairs Canada in the coming days and will determine their next steps once it’s received.

But, “at the end of day, actions speak louder than words,” she said.

Enbridge Gas will face Waterloo Region in a hearing before the Ontario Energy Board to renew an agreement that would allow the company to continue...

Continue reading

For 15 years and counting, my commute from Mississauga to Toronto has been mired by...

For our last weekly newsletter of the year, we wanted to share some highlights from...

The fossil fuel giant says its agreement to build pipelines without paying for the right...