The site of an infamous B.C. mining disaster could get even bigger. This First Nation is going to court — and ‘won’t back down’

Xatśūll First Nation is challenging B.C.’s approval of Mount Polley mine’s tailings dam raising. Indigenous...

The adult population of genetically unique westslope cutthroat trout in a river in B.C.’s Kootenay region dropped by 93 per cent this past fall compared with 2017 levels, according to a monitoring report from Teck Resources.

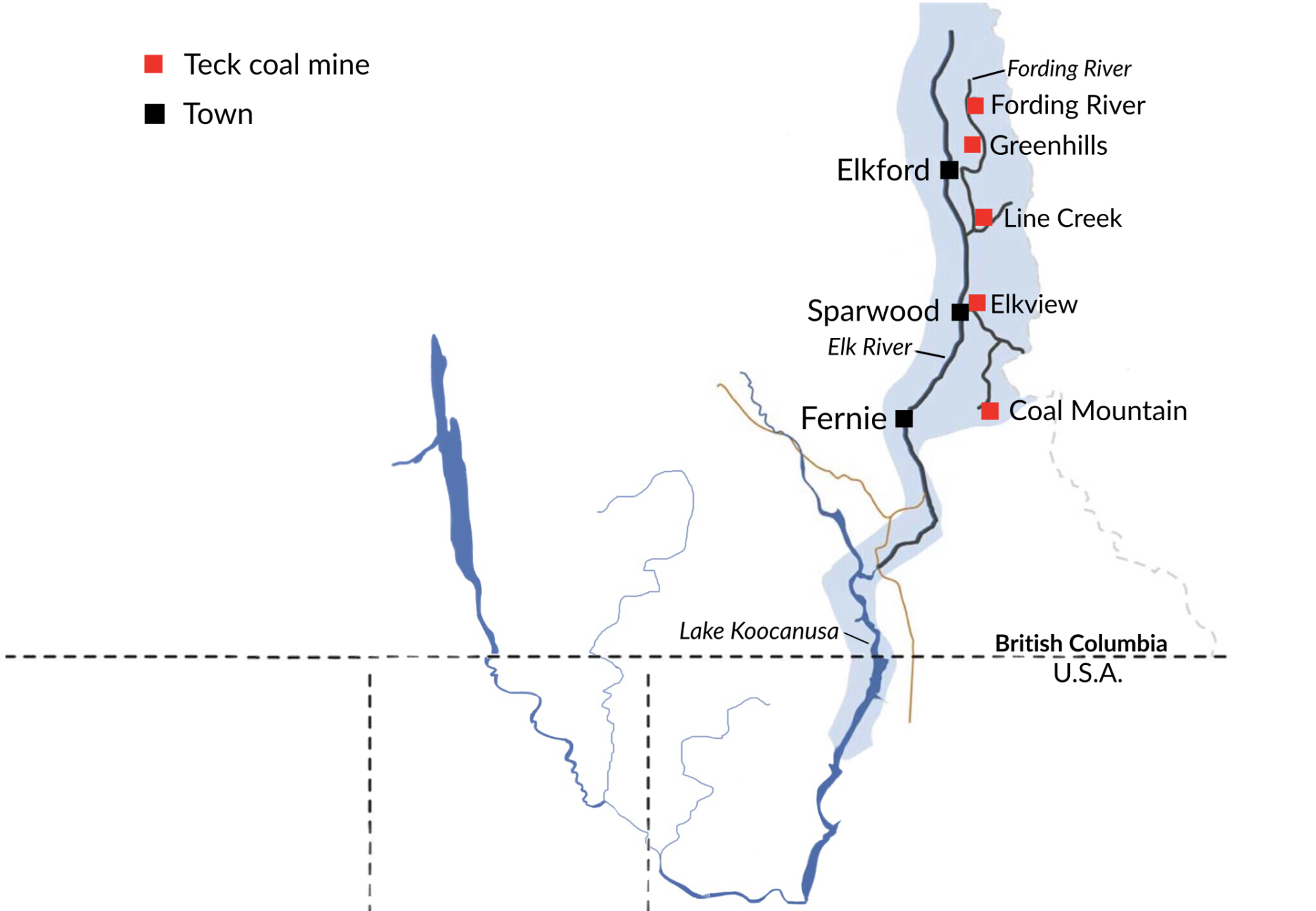

The company operates four giant metallurgical coal mines in the Elk Valley region, where levels of selenium pollution, which originates from the mines’ many waste rock piles, have increased steadily for decades.

Teck has conducted fish surveys in the Upper Fording River since 2012. A fall presentation from Teck reviewed by The Narwhal shows that monitoring conducted by contractors in September and October 2019 identified a precipitous decline in adult and juvenile westslope cutthroat trout in the Upper Fording and that such a decline “represents a trigger” for a population crash.

Upper Fording River adult trout counts dropped 93 per cent and juvenile counts dropped 74 per cent from 2017 levels, according to Teck.

In Harmer Creek, near Teck’s Elkview mine, adult fish counts dropped 26 per cent and juveniles 96 per cent. In Grave Creek, near the Line Creek mine, juveniles declined 25 per cent, but counts for adults increased 25 per cent compared to 2018 counts.

“It’s very significant to see that drastic of a drop in numbers for westslope cutthroat trout,” University of Montana biologist Erin Sexton told The Narwhal. “It’s very unfortunate news.”

Sexton began studying selenium in the Elk Valley in the early 2000s and was involved in a process that led to the creation of the Elk Valley Water Quality Plan. It is under this plan that the province has continued permitting Teck’s mining operations, despite growing selenium pollution.

The plan was informed by a

2014 report prepared for Environment and Climate Change Canada by Dennis Lemley, a renowned selenium expert. The report warned that selenium pollution from mining in the Elk Valley was negatively impacting fish and concluded that increases in selenium pollution would inevitably lead to “a total population collapse of sensitive species like the westslope cutthroat trout.”

Sexton said she was disappointed but not surprised to see Teck reporting the population drop. “It’s déjà vu,” she said.

A meandering bend in the Upper Fording River where high levels of selenium have been measured. Photo: Jayce Hawkins / The Narwhal

Sexton added it is evident B.C. ignored available science when structuring permits for Teck’s Elk Valley operations. Under the Elk Valley Water Quality Plan, the province allows Teck to continue operating its mines as long as the company is working toward a long-term plan to stabilize selenium levels by 2023 and reduce levels after 2030.

“I think for a lot of us who participated in the process to create the plan, it feels like a wasted effort because the province didn’t set any limits that are protective of fish and aquatic life.”

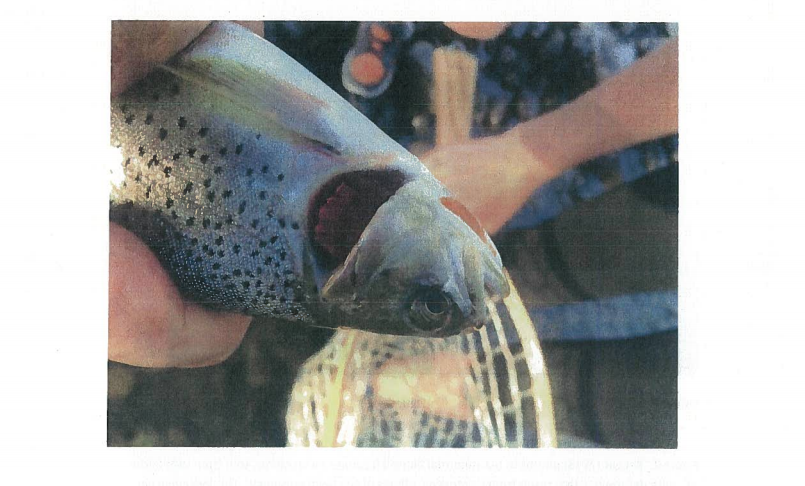

The Elk Valley is a prized spot for fly-fishers, who refer to these unique trout — which have dark freckles, orange gashes along the throat and small teeth lining the mouth — as “cutties.”

Westslope cutthroat trout are only found in a small portion of their original habitat and are thought to be one of the first species to populate B.C. after the last ice age. Pacific populations are listed federally as a species of special concern.

The trout living in the slow-flowing waters of the Upper Fording River are considered genetically distinct because they exist above Josephine Falls, which isolates them from other trout in the Elk and Fording Rivers.

“The Upper Fording is the closest to the biggest mines,” Sexton said, “so it has the highest levels of selenium in the system. As you move away the levels decrease.”

Selenium, a naturally occurring element, is commonly found in coal-rich deposits and is essential to human health

in very small doses. While selenium can be toxic to humans at high levels, even small amounts can be harmful to egg-laying creatures, including fish and birds. In trout it can cause spinal and facial deformities, missing gill plates and reproductive failure.

Westslope cutthroat trout showing spinal deformities. Photo: Environment Canada

A westslope cutthroat trout with a missing gill plate, a telltale deformity caused by selenium poisoning. This trout was caught in 2014 in Coal Creek, a tributary of the Elk River. Photo: Environment Canada

Westslope cutthroat trout exhibiting deformities have been found in the Elk Valley with increasing frequency in recent years.

B.C.’s general water quality guidelines recommend selenium levels be kept to two parts billion to protect aquatic life. Yet in waters throughout the Elk Valley, selenium has been measured at levels higher than 150 parts per billion.

Sexton pointed out the province’s guidelines for daily selenium levels in the Upper Fording River allowed 155 parts per billion in 2014 with an expectation they would be reduced to 71 parts per billion by 2023.

“From a scientific perspective, I’ve never understood how the province of B.C. has been able to set these thresholds for the entire Elk River Valley that are dangerous to fish health,” Sexton said.

“I always say that when I read Teck’s permit, it looks to me like the Elk and Fording Rivers are a sacrifice zone.”

In response to emailed questions, David Karn, a spokesperson for the B.C. Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy, said the province is aware of the recent trout monitoring results and “is concerned about the declines identified.”

Karn said third party consultants are investigating the causes of the declines and Teck is reporting to provincial regulators bi-weekly on the findings and its efforts to limit risk. He added that B.C. is working with other provinces and the federal government to oversee the investigation as well as proposed fish population studies this year.

Chris Stannell, public relations manager for Teck, told The Narwhal the “reasons for the lower fish counts are unknown at this time” and the company has put together a team of external experts to evaluate possible causes of the population crash, including “water quality, flow conditions, habitat availability, predation and other factors.”

“We take this issue very seriously,” Stannell wrote in an email. He said the company has invested $437 million to implement the Elk Valley Water Quality Plan and estimates an additional $649 to $690 million will be invested in the region, in large part for water treatment facilities, over the next five years.

In 2014, Teck introduced the $600-million Line Creek water treatment plant, which caused an accidental fish kill six months after coming online. In 2017, the plant was taken offline after Teck discovered the treatment process was releasing a more bioavailable form of selenium into the environment, meaning it was taken up more readily by biotic life.

Since the plant was recommissioned in 2018, Teck has seen “reductions in selenium concentrations downstream of the operating Line Creek treatment facility,” said Stannell, adding that two more water treatment plants are being built.

Teck’s five metallurgical coal mines are all upstream of the transboundary Koocanusa Reservoir. Map: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

Lars Sander-Green, an analyst with the local conservation group Wildsight, said the population collapse should lead to a change in the way coal mining is done in the Elk Valley. But, he said, that’s far from the case.

“What’s really crazy is even with this massive loss of fish, we still have Teck pushing hard on new mining expansion that would push farther into this river,” Sander-Green said.

Recently Teck began the early consultation process for a major expansion of its Fording River operations, the largest of the company’s mining operations in the Elk Valley. The Castle expansion project would extend the Fording River operations “for decades,” according to a February presentation Teck delivered to the District of Sparwood. According to Teck, the Fording River operations produce 8.5 to 9.5 million tonnes of metallurgical coal for use in steelmaking each year.

“It’s another major expansion but it’s only going to be subject to a B.C. environmental review and not likely a federal review because it’s an expansion and not a new mine,” Sander-Green said.

The proposed expansion comes at the same time as proposals for new Elk Valley mines from three other companies.

“What’s happening with trout suggests things need to change in a big way if we’re going to have fish in that area,” he said. “It creates a lot of concerns about what is going to happen downstream in the long term.”

Concerns across the border have been mounting for several years as the Elk Valley watershed drains into the Koocanusa reservoir, which extends into Montana. Selenium levels are rising in that reservoir.

“This wildlife and these landscapes don’t know political boundaries,” Sexton said.

Teck coal mine in B.C.’s Elk Valley. Photo: Jayce Hawkins / The Narwhal

“I know these things get polarized across international boundaries, but I have a lot in common with people in the Elk Valley and I see it as a shared watershed. I think the U.S. gets pitted against Canada, or Montana against B.C., but I think we should all be being good stewards of our rivers together.”

She added it has been “very complicated and challenging” for U.S. agencies and communities to be collectively outside the decision-making process in B.C., which has permitted increasing mining activity and allowed selenium pollution to grow in the Elk Valley through the decades.

“It creates this complicated environmental challenge for anyone who is a stakeholder in the watershed,” Sexton said, adding there is a frustrating lack of transparency from both B.C. and Teck when it comes to monitoring and sharing raw data.

Canada has no specific, legally binding regulations on the pollution that emanates from coal mines. While such effluent regulations exist for metal mines, specific rules for coal mines have been stuck in limbo for years.

The most recent draft of the regulations proposes two sets of rules, one for all coal mines and another tailored to Elk Valley operations.

The rules proposed for Teck’s mines are weaker as a result of years of lobbying, Sander-Green said.

When asked about those lobbying efforts, Teck’s Stannell referred The Narwhal to a 2018 sustainability report that states Teck “remained actively engaged in the review process for the draft regulations through 2018.”

“For Teck, the final design of these regulations is critical for long-term planning for our steelmaking coal operations in Western Canada. We will continue to participate in the review and dialogue process with the Government of Canada in 2019 to help ensure the regulations are well designed and science based.”

Sander-Green said he thinks the federal and provincial governments are capitulating to Teck.

“B.C. has shown again and again they are willing to sacrifice our clean water and fish for coal mining revenue. We’ve seen that for decades now.”

The province first established a task force to address selenium in the late 1990s.

“Since then problems have been getting worse and worse. A lot of talk but no action,” Sander-Green said.

He said Wildsight is asking for a moratorium on new mining in the Elk Valley.

“We’re in a big hole and we have to stop digging.”

Like what you’re reading? Sign up for The Narwhal’s free newsletter.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. When I visited my reserve, Moose Factory,...

Continue reading

Xatśūll First Nation is challenging B.C.’s approval of Mount Polley mine’s tailings dam raising. Indigenous...

As the top candidates for Canada’s next prime minister promise swift, major expansions of mining...

Financial regulators hit pause this week on a years-long effort to force corporations to be...