The Narwhal picks up four Canadian Association of Journalists award nominations

From investigative reporting to stunning photography, we’ve been recognized with four 2024 CAJ Awards nods...

The first time I met Curtis Rattray, I was going on four hours of sleep and waiting by the luggage carousel in the Terrace airport.

“You Carol?” Rattray asks, looking at my feet in the Terrace airport.

“I could tell by your boots,” he said, gesturing quizzically at my choice of footwear, a relic of my mother’s closet: Stone Ridge hikers, circa 1990 with a strangely high back heel.

Rattray, all arms and legs with a ginger beard and shoulder-length brown hair, hoists my pack onto his shoulder after I drag it like a dead beast from the luggage belt.

Looking much younger than his 57 years, Rattray is a member of the Tahltan First Nation and an experienced backcountry guide who’ll be leading me and three others on a six-day journey through the Spectrum Range.

As we drive five-hours north to Tatogga Lake, Rattray recounts his time as president of the Tahltan Central Council, in the military, trail clearing for B.C. Parks and gives a surprisingly detailed account of the history of naval architectural design and how it intersects with the consumption of fossil fuels. And this is just Day 1.

By the time we’ve reached our destination for the evening, Rattray has used scenes from the films Apocalypse Now, Smoke Signals, Whippet, Working the Curve and Spirit of the Sea to add pop cultural references to his reflections on everything from Indigenous identity to the struggles of adolescence to his aversion to purchasing store-bought salmon.

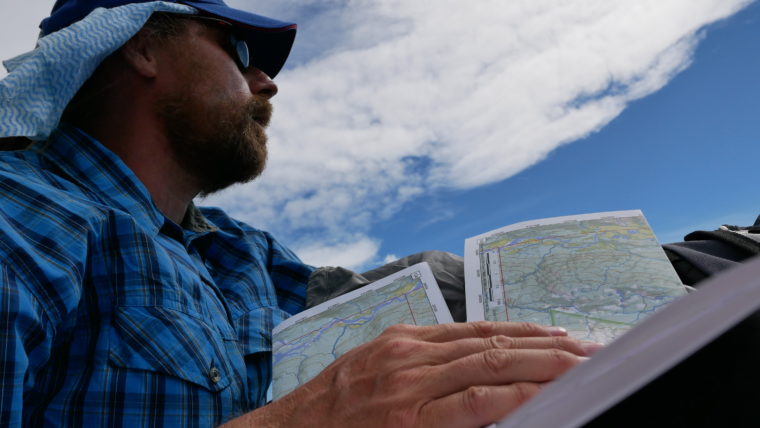

Tahltan cultural guide Curtis Rattray examines a topographical map in Mount Edziza Provincial Park.

Rattray flanked by the rainbow-hued Spectrum Range mountains.

Two months earlier, Rattray had invited The Narwhal to join a backcountry hike of a wild chain of volcanic mountains. I had never heard of Mount Edziza or the fire-coloured Spectrum Range, but I enthusiastically volunteered to go — despite the fact I’m not particularly experienced in the backcountry.

Rattray, a trail guide and cultural educator from the Tahltan First Nation, extended the offer to our team, saying simply, if you want to write about what’s happening in our territory, you should come up and learn about the land for yourselves.

It was an offer we couldn’t refuse.

The night before the trip, I found myself up at one o’clock in the morning anxiously checking and rechecking my pack job against the gear list Rattray had provided. I crammed the last of my spare batteries into an empty pocket and surveyed my lot: one bloated Arcteryx backpack stuffed to the brim with gear and food and a second smaller backpack cradling my camera, tripod and two lenses.

With a sense of relief that all my zippers could close I crawled into bed for a four-hour sleep before departing for an early morning flight.

Two days later it would be my oversight that would threaten to derail the entire adventure.

The first leg of our journey from Terrace is the drive up Highway 37, recently coupled with the expansive Northwest Transmission Line, a $736-million project built under the BC Liberals to spur development in the north. The long stretch of road branches off here and there to the many mining projects that have sprung up in the region in recent years.

Controversy over the mines has created division within the Tahltan Nation, Rattray says, with some welcoming the investment while others fear risks to the environment.

After the collapse of the tailings dam at Imperial Metals’ Mount Polley mine near Williams Lake in 2014, members of the Tahltan formed a blockade at the road up to the new Red Chris mine, owned and operated by the same company.

The tailings impoundment at the Red Chris mine holds seven times the volume as the waste pit at Mount Polley.

“There are a lot of different camps within the Tahltan,” Rattray said. “There are the environmental Christians, the pro-development people, the drinkers. I guess I don’t really belong to any of those groups.”

B.C.’s northern corridor, highway 37, is the main entrance route for the province’s northwest mines.

Rattray surveys Mount Edziza Provincial Park from the air. The park falls within the bounds of the Tahltan First Nations traditional territory.

Two of my travel companions, Bob and Sharon.

That’s not to say he hasn’t made his way through some of them, though. After a stint in the Canadian military and seasonal work doing trail maintenance, Rattray took to a lifestyle of heavy drinking.

“Sometimes after a night of drinking, I would wake up in the morning and just start drinking again,” he said as we travelled northward in the heat of the day, our packs flapping behind in the box of his pickup.

After a frank conversation with his boss at Kal Tire at the time, Rattray realized he’d rather drink than work and that was a problem. He was 29 when he quit drinking cold turkey. By 32 he was president of the Central Council and by his late 30s he had completed a double-major in political science and environmental studies at the University of Victoria.

Like any social collective, the Tahltan are a mix of complexities, Rattray explains, adding that — like most Indigenous communities across Canada — he sees the effects of intergenerational trauma and negative stereotypes wending their way through families and into the lives of Tahltan youth. And it’s those youth that Rattray thinks about most these days.

As an educator working within the Dease Lake school system, Rattray brings youth out onto the land as a part of his cultural revitalization work.

“The real reason I bring kids out is because I want them to experience a connection to the land for themselves. And I want them to see there are other ways to earn a living other than working for industry. There are so many resources going into training for mines and exploration. But what about guiding and tourism?”

Our pilot, Brian, fuels a small Cessna before our flight into the park.

Little Ball Lake, fed by nearby glaciers in the Spectrum Range.

We all gathered around a small scale the next afternoon, each waiting in turn to weigh our packs before loading onto a small Cessna floatplane on Tatogga Lake. When it was my turn I gracelessly lugged my bag onto the low platform. My fellow hikers let out a hushed gasp when they saw the tally — 49.7 pounds. I looked around with an anxious grin and let out a nervous laugh.

“I packed some heavy food,” I offered by way of explanation. I then moved my pack to weigh my smaller camera bag. Twenty pounds, bringing me to just shy of 70.

“Oh myyyyyyy gooooooood,” Sharon, the one other woman on the trip, sang out in a rasp. All in, her gear came to 35 pounds, half my total.

“I can totally manage the weight,” I announced. The others nodded in agreement, their eyes wide.

“What kinda boots you got there?” Sharon’s husband Bob asked, pointing towards the pair now dangling from the front of my pack.

“Oh, these are some old ones I got from my Mom,” I said. “They’re nice and broken in.”

The vibrant western slope of Mount Kunugu.

A sprawling glacier north of the Spectrum Range in Mount Edziza Provincial Park.

We were flown into Little Ball Lake in two successive trips to accommodate all of our weight. The 30-minute flight into the south end of Mount Edziza Provincial Park gave us a view of the wild terrain that would be our home for the next six days. The highlands are starkly cut off from the world that lies beyond these mountain ranges.

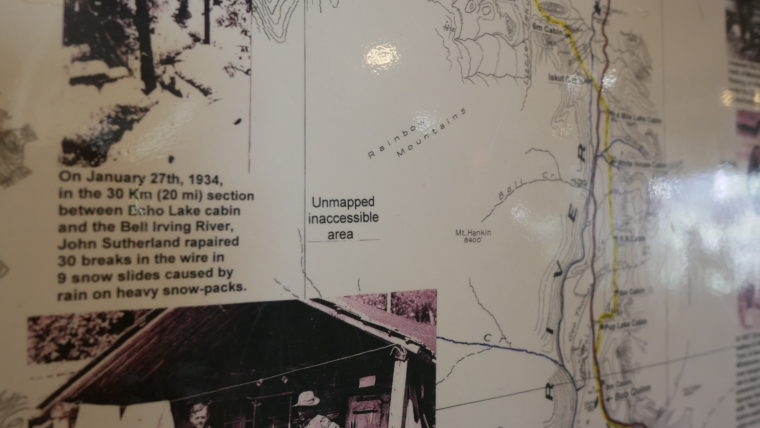

A 1929 map tacked to the wall of the Tatogga Lake Lodge shows the area we are heading into as a broad, blank space named Rainbow Mountains with the simple description, “unmapped inaccessible area.” Although largely unexplored by colonials, the region is well known to the Tahltan who travelled the territory’s volcanic cones, lava fields and rivers along historic trails that are in some cases still used to this day.

Historic map showing the Spectrum Range as an “unmapped inaccessible area.”

One evening Rattray delivered a short unconventional history of colonization accompanied by a vibrant hand-drawn map.

Early morning on Little Ball Lake.

The brilliant colours of the Spectrum Range, also called Rainbow Mountains, are the result of high mineralization within the volcanic region.

Mount Edziza Provincial Park is accessible only by foot, floatplane or helicopter.

The floatplane glides gently to the shore. We tiptoe along a slender pontoon and hop onto dry land, dropping our gear on the rocks.

When our pilot pushes off from the beach at Little Ball Lake we watch him depart. As he makes his way overhead we see the plane rock from side to side. We wave goodbye in return and when he’s out of sight we begin to survey for a flat spot to make camp. We planned day hikes from base camp for the first two days, before beginning the 18-kilometre journey to Arctic Lake. While Little Ball Lake was large enough to land on with a heavy plane, it is too small to accommodate a heavy take off. So, the only way out is Arctic Lake.

Little Ball Lake is crowded on its north shore by Mount Kunugu, a grand slope of orange and red spilling down from tall spires of black basalt. Volcanic landscapes are strangely animated, even thousands of years after they have stilled and cooled. Impossibly large rocks, flung far from an ancient volcano stick out here and there on the landscape with creaturely proportions.

“People call them gargoyles,” Rattray said. In such a wide expanse, the human eye constantly searches for movement, for moose or goat or grizzly, and the rocks seem to take on animal dimensions in my peripheral vision.

“I call them ancestors,” he said.

There’s a particular hollow sound we notice when passing over humps in the valley. “Listen!” Rattray will say to our group excitedly one day as he stomps his feet. “That’s what this place is named for in the Tahltan language, that sound that’s made when you walk over these old lava fields.”

In our search for a suitable site to pitch our tents I come alongside a patch of low-lying willow, disturbing a ptarmigan hen and her chick. She rushes out from the shrub, clutching an outturned wing to her side.

“She’s pretending to be hurt, eh,” Rattray said. “Protecting her chick. Let’s make camp somewhere else.”

We moved up the embankment and find a patch of tall grass. Rattray lies down in the grass to feel for any incline. It’ll do.

“In a line, not a circle,” Rattray instructs. “In case a bear comes to camp, you don’t want it running from one tent, straight into the next.”

Abundant quartz crystals and wildflowers such as hawkweed adorn the rocky landscape.

That evening as Mount Kunugu’s shadow enfolds the valley, Rattray pulls out a hand-drawn map of Tahltan country. The traditional lands of the nation, which are unceded to this day, cover 43,728 square kilometres of B.C., more than 10 per cent of the province’s land mass.

“If Tahltan territory was a country, we’d be the 109th largest in the world,” Rattray says, adding the region lies along the famed Ring of Fire, home to 123 of B.C.’s volcanoes.

“This area has two unique geological features: rugged peaks and plateaus. There are so many different habitats here for moose and caribou. The broad, wide valleys make for good winter habitat,” he said, “while the plateaus provide good range in the summer.”

Arctic cotton tufts along the Spectrum Range.

A ptarmigan hen eyes our hiking party.

Mount Kunugu’s basalt crown on display.

Detail of the Spectrum Range shows the signature coloured stripes of this particular volcanic zone. The Mount Edziza volcanic complex is made up of four central volcanoes.

As a member of the Tahltan Crow clan, Rattray said tradition dictates he must be buried by a member of the Wolf clan. “Wolf marries Crow, Crow marries Wolf. Wolf buries Crow, Crow buries Wolf,” he said.

“I told some of the kids that when I die, I want them to bring me out on the land and bury me. I told them they might get arrested, you know, because of permits and all that.”

As a self-described sovereigntist (Rattray half-joked at one point about making t-shirts that read “Indigenous Sovereignty All The Way”), Rattray is at odds with rules for the land, imposed by the province or enforced by the Crown.

“I could technically get in trouble from B.C. Parks for guiding you, eh?” he said to me that first evening.

“What do you mean?”

“I guess I should have disclosed that,” he grinned. “I don’t have a permit. Guides are supposed to get a park use permit and I don’t got one.” Rattray, no stranger to the folks at B.C. Parks, said he’s been pressed by government employees on this particular detail.

“They e-mail me once in a while, letting me know they know I’m guiding. They’ll say, ‘oh, hi Curtis, we saw your website. Um, great site by the way. Really. So about those permits…’ ”

He laughs to himself. “They can legally challenge me anytime. I expect them to. And I’ll fight them.”

Rattray already has plans in mind for how he’ll wage his legal battle — arguing for his sovereign right to use the land under the banner of the Tahltan Nation — but knows lawyers would likely force him to change course and argue instead that guiding is a constitutionally protected aboriginal right.

He knows that’s how Indigenous rights are fought for these days — argued and articulated under a legal and discursive framework established by colonial governments. It grates on him. We fall silent and look out to the hills.

Our first big day hike involves a 10-kilometre return trip climb up the mountain on the south side of Little Ball Lake. The gradual ascent provides us with a wider view of the Spectrum Range.

“Look,” I say, pointing to our tents below, “you can see our base camp.”

“Base camp?” Rattray retorts. “That’s our village.”

“What makes a village, Curtis?”

“Three or more tents,” he said matter-of-factly.

It was up on that southern mountainside where a slow-motion disaster began to unfold.

As our group took a break to rest through the height of the mid-day heat, I wandered away to photograph a nearby glacier. On my hike I stumbled slightly, kicking a small boulder. I knew what had happened even before I had looked down to see the toe of my right boot peeled back from the sole.

“Oh….shit…” I said out loud to no one but myself.

By the time our group reached the top of our climb, it was clear I was in trouble.

Approaching the icepack I turned to Bob and Sharon. “I’ve, uh, got a little situation with my boot.”

They looked down in disbelief at the now gaping rupture. It had already doubled in size, creating a flapping effect that worsened the split with each step.

“We need to start heading back right away,” Sharon said, looking at me.

The offending boots.

Dwarf fireweed feeds off the melt of a nearby snowbank.

A view south from the Spectrum Range.

We had a five-kilometre descent ahead of us and while my footwear was posing one sort of problem, another had simultaneously emerged. David, the fifth member of our hiking party was exhibiting early signs of heat exhaustion. Overdressed for the heat (in an attempt to escape an unholy presence of bugs, particularly mosquitos and horseflies), David had begun experiencing nausea and throughout the day had elected to eat very little.

Rattray inspected David’s clothing. “I thought you were wearing light, quick-dry stuff, Dave.”

“You’re overheating,” he said as we worked our way downhill.

Rattray on the Arctic Lake Plateau.

Rattray stopping at a water source.

“It’s a really special thing to be able to drink unfiltered water straight from the glaciers,” Rattray said.

I eventually insisted to David that I carry his pack for him. He relents and I sling his day bag over my chest. The trek to our tents takes over two hours and I try to hike as gently as possible, displacing my weight far back on my right heel. But the tug of the boot’s heavy sole does the slow work of detachment, a combination of heat, dust and old-boot brittleness working against my cautious steps.

At some point Rattray announces he will hike ahead to retrieve my camp shoes, a pair of lightweight water shoes, with soft foam soles. They’re no match for the sharp, hot rock we’ve been hiking, I think to myself.

I turn diagonal to side step my way down a steep embankment. We are less than a kilometre out from our tents. As I plant on some loose gravel I feel myself slide a little. I look down to see my socked foot blown completely through the boot. I hop down to level ground, the boot flopping from where it’s still securely tied around my ankle.

David and I are at the back of the group. I’ve been listening to him quietly curse to himself and glanced back a few times to see him struggle with uneven steps. Although we tied a handkerchief packed with snow to the back of his neck, he’s been unable to cool. He’s complaining of unquenchable thirst.

I stop to remove the exploded boot from my foot and David watches on. “Okay now you have to give me your pack,” he says. I hand off my pack to David and pass David’s pack to Sharon.

With boot in hand, I hike the last few hundred metres to camp. Mercifully, as we approach the lake the terrain switches from rock to dry moss. It’s pillowy soft.

When we reach the shore of the lake David begins to violently retch. Heat exhaustion hits him hard.

Rattray returns with my camp shoes in hand and surveys the scene. Standing in my one sock I instruct David to drop to his knees.

“That way if you fall over while puking you won’t hit your head,” I say and look at Rattray for approval. Given the sorry state he finds us in, he’s calm and measured — a state I come to recognize as his baseline.

As he positions himself to shade David’s face, I look his way and make an attempt at levity. “I guess you got a little bit of a handful between the two of us, huh?”

We both laugh.

“We’ll be alright,” he says. “Carol, can you go to camp and erect a shade tent for David?”

Rattray telling Tahltan transformation stories around the campfire.

Rattray on the open alpine tundra.

David is quick to rally that evening. As he rests, Rattray and I elected for a sunset swim. Stripping to our skivvies and using the cold water to escape the heat and the bugs, I ask Rattray about his experience growing up off reserve.

The son of a Scotsman and a Tahltan mother, he spent most of his early years in Taylor and Fort St. John, located in a heavily industrialized region of B.C. that consistently ranks high for crime among Canadian cities.

“I didn’t know it was such a violent place until I left and I was like, ‘oh, so hearing gunshots once a month isn’t normal?’ ”

Rattray describes himself as sounding but not looking Indigenous and so escaped a lot of the racial prejudice he saw other aboriginal kids face.

“I was called a half-breed,” he says. “But I always responded, ‘actually when you work it out, I’m more of a three-eights breed,’ ” he laughs.

But like a lot of Indigenous youth Rattray experienced a deep incongruity between what he learned in school and the stories he was told from within the Tahltan community.

“I always did have a hard time with school, because there was what I was learning there about Canada and then there were the stories my granny told me about what Canada actually is.”

“I felt this disconnect.”

Evenings were warm and bright until the sun dipped behind the ridgeline around 10:00pm.

Wild forget me not flowers.

Rocks are beautifully adorned with crystals all throughout the Spectrum Range terrain.

Now, working as an educator within the Dease Lake school system, Rattray says he and other Tahltan are developing what they call “restorative education” for their students, approximately 25 per cent of whom have been identified as high risk.

High rates of alcoholism, sexual abuse and social dysfunction plague the Tahltan Nation, “even if people don’t want to admit it,” Rattray says. And negative stereotypes and racist attitudes toward Indigenous peoples further entrench destructive self-regard, he added. I ask if he connects this suite of social challenges to the history of the residential school system.

“Not just residential schools,” he said. “I connect it to the whole history of colonization.”

“If you read analyses about the social impacts of stereotypes, you see their effect are real. And this is for everyone. When you’re bombarded with images of super athletes, the super model, Mary and Joseph or the noble savage — people just feel bad about themselves.”

On a narrow path heading back to our camp, I ask Rattray if he sees himself as a positive influence in the lives of the youth he brings out on the land. I hear his steps pause. I stop walking too and look back.

“I just want them to connect with their own Indigenous identity,” he said, neck craned back and looking at the sky. “That’s it.”

The glaciers of the Spectrum Range feed into the headwaters of the Iskut River.

Rattray and Sharon inspect my many, many blisters after a wet and sandy river crossing.

A braided river complex over an ancient Spectrum Range lava field.

The next morning we rummage for what boot-fixing supplies we have in our packs. One small roll of gorilla tape, a few feet of duct tape and some copper snare wire.

I wrap the toe of the boot as best I can and, once I’ve got my foot inside, loop tape around the centre from under the base up over the laces. The heel flaps open as I walk but it’s a Frankenstein job that’ll work. Each of our party takes a look in turn and agrees. I have about two feet of duct tape left, which I pack with me for a top-up on our day hike.

Our group plans to hike up and behind Mount Kunugu and Rattray brings his satellite phone to make a hail Mary women’s-size-7-boot call out to his aunt. Maybe, if she can get her hands on a pair of boots in Iskut, someone could drive them to the Tatogga floatplane terminal and if the company is dropping off any more hikers in Little Ball Lake…

There were a lot of ‘ifs’ in this plan. Up north, where cell service is spotty and people are generally less ‘plugged in,’ you’re lucky if you can even reach someone mid-day let alone coordinate a multiple-party boot swap.

Up on a high ridgeline, Rattray has a strong signal on the phone and gets his aunt on the line. He explains our predicament. He ends the call with a lack of optimism.

“We need to see if there’s even a floatplane coming this way in the next few days,” he says, his head shaking.

He places a second call to the air service. No dice. There won’t be another drop off at Little Ball Lake for four more days at which time we’d need to be halfway to Arctic Lake for pick up.

As Rattray listens on the line his head lifts up, “yeah,” he said, “that could work.” A pilot would make an emergency stop at Little Ball Lake to deliver more tape. It wasn’t new boots but it was, in short, salvation. Rattray rings his aunt again to call off the boot hunt.

We continued our climb of Mount Kunugu, our spirits buoyed by the news.

As we crest a small, low saddle between two peaks a wide expanse of high plateaus opens up on our right. To our left, the glaciers of Kunugu. The ground is strewn with porous lava rocks yet higher up the sides of the mountain are endless beds of angular dusty rock seemingly pouring from above in flows of coloured stripes.

Small, cool rivers flow direct from the glaciers above and we stop to fill our water bottles. The landscape feels like it’s watching us, shifting and whispering.

It pulses. You can almost see it.

The sweeping backside of Mount Kunugu.

The edge of Mount Kunugu’s impressive glacier.

Cracked rocks show the work of cold winter temperatures that fracture the rocks.

A small willowherb gone to seed.

Split and splintered boulders are strewn around us, evidence of the long work of expansion and contraction over geologic timescales. As we move along a steep mountain slope toward the highest glacier, we see chair-sized rocks weighed in place like heavy puzzles, cracked straight through along multiple lines but not yet disjointed.

The aliveness of the terrain is something Rattray avidly attends to. Often our talks on the trail are interrupted by a low roar, to which Curtis raises a silent finger and widened eyes. “Listen,” he says. “Rockslide.”

We intermittently hear these all around us. When we do, the group sometimes casts its anxious gaze to the towering rocks perched above our camp.

It’s not until this day that Rattray and I catch sight of one. Hiking about half a kilometre behind our party, up a steep embankment of sharp orange stone we hear the familiar rumble. To our right I spot the source of the noise. “There,” I point and Rattray and I watch as a stream of glacial melt undermines and drags a slope downwards. The muddy mix of stone and water thunders a short distance below in a slow, grinding slop — the sound of its soupy clatter echoing off the walls in the valley below.

I hurry up the pile of rocks we’re climbing, wondering what the forces of water are doing to unsettle the path I’m currently taking to the ridgeline above.

That evening, Rattray and I make our way to the lake for our evening swim. There on the rocks sits the holiest collection of objects I’ve ever laid eyes on: a full roll of duct tape, more tape, more wire and the most sacred item of all: a glistening red tube of Shoe Goo.

In my rapture I send a prayer of thanks to this unknown pilot who emerged from the skies to save me — life and limb.

A tiny tower of saving grace.

Rattray walks to our watering hole on the last morning of our excursion. Smoke from B.C.’s wildfires, which continue to burn in Tahltan territory, cast a haze over our final hike out.

“I don’t go for all that stuff about human nature being brutal,” Rattray reflects one day. “Out here on the trail you come to see what humans are naturally — cooperative, collaborative.”

“But humans…humans are consumers,” he later reflects on one of our last evenings. He pivots and turns to me, we’re standing high on a ridgeline near a mountain pass we’ll cross the next morning on our journey to Arctic Lake.

“You know the Matrix?”

“Yeah?” I feel my head tilt lightly to one side.

“I really like that movie. Especially that scene when Neo meets Morpheus for the first time, eh?”

Rattray describes one evening where he paused the video between each line so he could transcribe the dialogue.

“Morpheus says to Neo, ‘some people just know something is wrong. It’s like a splinter in their brain.’ ”

Rattray and I both look out to the valley as he continues. “I really like that line. I think a lot of people, you know, progressive people, they know something’s not right with the way things are. I believe they are connected with this innate, inherent hunter-gatherer spirit. The Tahltan believe in reincarnation. People, beings, they don’t die, they just start another journey. So these people are at a subconscious level feeling their hunter-gatherer roots. And they know something is wrong with how things are set up in our society.”

I ask how he connects that belief to his work as a guide.

“I guess I never really thought through that. But I just want people to come out here and experience the land. To see its value beyond just its use or aesthetics. Humans consume other things for their own well-being. That’s just a fact. Everything requires consumption whether it’s our pots and pans, our kitchen stove or the gas that fuels it. But there’s a right way to extract from the land.”

“These landscapes have spirits and we can’t consume in a way that angers these spirits. I want people to come out on the land, to get out here and see that.”

In my own mind I return to Rattray’s initial invitation and the reason I’ve been invited out on this adventure in the first place — to see this land for myself. I wonder: will this change my reporting? In a way I know it will. Or at least, I make a promise to myself I will allow it to. But I have this deep, abiding feeling that both Rattray’s mind and the landscape itself are places to which I’ll have to return, knowing the terrain is shifting. Evolving. Living.

What that means for the daily grind of an environmental journalist is difficult to capture. But I find myself drawn to the challenge Rattray has endeavoured to meet: to carry multiple, seemingly contradictory worldviews along with him as he journeys through the world. It’s much easier to lighten one’s intellectual load by trekking a more singular line of thought, not detouring from the path. It’s simpler, for example, from a reporting perspective to conceive of local First Nations as stalwart environmental protectors, fighting the Big Bad Mining Company come to threaten their land. But reality is almost always more nuanced than short, quick reporting will allow. It’s more subtle, more concealed and far richer than un-inquisitive minds often suggest. Even as I look at Rattray, he contains a world of complexities, of stories for which there is no simple telling. For him, the story of mining in Tahltan territory isn’t about a streamlined for or against. The question for Rattray falls into the much softer, much more difficult ground of ‘is there a way to do better?’

A relic of mine exploration just outside the southern border of Mount Edziza Provincial Park.

Our group’s final stretch to Arctic Lake.

Clay. The kind pilot who delivered the holy Shoe Goo.

On our final day we hike through what feels like endless kilometres of ancient glacial fields, riddled with large boulders. It makes for tough terrain. When Arctic Lake is finally in sight it signals we’ve reached the southern boundary of the park.

Rattray reaches for his binoculars and we take turns peering down to the water. Bob notices old barrels strewn about the beach.

“Are those rusted-out barrels down there, Curtis?” he asks.

“Yup. Old supply drops from mining exploration,” he explains. “They don’t always return to clean up.”

It’s the first evidence of human presence on the land we’ve seen in six days. Rattray said he’s considered creating a remediation program for the youth, so they can come out with a helicopter and clean up places like these.

With a thunder storm approaching at our backs the wind starts to pick up and we all joke about being stuck there forever. Over our laughter we hear the faint sound of a plane engine.

The pilot lands and angles his floats towards the shore. We start loading up the first of the gear.

The pilot stops in his steps at one point and looks at our group, scratching his head.

“Um…I just want to know, how are those boots doing?”

Editor’s note: Since the author traveled to Mount Edziza Provincial Park, terrible wildfires have plagued the region. Today parts of the park remain closed and the Tahltan First Nation is reeling from the impacts of wildfire in their community. Please consider donating to the Tahltan Central Government’s wildfire recovery fund.