Rocky Mountain coal mine in Alberta takes next step to expansion

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

I hear the wind before it hits me, a dull roar slamming the north face of Mount Cameron. The wind wraps around the ridge, hissing between the slabs of lichen-covered rocks, and biting through my hiking clothes.

Even though it’s only the middle of August, I feel the impending winter in the wind, and see it in the yellow-leaved poplar trees far below in the valley.

The full force of the gust greets me as I crest the ridgeline and step onto the peak of Mount Cameron. I dig in my pack for an energy bar and extra layers of clothes then hunker down a rock. Then I pull out my phone and open up Facebook.

Checking the internet out here feels bizarre.

It’s one more reminder that the Yukon, the place I grew up, is changing. I associate mountaintop cell coverage with Banff and Whistler, not the wilds of the Yukon, 400 kilometres north of Whitehorse.

I feel like I’m straddling two Yukons.

Cell reception in the last place you’d expect it: in the rugged mountains of north-central Yukon. Photo: Malkolm Boothroyd

South and west of me are cell towers, highways and airstrips. Roads and mines carve up boreal forest valleys and tundra plateaus. To the north and my east, the land is still remote and free of roads. Before me stretches the Beaver River Watershed, and beyond it the Peel Watershed.

These two Yukons aren’t static — one grows while the other shrinks. The Beaver Watershed teeters on the edge, one of many parts of the Yukon that could be transformed by a new wave of development.

Vancouver-based ATAC Resources Ltd. wants to cut a 65-kilometre resource road through the valley below me. The company holds claims to a series of gold and copper deposits east and west of the Beaver River.

Road access would slash the cost of exploration at these properties and make mining development more economical. The ATAC road could also bring serious ecological impacts to the watershed.

Roads are a driving force behind habitat fragmentation, the spread of invasive species and the disruption of water flows. Numerous animals avoid areas near roads, or change their migration patterns in response to roads.

Weathered wooden posts mark a mineral claim near Rambler Creek. The Yukon’s free entry mining system is a relic of the Klondike Gold Rush, and in much of the Yukon people can still claim mineral rights by pounding a post into the ground. Photo: Malkolm Boothroyd

Roads bring both costs and benefits. Many people who call the Yukon home first arrived here on a road trip up the Alaska Highway, and roads help people access beloved lakes, rivers and mountain ranges. At the same time many Yukoners value the remoteness of places like the Peel Watershed, far removed from the rumble of truck engines.

There’s one key difference between the ATAC road and other highways in the Yukon — resource roads service mining companies, not communities.

I pull my camera from my pack and snap a few images of the valley. Citizens of the Na-cho Nyak Dun First Nation have close ties to the Beaver River Watershed, however the area is unknown to many in the wider territory.

Collecting photos and stories from this area is a priority for the Yukon chapter of the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society, the environmental non-profit where I work. My friend Maury and I are here to capture photos of these mountains.

In 2017 the Yukon Environmental and Socio-economic Assessment Board (YESAB) ruled in favour of the ATAC road, but the board’s review left many questions unanswered.

ATAC’s belt of mineral claims extends more than 100 kilometres beyond the end of the proposed road. The company could be tempted to extend the road in the future, while other mining companies will likely look to build offshoot roads. In comments submitted to the board, the Yukon government acknowledged that “opening up a new all-season access route into the Beaver River watershed results in a high likelihood that additional industrial development will follow.”

Roads scar a hillside near Dawson City, Yukon. Photo: Malkolm Boothroyd

The board did not consider the avalanche of development the ATAC road could trigger. Its mandate is to evaluate the specifics of each project as it arises, but this provides few safeguards against incremental environmental impacts.

The Yukon government and Na-cho Nyak Dun First Nation are working on a land use plan for the Beaver River Watershed, though the plan is proceeding on the assumption that the ATAC road will be built.

The Beaver Watershed saga is part of a larger road-building dilemma that is playing out across the Yukon. The Yukon has a relatively small road network, but that’s changing.

In 2017 the federal government, territorial government and the mining industry pledged nearly $470 million to the Yukon Resource Gateway Project — aiming to improve access to mineral hotspots in the Yukon by building or upgrading 650 kilometres of roads.

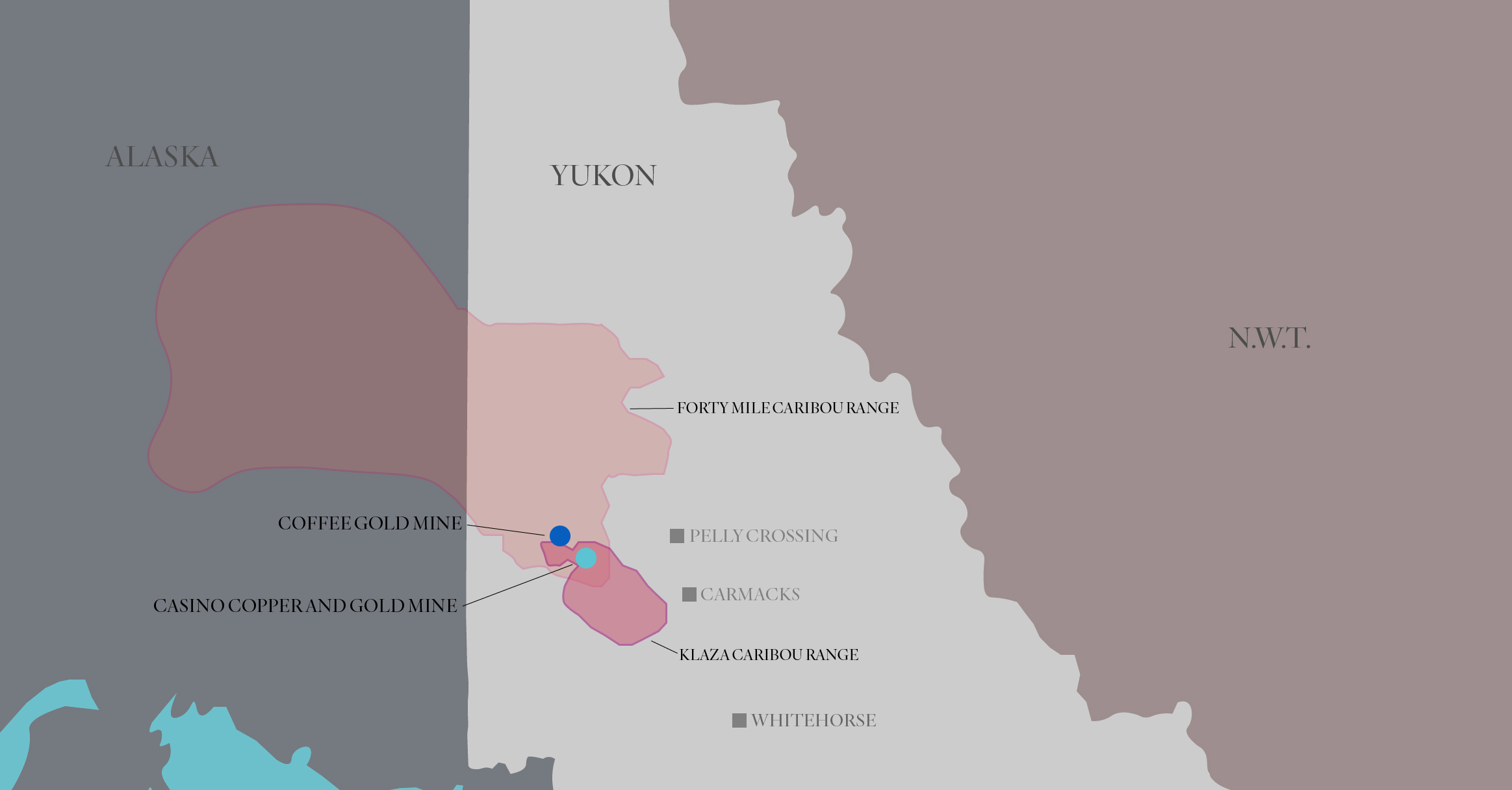

Map: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

The Yukon Resource Gateway Project would fund construction in the Dawson Range of west-central Yukon, and the Nahanni Range along the territory’s eastern boundary. The roads would service major mining proposals such as GoldCorp’s Coffee Mine and Western Copper & Gold’s Casino Mine. The latter plans to store tailings behind what would be the highest dam on earth — nearly as tall as the Eiffel Tower.

Beyond servicing these megaprojects, roads in remote areas like the Dawson Range could bring a flurry of new mineral exploration and extraction. In a letter of support for the Resource Gateway Project, the Yukon Chamber of Mines writes that the project would “lead to a significant increase in activity in this highly prospective district.”

Road construction and a corresponding spike in mining activity in the Dawson Range could have serious consequences for the Klaza herd: a type of morthern mountain caribou, listed as special concern under Canada’s Species at Risk Act.

According to Environment Yukon, the Klaza caribou herd faces “some of the most significant conservation concerns among all northern mountain caribou herds in Yukon,” owing in large part to roads and mining activity.

Klaza caribou spend summers in the alpine, and descend to lower elevations in winter. The herd has largely abandoned portions of its winter range where mining, roads and other human activities are concentrated.

Further road construction and development of the Casino Mine and others could force caribou out from high-value winter habitats in the northern part of their range. Increased road and mine development in the Dawson Range could also hinder the recovering Fortymile caribou herd from reestablishing its historical summer range.

Major road construction projects could usher in landscape-level changes to areas like the Dawson Range. The Yukon’s environmental review process is poorly equipped to address the cumulative impacts and domino effects that such projects could bring.

Wind ruffles the neck feathers of a young spruce grouse near Rambler Hill, above McQuesten Lake. Photo: Malkolm Boothroyd

According to the Yukon’s application for federal infrastructure funding (submitted under the previous government), the Resource Gateway Project would undergo environmental review as individual road components, not the program as a whole.

The application also notes that road components could be assessed by district offices — the lowest level of review permitted under the territory’s environmental assessment act. District office reviews take an average of 63 business days to conclude, while the impacts brought on by road developments could last for generations. The ATAC road was reviewed by a district office.

One by one, projects are being approved that are transforming the Yukon. This approach to environmental assessments makes it difficult to take a broad view of this development path — and ponder which version of the Yukon we want to live in.

Decisions with long-term implications for the territory should be made through the Yukon’s land use planning process. Land use planning was established under the Umbrella Final Agreement between the Crown and Yukon First Nations, and is designed to make collaborative decisions about future land uses, conservation and developments.

Projects like the Resource Gateway are unlikely to be evaluated as part of the territory’s land use planning process, due to how slowly planning has unfolded.

In the 26 years since the Umbrella Final Agreement was signed, only two land use plans have been finalized.

In contrast, the clock is ticking on the Resource Gateway Project: federal funding expires in 2022.

Water tumbles through an iron-stained creek, one of the countless tributaries of the Beaver River. Photo: Malkolm Boothroyd

Developments like the Resource Gateway could amount to de-facto land use planning: irreversibly changing the Yukon while circumventing the land use planning process.

More projects like the Resource Gateway and the ATAC road are sure to come.

Many Yukon government reports over the decades have envisioned new transportation corridors to stimulate mining development and link the Yukon to markets across the world. Meanwhile, the mining industry continually pushes for more infrastructure dollars. Well-reasoned, collaborative decision making — ideally through land use planning, is critical to arriving at the right resolutions over road developments.

A bull moose wades through a small lake in the subalpine meadow. The nearby creek is one of the 73 water bodies the ATAC Road would cross. Photo: Malkolm Boothroyd

The ridge where I’m standing is far out of earshot from the nearest truck, but the wind is loud enough. The gale continues relentlessly through the night. It’s still blowing the next morning, as my friend Maury and I hike through high alpine meadows. We trace the path of an iron-stained creek, one of the 73 creeks or rivers that the ATAC road would cross.

The willows thicken as we descend, and the sporadic spruce trees begin to form a forest. Maury finds a moose trail and we follow it through the trees, awkwardly clambering over fallen logs that a moose would trot over. There are fresh hoof-prints where the ground is soft.

There’s something special about navigating a landscape on trails worn only by the footsteps of grizzly bears and moose.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. A $335 million funding commitment to fund...

Continue reading

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

A trade war could help remake B.C.’s food system, but will family farmers be left...

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...