Rocky Mountain coal mine in Alberta takes next step to expansion

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

Wayne White parks his pick-up at the end of a bumpy logging road and steps out where Pyrrhotite Creek squeezes through a tiny slot in the bedrock.

It’s an innocuous looking trickle, but for decades this creek carried toxic effluent from the abandoned Mount Washington copper mine, virtually killing the Tsolum River.

“Four years of mining and a 40-year reclamation effort,” White, president of the Tsolum River Restoration Society, says as he gazes out over the Comox Valley on the central east coast of Vancouver Island.

He points to where the Tsolum River winds to its confluence with the Puntledge River, a few kilometres from Comox Harbour.

In 1967, after a year of construction and less than three money-losing years of operation, the Japanese backers of this ill-fated open-pit mine went bankrupt, leaving behind mounds of copper ore and waste rock blasted from the north side of Mount Washington.

Perched 1,300 metres above sea level, the mine was plagued from the start by a deep snowpack that lingered well into summer and made work difficult.

The miners walked away, but the environmental impact didn’t.

Wayne White, President of the Tsolum River Restoration Society walks along the edge of the copper mine on Mount Washington. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

The site of the Mount Washington mine on Vancouver Island. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

Today, it lives on as a textbook example of the complex and long-term challenge of mitigating acid rock drainage.

When mine waste and tailings are exposed to air and water, oxidation occurs. If mineral conditions are right, this process can produce acidic runoff capable of damaging downstream aquatic environments for decades — even centuries — if left unchecked.

Even before the last ore truck rumbled down the mountain, exposed mine waste was already leaching metal into Pyrrhotite Creek that would eventually decimate fish populations in the Tsolum River.

A v-shaped water gauge on Pyrrhotite Creek headwaters, just below the site of the Mount Washington mine. The majority of water testing done on Pyrrotite Creek is conducted here. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

A shot of a rock cut on the Mount Washington mine access road showing the signature white streaks where copper sulphides, or salts, have precipitated from rock containing copper ore. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

The cost to the local economy was pegged at between $2 and $3 million per year in lost fishing opportunities alone.

It took a multi-decade, multi-stakeholder effort to clean up this mine and nurse the Tsolum River back to health.

But when it comes to metal mines, the remediation work is never really over.

White understands this all too well. Before retiring several years ago, he was a career civil servant who worked in the environment ministry’s pollution control branch.

“We’ve learned as a community group that we constantly need to keep our foot on the gas to make sure government does what it says it’s going to do,” he tells me.

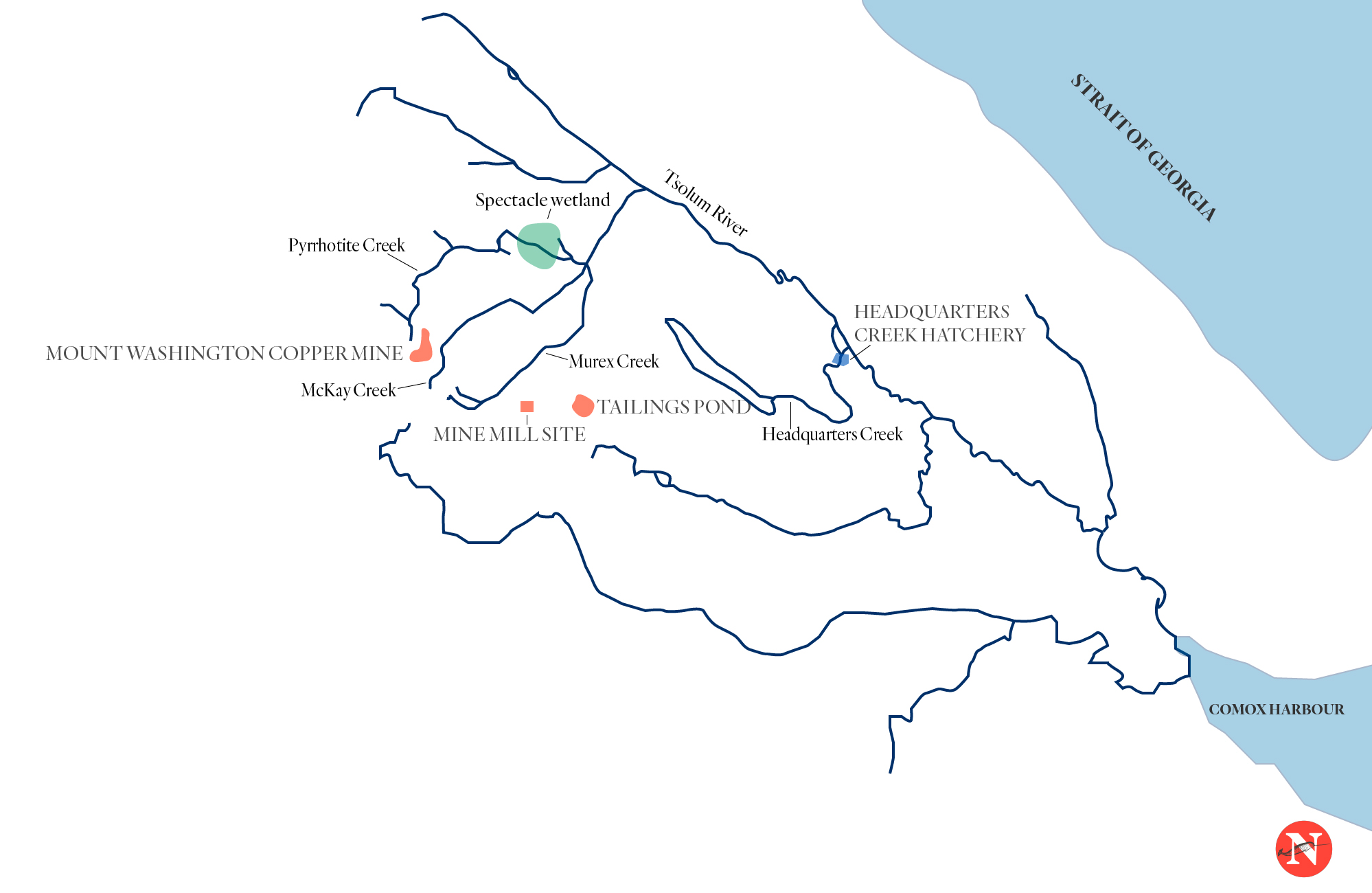

A map of the Mount Washington copper mine in proximity to three creeks that feed the Tsolum River. Map: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

Father Charles Brandt, another local concerned with the river, took a rather unconventional route to river conservation.

He was raised on a farm in Kansas, served in the U.S. Airforce and briefly studied ornithology at Cornell University, before turning to theology. In 1948, he was ordained into the Anglican church, before converting to Catholicism. He joined a Benedictine monastery in Oklahoma and eventually, this winding path led him to Vancouver Island.

In 1965, he moved to “The Hermitage,” a pastoral property next to the Tsolum River, north of Courtenay, where he lived until 1970.

Father Charles Brandt, longtime environmental advocate involved in the restoration of Tsolum River. Brandt is photographed in his book binding studio where a poster of the Mount Washington mine hangs on his wall. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

In the 1980s Brandt helped raise awareness about the collapse of salmon populations in the Tsolum River. “We started writing letters to everybody we could think of in government telling them that the Tsolum River was dead,” he told The Narwhal. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

Brandt, 97-years-old, helped found the Tsolum River Restoration Society. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

Brandt moved there as part of a plan to commune spiritually with nature, but his early days at The Hermitage also introduced him to fly fishing — and, eventually, a lifelong commitment to the Tsolum itself.

He would prove to be as dedicated to river conservation as he is to his faith. Brandt played a crucial role in the establishment of the Tsolum River Restoration Society, a leading force in the river’s rehabilitation.

“The first winter I was at The Hermitage I was walking across the Farnham Road bridge and looked down and saw a fisherman holding a beautiful 22-pound steelhead,” Brandt, now 97, says, sitting in the living room of his home on the Oyster River.

The Mount Washington mine is located on private land, thanks to a legacy that dates back to 1884, when a coal baron named Robert Dunsmuir was granted land on Vancouver Island — a giveaway that would eventually total 8,100 square kilometres, and included surface and subsurface rights.

In the ensuing years, these rights were parcelled up and sold to various interests, creating a muddy jurisdictional tangle that made it difficult for any one company to be held responsible for cleanup of the mine.

A view from the Mount Washington copper mine. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

The mine site’s ownership remains divided between companies and the provincial government. Better Resources Ltd. owns the precious metal, forest company Timberwest owns the trees and surface rights, and the Crown owns the subsurface rights.

Had the site been on Crown land, the abandoned mine would have fallen under the Ministry of Environment’s contaminated sites regulation — but being on private land it slipped through the cracks and landed in a sort of jurisdictional purgatory.

Making things more complicated, the mine’s closure also predated the introduction of reclamation regulations under the Mines Act in 1969. These regulations, now called the Health, Safety and Reclamation Code, hold companies accountable to “protect and reclaim land and watercourses affected by mining.” The act also requires mining companies to post financial security to pay for clean-up (although amounts required under B.C. laws are regularly criticized for being woefully inadequate).

In the case of the Mount Washington mine, the absence of a clear path forward meant the job of sounding the alarm fell to volunteers like White and Brandt.

Brandt became hooked on steelhead fishing at a time when metal leaching from Mount Washington had yet to trickle its way down through the watershed.

Back in the 1940s, the Tsolum was an angler’s paradise, with large numbers of pink, coho, chum and steelhead salmon.

But even then, the watershed was far from pristine.

The Tsolum River. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

Industrial logging — during a time when the importance of riparian setbacks to river health was poorly understood — caused erosion that damaged the natural shape and flow of the river and the pools, riffles and gravel spawning beds that are so important to fish. So did the removal of tonnes of gravel from the riverbed used to construct the runways at the Canadian Forces Base in Comox in the early 1940s.

Despite these challenges, the river managed to support healthy runs of salmon — until the acid runoff took its toll.

The spectre of acidic runoff remained more or less hidden until 1982, when the Department of Fisheries and Oceans released 2.5 million fry from a test hatchery on Headquarters Creek into the Tsolum. Two years later, a mere 10 pinks were counted in the river.

Pink returns tend to fluctuate greatly, but this decline was seen as catastrophic and mobilized the local steelhead-fishing community.

“We started writing letters to everybody we could think of in government telling them that the Tsolum River was dead,” Brandt recalls.

That caught the interest of John Deniseger, a government biologist heading up the Ministry of Environment’s environmental impact assessment branch at the Nanaimo office. Though the presence of copper in the Tsolum River was already known to fisheries scientists, the link between metal leaching at the mine and copper spikes in the river was poorly understood.

“It took a couple of years of detective work in the early 1980s. We knew there were no fish in the river, we just needed to show why,” Deniseger, now retired, says over the phone from his home in Bowser.

“Salts” form on copper ore, making copper water soluble and thus dangerous to fish. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

The Mount Washington mine poses unique challenges for local rivers, in part because of its location high in the watershed where snow can be deep enough to bury a four-storey building.

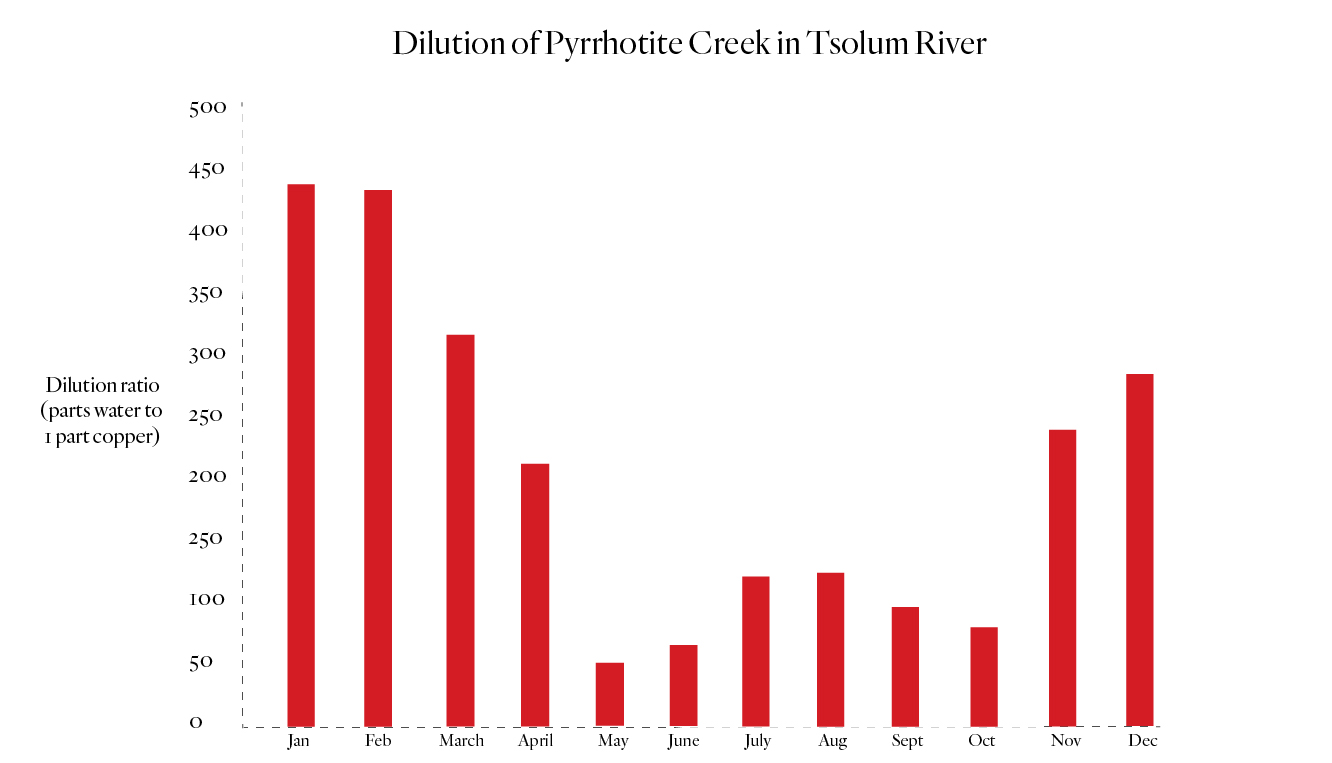

Runoff from Pyrrhotite Creek — fed by snow melting high above near the Mount Washington mine — peaks in May and June, sending a pulse of copper-laced water into the Tsolum in late spring and early summer at the precise time when the river’s water levels are lowest. If the flux of toxic run-off had come at times when water levels were already high, natural dilution could have been at least part of the solution, without anyone pointing a finger at the mine site.

The timing was poor for another reason; copper-laced water flowed into the Tsolum at a particularly sensitive time for fish populations, when fry are only just emerging from their gravel spawning beds and are at their most vulnerable.

A graph showing the annual dilution ratio of Pyrrhotite Creek within the Tsolum River. The flow of Pyrrhotite Creek is mainly driven by snowfall in the winter months, providing more water to dilute copper. January shows a dilution rate of 440:1, 440 parts water to one part copper. In May the dilution ratio plummets to about 50:1, 50 parts water to one part copper. Source: Tsolum River Partnership. Graph: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

Though the pinks leave the river earlier in the spring — thereby avoiding peak copper levels later in the season — the overall health of the river was degraded, Deniseger says, making it hostile to salmon, trout and the freshwater invertebrates on which young fish depend.

Deniseger’s sampling showed that, by the late 1980s, spring peaks of copper in the Tsolum ranged between 70 and 90 parts per billion — four to six times higher than the 15 parts per billion benchmark considered to be toxic to fish over the long term.

Further testing enabled Deniseger to zero in on the north pit of the mine as the primary source of acidic runoff.

Locals now knew they had a toxic river on their hands, yet it would take many more years of trial, error and community pressure on the government until anything was done to set it right.

The Mount Washington mine where water is not diverted around capped waste piles. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

The province undertook its first major reclamation effort between 1988 and 1992.

Though the price tag was $1.5 million, it was a rather low-tech endeavour: covering the mine waste with a cap of glacial till and building a channel to divert water around the contaminated area.

Expectations were high, and the province even announced an ambitious target to reduce levels of dissolved copper by 95 per cent.

Water testing from 1993 to 1996, however, revealed the effort was a dismal failure. Although there was evidence of some decrease in copper levels in the following years, no one could agree on the reason.

The Tsolum River task force, which included community members, government agencies, local First Nations and industry, lobbied in 1998 to have the Tsolum declared one of B.C.’s most endangered rivers.

The Tsolum River. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

White holds up copper-bearing rocks at the mine site. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

The remnants of the abandoned copper mill at the Mount Washington mine. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

By 2003, a new solution was floated: diverting Pyrrhotite Creek in the Spectacle Lake wetland, located below the old mine mill site.

The goal was to use the natural wetland to filter out metals before the water was returned to Pyrrhotite Creek and eventually into the Tsolum River.

It worked, in part. Copper was reduced by another 40 per cent, falling well short of the target deemed acceptable for the Tsolum.

Deniseger says the partial success was an important milestone because it began to shift public perception of the Tsolum.

“We needed to change the perception that the river couldn’t be fixed,” Deniseger says. “After the wetland diversion it was like someone had flipped a switch. There was an instant positive impact on water quality.”

Yet Deniseger says he and others knew the passive form of treatment would likely be temporary at best; the small wetland’s peak effectiveness was expected to last between 10 and 15 years then gradually diminish over time.

Hiem along the banks of the Tsolum River. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

The positive results from the wetland approach also led to new interest from industry, catching the eye, in particular, of the Mining Association of B.C.

“Mount Washington was giving the mining industry a black eye,” White says. “They had an interest in being part of a good news story.”

Along with the provincial ministry of mines, the Mining Association of B.C. joined the multi-stakeholder Tsolum River Partnership and the search for a more permanent fix began.

The partnership settled on a novel technique that had been used in other industrial clean-up applications, but rarely for mine closures. It involved capping the offending mine waste with a thick bed of glacial till, then laying down a bituminous membrane — basically a half-centimetre-thick layer of bitumen sandwiched between robust geotextile fabric — over which another metre or so of glacial till would be laid.

Armed with a plan vetted and approved by mining reclamation experts, Deniseger and the partnership asked the Treasury Board for $4.5 million to carry out the project.

“Considering annual economic losses of of $2.7 million from the Tsolum, it was a good return on investment,” Deniseger says.

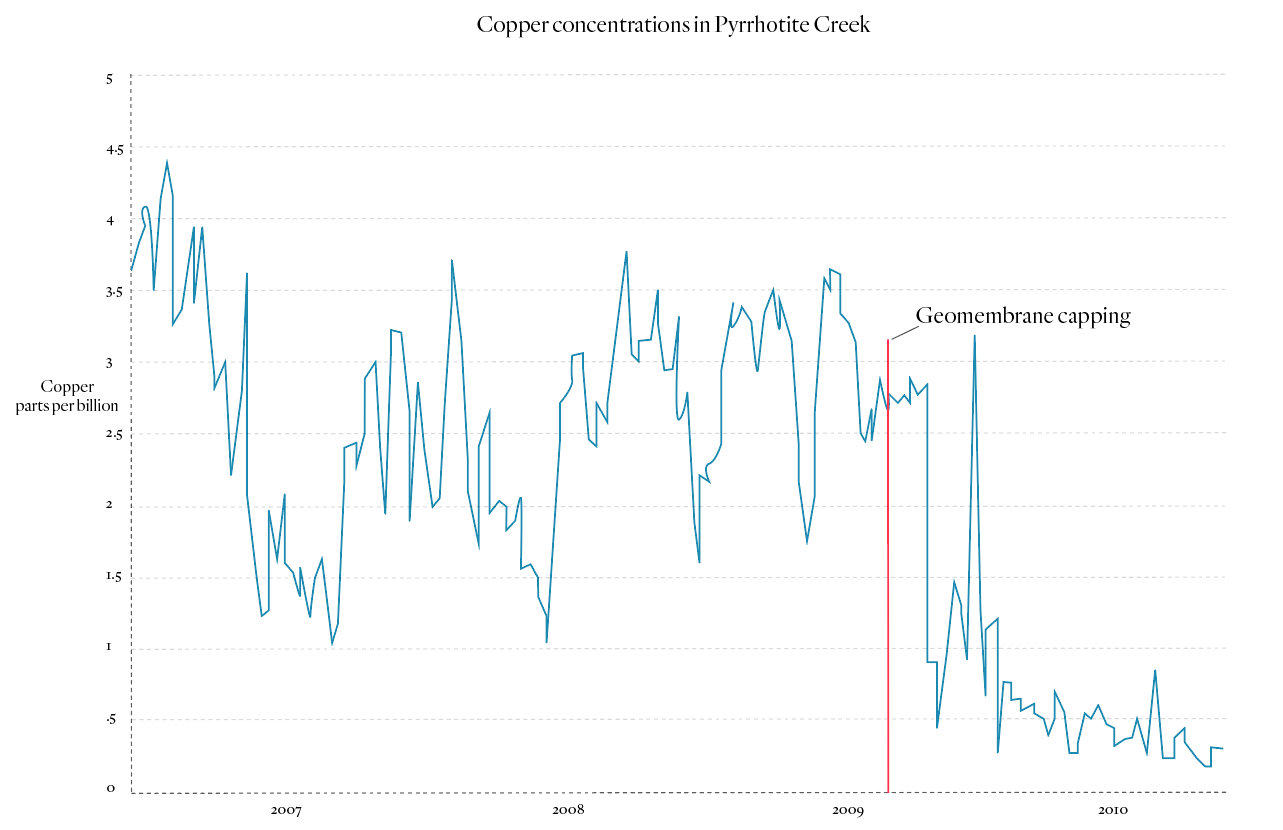

They got the funding, and in 2009, contractors got to work. Over the next six months, dump trucks carried more than 128,000 tonnes of gravel up the steep mine access road, while workers rolled out 12 kilometres of the membrane, heat sealing the joints by hand.

Afterwards, much of the site was covered with logging debris and replanted with alder as an erosion control measure.

In 2009 waste rock at the Mount Washington mine was covered with geomembrane and buried under 128,000 tonnes of gravel. Drainage ditches built into the cap divert clean water away from the capped waste. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

Pryyhotite Creek flowing into the natural Pyrrhotite Creek wetland. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

A small amount of water from an under pipe that drains the area beneath the 12 kilometres of geomembrane. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

Fish responded quickly.

In 2013, a little more than three years after the north pit was capped, roughly 61,800 pink salmon returned to spawn in the Tsolum, the largest return since the 1950s. In 2015, 129,000 pinks came back to the river — a record return since fish counts began in 1953.

For Brandt, it was like witnessing the rebirth of a beloved river.

“It felt really good to see fish back in the river, that all that volunteer effort had paid off,” Brandt says.

Wayne White calls it a “good news story,” one that has not gone unnoticed.

The Tsolum River Partnership received the 2011 Premier’s Award and the 2011 B.C. Mine Reclamation Award.

Copper concentrations in Pyrrhotite Creek, 2007-2009. Source: Tsolum River Partners. Graph: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

For his part, Deniseger was personally honoured in 2013 with the Premier’s Award for many contributions throughout his career, not the least of which was helping to forge the unique partnership necessary to help solve the Mount Washington problem.

So far the Ministry of Energy, Mines and Petroleum Resources appears confident about the integrity of the Mount Washington mine remediation. In an emailed statement, a ministry spokesperson wrote that inspections in 2018 and 2019 “reviewed and determined that the observed erosion of the till is not compromising the cover,” noting that a rip discovered in the cover was promptly repaired.

White holds a piece of the bituminous membrane used to cover and seal mine waste on Mount Washington. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

White at Pyrrhotite Creek just downstream of the Mount Washington mine. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

“The contractor monitoring the site is reviewing the feasibility of establishing a vegetation cover,” the statement said.

The costs of failure are devastatingly expensive, and impacts can last for centuries. In the western United States, historic mining has damaged an estimated 25 per cent of all watersheds.

In Canada, taxpayers are on the hook for astronomical mine remediation costs at the Giant mine near Yellowknife and Yukon’s Faro mine, both of which surpass an estimated $1 billion, while the Britannia Mine on Howe Sound is expected to cost taxpayers $100 million.

The Tulsequah Chief mine, built in the 1950s along the B.C.-Alaska border, has leaked acid mine drainage into a tributary of the Taku, the prevailing salmon-producing river for southeast Alaska. Despite pressure from Alaska, the province has been unable to successfully clean up the mine for more than 60 years.

On a sunny morning, biologist Caroline Heim, the Tsolum River Restoration Society project coordinator, walks a stretch of the lower Tsolum River in hip waders, looking for pink salmon that dart through the riffles in schools of 20 and 30.

More than 20 volunteers have turned out for the annual fish count. The water is so clear that Heim can easily spot redds, the shallow depressions of clean gravel scoured by female salmon into which they deposit eggs.

“The main issues facing the Tsolum today are low water flows in the summer and restoring riparian areas,” Heim says, adding that sedimentation from past logging continues to have downstream impacts on fish habitat.

Industrial logging along the Tsolum River occurred before the importance of riparian zones were widely understood. Logging, in addition to the removal of tons of gravel from the rivers bed, disturbed the natural spawning grounds of salmon in the Tsolum. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

The banks of the Tsolum River have been restored after years of intensive logging. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

Hiem helped replant the banks of the Tsolum River with willow as part of the Tsolum River Restoration Society’s work. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

In many ways, today’s Tsolum is a picture of a healthy river.

But the story of the river’s health is still evolving.

For White, Mount Washington is like a rocky relationship that you can’t get out of, no matter how hard you try.

Since the 2009 pit capping, runoff has begun to erode channels in a steep section of the covered mine site — the only part of the site not revegetated or covered with woody debris. The fear is that the membrane will be uncovered and exposed to damaging UV radiation.

“It’s something we’re concerned about,” White admits.

White says the restoration of the Tsolum River is a “good news story” but says the mine site still requires regular monitoring and maintenance. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

Twelve kilometres of bituminous membrane were rolled out to seal mining waste at the Mount Washington mine. White, pictured with the author far left, says that runoff has washed away sections of the gravel cover, leading him to worry the geomembrane underneath could become exposed to damaging UV radiation. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

The Tsolum River Restoration Society plans to continue to put pressure on the government to make sure the mine is properly cleaned up.

Public pressure may be the most important piece of any mine reclamation effort, according to William Price, an environmental scientist with Natural Resource Canada’s mine effluent section.

Speaking at an October seminar in Smithers, hosted by the Bulkley Valley Research Centre, Price noted that a robust regime of maintenance and monitoring is critical to prevent the unraveling of years of volunteer effort and expensive remediation.

According to Price, it’s not whether or not society will need the products of sulphide mining, which go into electric vehicle batteries, flat screen TVs, wiring homes and countless other every day utilitarian needs. Rather, it’s whether or not we’ll manage mines responsibly.

Update December 17, 2019 at 3:45 p.m. PST. Two photo captions were updated to clarify the role of water drainage on the mine site. The first concerns the under pipe which drains water captured under the geomembrane. The second caption clarifies the image of Pyrrhotite Creek draining into the natural wetland. The costs of clean up at the Faro and Britannia mines were clarified to reflect the fact these amounts are estimates and not costs already paid by taxpayers.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. A $335 million funding commitment to fund...

Continue reading

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

A trade war could help remake B.C.’s food system, but will family farmers be left...

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...