B.C. has a new policy for staking mining claims. Why doesn’t anyone like it?

B.C. previously allowed mineral claims without First Nations consultation. It was court-ordered to fulfill its...

On the corner of Lilac Street and Mulvey Avenue, three tall, stately American elm trees bear an ominous orange dot. It’s Winnipeg’s mark of death: the familiar, tell-tale sign that a tree won’t live through the coming winter. It marks the tree as one of thousands of victims of Dutch elm disease, a fungal wilt spread by elm bark beetles that’s plagued the city’s trees since 1975. For many Winnipeggers, it’s a sign of mourning.

“The elms have gone down fast on this street,” says Julie Price, who lives on Mulvey between Lilac and Wentworth Streets. Five or six years ago, Price says, mature elms lined these boulevards, their leafy archways cradling the street below.

“And then I started watching giant after giant coming down. It feels like a funeral every time that happens.”

The city’s beloved canopy — one of its best defences against the impacts of a warming climate — is thinning, and the numbers are grim.

Between 2018 and 2021, the city cut down more than 46,500 trees due to a range of factors, including Dutch elm disease — a removal rate of more than 11,600 trees per year. In the same time, the city has only managed to plant about 23,500 trees, averaging 5,900 annually. Data from the city’s 2021 report on the state of the urban forest offered even more jarring statistics: just one public tree is planted for every three trees removed, and in 2020, the city replanted just 19 per cent of the trees it took down.

Overall, the city has lost hundreds of thousands of trees in recent years to invasive pests, like Dutch elm disease and emerald ash borer, development, storms and neglect. It’s leaving the city’s urban forest — its trees and greenspace — on life support.

“We have a crisis in our urban forests,” says Gerry Engel, president of Trees Winnipeg, a 30-year-old non-profit dedicated to protecting the city’s canopy.

“We’re losing mature trees — so many of them every year. It’s seriously concerning.”

Trees play a key role in protecting life and preserving a balance in both local and global ecosystems. A healthy urban forest helps clean the air and stabilize the planet’s climate by absorbing heat-trapping carbon dioxide and pumping more oxygen into the atmosphere, while the canopy’s shade provides valuable cooling for individuals and buildings.

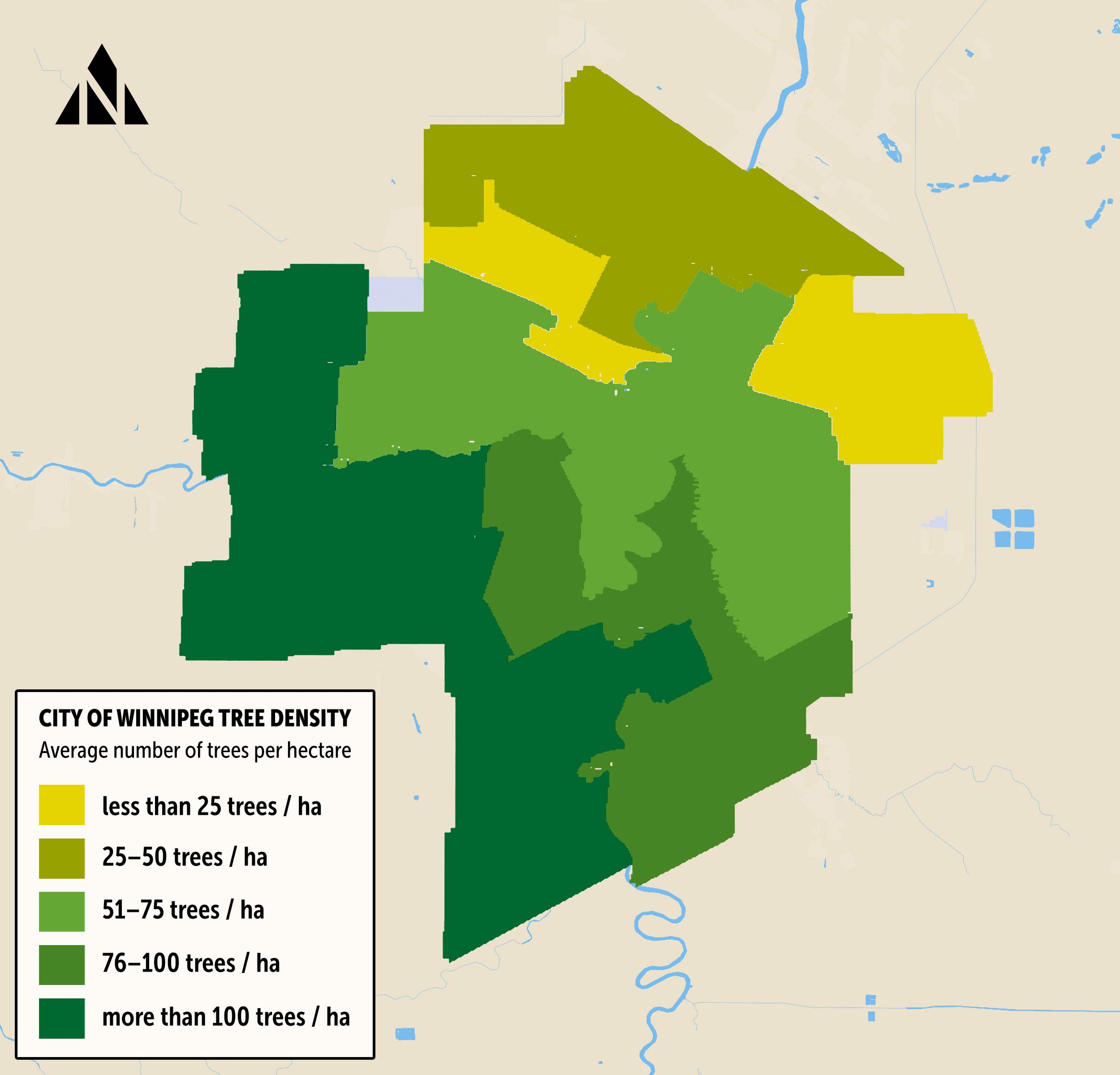

The impacts of Winnipeg’s tree losses are the most stark in the city’s low-income neighbourhoods in the north end and downtown core where the canopy cover is far more sparse than the rest of the city — just nine per cent of low-income neighbourhoods are covered by trees compared to the city wide average of 20 per cent, according to statistics released by the city in an urban forest strategy document — and residents are left to cope with hotter temperatures that could trigger heat-related illnesses.

Despite the longstanding crisis, Mayor Brian Bowman says, trees were hardly on mayoral candidates’ radars during the 2014 and 2018 election cycles. In fact, it wasn’t until after his second term kicked off that he put the urban forest on council’s agenda with the One Million Tree Challenge as a potential solution.

The plan is based on asking residents to step up and help plant the trees themselves by the time the city’s population reaches one million people in about 20 years.

“Part of the million-tree challenge is recognition that the municipal government can’t do it all,” Bowman says. “I think that’s clear for anybody who’s been paying attention that there’s more that needs to be done.”

In the middle of another election campaign, it is clear Bowman’s plan is falling flat, with just three per cent of the target planted to date. In the meantime, the city’s planting efforts on public land have fallen short, too, leaving Winnipeg with fewer trees today than there were when the challenge began.

In late 2020, residents on Price’s block of Mulvey got tired of waiting for the city to tend to the thinning boulevards. After years asking the city to grind out fallen elm stumps and replant the boulevard, Price and a handful of neighbours got together to plan a planting party of their own.

“A few people brought up the issue that it’s the city’s responsibility to do this, and I think we all agree with that, but we also agreed we wanted trees and had been pestering and weren’t getting anywhere,” she says.

“Most of us can afford to help out, so when you have the ability to support the city’s goal of a million trees and make our own little neighbourhood more beautiful, most of us want to do that.”

It took the group hundreds of dollars and hundreds of hours to choose trees (mostly maples, oaks and lindens), plan planting locations and purchase supplies. But over the past two years the group — who call themselves Mulvey Trees — have managed to plant more than a dozen saplings on their boulevard, while taking steps to protect the last of the decades-old elms.

“It was really nice vibes that first planting, pretty celebratory,” Price says.

Outside Sue Fonseca’s house, one of the remaining old elms stands tall and healthy, towering over the peak of her roof. She wraps her arms as far as she can to reach around the wide trunk, and points to her top floor window, from which she’s long watched and spoken to the tree. It’s hers, in a sense; she’s protective of it. So much so that she and other members of Mulvey Trees chose it as one of three to treat against Dutch elm disease.

Dutch elm disease alone claimed 30,000 public and private trees between 2016 and 2020 — enough to line 300 city blocks. As the disease takes hold, a section of the elm’s leaves turn yellow, then brown, and begin to curl in on themselves. The leaves die, but tend to stay hung on the tree, their limp and brittle carcasses signaling the tree’s untimely end. It only takes a few weeks for the disease to spread through branches, and once a tree is infected, the disease can quickly travel through the root system to other elms nearby.

Once a tree is sick, nothing can be done.

Treating a healthy elm against the disease can cost between $500 and $700 (depending on age and girth), and must be repeated every three years to give the tree a shot at survival. It’s an expensive endeavour, but one Mulvey Trees hopes to keep up in order to preserve their slice of the canopy. Those older trees provide the most value to the neighbourhood, as their large canopies offer more shade, carbon storage and oxygen production.

Resident Oly Backstrom is calling on local politicians to deliver a comprehensive solution to the city’s canopy woes.

“We’re trying to create our own micro-solution,” says Backstrom. “But what we’re doing isn’t a systemic solution; not every block can mobilize, not every block has a critical mass of people who can afford it, where there’s enough connective tissue.”

There are 300,000 boulevard and park trees (known as public trees) in the city’s urban forest inventory. Overall, Winnipeg is home to more than three million trees, most of which are on private land.

As is the case in many North American urban centres, Winnipeg’s urban forest is made up of monocultures. The city has the largest urban elm population in North America, with ash and elm together making up more than half of the public tree inventory, and more than a quarter of the canopy as a whole.

That over-representation is worrisome: both species face a major existential threat, leaving the city in a race against time to keep its canopy alive.

The threat of emerald ash borer, an invasive beetle capable of decimating a city’s entire ash tree population in under 10 years, has loomed over Winnipeg since the pest was first detected here in 2017. Even the city’s mature bur oaks, native to the riverbank forest, are suffering due to age, urbanization and the loss of healthy soil.

As trees start succumbing faster to disease, maintenance is also a challenge. Pruning, which helps remove dangerous dead wood and preserves tree health, has fallen woefully behind the industry best practice of every seven years — in Winnipeg they’re pruned every 31 years.

“There are huge challenges ahead of us as a city to protect and maintain what we have,” Engel says.

In May, the city’s forestry department released the first draft of its urban forest strategy, an attempt to face the challenges head-on. The No. 1 objective is to set and achieve a target for the city’s overall canopy, and make recommendations to council about how to achieve it.

At present, that canopy target is set at 24 per cent by 2065 — as in, 24 per cent of the city’s ground is shaded by trees — an increase of seven percentage points from the baseline set in 2018. That’s behind other jurisdictions — Toronto has set a 40 per cent target by 2050, Vancouver set a 30 per cent target for the same year and Guelph, Ont., which has a similar population density to Winnipeg, set a 40 per cent target by 2031, according to a 2021 Canadian Institute for Climate Choices case study.

Still, for Winnipeg, it’s an ambitious goal, requiring an all-out effort: the city will have to start replacing every tree it removes, hold emerald ash borer and Dutch elm disease at bay, increase tree diversity and rally a mass planting effort among private citizens.

No budget dollars have been allocated to the urban forest strategy as of yet, however the report itself acknowledges it will need to overcome years of underfunding to bring the forest back to life.

Since 2016, Winnipeg’s urban forestry budget has hovered around $11 million, with the bulk of funding dedicated to pruning and Dutch elm disease control. The funds increased to $12 million in 2021, and could notch up another two per cent next year, depending on council’s 2023 budget.

The city also promised $25 million in capital funding between 2020 and 2024 for urban forest enhancement and reforestation. The city has also secured $7.3 million in new funding from the federal government’s 2 Billion Tree program, which council hopes to spend planting tens of thousands of new trees.

But the urban forest strategy is careful to point out that, despite increased funding, pruning, maintenance, removal and planting targets are still falling behind, thanks to “factors not yet accounted for” in the budget.

To make up the gaps, the city has decided to turn to its residents for help through the One Million Tree challenge, which faced funding shortfalls of its own. The city has offered Trees Winnipeg just a few hundred thousand dollars to run the challenge over the past three years, a far cry from the more than $40 million the project was projected to cost at its inception. The rest will need to be made up by donation or through sponsorships.

According to the city’s own projections, Winnipeggers would need to plant 50,000 trees per year for 20 years to succeed with the challenge. Early administrative reports to council noted it could take up to five years to generate that pace, but this year the city was forced to halve its planting target from 40,000 trees to 20,000, suggesting the challenge is running behind.

Asked whether his challenge has been a success so far, Bowman hesitates a moment before saying the program is “off to a strong start — in the middle of a global pandemic.”

“There was never, at least for me, an expectation that we’re going to plant a million trees right out of the gate. But rather, we’re just like a tree; we’re planting the seeds for a challenge to grow in the coming years.”

It’s a compelling analogy, but planted seeds still need maintenance, attention and resources to grow — and that’s been a holdup for the One Million Tree Challenge, too. While Engel says the challenge is still in its infancy, he acknowledges the program has faced staffing challenges, pandemic interruptions and the pressing need for more public buy-in — be it through planting or donations.

Along with dedicated budget lines, this year’s voters want to see stronger bylaws to protect the urban forest from development.

The Trees Please Coalition was borne out of the Glen Elm neighbourhood’s desire to protect its dying elms and has grown to encompass several community groups invested in protecting the canopy. The group focuses on lobbying all levels of government to rethink their approach to the urban forest.

“The sentiment was right, the desire was right, but the execution was way off,” Trees Please president Erna Buffie says, when asked about Bowman’s challenge. “If the city is going to do something like that, it has to put its money where its mouth is, and historically, this city has not invested in green space.”

Buffie believes the city’s best plan of action would be to view the urban forest as critical natural infrastructure and treat the trees like assets. The city’s draft urban forest strategy — a first-time effort to institute a long term plan for the canopy — suggests city staff are on board.

The strategy estimates the cost of replacing each tree with a similar one is upwards of $3.3 billion. Winnipeg’s three million trees store nearly $40 million worth of carbon and sequester another estimated 39,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide each year. The shade they offer can cut resident’s heating bills by 20 to 50 per cent, while shielding people and infrastructure from extreme heat, harsh winds and heavy snow. The trees keep an estimated one million cubic litres of water out of the city’s stormwater system each year, while helping stabilize riverbanks against floods, and raise property values by up to 15 per cent.

All together, the city estimates the urban forest provides more than $14 million worth of benefits every year. The stakes of losing the canopy are incredibly high.

By classifying the trees as infrastructure, Trees Please believes governments will be able to instill more long-term funding and planning for the urban forest, while helping protect Winnipeg from the worst impacts of climate change. Over the years since its inception, Buffie says the coalition has seen progress towards this goal through new financial investments, but the city has a lot of work to do to move beyond planting to long-term protection of the canopy.

“The big issue is that wherever these programs have been enacted in other jurisdictions, they’ve failed because they plant the trees, but they do nothing to maintain the trees,” Buffie says.

The coalition has asked mayoral and council candidates to make three commitments: replanting two public trees for every tree lost, bringing the pruning cycle back to the seven-year industry standard and incorporating better tree protection rules for construction projects. All of the mayoral and ward candidates the group has met with have signed onto the pledge.

Bowman, who is not seeking re-election, agrees the municipal government could do better in preserving what’s already there.

“We’re one of the last cities to have aggressive bylaws with respect to plantings and new developments,” Bowman acknowledges. “That’s something that’s been historically lacking.”

And that’s something Martha Barwinsky of the city’s forestry department hopes to impress upon the incoming council. In the public engagement process for the urban forest strategy, Barwinsky says one message came through loud and clear: “We need to have better tree protection in place.”

“There’s lots of challenges with tree protection and preservation associated with urbanization and development,” she says.

The city provides a few incentives for developers to preserve existing trees such as zoning bylaws that offer credit for each tree protected during infill development. But these aren’t hard and fast rules.

It would take specific bylaws — the likes of which have been implemented in cities such as Toronto, Vancouver, Brampton and Surrey — to keep private property trees safe from development, and it could take years to see such bylaws in Winnipeg.

“Our biggest challenge with implementing a private tree bylaw is that the City of Winnipeg Charter (Act) does not provide us with the authority to regulate trees on private property at this time,” Barwinsky explains.

This means a property owner can cut down a tree on their own land without consulting the city.

“That’s scary,” Barwinsky says. “I hear that all the time and it just makes me shudder. We do not have anything in place to prevent that from happening.”

There’s no question trees are key in the city’s fight against a warming climate; “trees provide us a liveable space,” Barwinsky says.

Then there are the intangibles, which motivate groups like Mulvey Trees to plant a boulevard canopy of their own.

Barwinsky says Winnipeggers have shown they have “a love affair” with their trees — and she’s noticed it peak in the past five years.

“Unfortunately, that interest and that recognition tends to come from a sense of loss,” Barwinsky says. “You see the canopy going, and people really tend to take notice.”

Updated on Oct. 5, 2022, at 11:15 a.m. CT: This story was updated to correct the statement that Jenny Motkaluk had not committed to the Trees Please pledge. As of Sept. 26, all mayoral and ward candidates Trees Please had met with had signed onto the pledge.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On March 17, federal Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre...

Continue reading

B.C. previously allowed mineral claims without First Nations consultation. It was court-ordered to fulfill its...

British Columbia has vowed to fast-track several mining projects in an effort to blunt the...

Alberta introduced North America’s first industrial carbon tax in 2007. Now an industry email obtained...