The site of an infamous B.C. mining disaster could get even bigger. This First Nation is going to court — and ‘won’t back down’

Xatśūll First Nation is challenging B.C.’s approval of Mount Polley mine’s tailings dam raising. Indigenous...

In a rebuke to Canada, the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD) has expressed regret that work continues on the Coastal GasLink pipeline, the Trans Mountain pipeline and the Site C dam without the free, prior and informed consent of Indigenous Peoples.

A letter from the committee to Leslie Norton, Canada’s permanent representative to the UN office in Geneva, says the federal government “has provided no information” on any measures it has taken to address concerns raised in the committee’s December 2019 decision statement — which included a request that work on all three projects be immediately suspended until consent is granted.

UBC professor Sheryl Lightfoot, a Canada Research Chair in Global Indigenous Rights and Politics, heard about the letter, dated Nov. 24, 2020, this week.

She said it behooves the federal government to pay attention to the committee — one of the world’s leading human rights bodies — as it repeatedly calls out Canada for defending its actions instead of taking steps to comply with international human rights law.

The committee is drawing attention to the fact that the lack of free, prior and informed consent from Indigenous Peoples in Canada is racial discrimination and needs to be corrected, Lightfoot told The Narwhal.

“CERD is trying to highlight that Canada will not be in compliance with the legally binding human rights treaty it signed until it develops a process that allows Indigenous Peoples to have equal rights of consent, like all other peoples,” said Lightfoot, a citizen of the Lake Superior Band of Ojibwe who is senior adviser to the UBC president on Indigenous affairs.

“I’m not sure that message is being received.”

In its two-page decision statement, the UN committee urged Canada to immediately cease the forced eviction of Wet’suwet’en Peoples who oppose the Coastal GasLink pipeline and Secwépemc Peoples opposed to the Trans Mountain pipeline, to prohibit the use of lethal weapons — notably by the RCMP — against Indigenous Peoples and to guarantee no force will be used against them. It also urged the federal government to withdraw the RCMP, along with associated security and policing services, from Indigenous lands.

The committee said in its December 2019 statement that it was alarmed by the escalating threat of violence against Indigenous Peoples in B.C. and disturbed by the “forced removal, disproportionate use of force, harassment and intimidation by law enforcement officials against Indigenous Peoples who peacefully oppose large-scale development projects” on their territories.

Weeks later, with a B.C. Supreme Court injunction in hand, heavily armed RCMP conducted a weeklong raid on Wet’suwet’en camps along the Coastal GasLink pipeline route, igniting a storm of protests across Canada.

Women sing and drum outside the Unist’ot’en Healing Centre near Houston, B.C., during last year’s RCMP raid on Wet’suwet’en camps. The UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination is criticizing Canada’s violent response to Indigenous Peoples’ peaceful protests. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Molly Wickham, spokesperson for the Gidimt’en checkpoint along the Coastal GasLink pipeline route, said Canada’s human rights transgressions extend beyond refusing to suspend work on the pipeline, as the committee originally requested.

“They’ve gone even further and have violated even more of our international rights as Indigenous Peoples,” she said in an interview by satellite phone from her home in Lhudis Bin on Wet’suwet’en territory, about 10 kilometres from the pipeline construction.

“After that [first UN committee] letter was written and sent to Canada, they went ahead and brought violence into our communities and removed Indigenous Peoples from their own territories. They removed Hereditary Chiefs and Matriarchs from their own territories, which is a violation of the UNDRIP and it’s a human rights violation.”

Grand Chief Stewart Phillip, president of the Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs, said the federal government needs a strong and stern reminder of its legal and constitutional obligations to Indigenous Peoples after failing to act on the UN committee’s recommendations.

He called the government’s response to the recommendations “a snapshot of the ongoing arrogant attitude of the prime minister in regard to these issues.”

“They haven’t done anything at all. And that’s been the pattern.”

The Grand Chief recalled the night Justin Trudeau was elected prime minister in October 2015.

“The acceptance speech was just an incredible multitude of promises to Indigenous Peoples that there would be a seismic change in our lives, in terms of ensuring that the Trudeau government would respect the principles reflected within the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples — and ensure that accordingly our interests would be reflected in resource development decisions and things of that nature,” he said.

“None of that ever happened.”

In its letter, the committee said it regrets that Canada interprets the free, prior and informed consent principle, and the duty to consult, “as a duty to engage in a meaningful and good faith dialogue with Indigenous Peoples and to guarantee a process, but not a particular result.”

Lightfoot said one of the strongest messages in the letter is that securing the free, prior and informed consent of Indigenous Peoples is not just about process, but also about the outcome.

“While Canada feels that they have an appropriate process, the CERD is highlighting that they cannot stop there — that they need to make sure the process is leading to an outcome that is consent.”

Consent is frequently confused with veto power, Lightfoot pointed out.

“There seems to be a fear somehow that if free, prior and informed consent is upheld that Indigenous Peoples will have more rights than everyone else. That is completely 180 degrees off,” she said.

“The situation right now — and what CERD is trying to point out, in multiple letters — is that Indigenous Peoples do not have equal rights to everyone else, and that is discriminatory,” she continued. “Canada is violating the human rights treaty that it signed. In the current situation, the party that actually has veto power right now is Canada.”

Last year, as word spread of the UN committee’s request that Canada halt the three resource projects, the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers issued a press release saying the decision statement “reflects an embarrassing ignorance of Canadian law.”

But Indigenous Rights scholars pointed out that the United Nations, with its overarching focus on human rights, was created in the wake of the Holocaust and other atrocities to ensure increased global scrutiny of human rights in individual countries, and that Canada championed the convention and was one of the first nations to sign on.

In November 2019, the B.C. government passed legislation to incorporate the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in B.C. law. The declaration states that large resource projects require the free, prior and informed consent of Indigenous Peoples on whose territories the projects will be built.

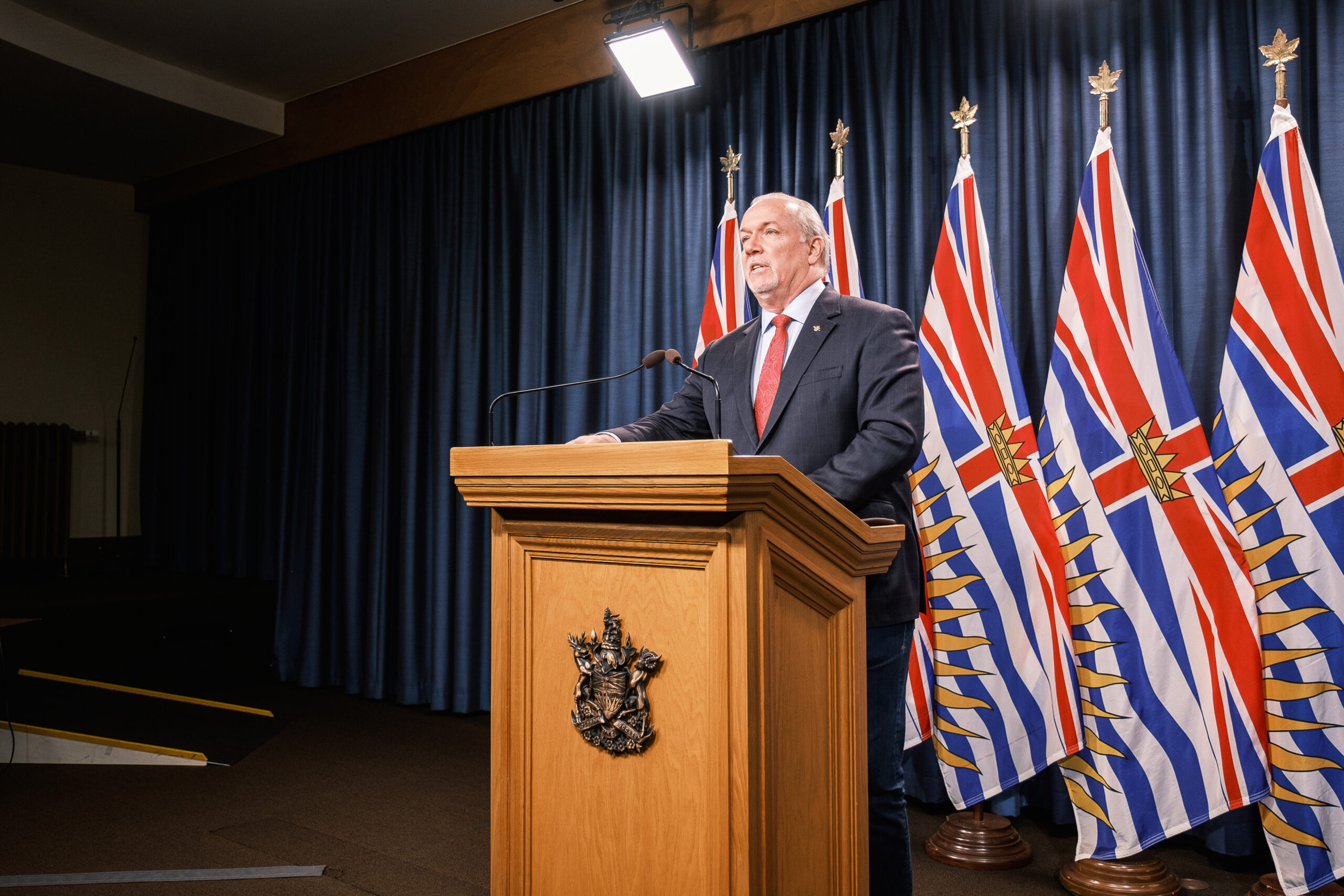

Since the B.C. government passed legislation to adopt the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, there have been questions surrounding when and how the process will be executed. Photo: Province of B.C. / Flickr

How the declaration is going to be implemented remains an open question and the Wet’suwet’en conflict of early 2020 illustrates the complexity of this commitment.

Lightfoot called the B.C. legislation the “beginning of a process” to collaboratively determine what implementing the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples will look like in B.C.

“Collaborating with a diversity of peoples across British Columbia takes time. And dialogue takes time. And reaching negotiated agreements takes time.”

She said the three resource projects that concern the UN committee should be included in the action plan required by the B.C. legislation to bring provincial laws into harmony with the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

The government promised to create that plan by the end of last year but has not yet delivered it. Lightfoot said progress has been slow.

“I know that we’ve all been interrupted by a global pandemic, but the pandemic doesn’t make these other issues go away and, in many respects, it exacerbates them. I would personally like to see the efforts on the provincial action plan be sped up in the coming years.”

In December, the federal government introduced Bill C-15, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act. If passed by Parliament, Bill C-15 would require the government of Canada, in consultation and cooperation with Indigenous peoples, to take all measures necessary to ensure Canadian laws are consistent with the rights of Indigenous peoples set out in the Declaration.

Grand Chief Phillip said there must be a process to compel the federal government to fully respect the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in its legislative agenda.

“There has to be immediate action. … When the third parties [proponents of large resource projects] rise up in outrage then we’re in the right spot. Because, right now, the government has catered to the corporate world at the expense of our international, constitutional and legal rights in regard to access to lands and resources and the ability to establish [an] economic base that will allow us to properly caretake our people.”

Lightfoot urged the federal government to take advantage of the UN’s Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples to obtain technical assistance and impartial advice on how to better implement UNDRIP, as the committee has recommended.

The mechanism includes an extensive database on how other countries have resolved particular Indigenous Rights issues and access to seven global experts in Indigenous Rights implementation.

“They can be of incredible assistance,” Lightfoot said, noting that countries such as New Zealand and Finland have sought advice and technical assistance through the expert mechanism.

“CERD is pointing to the fact that Canada may want to consider that as well and go get some advice from the UN itself, which has a global vision. I would recommend that.”

The B.C. government deemed all three resource projects in question essential services during the COVID-19 pandemic, kindling fears that out-of-town workers will bring sickness into First Nations communities.

In late December, following 250 cases at five industrial projects, including at the Coastal GasLink and the Site C work sites, Provincial Health Office Dr. Bonnie Henry issued a public health officer order requiring the projects to scale back their operations.

But critics said it was too little, too late, following reports that Wet’suwet’en people, including an Elder who was admitted to ICU in hospital, were infected directly from someone working on the Coastal GasLink project or LNG Canada project. Barely one week after the provincial order, companies were permitted to rapidly rebuild their workforces.

“Coastal GasLink is bringing COVID into our communities and we’re starting to see the loss of our Elders, and our language speakers and cultural knowledge holders,” Wickham said.

She said Wet’suwet’en communities are preparing a submission about the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic for the UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

“We’d like to see the UN take more action on the current COVID crisis that is happening.”

The controversial Site C dam is one of the projects mentioned by name in the letter from the UN committee. There have long been questions over whether the project infringes on Indigenous Treaty Rights. Photo: Jayce Hawkins / The Narwhal

Last February, the Federal Court of Appeal dismissed an application from First Nations — including the Coldwater Indian Band, Squamish Nation and Tsleil-Waututh Nation — seeking to overturn Ottawa’s approval of the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion, owned by the federal government, on the grounds Indigenous Peoples had not been adequately consulted.

In July, after the Supreme Court of Canada denied an application to challenge the decision, leaders of the three First Nations said they would be exploring other legal options, calling the decision “a setback for reconciliation.”

Construction on the troubled Site C dam is also forging ahead despite a long-standing civil action brought by West Moberly First Nations, a Treaty 8 member, alleging that the project and two previous dams on the Peace River constitute an unjustifiable infringement of Treaty Rights. A trial is scheduled to begin in March 2022 and will last about six months.

“It’s important that we all keep engaging and pushing and advocating for the realization of Indigenous Rights in this country.”

“We have a long way to go in terms of solving these problems,” Lightfoot said.

“It would not benefit anyone to step away from that process. It’s important that we all keep engaging and pushing and advocating for the realization of Indigenous Rights in this country.”

The committee has asked Canada to report back on the status of federal legislation to implement the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, including on the extent to which Indigenous Peoples are involved in drafting the legislation.

It has also requested information on the implementation of the B.C. legislation — especially in relation to the three resource projects in question — as well as information about further efforts undertaken to engage with Secwépemc and Wet’suwet’en communities affected by the Trans Mountain and Coastal GasLink pipelines.

The report is due Nov. 15.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. When I visited my reserve, Moose Factory,...

Continue reading

Xatśūll First Nation is challenging B.C.’s approval of Mount Polley mine’s tailings dam raising. Indigenous...

As the top candidates for Canada’s next prime minister promise swift, major expansions of mining...

Financial regulators hit pause this week on a years-long effort to force corporations to be...