In a Nova Scotia research lab, the last hope for an ancient fish species

Racing against time, dwindling habitat and warming waters, scientists are trying to give this little-known...

This is part two of a three-part series on Wood Buffalo National Park featuring photos by Louis Bockner, Sierra Club BC. Find the first story here and the third story here.

The old black bear, unconcernedly snuffling through the grass beside one of the unpaved roads that criss-cross Wood Buffalo National Park, poses for a classic vignette of Canada’s largest national park.

Further down the road, a lynx bounds across a ditch, then sits, watching from the cover of the trees, and, a few kilometres away, a herd of buffalo shuffle their calves into the bushes.

The four-legged examples of “outstanding, universal value” that helped put Wood Buffalo on the prestigious list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites in 1983 are on full display, but, with time running out for Canada to meet 17 UNESCO recommendations to improve the park’s environmental health, many fear Wood Buffalo is heading for the list of World Heritage Sites in Danger.

A bull bison on one of Wood Buffalo National Park’s main roads.

A bear, seemingly unperturbed by a cloud of mosquitoes, eats foliage in Wood Buffalo National Park.

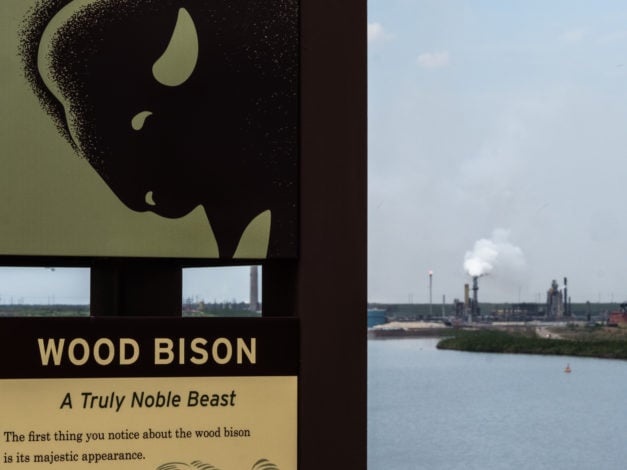

Syncrude operation pictured from the company’s wood bison recovery program lookout.

Syncrude operation in Alberta’s oilsands North of Fort McMurray.

Progress has been slow since UNESCO monitors visited the 44,807 square kilometre park at the invitation of the Mikisew Cree First Nation, resulting in a report last year that the park is under threat from unbridled oilsands development, dams on the Peace River and lack of cumulative impact studies on the Peace-Athabasca delta.

Map of threats to Wood Buffalo National Park from UNESCO report.

“The combination of climate change and massive hydrological alteration has resulted in ecological, socio-economic and cultural impacts. Simultaneously the delta is at significant risk from upstream industrial development along both the Peace and the Athabasca Rivers, most strikingly from the expanding Alberta oilsands,” says the report, adding that management of the park is inadequate given the potential for toxic spills and leakage or breaches of tailings ponds.

The World Heritage Committee wants an action plan to be submitted by December 1 this year. Parks Canada is working with 11 Indigenous groups within the park, other federal government departments and the Alberta and Northwest Territories governments to meet that deadline.

A progress report was submitted to the World Heritage Committee in February, but it is a cumbersome process and disagreements with First Nations are simmering.

Sunrise on Pine Lake in Wood Buffalo National Park.

Sunrise over Pine Lake in Wood Buffalo National Park.

“There’s a feeling that Parks is dictating to Indigenous groups, but Parks is saying they are fighting a timeline and we have to make it happen. It’s very paternalistic,” said Becky Kostka, Smith’s Landing First Nation lands and resources manager.

There are also growing concerns about whether it is possible to pull together an action plan before the deadline.

“This is June and it’s due in December. It’s not looking good,” said Mikisew Cree director Melody Lepine, who is planning to give an update to the World Heritage Committee meeting in Bahrain this week.

“Not a single thing has been done for the Peace-Athabasca Delta,” she said.

Mikisew Cree Chief Archie Waquan echoes concerns about the timing.

“Parks is being a little too slow on some of the issues. I think we will have to put light or something under them to get this through by December,” he said.

There is also the overarching — and unanswered — question of whether any government would be willing to rein in oilsands development or construction of the Site C dam to save the Peace-Athabasca Delta, one of the largest freshwater deltas in the world.

Becky Kostka, lands and resources manager for Smith’s Landing First Nation.

Fort Chipewyan residents have watched as channels in the delta have dried up over recent decades, with dams on the Peace River, withdrawals of water from the Athabasca River by the oil and gas industry and climate change identified as the major culprits, and few are confident that substantive action will be taken.

“Soon we will have no delta. It’s so dry it it will be a good place to build a golf course,” said taxi driver Bill Tuccaro.

No one is expecting a total clampdown on oilsands development, said Mikisew Cree elder Terry Marten, “but it’s a matter of making sure it’s done properly to protect our way of life,” she said.

A visit to the the headquarters of Wood Buffalo National Park in Fort Smith confirmed the complications, with staff unable to answer questions until other departments were consulted.

The progress report outlines steps to address the recommendations and sets out how governments will work together, said Audrey Champagne, Parks Canada media relations officer, in an emailed response to questions from The Narwhal.

“It also signals that engagement with Indigenous communities is critical to the development of the action plan,” she said.

Alberta’s oilsands north of Fort McMurray.

Proposed site of Teck’s Frontier Mine 30km south of Wood Buffalo National Park. If built it would be the largest mine ever constructed in Alberta’s oilsands.

Tailings ponds in Alberta’s oilsands.

Staff and funding have been committed to the Wood Buffalo action plan, Champagne said.

“Canada is confident that, through collaboration with provincial and territorial governments, key stakeholders and Indigenous groups, we can create a path forward to ensure the future of Wood Buffalo National Park,” she said.

A strategic environmental assessment, a stepping stone to the action plan, was released in May, confirming problems with water levels, climate change and pollution, but the assessment immediately drew criticism for compiling existing research rather than conducting new studies.

“I don’t think it’s a document that, ultimately, will be very impactful,” said Bruce Maclean of Maclean Environmental Monitoring, a company that has worked with Mikisew Cree for more than a decade.

However, there are bright spots on the horizon for Wood Buffalo with the whooping crane population increasing, making the flock the only self-sustaining population of whooping cranes in the world.

“In 1941, there were 21 whooping cranes in existence and the population estimate now is 431 birds in the Wood Buffalo flock, so that’s a great success,” said Rhona Kindopp, Parks Canada resource conservation manager for Wood Buffalo.

“This is the second highest number of nesting pairs since our stewardship began in the 1940s.”

Wood bison herds, which are protected in the park, are also doing well, with about 3,000 animals and, although about 40 per cent are infected with bovine tuberculosis or brucellosis, that is better ratio than in other populations, Kindopp said.

And, as the action plan slowly takes shape, there is agreement that the UNESCO scolding has resulted in much-needed attention to the remote park, with international eyes now focused on Wood Buffalo.

The Narwhal’s reporter Judith Lavoie travelled with Sierra Club BC campaigner Galen Armstrong and Sierra Club BC photographer Louis Bockner to Wood Buffalo National Park in early June. Lavoie’s travel expenses were paid by The Narwhal, with the exception of a flyover of a section of Wood Buffalo National Park, for which she snagged an empty seat in the plane.