B.C. has a new policy for staking mining claims. Why doesn’t anyone like it?

B.C. previously allowed mineral claims without First Nations consultation. It was court-ordered to fulfill its...

The water is like glass and the salmon are jumping on a Wednesday morning in September as I head out on a boat with the Heiltsuk Coastal Guardian Watchmen.

We’re on the water no longer than five minutes when we stop at a shallow and guardian Walter Campbell pulls out a fishing rod.

“My dad showed me this spot,” he said. “I grew up on the water.”

The mission is to catch 10 rock fish to use for bait in crab traps. It takes no longer than 15 minutes for Campbell to reel them in.

The bait will help attract invasive European green crabs into traps set by the guardians in an attempt to stem the tide of the voracious creatures.

The Narwhal’s editor-in-chief Emma Gilchrist watches Walter Campbell, a member of the Heiltsuk Coastal Guardian Watchmen, fish in Heiltsuk territory while filmmaker Jayce Hawkins of Approach Media looks on. Photo: Louise Whitehouse / The Narwhal

Six guardians are employed full-time in Heiltsuk territory, on B.C.’s central coast, and patrol the territory five days a week on three different boats. They track ship traffic and wildlife, keep an eye out for poachers and uphold Indigenous laws.

Before becoming a guardian, Campbell was a commercial clam digger in Gale Passage. But on Oct. 13, 2016, that changed. A watchperson on an American-owned tugboat, the Nathan E. Stewart, fell asleep and the boat ran aground at 1 a.m. at the mouth of Gale Creek in Seaforth Channel.

It took 17 hours for oil spill responders to arrive on site from Prince Rupert. In the meantime, 110,000 litres of diesel, lubricants and other pollutants were spilled into the water.

The Texas-based Kirby Offshore Marine Corp. — the owner of the tug — was eventually fined $3 million for the spill. A civil case for damages filed by the Heiltsuk Nation is ongoing.

Three years later, when I ask members of the Heiltsuk Nation about that day, I can’t help but notice the way their expressions change, like they’re recalling a painful nightmare.

“The whole water was just pink with diesel,” guardian Jordan Wilson remembers.

“We were helpless, defenseless, to stop it from spreading.”

Wilson takes notes as part of his duties as a member of the Heiltsuk Coastal Guardian Watchmen. Photo: Louise Whitehouse / The Narwhal

Jordan Wilson, one of six Heiltsuk Coastal Guardian Watchmen, says the water turned pink the day the Nathan E. Stewart sunk. Photo: Louise Whitehouse / The Narwhal

When oil spill responders finally did arrive, they tried to surround the spill with an oil containment boom, but winds and waves forced it open in parts, according to a Heiltsuk report on the 48 hours after the spill.

Kelly Brown, the director of the Heiltsuk Integrated Resource Management Department, was the first member of the Heiltsuk to be notified of the spill. The call came at 4:30 a.m., more than three hours after the tug had first hit the rocks.

“Ninety per cent of all our food and all the resources we depend on are in that area,” Brown said.

The Heiltsuk rallied to do what they could, as they waited hours for a team to arrive with supplies, only to have them deploy defective equipment in unfamiliar conditions.

In the midst of the catastrophe, the seed was planted to create a new way of dealing with oil spills on the north central coast.

“As our community’s economy, environment, and way of life hung in the balance, we promised ourselves this would never happen in our territory again,” said elected chief councilor Marilyn Slett about a year after the spill, on the day the Heiltsuk announced a plan to establish an Indigenous Marine Response Centre.

Heilstuk Tribal Council’s elected chief councillor Marilyn Slett says Heiltsuk have more people working in their territories than Parks Canada or the Department of Fisheries and Oceans. Photo: Louise Whitehouse / The Narwhal

The 196-page report, Creating a World-Leading Response Plan, describes the likelihood of marine incidents on the central north coast, evaluates best spill response practices around the world and says an Indigenous Marine Response Centre located on Denny Island — adjacent to the existing Canadian Coast Guard base — could respond to all incidents in the study area within five hours and to 80 per cent of incidents in three hours.

“We have a very well-established guardian watchmen program and we’re really proud of it and they are the eyes and ears on the water,” Slett said. “They’ve responded to distress calls, responded to the Nathan E. Stewart, responded to emergencies, so for us it was a natural step in terms of looking at marine response.”

The proposed Indigenous Marine Response Center would employ 37 full-time staff and crew. The annual operating cost is estimated to be $6.8 million, with an estimated $11.5 million needed for start-up costs.

“We have more people working in our traditional territories than Parks Canada, than DFO,” Slett said. “We have Heiltsuk here who are trained, who are out there monitoring.”

The view from a Coastal Guardian Watchmen vessel in Heiltsuk territory. Photo: Louise Whitehouse / The Narwhal

The Heiltsuk Coastal Guardian Watchmen pull ashore. Photo: Louise Whitehouse / The Narwhal

Brown said before the spill First Nations had not been fully engaged in oil spill response plans.

“We believe that as Haíɫzaqv (Heiltsuk) people with all the local knowledge for the area, that we’re the right place to put an Indigenous Marine Response Centre that would be managed by ourselves,” he said.

As the Heiltsuk await federal funding for the program to move ahead, part of the problem is the colonial mindset that kept the Heiltsuk out of the loop during the initial stages of the spill response in the first place.

“There’s still no recognition of the Heiltsuk government,” Brown said. “We have to be recognized as a government here. We’re the ones left having to manage whatever the disaster left.”

A spokesperson for Transport Canada told The Narwhal that collaboration with Indigenous peoples is vital to protecting Canada’s coasts and waterways and said “the government of Canada wants Indigenous peoples to play an active role in marine safety.”

“As part of Canada’s $1.5 billion Oceans Protection Plan, we are working with Indigenous peoples to assess marine safety risks in their communities. We are learning where we need more capacity to prevent and respond to marine emergencies. Multiple First Nations, including the Heiltsuk Nation, have proposed establishing Indigenous marine response centres as part of this process,” the statement read.

“Our discussions with the Heiltsuk Nation are ongoing.”

Kelly Brown is the director of the Heiltsuk Integrated Resource Management Department. Photo: Louise Whitehouse / The Narwhal

To mention nothing of the bungled cleanup, dozens of people like Campbell immediately lost their jobs in the clam beds, where 50,000 pounds of manila clams were harvested the year before the spill.

“The spill itself devastated our community,” Slett said. “We haven’t been able to harvest clams commercially since. And that has affected up to 50 families in our community.”

Out of work, Campbell started getting his first aid certifications and then enrolled in a two-year stewardship technician training program, which prepared him for a job with the Coastal Guardian Watchmen.

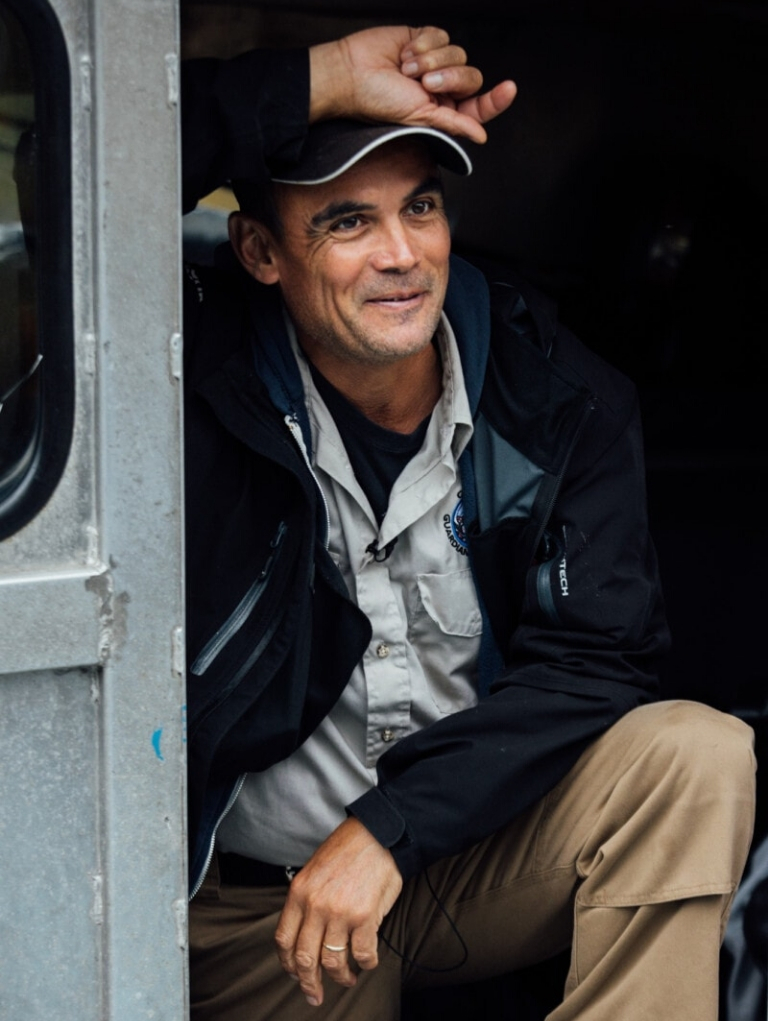

Walter Campbell is one of six Coastal Guardian Watchmen in Heiltsuk Territory. Photo: Louise Whitehouse / The Narwhal

Before the Nathan E. Stewart contaminated Gale Passage with diesel fuel, Campbell was a commercial clam digger in the area impacted by the spill. Photo: Louise Whitehouse / The Narwhal

As Campbell pilots the boat, I notice a red sticker by the steering wheel that says “Report More Pollution” alongside a 1-800 number for the Canadian Coast Guard.

If the Heiltsuk succeed with their proposal, help may actually be on hand next time someone reports a spill along this coastline.

“If we had that in the first place, maybe we’d have been able to protect more of this,” Campbell said.

Updated on Nov. 26, 2019, at 5:08 p.m. PST to include comment from Transport Canada.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On March 17, federal Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre...

Continue reading

B.C. previously allowed mineral claims without First Nations consultation. It was court-ordered to fulfill its...

British Columbia has vowed to fast-track several mining projects in an effort to blunt the...

Alberta introduced North America’s first industrial carbon tax in 2007. Now an industry email obtained...