Celebrating 7 years of The Narwhal — and gearing up for the next 7

Between a fresh take on engagement and our new life on video, our team is...

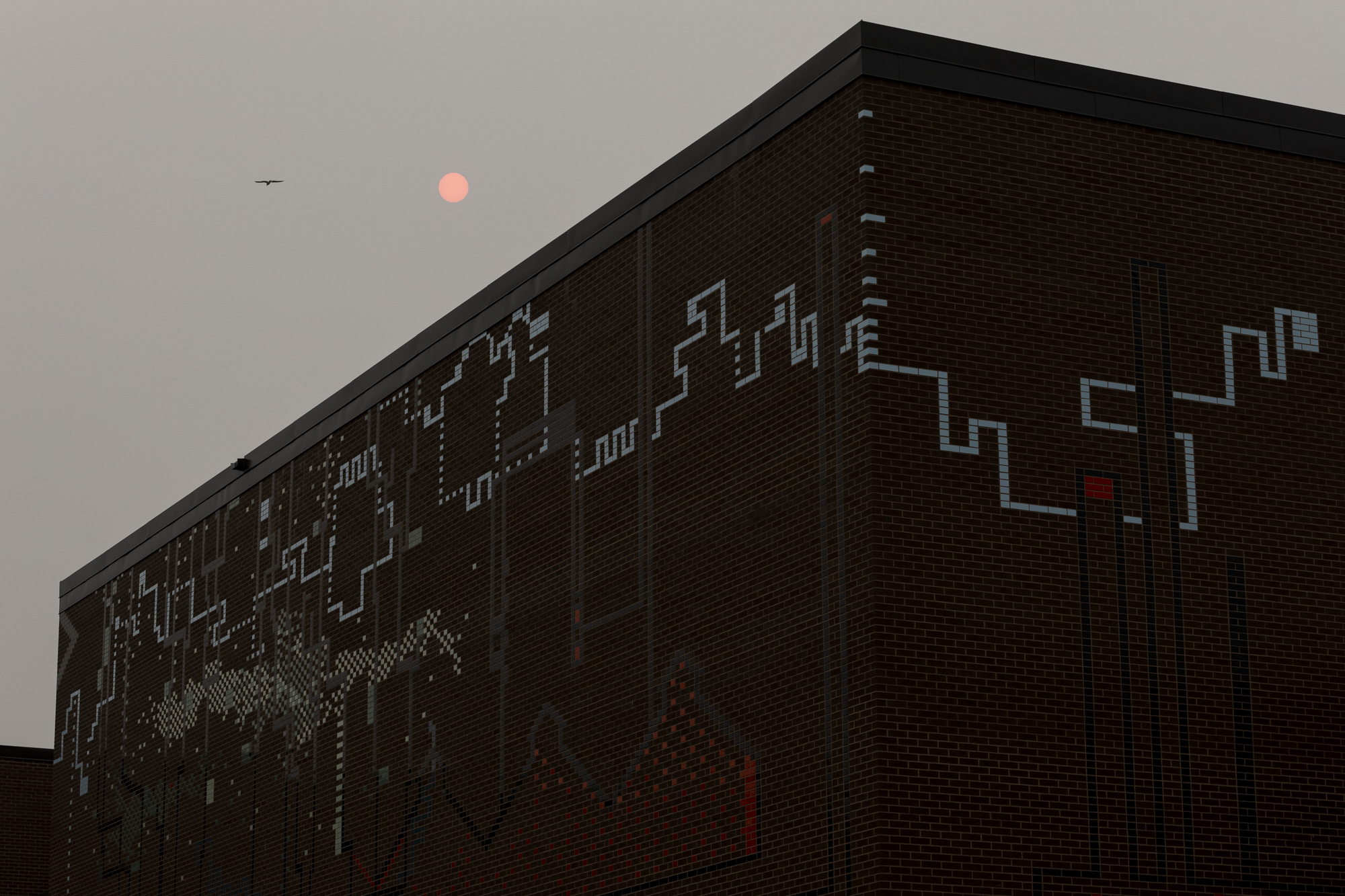

By the evening of Sunday, June 4, breathing the outdoor air in Peterborough, Ont., was like smoking seven cigarettes a day. While the haze seemed to be lifting by late Monday, enough even to unveil the sun, by Tuesday morning that red blazing ball in the sky said the smoke was all but cleared. The city smelled like a bonfire again on Wednesday.

Wildfires are burning across Canada, in particular out west, in Quebec and northern Ontario, devastating the communities closest to them and sending windborne smoke to far-off places. Eastern Ontario is being walloped, along with Quebec’s north shore and small pockets across the country.

When Julian Aherne saw Environment Canada’s air quality warning come through for Peterborough on Sunday, the Trent University associate professor quickly shut his doors and windows. He uses data and modelling to study the impacts of air pollution and other contaminants on natural environments. In other words, he knows exactly what it means when pollution levels jump from well under 20 micrograms per cubic metre of air on any given day, to reading over 150 micrograms — as they did that night in Peterborough. A couple days later, those figures soared over 180 micrograms per cubic metre locally, and twice that near Ottawa and around Kingston, which sat at 455 micrograms per cubic metre of air on Wednesday, June 7.

That high concentration of particulate matter becomes a concern when it’s made up of particles with a diameter of 2.5 microns or less: “So, small enough to get into your lungs,” Aherne explains. That’s where we get the measure of PM2.5 — particulate matter 2.5 — as is often cited as a component of air quality warnings, along with ozone and nitrogen dioxide. In high concentrations, like we’ve been seeing, many, many more of these tiny particles are able to make their way into our lungs.

A concentration of 22 micrograms per cubic metre of air of these tiny particles is about equivalent to smoking one cigarette a day, Aherne says. For the average person, this isn’t too significant, but when you consider how that higher concentration of particulate matter might affect children, the elderly and people with existing conditions, it becomes more of a concern.

We also don’t know what exactly is in the particulate matter that makes its way deep into our lungs, as it changes depending on the source. “We only look at the mass and volume. Here’s how much is in this volume of air, but that said, with the burning of forest fires, there’s trace elements, there’s black carbon,” Aherne says. “We could be receiving lead or mercury from the atmosphere. We don’t know the mix.”

But a major component of wildfire smoke is, of course, carbon: burnt wood.

The makeup of particulate matter in wildfire smoke can shift depending on the forest that burns and what those trees have absorbed from the atmosphere. “If the site was never burnt, it’s got a legacy store of woody material to burn. If it’s burned frequently, it’s relatively clean,” Aherne says. “If you think of a forest as a large receptacle that’s stored up over decades, you’ve got a richer pool that’s going to be reemitted.”

Mitch Meredith, a severe weather meteorologist with Environment Canada, was swamped with calls when we spoke this week. The unusual weather — that is, rampant wildfires in early June that sent billowing smoke into southern Ontario — was ringing alarms with people across the region.

“This year, as you know, we’ve already gotten into a drier period and had a melt of the snowpack early, so that allowed the forest to dry out earlier,” Meredith says. “Then what happened was a few fires got going in Alberta and then kind of shifted to Nova Scotia and now, for the bulk of it, we’re seeing the most number of forest fires right now in Quebec, in central Canada, and a few in northeastern Ontario.”

As of Wednesday, there were more than 50 fires burning in Ontario, of varying sizes.

Along with the early start to fires, Meredith says, another unusual thing happened. Winds from the south are more common this time of year in southern Ontario, but this week, wind is coming from the north and northeast, bringing down plumes of smoke from wildfires near and far.

“Dryness, then fires, then the wind pattern — it means widespread smoke started drifting across southern Ontario yesterday and got a bit thicker,” he says.

Petawawa, Ont., was also hard hit, with air quality reaching the categorically hazardous level of 300 micrograms per cubic metre of air. But most of the wildfire smoke appears to have settled in the south, blanketing southeastern Ontario and the Greater Toronto Horseshoe with air quality warnings; cancelling outdoor recess at schools in York Region and Hamilton, among others; and shutting down outdoor sports across Mississauga.

This, despite the nearest fire being hundreds of kilometres away.

“If you have a fire … the heat rises up quite quickly,” Meredith says. “So what happens further downstream is it settles. You can get an inversion, so it helps bring the pollutants near the surface and sometimes winds help to push the pollutants together in a process called convergence.”

That can cause heavy concentrations of particulate matter to settle over the ground hundreds or even thousands of kilometres away from the site of the fire. And depending on conditions there, warmer air aloft can trap cold air and smoke near the surface, aggravating the situation even further.

“It’s tricky with air pollution, it’s not just one thing. Unfortunately for Peterborough, a few things happened at the same time and a few things built up there from the forest fire smoke,” Meredith says. “We’re trying to stay on top of it but weather patterns, fires and heat, it’s all changing. A month ago, we didn’t know this would occur.”

Air quality degraded by wildfire smoke is uncommon in populated southern Ontario. It’s worrying, given the population size, but the severity hardly compares to the impact of wildfires on smaller, more northern communities across the country — especially closest to the fires. There, the impacts of poor air quality are combined with evacuations or the threat of evacuations, and such threats are a regular occurence.

Across Canada, about 200 Indigenous communities face a high risk of wildfires, according to Public Safety Canada.

Aherne, with Trent, notes that it isn’t always known how deeply air quality impacts some smaller northerly communities because it isn’t tracked as closely.

“There are many places between us that just don’t have an air quality monitoring station,” Aherne says. While a number of citizen science networks fill in some of the gaps left between government-funded monitoring, small and northern communities are still often left out. “The air quality network of Ontario, it’s great, I speak highly of that network, but that said, of course, it’s put in place to protect the public health, so the greatest density of network stations is where the greatest density of people is.”

In Ontario, provincial air quality monitoring stations reach as far north as Thunder Bay — roughly halfway up the province. About 24,000 people, 90 per cent of whom are First Nations, live above that line.

It’s also worth noting that the air quality readings facing southern Ontario this week are closer to an average day in some cities around the world. And in terms of southern Ontario on an average day, Aherne says, “Air quality is very good in Peterborough.” When his team is working on an air quality study, they head to Toronto where emissions from traffic offer a bit more to sample.

In the country’s biggest city, air degraded by exhaust and rubber tires also affects people unequally. Racialized and lower income people are more likely to be located near highways, and so more likely to develop pollution-related conditions such as asthma — subsequently putting them at higher risk when wildfire smoke permeates the air.

With so many factors at play, it’s hard to say whether these days of comparatively poor air are the new norm for southeastern Ontario — neither Aherne or Meredith want to say. But the oppressive smoke from wildfires, which are coming earlier and more frequently, along with the focus on respiratory health driven by the COVID-19 pandemic, have highlighted the value of our clean air: we aren’t accustomed to being able to taste and smell what we breathe.

“Air quality has a huge impact on life, much of that driven by particulate matter and what comes from forest fires is that concentration of particulate matter,” Aherne says. “What it does show us is that air quality is important to consider, we need to work harder at improving our air quality to reduce emissions from vehicles, and such, and realize that there are things we can’t control, like wildfires.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Between a fresh take on engagement and our new life on video, our team is...

The public has a few days left to comment on Doug Ford’s omnibus development bill....

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits