‘Afraid of the water’? Life in a city that dumps billions of litres of raw sewage into lakes and rivers

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

This is part one of a three-part series on Wood Buffalo National Park featuring photos by Louis Bockner, Sierra Club BC. Find the second story here and the third story here.

The Slave River races and tumbles over rose-coloured rocks at the Rapids of the Drowned in Fort Smith, Northwest Territories, as pelicans dive headfirst into the churning water, searching for lampreys and whitefish.

The river is the raison d’etre for small communities dotted along its banks. It is the reason Indigenous communities settled in the area, followed by fur traders and missionaries. It provides spiritual balm, recreation, fish and draws tourists to the remote region for paddle-boarding or viewing the most northerly nesting areas of American white pelicans.

But pollution and shrinking water flows are changing this river, which flows out of the Peace-Athabasca Delta in Wood Buffalo National Park. The Peace and Athabasca rivers wend their way from the dams of B.C. through the massive land disruptions of the Alberta oilsands to the park, a UNESCO world heritage site since 1983.

Wildflowers at sunset in Fort Chipewyan along the shores of Lake Athabasca.

White American Pelicans take a graceful flight above the Slave River near Fort Smith, N.W.T. The birds fly North from their winter homes in the Gulf of Mexico to spend their summers in Canada’s north.

Calypso orchids, also known as fairy slippers, near Fort Smith, N.W.T.

Forest flowers. Fort Smith, N.W.T.

Roughly 230 kilometres south, swerving through the channels of the Peace-Athabasca Delta, Kevin Courtoreille looks at the banks of grasses and willows and shakes his head in disgust.

“Five years ago there was none of this here. The lake was wide open and the water was clear,” he said, digging an oar into shallow, murky water, then shaking off mud before being forced to stop and backup to clear the boat engine of weeds.

“This will be Mamawi Creek, not Lake Mamawi, in maybe 20 or 30 years. It’s kind of scary,” said Courtoreille, who has spent his life in the northern Alberta hamlet of Fort Chipewyan, and now works as a technician testing the delta’s water, plants, wildlife and sediment for Mikisew Cree First Nation’s community-based monitoring program.

The Peace-Athabasca, one of the largest freshwater deltas in the world, is facing a perfect storm that will not only change the geography, but also the way of life for people who, for generations, have lived off the land, trapping, hunting and fishing. UNESCO is considering adding Wood Buffalo to the list of World Heritage Sites in Danger because of threats such as oilsands development and hydro dams.

Map of threats to Wood Buffalo National Park from UNESCO report.

There is general consensus that problems started with B.C.’s WAC Bennett dam, constructed on the Peace River in 1968 before federal environmental assessment guidelines existed. The WAC Bennett dam — one of world’s largest earth-filled dams — was followed by the Peace Canyon dam in 1980.

As the reservoir filled behind the Bennett dam, parts of the delta dried up and, afterwards, levels never reached their former heights, said Courtoreille pointing to a line on the Lake Athabasca rocks which show water was several feet higher in the past.

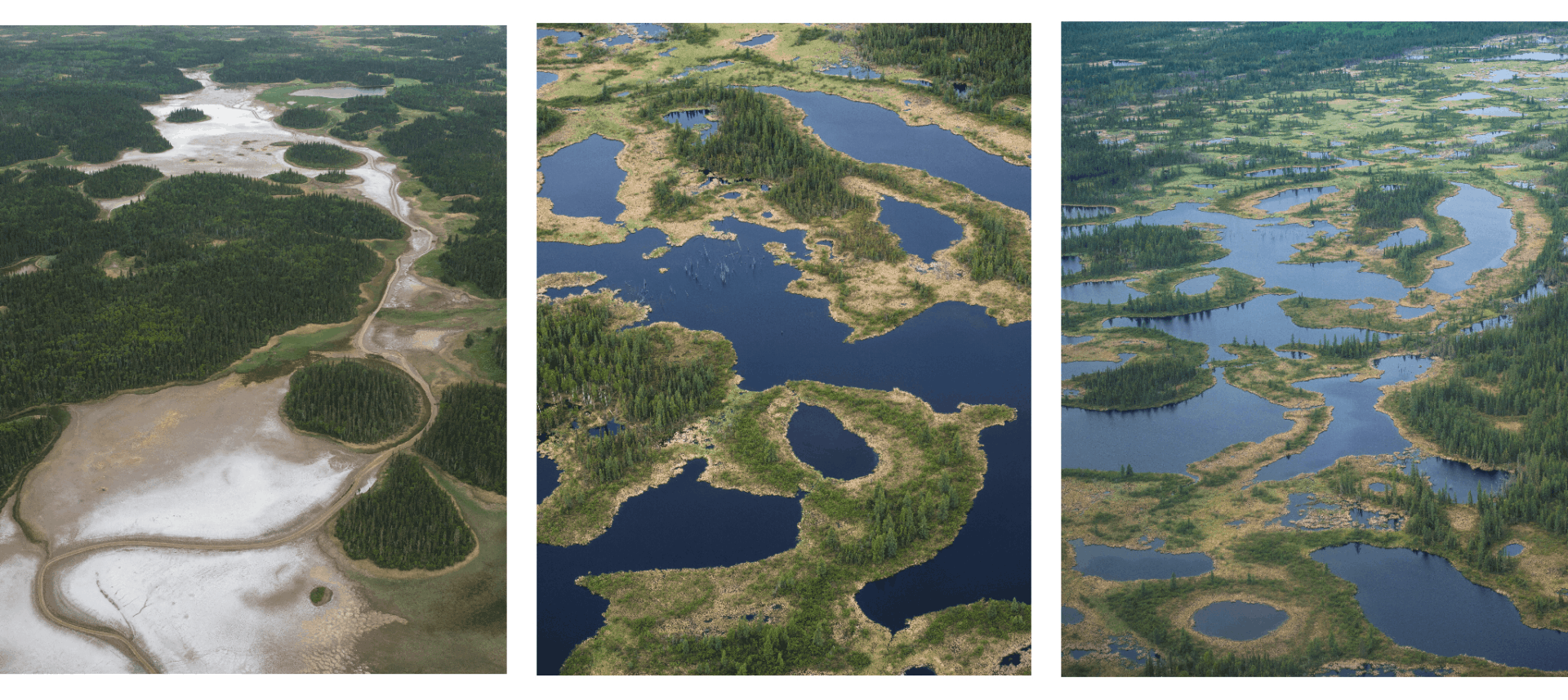

Spring floods changed because the dams stopped the formation of ice jams that previously forced the water to back up into the delta and, a flyover of the delta showed that, even though the water is higher than usual this spring, small ponds and streams remain obstinately dry.

Far left: Wood Buffalo National Park salt plains. Centre and right: Aerial view of Wood Buffalo National Park’s famed wetlands.

Cracked earth details in Wood Buffalo National Park’s Salt Plains Outlook trail.

From the air, the stretches of boreal forest give way to chains of small lakes, with rivers meandering through marshland towards the watery expanses of the delta, but stretches of bright yellow grasses and empty channels show dry areas.

That means hunters are unable to get to traditional hunting grounds and animal populations are changing.

Mikisew Cree First Nation elder George Sloan Whiteknife, who has been guiding moose hunts for 30 years, pointed to where, last fall, a mud bar appeared slap in the middle of the lake.

“We can’t get anywhere now,” he said.

Then, there are the recurring stories about damage and dangers when BC Hydro periodically releases water.

Mikisew Cree Chief Archie Waquan used to trap, but, with drying of the delta and the additional complication of unexpected releases of water, he believes it is no longer a viable way to earn a living.

Chief Archie Waquan of the Mikisew Cree First Nation, in Fort Chipewyan, Alberta.

“We would set our traps and they would let go all the water and we would lose all our traps and all the creatures like beavers burrowing on the banks, when the water comes up, they are dead,” he said, reflecting on how the community is being forced to change its way of life to meet the new reality.

Climate change, natural sedimentation and pollution from rampant development of the Alberta oilsands play a role in the changing delta and another factor is post-glacial rebound — the slow lifting of the lake bottom after the end of the ice age.

Also, the Peace and Athabasca rivers flow into the delta and, as oilsands development surges ahead industry withdrawals from the Athabasca River are increasing, with current figures hovering around 111.5 million cubic metres of water annually.

But dams on the Peace River remain in the crosshairs as the major culprit and fears are growing about what will happen when Site C, the third dam on the Peace River, is built.

These concerns don’t seem to sink in for provincial and federal governments considering projects such as Site C or the massive Teck Frontier oilsands mine proposed for 30 kilometres south of Wood Buffalo Park, said Melody Lepine, government and industry relations director for Mikisew Cree First Nation.

Lepine knows from studies and the stories of elders how much water levels in the delta dropped after the Bennett dam was built in 1968, followed by the Peace Canyon dam in 1980, and, like those who rely on the delta and the surrounding land for trapping, hunting and fishing, she fears the changes what Site C will bring.

“Site C is a huge concern because of the problems the Bennett dam caused and the neglect from BC Hydro and the B.C. government in not recognizing downstream impacts,” said Lepine, who presented countless submissions to try and ensure downstream impacts on the delta were recognized and incorporated into the Site C environmental assessment.

Aerial view of river in Wood Buffalo National Park.

The Athabasca River near Fort McMurray.

A heavy hauler truck in an open pit mine in the Alberta oilsands.

Alberta’s oilsands North of Fort McMurray.

The Joint Review Panel’s report on Site C concluded “there would be no effect from the project on any aspect of the environment in the Peace Athabasca Delta and a cumulative effects assessment on the PAD is not required.”

Parks Canada asked for a cumulative effects study of dams on the Peace River during Site C hearings, but BC Hydro has consistently claimed there is no effect on the delta 1,100 kilometres downstream.

BC Hydro spokeswoman Mora Scott said leading experts were called to evaluate potential downstream effects of Site C.

“In all cases, the studies concluded that the project would have no notable effect on the Peace-Athabasca Delta (PAD), which is located 1,100 kilometres downstream of the project,” she said.

Indigenous concerns were basically dismissed, Lepine said bleakly.

Now, the push for consideration of cumulative effects of the dams and climate change is gaining momentum however with the release of the Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) of Wood Buffalo National Park.

The assessment was demanded by UNESCO after the Mikisew Cree petitioned the World Heritage Committee to have the park added to the list of World Heritage Sites in Danger and a monitoring visit by World Heritage Committee inspectors confirmed risks faced by the park.

The assessment is a stepping stone to the action plan, which has to address 17 recommendations and is scheduled to be completed by Dec. 1.

Mikisew Cree man tying up a motor boat in Fort Chip, AB.

Stop sign in Fort Smith showcasing indigenous languages alongside French and English. Fort Smith, NWT.

Improving identification and management of cumulative effects is a priority, says the assessment, which concludes that dams on the Peace, combined with climate change have changed the delta.

“Flow rate changes on the Peace and reduced seasonal flows on the Athabasca, in conjunction with climate change, have decreased water levels and the extent of open water in the Peace-Athabasca Delta,” it says.

Land users say they no longer feel it is safe to drink the water or eat the fish and the report acknowledges problems, pointing out that without the springtime flush of water through the delta, water can become stagnant.

“Mercury has also been found in high levels in fish and bird eggs, so consumption limits were set by the government, further limiting access to food sources and further eroding confidence in local food sources,” the report states.

The assessment uses existing research to project potential changes to the delta due to climate change and, unsurprisingly, it’s bad news.

Parks Canada spokesman Tim Gauthier said in an emailed response to The Narwhal that warming over the next 30 years is likely to affect ice quality, ice jam flooding events and water flow into the delta.

“Anticipated increases in air temperature may also produce mid-winter thaws, which could cause winter flows to increase from current levels and have a negative impact on ice quality, both in terms of safe travel across (the ice) and in the structural quality of the ice,” according to the assessment.

Bruce Maclean of Maclean Environmental Monitoring, who has worked with Mikisew Cree since 2007, is disappointed the assessment does not look at cumulative impacts, especially with Site C and the massive Teck Frontier oilsands proposal on the horizon.

“The situation is bad to the point we are compromising the entire Peace-Athabasca Delta. New projects coming on board are going to further exacerbate that problem. We may want to stray away from them until we rectify the problems we have already created,” he said.

The delta is silting up, there is glacial uplift and climate change impacts — which are all natural elements, Maclean said.

But the unnatural aspects are regulation of water from dams on the Peace River, meaning more water in the winter and less water in the summer, plus increasing withdrawals from the Athabasca River by the oil and gas industry.

What is now needed to help the delta is a commitment to manage flows on the Peace and Athabasca rivers to bring water back to the delta, he said.

Changes documented through the monitoring program include large declines in muskrat and waterfowl populations, changes in water quality and flow, changes to ice and changes in the timing of flooding, Maclean said.

One of the projects now underway is a study of muskrat declines and it is is not only the demise of the trapping industry that makes it important to study muskrat populations, Maclean said.

“Muskrats are a sentinel species. If you have good floods you have a lot of habitat and great muskrat populations. If you have healthy muskrats you have a healthy delta,” he said.

For Fort Chipewyan residents, a major concern is the state of the ice because, as soon as the ice is thick enough, the winter road opens across the lake, allowing goods, from groceries to fuel, to be driven to the community.

Once the ice road is closed all goods come by air, meaning sky-high prices.

In The Northern, the only grocery store, a two litre carton of orange juice sells for $11.29, butter for $8.19 and a litre of Coke for $5.25.

A new grocery store, run by Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation, is due to open shortly and there are hopes of bargains, but the ice road will continue to be an essential supply link.

“You stock up on dry goods. Sugar, lard and things like potatoes, so you don’t have to buy anything except veggies,” said Mikisew Cree elder Basil Tourangeau.

But fluctuating water levels through the winter, combined with climate change, means the ice does not freeze in the same way as previously and is being eroded from underneath, Maclean said.

“You’re getting worse quality ice. Not strong blue ice,” he said.

Changes to the rivers around Wood Buffalo National Park are becoming more noticeable each year, said Ernie Tourangeau, as he spent a leisurely Sunday afternoon fishing with his family from a sandy beach beside the Salt River, a tributary of the Slave.

Whether it is climate change, pollution or dropping water levels, the fish are not the same as they used to be, Tourangeau said.

“Some of the fish you just wouldn’t bother with. The white fish are just scaleless and pink because of what is coming down the river,” he said.

It is a view supported by scientific studies.

A 2014 peer-reviewed study by the University of Manitoba linked oilsands pollution to elevated cancer rates in Fort Chipewyan and researcher Stephane McLachlan said the health effects on communities downstream of oil and gas development is clear.

The study found that fish and animals consumed as part of a traditional diet contained unusually high concentrations of contaminants, such as heavy metals, released during the extraction of bitumen and that health problems such as diabetes were then exacerbated as residents switched from a traditional diet to processed foods.

“The results of this study, as they relate to human health and, especially, the increasing cancer rates, are alarming and should function as a dramatic wake up call to industry, government and communities alike,” McLachlan said in a news release.

Journalist Judith Lavoie interviews Mikisew Cree member Robert Grandjambe. Fort Chip, AB.

Robert Grandjambe pulling a lake trout from his nets in Lake Athabasca near Fort Chip.

George Sloan Whiteknife, Mikisew Cree elder, in Fort Chip, AB.

Leaves at sunset near Pine Lake in Wood Buffalo National Park.

Those who catch their own fish are warned to eat only two portions a week because of mercury contamination and elders are told to limit the amount of moose organ meat they eat, Courtereille said.

Those are vast changes for a community that, until three decades ago, relied on the land and water for food and for earning a living.

For some, with Site C and Teck looming, hopes are dim that even recommendations from the World Heritage Committee can restore what is being lost.

Becky Kostka, land and resources manager at Smith’s Landing First Nation and project director of the Slave River Coalition, a Tides Canada initiative to protect and restore the Slave River, worries about the future.

“We just feel Site C will be the final nail in the coffin of the Peace Athabasca Delta,” Kostka said, swatting at the ever-present mosquitoes as she stood on the smooth rocks watching the river.

“Last summer, the water dropped so low there were visible rocks no one had ever seen before. There was a new set of rapids.”

Add in climate change, with warmer winters and, for a few short months of the year, hotter, drier summers and the possibility of disaster mounts.

“There are some words in the Dene language that are not used anymore because the ice doesn’t make the same noise,” Kostka said.

Industry should come and look at what they have done, said Athabasca Chipewyan elder and land-user Alice Rigney.

“You don’t deal with Mother Nature like this. She knows what she is doing and I can hear her crying.”

This is the first part of a three-part series. Read the second story here and the third story here.

The Narwhal’s reporter Judith Lavoie travelled with Sierra Club BC campaigner Galen Armstrong and Sierra Club BC photographer Louis Bockner to Wood Buffalo National Park in early June. Lavoie’s travel expenses were paid by The Narwhal, with the exception of a flyover of a section of Wood Buffalo National Park, for which she snagged an empty seat in the plane.