5 things to know about Winnipeg’s big sewage problem

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits

In October 2020, John Henry received an unexpected phone call from the Ontario minister of environment’s office asking for a meeting with no stated agenda or topic of discussion.

Henry, the elected chair and CEO of Durham Region, thought he would be talking with the minister — then Jeff Yurek — but it was Yurek’s chief of staff on the line who informed him the government wanted to “bring the big sewage pipe that was going to go into Lake Simcoe into Durham Region.”

Henry, formerly the mayor of Oshawa, was surprised. This was the first time he, or anyone, was hearing of the government’s alternative solution to a heated debate over a new sewage facility that has lasted over a decade. The issue has been divisive for 17 municipalities across two regions east of Toronto: Durham, a region of almost 700,000 people at the very east end of the Greater Toronto Area, bordering Lake Ontario; and York, a region of over 1.17 million people between Toronto and Lake Simcoe.

Since 2009, York Region has spent $100 million of the $715 million budgeted for a proposed wastewater treatment plant that has been stuck in limbo. Called Upper York Sewage Solutions, the project was supposed to be a component of provincial growth projections, which estimate York Region will expand to nearly double its population by 2051. Without increased sewage capacity, the towns of Aurora, Newmarket and East Gwillimbury say they will have to halt all development soon.

York Region says the new plant is designed to use “leading edge” technology to turn 40 million litres of wastewater per day into purified, clean water before it heads into Lake Simcoe. The most concerning pollutant in treated sewage is phosphorus, an increase in which can spur the growth of algae blooms that create toxins harmful to human and animal health. Not everyone is convinced that risk can be adequately reduced. Upper York Sewage Solutions has garnered years-long opposition from municipalities, the Chippewas of Georgina Island — whose 923 residents have been on a boil water advisory since 2017, and source their drinking water largely from the lake — and environmental organizations like the Rescue Lake Simcoe Coalition.

Opponents argue the 2014 environmental assessment — the most expensive one the region has ever conducted, at $25 million — was flawed: it lacked a long-term perspective on the impacts of projected population growth on the watershed and didn’t include the traditional knowledge of Georgina Island First Nation.

The green light needed to begin construction on Upper York Sewage Solutions has been stalled time and again as successive provincial governments hedged, delaying the proposal and approvals for environmental assessments while avoiding making a decision altogether.

In October 2020, the Ford government seemed to have a different idea, as Henry learned in that phone call. Instead of creating a new facility that would dump sewage in Lake Simcoe, its plan was to expand the sewage lines from York Region to reach the existing high-tech Duffin Creek Water Pollution Plant in Pickering, which releases treated water into Lake Ontario. That plant is jointly operated by York and Durham regions.

“Of course, we said no,” Henry told The Narwhal in early March. Durham Region is growing just as quickly as York Region, he added, and needs sewage capacity to serve its residents first.

Henry’s refusal led to a meeting with then-environment minister Yurek. The government wanted a resolution, Henry said, and asked him to sign a non-disclosure agreement to keep conversations private. Henry refused that too, taking the issue straight to council for debate. “They spent 10 years on this prior to calling us and all of a sudden they wanted us to solve it right away in 2020. That’s not right or fair,” he said. (A spokesperson for York Region said it did agree to a non-disclosure agreement that “protects the confidentiality of exploratory discussions.”)

After that, discussions about the project got “long and convoluted,” as the government tried to navigate back and forth between the growth needs and concerns of two large regions. Durham Region doesn’t want York Region’s sewage. Henry said that Durham supports York Region’s resolution to build the plant at Lake Simcoe, with all the checks and balances that protect the environment. “The challenge is all the time and all the investment that’s been made so far,” Henry said.

York Region begins working on the Upper York Sewage Solutions Project to accommodate 153,000 additional residents. The new project would replace existing sewage lagoons with a new facility that would dump into Lake Simcoe.

The former Liberal government approves the project pending an environmental assessment. York Region begins a multi-year process of studying the project and conducting community consultations.

The project’s environmental assessment report is submitted to the provincial Ministry of Environment and Climate Change for approval.

Ministry staff complete their review and find York Region met all the requirements, except consulting with the Chippewas of Georgina Island First Nation.

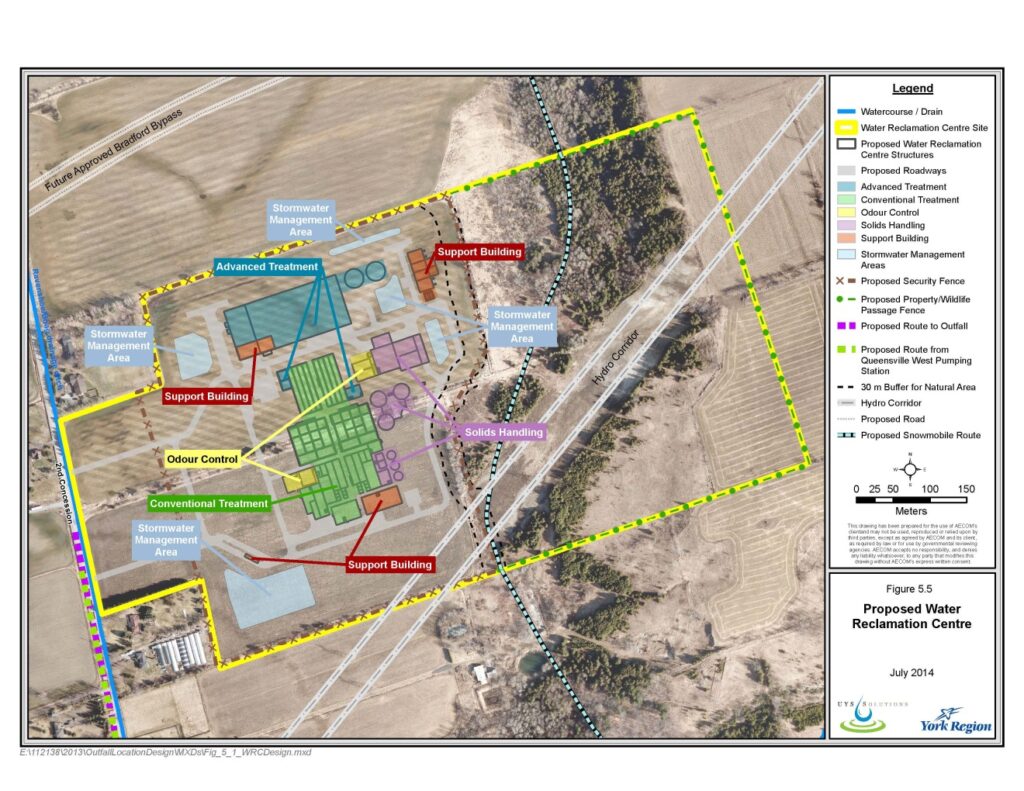

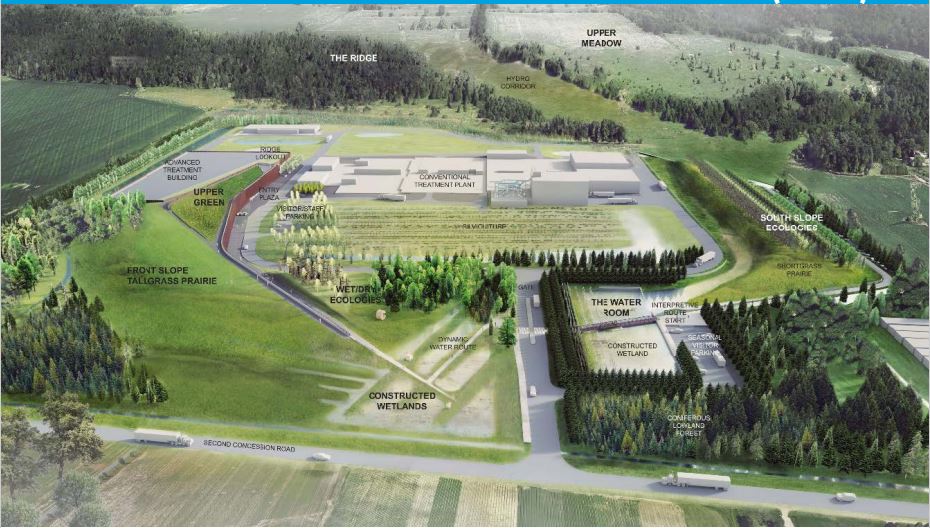

To this day, the project remains in limbo 13 years after it was first proposed, with the provincial government saying it might not have a solution for a region that desperately needs more sewage capacity until after the 2022 election. Meanwhile, York Region recently green-lit development for future growth on 1,400 acres of protected Greenbelt farmland. The facility itself would require additional Greenbelt land to be re-designated for development adjacent to a hydro corridor and the future approved Bradford Bypass.

All of this has put Upper York Sewage Solutions at the core of Ontario’s ongoing debate over how to best serve a rapidly growing population without harming local, surrounding watersheds — or as Conservative MPP Toby Barrett described it in October 2021 remarks as the tension created by “overpopulation and pollution.”

Henry says the problem needs to be addressed carefully. “It is important for both Durham Region and York Region and you only get one chance to do it well,” he said. “There’s been a lot of time and money spent on this and a lot of reports have been written. Whatever is decided needs to be the right decision.”

But opponents say this saga is an illustration of serious government ineptitude. “Hell’s going to freeze over before the government of Ontario solves this problem,” said Claire Malcolmson, executive director of the Rescue Lake Simcoe Coalition.

Over seven years have passed since York Region sent its environmental assessment report to the province for approval. It took the then Liberal-led Environment Ministry three years to review the findings and consult stakeholders. Then came a change in government, with the election of Doug Ford’s Progressive Conservatives in 2018. Shovels went into the ground to prepare the site in June 2019, even as York Region awaited the province’s approval of the facility’s systems to clean and discharge wastewater.

A year later, in July 2020, then-environment minister Yurek sent a letter to York Region Chairman Wayne Emmerson stating the province was considering alternative sewage solutions, like creating pipelines to the Durham facility. Then came Yurek’s conversation with Henry. In June 2021, despite Durham’s opposition, Yurek introduced the York Region Wastewater Act, meant to “gather up-to-date information on environmental, social and financial implications of any wastewater solution for the region.” The bill proposed to disregard the 2014 environmental assessment and set up a five-member advisory panel to review the whole project, as well as alternative options including sending York sewage to the Durham plant.

That fall, David Piccini re-introduced the bill after taking over as the Progressive Conservatives’ third environment minister, telling the provincial legislature that more engagement was needed with First Nations and other stakeholders “to get this right.”

The bill was fast-tracked and voted through without much discussion or debate, putting the fate of the facility into the hands of the advisory panel, which is expected to release the results of its investigation by fall 2022. (The act also indemnifies the government from being sued for any lack of action taken in respect to the project.)

The Chippewas of Georgina Island First Nation has opposed the project. Though the former Kathleen Wynne-led Liberal government said it included the First Nation in early stakeholder sessions, the nation said it found out about Upper York Sewage Solutions through media reports, not from the Ontario government. The plant is designed to run into the Holland River at the south end of Lake Simcoe, which opens into the waters surrounding one of the three islands home to the First Nation.

Shovels go in the ground as York region waits for approval on the entire project, which includes a wastewater facility and phosphorus off-setting program.

Ontario’s environment ministry advises York and Durham regions that the government is considering alternative options. These include connecting York’s sewage system to Lake Ontario via a pipe running through Durham Region to the Pickering wastewater plant.

The Ford government introduces and hurriedly passes the York Region Wastewater Act, sets up an expert advisory panel to review the whole situation.

York Region is told that no decision will likely be made until after the provincial election.

The nation’s environmental coordinator Brandon Stiles said that his community has “never ever been properly consulted.”

“What we have gotten is usually information where decisions have already been made by York Region or the ministry,” Stiles said. “And it’s like a quick technical run by, ‘oh, by the way, this is what we’re doing.’ … We’re not brought into the right levels of decision-making. It’s not a meaningful approach whatsoever.”

Stiles said the nation also learned about the Ford government’s panel through media reports, but he is hopeful it will help move the consultation process in a meaningful direction. The province has assured the nation that it will include Indigenous consultation. Stiles sent the environment ministry a list of questions about the panel’s mandate, also asking how members were selected. He hasn’t received a response yet but Environment Minister Piccini did send him an invitation to speak to the panel, which, Stiles said, is a change in pace.

“We’re not willing to watch a project be developed that’s going to destroy a fish habitat around the Island … that’s our major food source …,” said Stiles. Piccini told The Narwhal the panel “will absolutely be engaging with Georgina Island First Nation.”

Lake Simcoe is the largest inland lake in southern Ontario and provides treated drinking water for seven communities, not including the nation. The surrounding watershed is already at risk of high levels of phosphorus and chloride pollution from fertilizers used on nearby farms, as well as from sewage dumping. It’s meant to be protected by the Lake Simcoe Protection Plan, one of the strongest watershed protection legislations in the province, which prevents any new sewage plants from being built on the lake, permitting only expansion and improvements of existing plants.

When the environmental assessment applications were submitted in 2014, phosphorus loads were 71 tonnes per year, much higher than the 44 tonnes per year set out in the plan. As of the Environment Ministry’s last 10-year report on Lake Simcoe, released in 2017, that number had increased to 131 tonnes per year.

The ministry is presently calculating the current levels of phosphorus but Malcolmson, of the Rescue Lake Simcoe Coalition, said the trend is clear. “Lake Simcoe is not healthier now than it was in 2009 when the plant was first proposed,” she said, making it unclear why the new facility is still being considered.

Any new wastewater facility would have to include stringent technologies to minimize additions to the already high level of phosphorus discharged into Lake Simcoe, but that will be expensive. In her 2017 annual report, Ontario’s then-environmental commissioner Dianne Saxe said the high cost of the treatment plants required to meet the standards in the Lake Simcoe watershed were “out of proportion to their environmental benefit.” Malcolmson said York Region has “technological optimism” in touting that leading-edge innovations will protect the lake.

The many nuances to local and regional environment policies are dividing the nine municipalities in York Region.

In November 2020, for example, the Town of Georgina council voted on a resolution asking the province to cancel the sewage plant, reimburse York Region for the money invested in it and work with the Chippewas of Georgina Island to find an alternative solution.

Others are working with the province to make the Upper York proposal work somehow. East Gwillimbury would be the site of the new facility if it’s built: a spokesperson for Mayor Virginia Hackson told The Narwhal in an email that Hackson had “a lengthy meeting” with the expert panel and is “actively engaged” in their discussions.

“Mayor and council are pleased that this panel has been established to identify the need for additional sewage service capacity and to provide alternatives to providing the additional capacity to accommodate future growth of both York and Durham,” Hackson’s spokesperson said. “They look forward to continuing discussions and the final report and recommendations.”

The expert panel is tasked with offering advice on all options for providing additional sewage capacity to both York and Durham regions, taking into consideration costs, sustainability and efficiency of each one in protecting human health. Little information has been shared about how the five panel participants were selected; none of the panel members responded to The Narwhal’s interview requests.

If the panel decides to side with the province and allow York Region to transport its sewage to the Pickering plant and Lake Ontario, that would mean running a pipe through the protected Oak Ridges Moraine. If the panel decides to let Upper York Sewage Solutions be built as proposed, that might risk the health of shallower, smaller Lake Simcoe.

Both watersheds would likely be affected by the addition of phosphorus and personal care products flushed into the sewage system.

Onlookers and residents say the sewage facility saga is ripe election fodder. Piccini blames the previous Liberal government for failing to make a decision on the project, pointing the finger directly at both former Liberal premier Kathleen Wynne and current Liberal leader Steven Del Duca.

“The data behind it was left to go stale by the previous Wynne-Del Duca government. They had the application, sat on it so long, and made that change [to the terms of reference] in 2010 with very little to no consultation. It’s been stale for a decade,” Piccini said. Last year, Ford expressed sympathy with York Region for being stuck in a growth-planning limbo, agreeing that the sewage project had dragged on “forever.” All of York Region’s provincial representatives are Progressive Conservative MPPs, including six cabinet ministers.

Opponents of the government are quick to note that the Progressive Conservative government’s approach to this project is full of contradictions. While it has deemed the 2014 environmental assessment for the treatment plant to be out-of-date, the government is also arguing that a new environmental assessment is not required for the Bradford Bypass, a proposed new highway just north of the Moraine through the protected Holland Marsh, even though the assessment was completed in 1997.

Meanwhile, in multiple council meetings last year, York Region Chairman Emmerson repeatedly called on councillors to stick to their guns and push the province for the new treatment plant, since the region has already spent $100 million, most of it on buying the land.

Emmerson refused interview requests, despite almost every York Region mayor referring The Narwhal to his office for more information on this issue.

Piccini told The Narwhal the advisory panel will give its advice to him “or whoever is the minister of environment after the election.” He expects a decision to be made soon after.

Malcolmson believes there’s hesitancy to make a decision on this project because “once this is done, this will be a mark on this party and it will be negatively perceived by people around Lake Simcoe, with good reason.” Between the non-disclosure agreement and broader politics, the lack of transparency and clear answers worries her.

“My hope is that they listen to that worry — that they make a decision just not to put a new sewage treatment plant on a lake teetering on the edge of hell,” she said. “At the end of the day the simplest answer would be to recognize there are limits to growth. We can’t just grow anywhere and ignore the impact on the environment.”

Updated on March 17, 2022 at 8:57 a.m. ET: This story was updated to reflect that the Bradford Bypass will cut through the Holland Marsh, which falls within Ontario’s protected Greenbelt, rather than the Oak Ridges Moraine, which is just south of the proposed highway.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits

Climate change, geopolitics and business opportunities power a blue economy

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...