A massive Rockies real-estate project wins another court battle. Opponents will keep fighting it

Residents and nearby First Nations wanted a new environmental impact assessment of the contentious project....

The Yukon government has rescinded approval of a controversial resource road that would have opened ATAC Resources’ access to vast mineral claims in the Beaver River watershed.

A spokesperson with Yukon’s Department of Energy, Mines and Resources confirmed the decision Monday in an email to The Narwhal.

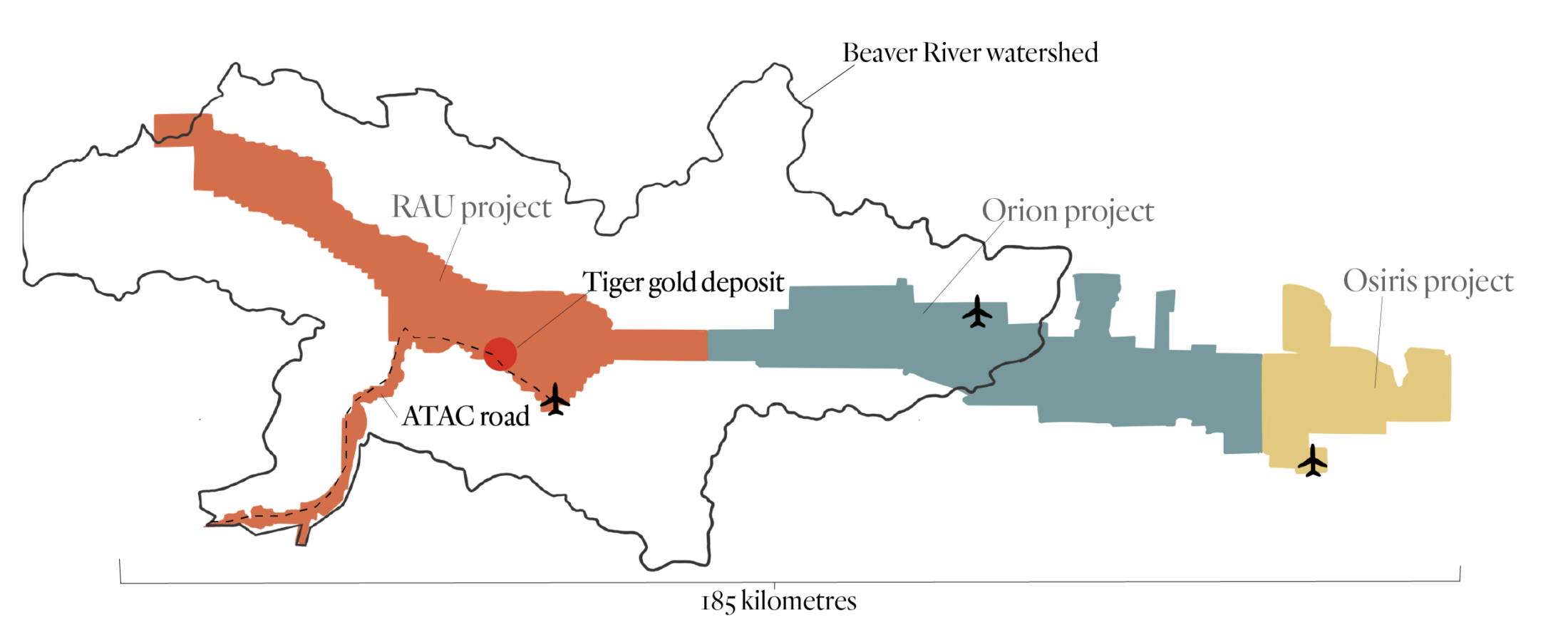

The 65-kilometre ATAC road, which was given a conditional green light by the Yukon Environmental and Socio-economic Assessment Board in 2017, would have created all-seasons access to a portion of the company’s three mineral claims that form the Rackla gold property. The new route would have connected Keno City to the Tiger gold deposit, the site of a proposed open-pit gold mine where ATAC Resources hoped to produce 268,000 ounces of gold.

Those who worried the road would have opened an undisturbed watershed to scalable development welcomed the news.

“I am ecstatic,” Randi Newton, conservation manager with the Yukon chapter of the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society (CPAWS), told The Narwhal. “I’ve hoped for this outcome for many years, and it’s a relief that it’s finally here.”

“What this decision does is remove a major looming threat to the environment of the Beaver River watershed and it creates the opportunity to set down a sustainable vision for that watershed,” Newton said.

ATAC Resources, a Vancouver-based exploration company, is seeking legal counsel regarding the decision, according to Andrew Carne, the company’s vice-president of corporate and project development.

“ATAC does not agree with many material aspects of the government’s decision,” Carne said in an email to The Narwhal. “The Tiger gold deposit remains a high-quality advanced-stage exploration asset with significant value to be unlocked.”

A spokesperson with Energy, Mines and Resources said the department was unable to immediately provide comment.

Location of ATAC Resources Rackla gold property in Yukon. Map: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

The proposed ATAC road would have provided an initial entrance to the company’s 185 kilometres of mineral claims and exploratory projects. During the road’s assessment and eventual approval by the Yukon government in 2018, many conservation groups and Yukoners expressed concern the road would act as an invitation to further industrial incursion in the watershed.

ATAC Resources currently accesses its claims through a series of trails and by air, making exploration work costly.

A map showing ATAC Resources’ three Rackla gold properties and the location of their airstrips.The ATAC road would have provided 65 kilometres of access to the company’s mineral claims within the Beaver River watershed but those claims extend for a total of 185 kilometres. Map: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

The prospect of a new road caused concern for the CPAWS, which noted easy access could lead to an avalanche of new development proposals, none of which were considered as part of the proposed route’s cumulative impact when it was approved.

The road flamed frustrations that mineral development is allowed despite the absence of completed land use plans. In a recent public engagement process conducted by an independent review panel, participants pointed to the ATAC road as an example of Yukon’s failure to consider the cumulative impacts of mining and industrial development on the landscape.

A report released by the panel found the road “was used as an example of a poor consultative process, where free entry staking was used for the purpose of creating road access to a property against the wishes of the First Nation and community.”

The panel found the road’s approval led to the retroactive creation of “a sub-regional land use planning process outside of Chapter 11, with the assumption made by many that the future road would be part of the plan and the landscape.”

One participant told the panel, “This is planning done entirely backwards and driven by private industry action without consideration of actual community- and Indigenous-driven processes.”

The sub-regional land use plan for the Beaver River watershed was conducted by the Yukon government and the Na-cho Nyäk Dun First Nation, on whose territory the ATAC Resources’ gold claims are located.

Without the ATAC road, some hope the sub-regional land use plan can be scrapped for a broader land use plan that will encompass the entire Beaver River region.

“What this has done is create space to develop a land use plan that’s right for the region, that respects the long relationship that the First Nation of Na-cho Nyäk Dun has with the land, that respects the ties that Yukoners have to the Beaver River and respects the wild creatures that live there,” Newton said.

Na-cho Nyäk Dun Chief Simon Mervyn didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment.

Roads can literally slice and dice the environment, affecting the habitat and ingrained migratory patterns of wildlife. The Beaver River watershed is home to moose, wolves and grizzly bears.

The ATAC road would have crossed through wetlands and over rivers, potentially disrupting otherwise intact ecosystems, Newton said.

She added the road would have introduced a cascade of impacts to the watershed, including opening up the region to new hunting pressure.

“There’s beautiful salmon habitat in the Beaver River watershed that could have been impacted,” Newton said. “This 65-kilometre road was very likely the start of what would have been a very long road network.”

CPAWS recently released a report that cautioned the assessment board against approving road projects before land use plans are completed.

A porcupine climbs over a concrete safety barrier on the outskirts of Whitehorse. Photo: Malkolm Boothroyd

“Land use planning can take that broader view of how much development is allowable in an area, which areas should we keep remote and free of roads,” Malkolm Boothroyd, the report’s author and campaigns co-ordinator at the Yukon chapter of CPAWS, told The Narwhal in a previous interview.

“I think we’re hoping that Yukoners will talk about it and figure out how many roads there should be in this territory and what areas we want to keep road-free,” he said.

“I think what’s very special about the Yukon is that there are still areas that you can’t drive to. That’s incredible habitat for caribou and grizzly bears and that’s really rare in this day and age.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On March 17, federal Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre...

Continue reading

Residents and nearby First Nations wanted a new environmental impact assessment of the contentious project....

Growing up, Christian Allaire loved spending summers with his cousins in his grandma’s backyard, near...

B.C. previously allowed mineral claims without First Nations consultation. It was court-ordered to fulfill its...