Hope for a huge, ancient and imperilled fish

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...

In 1973 Elijah Smith, former chief of Champagne and Aishihik First Nations, travelled to Ottawa with a delegation of First Nations leaders to present then-prime minister Pierre Trudeau with a now-historic position paper.

“We are not here looking for a handout. We are here with a plan,” Smith famously said to Trudeau.

Smith was tired of First Nations being treated “like squatters in their own country.”

“We want to take part in the development of the Yukon and Canada, not stop it,” the paper Smith presented stated. “But we can only participate as Indians. We will not sell our heritage for a quick buck or a temporary job.”

Rather than treating First Nations in Yukon like outsiders to be haggled with, Smith proposed governments re-envision how colonial and Indigenous nations could work together under a treaty framework “that will help us and our children learn to live in a changing world.”

Smith’s overture in Ottawa would become foundational in the establishment of a rights framework in Yukon that is unique in all of Canada and recognizes First Nations as self-governing with jurisdiction over territorial lands.

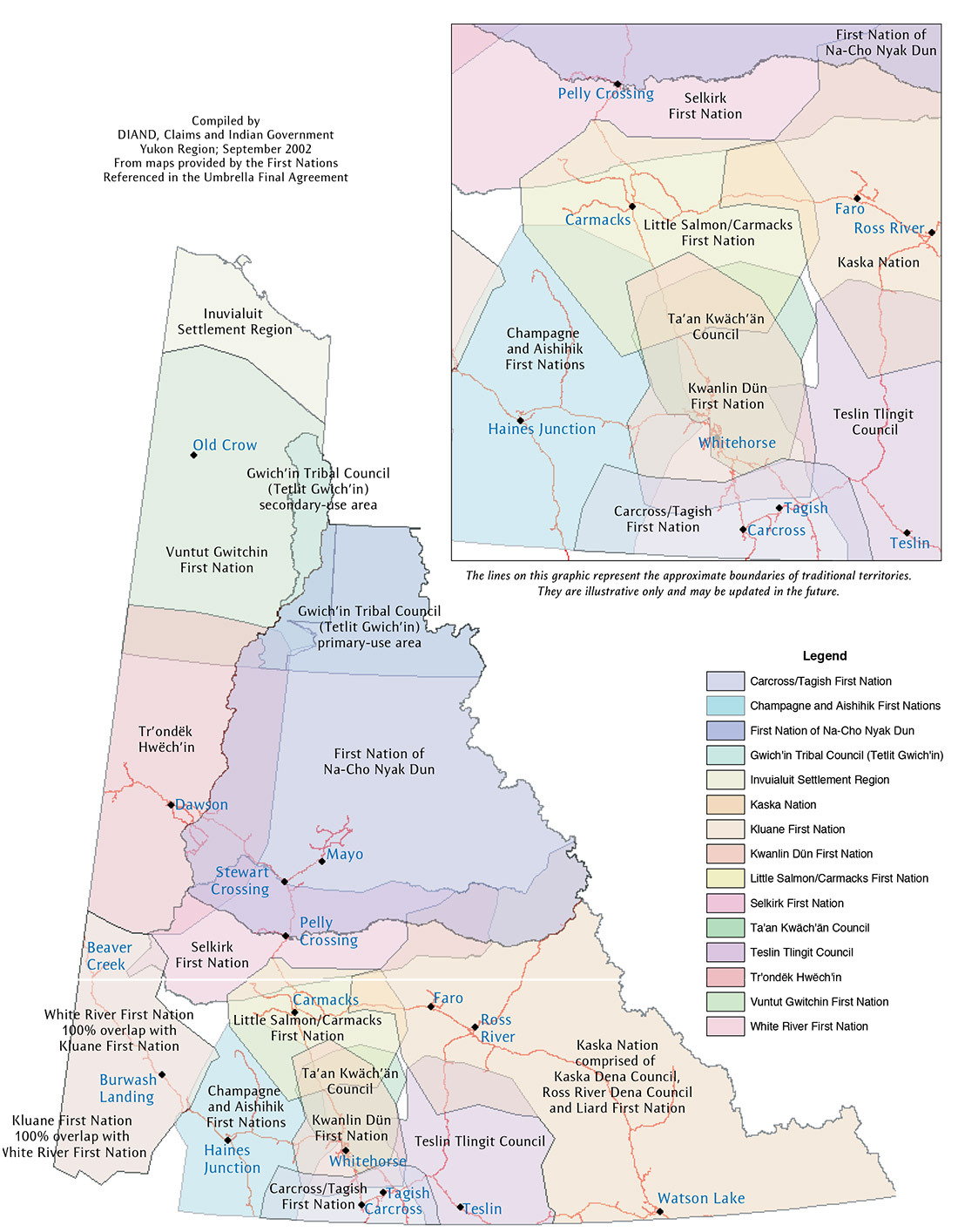

There are 14 First Nations in Yukon, 11 of which have entered into unique self-governance agreements with the territorial and federal governments. The additional three First Nations are still in negotiations.

So, how do Yukon First Nations experience Indigenous Rights and sovereignty differently than other First Nations in Canada?

Under the structure of unique modern treaties called final agreements, Yukon First Nations exercise the powers of self-governance: they manage their lands, decide what kind of development projects go where, collect taxes and create corporations.

Before final agreements were struck, Yukon First Nations were, like many other First Nations across the country, beholden to the 1876 Indian Act, which David Newhouse, director of the Chanie Wenjack School for Indigenous Studies at Trent University, describes as “one of the most visible legacies of Canada’s colonial history” designed to transform Indigenous people into democratic and “civilized” citizens.

The act was used to institute “Indian Status,” a system predicated on blood quantum, and to replace traditional forms of governance with elected band councils that were — and continue to be — directly linked to the federal government rather than Indigenous governance systems that pre-date colonization.

In order to get out from under the bind of the Indian Act, the Yukon Council of First Nations, Yukon and Canada developed a document known as the Umbrella Final Agreement, a non-binding framework designed to guide final agreements with individual First Nations, that was signed by all parties in 1993, 20 years after Smith presented his paper in Ottawa.

Tragically, Smith died in an accident in 1991, so he didn’t live to see the Umbrella Final Agreement come into force “to recognize and protect a way of life that is based on an economic and spiritual relationship between Yukon Indian People and the land.”

Elijah Smith, former chief of Champagne and Aishihik First Nation, was instrumental in the development of the rights framework that recognizes Yukon First Nations as self-governing. Photo: Champagne and Aishihik First Nation

But once the umbrella agreement was in place, individual treaties were quick to follow.

“We have our own independence,” Roberta Joseph, Chief of Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in First Nation, which signed its final agreement in 1998, told The Narwhal.

“One day we were under the auspice of Indian Affairs and the next day [we were] in charge of our own funding and lands — being able to manage those things ourselves.”

And while the final agreements set the stage for First Nations’ self-governance, the Umbrella Final Agreement paved the way for co-governance of wildlife and natural resources between Yukon and First Nations.

For instance, the agreement led to the creation of Yukon’s environmental assessment legislation and the subsequent formation of the Yukon Environmental and Socio-economic Assessment Board, which oversees project applications for industrial development projects.

Unlike in other jurisdictions in Canada, First Nations in Yukon participate as co-managers of project review boards. This isn’t the case in other provinces like British Columbia, where project reviews are conducted by provincial and federal governments and agencies and First Nations participate in processes much like other corporate or civil society actors. While Indigenous Rights are recognized and affirmed under Section 35 of the Canadian constitution and B.C. has vowed to implement the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), projects can be unilaterally imposed on First Nations and their territories (which in B.C. are predominantly untreatied and unceded) without their consent. This situation recently led to the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination calling on Canada to pause construction on the Site C dam, the TransMountain pipeline and the Coastal GasLink pipeline — three projects which are currently being built despite opposition and legal challenges from affected First Nations.

In Yukon, however, First Nations that have signed final agreements are recognized as governments in their own right and are granted decision-making authority over projects proposed in their land.

The 11 Yukon First Nations that have signed final agreements include Champagne and Aishihik First Nations, First Nation of Na-cho Nyäk Dun, Teslin Tlingit Council, Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation, Little Salmon/Carmacks First Nation, Selkirk First Nation, Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in, Ta’an Kwäch’än Council, Kluane First Nation, Kwanlin Dün First Nation and Carcross/Tagish First Nation.

The three First Nations still in negotiations are the White River First Nation, the Liard First Nation and the Ross River Dena Council.

Once a final agreement is struck, a few different things happen with First Nations territory because these modern treaties also act as comprehensive land claims.

First, the land positioned under the ownership of First Nations is called settlement land. The Umbrella Final Agreement actually placed a cap on how much of Yukon could be allotted to settlement lands:

about 41,595 square kilometres, about 8.5 per cent of the total land area. And further, the agreement actually created two categories of settlement lands that determine what kind of rights First Nations can exercise on each.

Under category A settlement lands, First Nations are the primary law-makers and decision-makers and own the rights to the land above and below the surface. In category B lands, First Nations own the rights above the surface, but not below, so this greatly impacts how decisions are made about oil and gas and mining projects.

The umbrella agreement further stipulates that category A lands in Yukon cannot exceed 25,899 kilometres and category B lands cannot exceed 15,695 kilometres.

What proportion of the allowable kilometres goes to each First Nation is something negotiated within each nation’s final agreement.

First Nations, such as the self-governing Vuntut Gwitch’in, work with the Yukon government to co-manage lands that are still held by the Crown. These co-management relationships give First Nations in Yukon more control over lands and resources than in many other parts of Canada. Photo: Matt Jacques / The Narwhal

But almost the entire Yukon landmass falls within First Nations traditional territories, so what happens to those landscapes? Technically, Yukon First Nations don’t own their traditional territories, but are given a high level of involvement in what happens on those lands (they’re considered “special management areas”) as they’re managed under the authority of the Yukon government. First Nations also exercise their constitutionally protected Indigenous Rights on their traditional territories to hunt, trap, fish, protect cultural artifacts and even co-manage parks.

Traditional territory that falls outside of settlement land classification can also fall into a category of fee simple settlement land, which grants a First Nation similar rights to any Yukoners who has purchased a parcel of land.

Kris Statnyk, a Vancouver-based lawyer and citizen of self-governing Vuntut Gwitch’in First Nation in Old Crow, Yukon, said because settlement land represents a relatively small portion of a Yukon First Nations’ traditional territory, First Nations have had to work in creative and evolving ways with the Yukon government to co-manage lands held under Crown title.

That co-management, particularly of natural resources, has led to the creation of new institutional relationships that foster participation from Yukon First Nations, Statnyk said.

“That, I think, has been really unparalleled elsewhere.”

One particular way these creative relationships have unfolded is through the Yukon Land Use Planning Council, a joint body consisting of members from the federal and Yukon governments and the Council of Yukon First Nations that recommends policies and priorities to affected First Nations and the Yukon government on land use planning. The council also suggests terms of reference for regional land use plans, which are carried out by independent commissions.

The famed Peel watershed in Yukon was the subject of a decade-long land use planning process, which resulted in the vast majority of the landscape being protected from roads and industrial development. Photo: Peter Mather

Now, land use plans are a thing in Yukon. And a part of the reason why they’re pursued with such passion goes back to the Umbrella Final Agreement and even Smith’s position paper.

The paper notes “the cornerstone of the settlement is land. This means that the Indian people will own land and have financial resources to develop that land for the benefit of the people living on that land.”

So when the Umbrella Final Agreement was cast, it placed an emphasis on the need for regional land use plans that would set out in advance what should and should not occur on specific landscapes.

Perhaps Yukon’s most famous land use plan was developed for the Peel Watershed, a 68,000 square-kilometre stretch of largely undeveloped mountains, wetlands, rivers, tundra and forest. It is world-renowned for its rugged natural beauty, ecological richness — and mining potential.

The Peel Watershed’s land use plan took more than a decade to complete, owing in part to a legal battle that wound its way up to the Supreme Court of Canada, where parties battled over just how much industrial development should be allowed in the region and under the provisions set out in the Umbrella Final Agreement. The courts ultimately sided with Yukon First Nations and conservation organizations and now mining, roads and oil and gas projects are only permitted in one parcel that represents about 17 per cent of the land mass.

Read more: What Does The Peel Watershed Ruling Mean for the Yukon – and Canada?

There are 10 land use planning regions in Yukon and plans have so far only been completed for two regions: North Yukon and the Peel. The Dawson land use planning process is currently underway and highlights how significant and potentially controversial these planning processes can be, especially when they have the potential to set conservation and First Nations priorities against industry and commercial interests.

The Dawson region falls within the territory of the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in First Nation and Chief Joseph has expressed dismay that it has taken so long to develop a land use plan while placer mining operations forge ahead, causing potentially irreversible damage to waterways and wetlands.

Despite the controversy over the Dawson land-use plan, Joseph said the establishment of final agreements has granted First Nations greater decision-making authority when it comes to land use plans.

The Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in First Nation final agreement “has really provided us with all of the tools and instruments that we needed to manage ourselves like our ancestors did over a hundred years ago and how they took care of the land,” Joseph said. “It was a way to also regain our culture and traditions back and a way to preserve that history.”

Statnyk said the agreements have forced all parties to engage with the question of Indigenous self-governance “that hadn’t been addressed in the enactment of section 35 and the constitutional conferences that followed.”

Implementation hasn’t always been smooth, especially when governance issues really come down to who has the ultimate say over land.

“We’re that weird group of 11 Yukon First Nations that each have their own distinct arrangement,” Statnyk said. “That continues to be an uphill battle, you know, still being treated like Indian Act bands, essentially, this sort of colonial hangover.”

“It’s hard to break those patterns. We’re trying to implement self-government when colonization is still ongoing, quite simply.”

Changing perspectives on Indigenous Rights and Title may signal a need for evolution when it comes to the way First Nations rights are handled in Yukon. One Yukon First Nation in the treaty negotiation phase has pointed out that the Umbrella Final Agreement no longer functions smoothly in the new era of reconciliation.

The Liard First Nation, which very recently announced its intention to seek self-governance, wants to enter into a modern treaty outside the precepts of the Umbrella Final Agreement.

Chief Stephen Charlie told Yukon News he views the Umbrella Final Agreement as too outdated to functionally guide new treaties and land claims.

“That document is over 35 years old, and a lot has changed in Aboriginal Rights in title and recognition in this country,” he said. Charlie noted restrictions on the amount of traditional territory and mineral resources that can be owned by a Yukon First Nation is a major hurdle for his nation.

“Our Elders were so wise, they realized that the [Umbrella Final Agreement] was a dead end for us. We are rich in resources in our traditional territory, and what they were offering is just miniscule [compared] to what we could move forward on,” he said.

Map of Yukon First Nations traditional territory. Photo: Government of Canada

The Liard First Nation’s discontent with the Umbrella Final Agreement could signal the need for modernization, even though the modern treaties developed by Yukon First Nations were trailblazing and remain cutting-edge, said John Borrows, Canada research chair in Indigenous law at the University of Victoria.

Yukon’s final agreements represent “part of a family of possibilities,” he said, pointing to the development of more recent modern treaties like the Nisga’a Treaty, negotiated between the Nisga’a First Nation, B.C. and the federal government in 2000. Under this treaty, the first of its kind in B.C., the Nisga’a government has the authority to enact laws, manage its lands, set environmental protections and administer social services. But the Nisga’a government still falls under the authority of both the Canadian Constitution and the Charter of Canadian Rights and Freedoms.

In an interesting twist, the Nisga’a Treaty is based on a ‘meet or beat’ principle that grants authority to the government with the highest standards for laws pertaining to child protections, education and forestry. So if the Nisga’a laws meet or exceed provincial standards for the management of forests, those laws will take priority.

These creative arrangements have come a long way from the first modern treaty signed in Quebec 1975, Borrows said.

While that treaty long-preceded the Yukon First Nations final agreements, Borrows said First Nations are “renovating” earlier agreements, “renegotiating dimensions” of what earlier agreements could mean for their communities.

“I think a lot of self-government has not only been recognized but also exercised through those agreements, and they seem to keep getting better all the time.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. Angello Johnson’s shoulders burn, and his arms...

Continue reading

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...

We’re excited to share that an investigation by The Narwhal is a finalist for the...

A new documentary, Nechako: It Will Be a Big River Again, dives into how two...