Ontario’s public service heads back to the office, meaning more traffic and emissions

For 15 years and counting, my commute from Mississauga to Toronto has been mired by...

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter.

The town of St. Paul, Alta., is the kind of place where you can buy a basket of homemade preserves and local beef jerky from the Chamber of Commerce on Main Street. It’s a farming community at heart, surrounded by fields and gently rolling hills. It’s not huge, just under 6,000 people, and the biggest tourist attraction is the world’s first UFO landing pad, which attracts “an average of 20 people per day,” according to the local newspaper.

“It’s not the centre of the universe,” Amil Shapka says with a smile. He’s a retired dentist who describes himself as being “born here, raised here, went to school here, left for the big city, hated it, came back and lived happily ever after.”

Shapka lives not far from town down a gravel road. It’s “me and the bears and the squirrels,” he says. “Being Ukrainian, there’s a bit of the thousands of generations of farmers in me. Our connection — my connection — to the land is part of my well being.”

But against this backdrop, change is afloat.

If everything goes according to plan, the town will soon be part of one of the world’s largest carbon capture and storage networks. A $16.5-billion megaproject — much of which could be taxpayer money — is in the works from Pathways Alliance, a group of the six largest oilsands companies. Advocates say carbon capture is a high-tech antidote to the global climate crisis and a solution to reduce heat-trapping emissions created by producing and burning fossil fuels. Critics say it is untested, expensive and not feasible at scale.

Here in northeastern Alberta, Pathways Alliance seeks a proving ground.

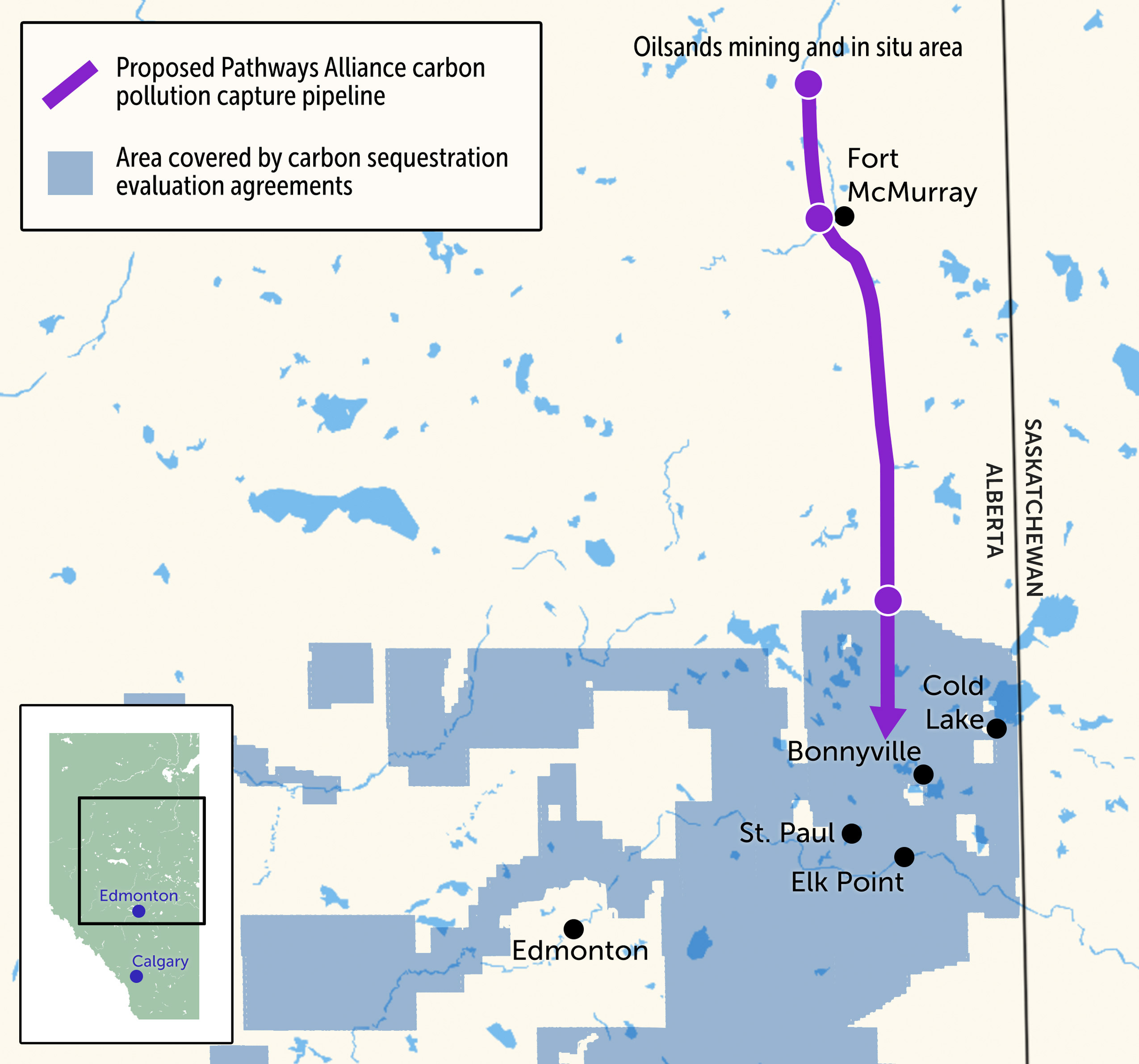

The consortium is planning to build a 400-kilometre pipeline as wide as 36 inches (a little under a metre) to carry carbon pollution from the oilsands. Liquid carbon dioxide will be buried deep under the Earth’s surface, injected into the sandstone that lies more than a kilometre underground. Huge swaths of the province — thousands of square kilometres — are part of what are called evaluation agreements — contracts with the Alberta government that grant a company the right to conduct testing, including drilling wells and injecting substances deep underground, to find good places to store carbon pollution.

Canadian Natural Resources Limited, a Pathways member, has an evaluation agreement that blankets St. Paul and the surrounding region. Pathways Alliance filed an application for the pipeline to the Alberta Energy Regulator in March — the first step in the approval process.

This worries some local residents, who are concerned groundwater is at risk and that an explosion or a leak could mean asphyxiation caused by odourless, invisible carbon dioxide. They wonder who will respond in the event of an emergency — will it be the local volunteer fire department? Will leaking carbon dioxide interfere with the oxygen-dependent engines of emergency vehicles? Some First Nations are concerned about implications for Treaty Rights and the ability to hunt, trap or fish. Athabasca Chipewyan Chief Allan Adam has asked the provincial regulator to require an environmental assessment of the project “to ensure the rights of [Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation] are protected.”

For others, a new pipeline is good news for the economy and could bring good jobs to the region. Will the project pit neighbour against neighbour? And, crucially, many wonder, will it even work?

“This isn’t really even proven technology. They’re going to roll the dice using billions of public dollars and potentially put our future, property values and access to water at risk,” Shapka says. “Does this serve the public interest?”

Penny Fox grew up in Ontario, married a “farm boy” and moved to Alberta in 1987. “If we were millionaires, we’d be farming,” she says with a laugh. As it is, they both have other careers — her in small business development, him in government — and live on a small farm just south of St. Paul where in their free time they sell hay, work in the vegetable garden and add to their sizeable collection of firewood.

Fox has lived in various parts of Alberta and is familiar with the impacts of oil and gas development. After all, the province already has more than 400,000 kilometres of pipelines criss-crossing under the surface. “We all depend on it,” she says, acknowledging the economic impact of the industry in Alberta and across Canada.

But when she heard a carbon dioxide pipeline was planned across the road from her house, she had a lot of questions. This, she says, doesn’t feel the same as an oil or natural gas pipeline. Although those also come with risks, they have what she views as a reasonable framework for regulation.

“This is something totally different,” Fox says. She’s a member of a grassroots group that formed, as “farmer called farmer, neighbour called neighbour” when representatives of the project — called land agents — started knocking on doors in the region.

It started with Shapka, who sprung into action when he heard about the land agent seeking access to a neighbour’s property in exchange for a cheque. He rented the local community hall and started making phone calls.

Fox, Shapka and other community members call themselves the “No to CO2” group. Part of their mission, Fox says, is to get access to the project details — information is scarce, especially since Pathways Alliance scrubbed its website in response to new federal greenwashing regulations — and to understand the risks of the project to the people who live nearby. The alliance did not respond to The Narwhal’s multiple requests for an interview, nor to a list of detailed questions about the project.

“What we were trying to do is not tell people what to do, but give them enough information for them to understand what it means,” Fox says. “We need to ask questions so that we can clearly understand what this is.”

“What happens if the North Saskatchewan gets polluted?” she asks, referring to the major river that flows just north of the community and on to Saskatchewan. “How many communities — how many people — rely on that for a water source? Because, I mean, it’s not just Alberta. It’s not just an Alberta problem.”

“They should be able to answer those questions.”

Some people in St. Paul are excited about the potential benefits of the project — they see it as a major investment in Alberta’s future. Bernie Poitras is one of them. He was a rodeo announcer who worked in the oilpatch before he became the District 12 commander of the Otipemisiwak Métis Government, formerly the Metis Nation of Alberta, last fall.

Poitras’ family has been in the area ever since his great-grandfather came to Alberta in 1874 from Manitoba. He still finds time to be an announcer at local hockey games, but much of Poitras’ time is now taken up with politics — and that means talking about the carbon pipeline Pathways wants to build through the region. “It is very complicated,” he says over coffee at the local A&W.

“It’s going to employ a lot, a lot, of people,” Poitras says. Many in the community look forward to either joining construction crews themselves, or earning the money the workers spend on restaurants, hotels and other services.

In a briefing report submitted to a House Committee focused on the environment, Pathways said its project would create “15,000 to 20,000 high-paying jobs during construction, with approximately 1,000 permanent jobs post-construction,” adding it would “stimulate the provincial and national economy.”

Not only that: some see it as an opportunity to be part of a solution to global warming. International organizations like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and the International Energy Agency say carbon storage is part of a viable path to net-zero emissions — and needs to be expanded rapidly to have an impact.

Poitras was recently at the Lloydminster Heavy Oil Show, where Pathways Alliance sponsored a fireside chat. There, after talking to people in the industry, he was reassured about the technology. “I don’t really think it’s gonna affect the groundwater,” he says. “It’s not an oil line, it’s a carbon capture line, and it’s going deep underground.”

Not everyone is so sure. Fox, Shapka and others are concerned about myriad other potential risks. Sure, the worst might not happen. But, they wonder, what happens if it does?

When carbon pollution is injected deep underground there are two options: one, it can be used for what’s known as “enhanced oil recovery” — in essence, injecting carbon dioxide into a well so you can get at more oil. A 2022 report found nearly three-quarters of captured carbon pollution around the world is used to extract more oil which, as critics point out, leads to more profit and more carbon pollution. There are more than 8,000 kilometres of carbon dioxide pipelines in the United States, “virtually all” of which are used for enhanced oil recovery, according to the U.S. Congressional Budget Office, which says of 15 carbon capture storage projects in the country as of December 2023, 13 are for enhanced oil recovery.

The second option is for carbon pollution to be “permanently stored” deep underground.

“This is waste disposal,” Shapka says. “This is an industrial byproduct and calling it storage, I think, minimizes what it really is. That stuff’s going to be pumped down there in perpetuity.”

That raises questions, among which concerns for groundwater are prominent. “Water is number one,” Shapka says.

He’s not alone in his concerns. In Australia, the Queensland government recently announced it would prevent the storage of carbon pollution under a 1,700,000-square-kilometre area of the state. Farmers had pushed for the ban, noting an environmental assessment found carbon storage would “likely cause an irreversible or long-term change in water quality” if carbon pollution were to migrate through the region’s aquifer, spreading contaminants such as lead and arsenic.

The Alberta Energy Regulator, which is responsible for evaluating the Pathways Alliance application, said ensuring carbon dioxide doesn’t migrate into groundwater is a “critical focus area” and that it requires companies “to review the area geology to ensure a high level of confidence” to ensure that. It also requires a hazard and risk assessment be conducted and that all risks are “fully mitigated” before the project will be approved.

“All carbon dioxide storage projects require a monitoring, measurement and verification plan, to outline how the company will ensure the pollution stays put, and what “remedial actions [will] be taken if anything does go wrong.”

But the possibility something will go wrong remains, which is why several groups are asking for an environmental assessment. In response to emailed questions from The Narwhal, a spokesperson for the Alberta Energy Regulator noted the project does not automatically trigger a provincial environmental assessment (like, say, an oilsands mine or a large hydro dam). If the regulator decides an assessment is not needed, the spokesperson said, the risks associated with the project will be evaluated under the standard application process.

The spokesperson for the regulator said leaks of carbon dioxide from a pipeline “may briefly” turn surface water into ice “but it would not impact groundwater.” According to the regulator, carbon dioxide doesn’t present risks for groundwater when it’s in a pipeline and the risks exist only when it’s buried deep underground.

A Pathways Alliance land agent told Fox there would be test wells around injection sites — the spots where carbon pollution is buried — to check for leaks or changes to the water, but that doesn’t reassure everyone.

Several First Nations in the region, including Heart Lake First Nation, Beaver Lake Cree Nation, Whitefish Lake First Nation, Kehewin Cree Nation, Frog Lake First Nation, Cold Lake First Nations and Onion Lake Cree Nation, have also been asking questions about the project. Some have expressed concern about their abilities to exercise their Treaty Rights. (None of these nations responded to requests for an interview.)

“We don’t know how pumping carbon underground will affect our lakes, our rivers — even our underground reservoirs,” Michael Lameman, a councillor at Beaver Lake Cree Nation, told CBC earlier this year. (Lameman did not respond to a request for an interview.)

Pathways Alliance has provided a high-level map of the proposed project, but not enough information about specifics, according to Moronkeji (Kg) Banjoko, government relations and consultation coordinator with the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation’s Department of Dene Lands and Resource Management. “There is no information about what the project will do — as a whole and cumulatively with other industrial development in the area — to the environment, local communities and [Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation’s] Treaty Rights,” Banjoko wrote in an email to The Narwhal.

The nation has a number of concerns, Banjoko said, including “the addition of another pipeline to the landscape which will cross the Athabasca River in multiple places as well as other watercourses, cause construction impacts, destroy animal habitat and create easier sightlines for hunters and predators to hunt caribou and moose.” Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation would like Pathways Alliance to support an Indigenous-led assessment of the project — or, failing that, to request a joint provincial-federal environmental impact assessment.

Carbon capture and storage “allows [Pathways] to talk a big game about action on climate change before they have committed any serious resources to building the project and reducing emissions — all while continuing to produce record amounts of oil,” Banjoko added.

Ever-present concerns about a leak, or worse, an explosion, aren’t unfounded.

In 2020, a 24-inch (0.6-metre) carbon dioxide pipeline in Mississippi — in the tiny town of Satartia, population 50 — ruptured after a mudslide. More than 31,000 barrels — nearly 5,000,000 litres — of carbon dioxide were released. Within minutes, there were reports of people having seizures or falling unconscious. The carbon dioxide “immediately began to vaporize,” according to a federal Department of Transportation investigation, and spread across the county.

At least 45 people were hospitalized and hundreds were evacuated. “It looked like you were going through the zombie apocalypse,” the county’s emergency director told NPR in 2023, adding that people were laying on the ground, shaking and unable to breathe. The company behind the pipeline took two hours to tell the relevant authorities about the explosion (it has since paid nearly US$3 million in fines). Some residents said they spent more than an hour unconscious in a vehicle filled with carbon dioxide and had to have supplemental oxygen for months after the incident.

In April of this year, another carbon dioxide pipeline ruptured in Louisiana. In September, carbon dioxide leaked from an injection well in Illinois.

Carbon dioxide pipelines are not new — they crisscross North America, mostly for enhanced oil recovery. In the last 10 years, according to an analysis from the Great Plains Institute, there have been 63 instances of leaks or accidents. Since 1994, carbon dioxide pipeline accidents have released approximately 135,000 barrels — which amounts to more than 21 million litres — in the United States.

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, “there is no indication that problems for carbon dioxide pipelines are any more challenging than those set by hydrocarbon pipelines.” That said, they may be more subject to what are known as “longitudinal running fractures” — a rapid and catastrophic unzipping, or splitting, of a pipeline — than other gas pipelines and need adequate safety features in place.

This leads to many questions, including about emergency response vehicles, which have combustion engines that need oxygen to run, and can fail when heavier carbon dioxide displaces it.

“I don’t know what’s going on,” NPR reported a 911 caller said when the Satartia explosion happened. “My car stopped, it won’t move.”

That pipeline was just over 1.5 kilometres from the small Mississippi town. In St. Paul, it is not yet exactly clear where the pipeline could run, but early plans suggest it could be a little more than a kilometre from the eastern edge of town. A spokesperson for the Alberta Energy Regulator said by email that any carbon dioxide pipeline licensed by the regulator is required to have a corporate emergency response plan.

“I don’t want to be next to that thing if that pipeline ruptures,” Shapka says, pulling apart a fresh apple muffin. “My roots are here, and everything familiar is here. But I’d really have to question that.”

The potential impacts of the Pathways Alliance carbon pipeline and storage plan are being talked about at kitchen tables along the proposed route. Meanwhile, its potential benefits are being touted around the world, including at the annual United Nations meeting about climate change.

The problem is real: there is just too much pollution. Nearly 50,000 megatonnes of carbon pollution are emitted globally each year. Around the world, “human activities have raised the atmosphere’s carbon dioxide content by 50 per cent in less than 200 years,” according to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA).

In Canada, 677 megatonnes were emitted in 2021. Two weeks ago, the federal government announced plans to introduce draft legislation to cap emissions from the oil and gas industry, something industry leaders oppose. Instead, they and other proponents say capture and storage projects are crucial to reducing carbon pollution and mitigating climate change in the immediate future.

The Pathways Alliance plan for the $16-billion project aims to bury 10 to 12 megatonnes of carbon dioxide deep underground each year. That’s approximately one-eighth of reported carbon pollution from the Alberta oilsands annually, or roughly equivalent to the carbon pollution emitted by the oilsands every six weeks.

Pathways, whose six members control 95 per cent of oilsands production, says it wants to “produce some of the cleanest barrels of oil in the world” and to be net zero by 2050. Carbon capture, it says, is “safe, proven and reliable.”

But that promise comes with caveats, especially if you ask David Schlissel at the U.S.-based Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. He’s been following carbon capture closely since 2007 and is concerned that the endeavour is more “hype” than evidence — not to mention the price tag.

“There’s no evidence that it will capture 90 to 95 per cent of the carbon dioxide it’s designed to capture,” Schlissel says, noting data shows real-world carbon capture rates range from 10 to 78 per cent. When the whole life cycle of carbon capture efforts, which also release carbon pollution, are taken into account, he says, “it’s unlikely to have a major dent in greenhouse gas emissions.”

Carbon capture is an attempt at gaining “social licence” for continued production of fossil fuels, according to the U. S. House of Representatives’ central investigative committee, which is among critics saying the promise of a tech fix relieves pressure to pivot to energy sources that produce less carbon pollution. Global oil production is at record levels in 2024, according to the International Energy Agency, and 2023 was a banner year for oilsands profits.

Both the federal government and the Alberta government have proven eager to financially support the oil industry’s carbon capture plans.

Carbon capture is “a tool in the toolbox” of reducing carbon pollution, according to Matt Dreis, a senior analyst with the Pembina Institute’s oil and gas program.

“Carbon capture and storage is going to be a big part of emissions reductions in Alberta,” Dreis says. “It’s one of the largest opportunities to reduce emissions from [the Alberta oilsands] sector specifically.”

But critics have balked at the cost — and the amount that could be subsidized by taxpayers. Behind the scenes, Pathways Alliance has been lobbying for tax breaks and incentives from governments, including an “assurance” from the federal government that no part of the project would require a federal review under the beleaguered Impact Assessment Act.

The potential liability for Canadians doesn’t stop there. In Alberta, the government assumes liability for a carbon capture project after it is officially certified as complete: it asks companies to pay into a “stewardship fund” to cover or offset costs, but otherwise maintenance, monitoring and leaks are the government’s responsibility. In other provinces, like Manitoba, companies will retain responsibility for costs related to leaks or repair.

“Make them financially responsible,” Schlissel says of future risks of leaks. “Let them put their money where their mouth is.”

Schlissel, who is 77, is curious if his doubts will be proven wrong. “I’ve asked one of my younger colleagues [to] do a seance in 30 years and let me know how it comes out,” he says with a rueful laugh.

At her home just south of St. Paul, where she has lived with her husband for the past 14 years, Fox surveys her garden and its late season bounty — tomatoes, pumpkins and some corn that survived a recent bear visit. She gestures across the road, where the pipeline is set to be.

Right now, it’s just a field.

“They were in Dubai, they were in Calgary and Texas and they’re all over the world,” she says of the places Pathways Alliance representatives have publicly extolled the virtues of their carbon capture plan. But, she says, “They’ve spent about three hours here.”

That leaves many in the community feeling neglected — and undervalued. Is their farming community something of a guinea pig? If something goes wrong, are they a sacrifice zone for a solution to a much bigger problem?

Fox is well aware of the global conversation about carbon pollution and the high stakes for the planet — as well as for fossil fuel companies. “They’re being forced into coming up with a solution around carbon dioxide,” she says. “We’re just not convinced this is it.”

“I’m just not convinced all of this money and all this work is going to make a tinker’s damn of a difference.”

Enbridge Gas will face Waterloo Region in a hearing before the Ontario Energy Board to renew an agreement that would allow the company to continue...

Continue reading

For 15 years and counting, my commute from Mississauga to Toronto has been mired by...

For our last weekly newsletter of the year, we wanted to share some highlights from...

The fossil fuel giant says its agreement to build pipelines without paying for the right...