Ontario’s public service heads back to the office, meaning more traffic and emissions

For 15 years and counting, my commute from Mississauga to Toronto has been mired by...

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter.

Around the world, governments, researchers and companies are scrambling to reduce the sheer volume of carbon pollution created by modern life. Among the ideas gaining traction in Canada is carbon capture — collecting carbon dioxide before it is sent up into the atmosphere.

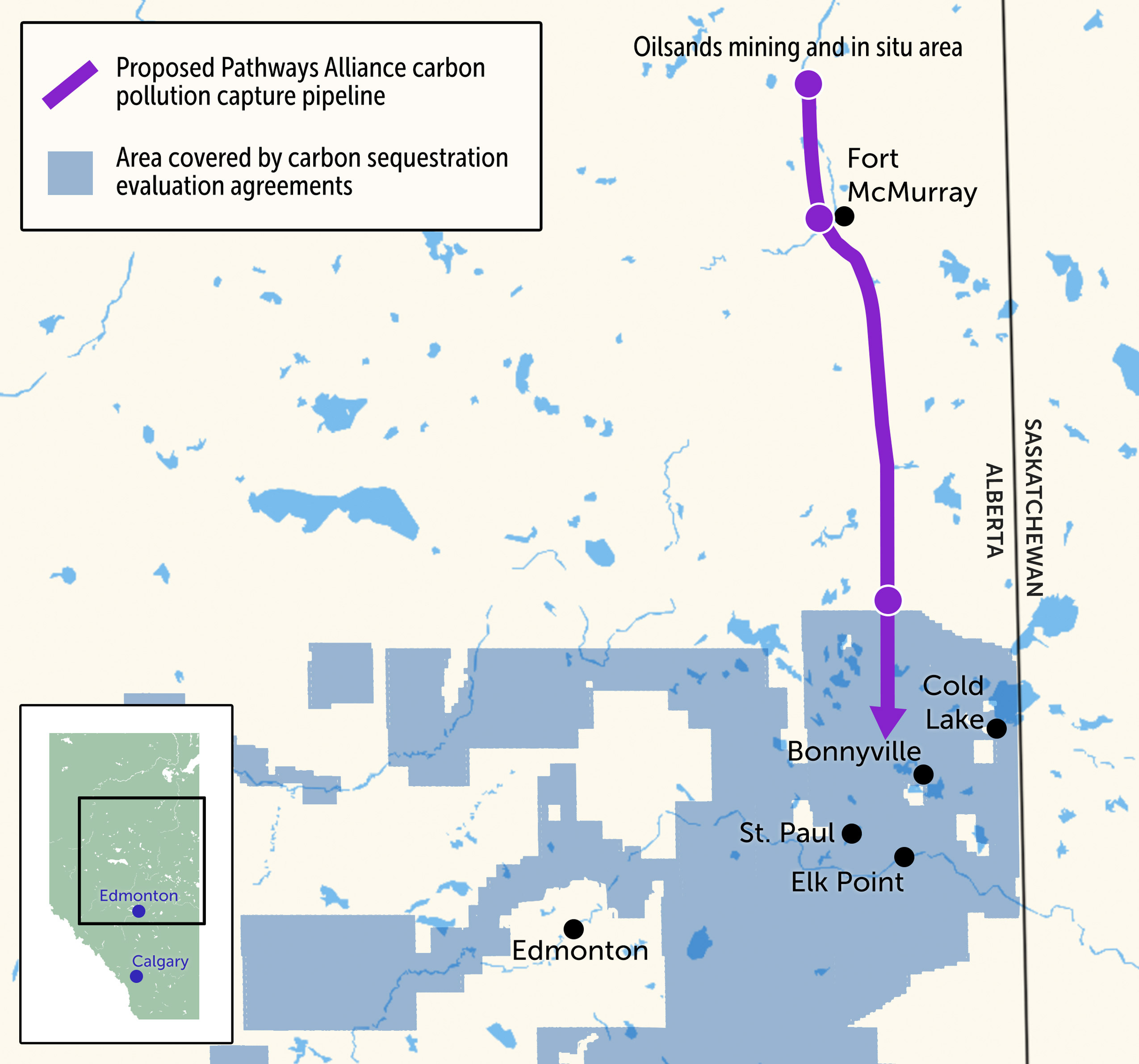

The Pathways Alliance group of oil giants want to do just that, collecting carbon pollution from the Alberta oilsands and shipping it approximately 400 kilometres by pipeline to an underground storage site just outside St. Paul, Alta., where it will be injected deep underground — forever.

Though the plan is anything but final, Pathways, whose six members control 95 per cent of oilsands production, did put in its first application for regulatory approval earlier this year and has said it has invested heavily in its plans.

But the proposal doesn’t sit well with everyone along the pipeline route and the Alberta Energy Regulator recently confirmed the province will not be requiring the project undergo an environmental assessment.

Here’s what you need to know about some very tangible risks Albertans on the ground are talking about as a carbon pipeline might move in next door.

Carbon dioxide pipelines are not new — they crisscross North America (mostly for use in extracting more oil from the ground, rather than permanent storage).

Any major project comes with risks. In 2020, a carbon dioxide pipeline ruptured in Mississippi, showing just how serious those risks can be. Within minutes, there were reports of people having seizures or falling unconscious. At least 45 people were hospitalized. The county’s emergency director likened it to “the zombie apocalypse.”

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, “there is no indication that problems for carbon dioxide pipelines are any more challenging than those set by hydrocarbon pipelines.” That said, they may be more subject to what are known as “longitudinal running fractures” — a rapid and catastrophic unzipping, or splitting, of a pipeline — than other gas pipelines.

This leads to many questions for Albertans near the proposed Pathways Alliance carbon pipeline route, including about emergency response vehicles, which have oxygen-dependent engines that can fail if carbon dioxide leaks.

A spokesperson for the Alberta Energy Regulator, which is responsible for evaluating the Pathways Alliance application, said by email that any carbon dioxide pipeline licensed by the regulator is required to have a corporate emergency response plan.

Albertans alongside the proposed path of the carbon pollution pipeline worry about how a potential leak could impact groundwater, citing similar concerns across the globe.

In Australia, the Queensland government announced it would prevent the storage of carbon pollution under a 1.7-million-square-kilometre area of the state. An environmental assessment found carbon storage would “likely cause an irreversible or long-term change in water quality” if carbon pollution were to migrate through the region’s aquifer, spreading contaminants such as lead and arsenic.

The Alberta Energy Regulator said ensuring carbon dioxide doesn’t migrate into groundwater is a “critical focus area” and that it requires companies “to review the area geology to ensure a high level of confidence.”

Several First Nations in the region, including Heart Lake First Nation, Beaver Lake Cree Nation, Whitefish Lake First Nation, Kehewin Cree Nation, Frog Lake First Nation, Cold Lake First Nations and Onion Lake Cree Nation, have been asking questions about the project. Some have expressed concern about their abilities to exercise their Treaty Rights.

“We don’t know how pumping carbon underground will affect our lakes, our rivers — even our underground reservoirs,” Michael Lameman, a councillor at Beaver Lake Cree Nation, told CBC earlier this year.

Pathways Alliance has not provided enough information about specifics, according to Moronkeji (Kg) Banjoko, who works in the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation’s Department of Dene Lands and Resource Management.

“There is no information about what the project will do — as a whole and cumulatively with other industrial development in the area — to the environment, local communities and [Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation’s] Treaty Rights,” Banjoko wrote in an email.

Nearly 50,000 megatonnes of carbon pollution are emitted globally each year. The Pathways Alliance plan for the $16-billion project aims to bury 10 to 12 megatonnes of carbon dioxide deep underground each year — roughly equivalent to the carbon pollution emitted by the oilsands every six weeks.

Pathways says it wants to “produce some of the cleanest barrels of oil in the world” and that carbon capture is “safe, proven and reliable.”

But experts like David Schlissel at the U.S.-based Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis are concerned carbon capture is more “hype” than evidence.

“There’s no evidence that it will capture 90 to 95 per cent of the carbon dioxide it’s designed to capture,” Schlissel says, referring to an oft-cited industry standard for carbon capture rates — a baseline target that acknowledges the amount of carbon pollution that needs to be be captured to be worth the investment. Schlissel notes data shows real-world carbon capture rates range from 10 to 78 per cent.

Others say the technology is an attempt at gaining “social licence” for continued production of fossil fuels — the U. S. House of Representatives’ central investigative committee is one such critic, saying the promise of a tech fix relieves pressure to pivot to energy sources that produce less carbon pollution.

“They were in Dubai, they were in Calgary and Texas and they’re all over the world,” one Alberta landowner says of the places Pathways Alliance representatives have publicly extolled the virtues of their carbon capture plan. But, she says, “They’ve spent about three hours here.”

Some residents along the proposed pipeline route feel shut out of the process, noting that landowners whose properties are directly affected might have a say, but the rest of the community does not.

More than anything, they say, they want Pathways Alliance to answer their questions about the risks. (Pathways Alliance did not respond to multiple requests for an interview, nor a detailed list of questions about the project.)

Enbridge Gas will face Waterloo Region in a hearing before the Ontario Energy Board to renew an agreement that would allow the company to continue...

Continue reading

For 15 years and counting, my commute from Mississauga to Toronto has been mired by...

For our last weekly newsletter of the year, we wanted to share some highlights from...

The fossil fuel giant says its agreement to build pipelines without paying for the right...