Ontario’s public service heads back to the office, meaning more traffic and emissions

For 15 years and counting, my commute from Mississauga to Toronto has been mired by...

As the state of Montana moves to set more stringent selenium limits for a cross-border body of water, environmental groups are concerned British Columbia is stalling similar efforts aimed at reducing pollution from coal mines in the province’s southeast.

B.C. and Montana have been working to develop a new limit for selenium pollution in the Lake Koocanusa watershed since 2015.

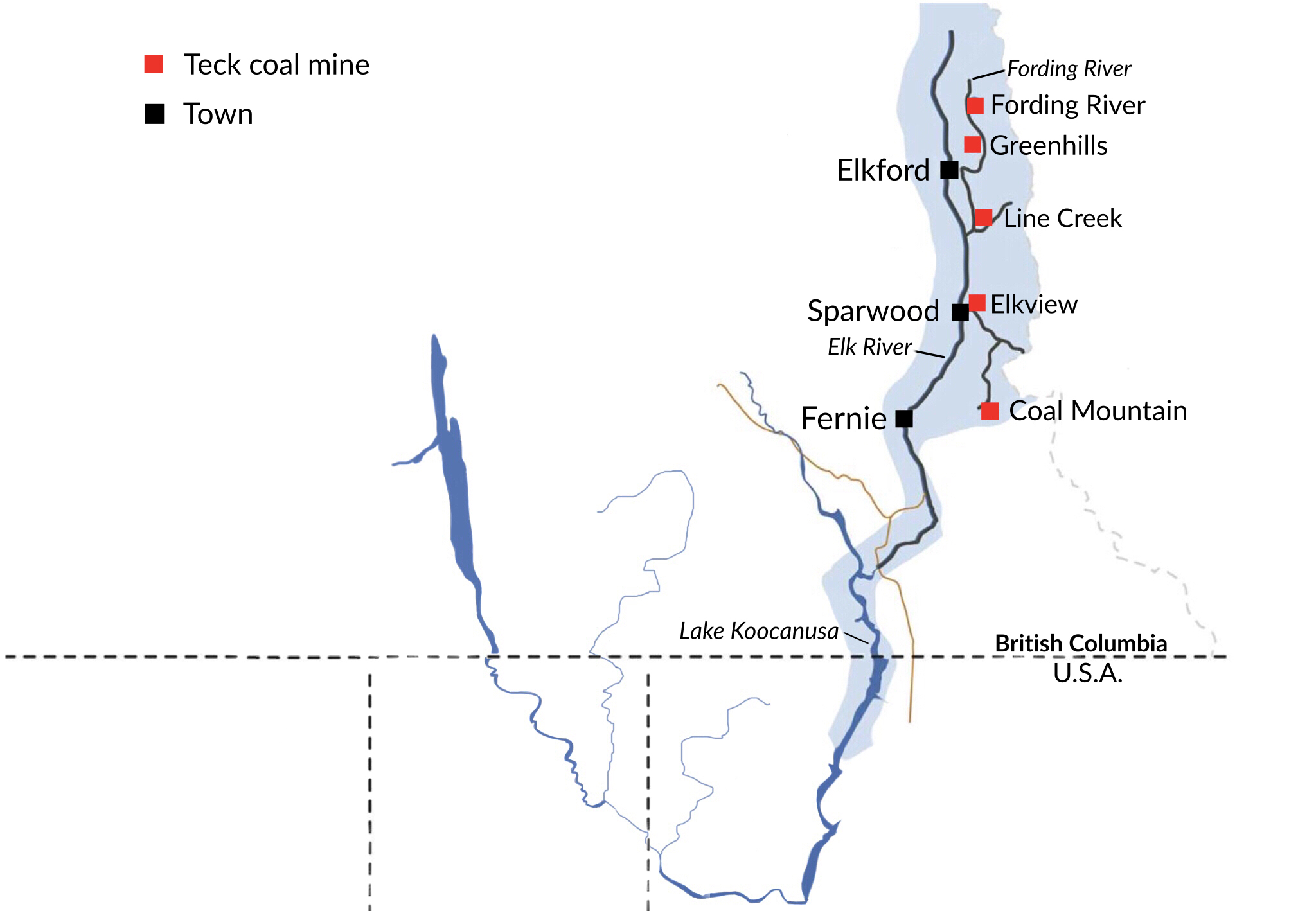

Ninety-five per cent of the selenium entering Lake Koocanusa, a reservoir that spans the B.C.-Montana border, comes from the Elk River, according to a September 2020 presentation from Montana’s Department of Environmental Quality.

The element leaches into the waterways from piles of waste rock at coal mines operated by Teck Resources in the Elk Valley, and with a number of proposed mines undergoing environmental assessments there are concerns the problem could get worse.

“If we have a [selenium] limit going into those assessments then it’s going to be really clear to everyone and we can make decisions based on those limits,” said Lars Sander-Green, mining lead with Wildsight, a conservation group based in the Kootenays.

“We really want to … get this limit adopted soon so that we can have some certainty,” he said.

Montana’s Department of Environmental Quality announced on Sept. 24 that it had begun the process to establish a proposed site-specific selenium limit for the water column in Lake Koocanusa of 0.8 parts per billion.

“The goal for both Montana and British Columbia is to adopt aligned standards that protect aquatic life,” the department’s press release noted.

B.C.’s existing water quality guidelines recommend selenium levels be kept to two parts per billion to protect aquatic life. In waters tested throughout the Elk Valley, however, selenium levels have been found to exceed 150 parts per billion near mining activities. In the last year, Teck reported major population declines of westslope cutthroat trout in three waterways downstream of the company’s Elk Valley coal mines.

Average selenium levels in Lake Koocanusa, which straddles the Canada-U.S. border about 100 kilometres south of the Elk Valley mines, are currently about one part per billion, according to the Montana Department of Environmental Quality’s presentation.

Teck’s metallurgical coal mines are all upstream of the transboundary Koocanusa Reservoir. Map: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

In late September, B.C.’s Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy released a statement saying the province had not yet selected its own proposed water-quality objective for selenium in Lake Koocanusa.

“B.C. is committed to a science-based process informed by the best available data,” the statement said.

“A selenium-level target will only be established once B.C. is fully confident that the process has met this high standard and after seeking consensus with the Ktunaxa Nation Council on a recommended standard for selenium for this transboundary waterbody,” it said.

The statement was “disappointing,” Sander-Green said.

“There’s no reason to delay, the province can go ahead and get this limit set and then we can move on to figuring out how Teck is actually going to reach this limit,” he said.

Teck’s public relations manager Chris Stannell noted in a statement to The Narwhal that the company has two water treatment facilities currently treating 17.5 million litres of water per day and plans to be able to treat 47.5 million litres per day in 2021.

“We have made significant progress implementing the Elk Valley Water Quality Plan, a long-term approach to maintaining the health of the watershed,” he said. The water quality plan allows Teck to continue operating as long as the company is working toward stabilizing selenium pollution levels by 2023 with efforts to reduce levels after 2030.

Stannell did not directly respond to a question from The Narwhal asking if the company has concerns about being able to meet a possible selenium limit of 0.8 parts per billion in Lake Koocanusa.

While people, animals and aquatic life all need a little bit of selenium, “there’s a fine line of too little selenium and too much selenium,” said Myla Kelly, water quality standards manager with Montana’s Department of Environmental Quality.

When fish are exposed to too much selenium it can result in lower production of viable eggs, reduced growth, deformities and mortality, Kelly explained.

Too much selenium can also pose a risk to humans. A report released last month by the Health Professionals Advisory Board of the International Joint Commission, which focuses on transboundary water issues, notes people can experience health problems when they regularly consume more than the maximum recommended limit of 400 parts per billion per day.

“Selenosis is the condition resulting from chronic selenium intoxication; symptoms include diarrhea, nausea, fatigue, muscle aches and hair and nail damage or loss,” the report says.

Selenium was the first priority for the Lake Koocanusa Monitoring and Research Working Group when it came together in 2015 and a technical subcommittee focused on selenium was formed soon after.

The subcommittee’s work was guided by the foremost selenium experts in both the U.S. and Canada, Kelly said.

The goal was “to establish this scientifically defensible, accurate standard for selenium, a standard that we had confidence was going to protect our aquatic life,” she said.

Kelly said Montana and B.C. agreed to a 2020 timeline to bring in new standards, and given Montana’s rulemaking process that meant her department had to bring forward proposed standards this fall.

“It’s our understanding that they’re working through their process as well,” she said of the B.C. government.

In a statement, Kathryn Teneese, chair of the Ktunaxa Nation Council, said “as a government, the Ktunaxa Nation Council respects that each government at the table has their own respective timelines and processes for engagement and decision making, and we are confident there is still an opportunity to achieve the common goal for a single objective for the Koocanusa Reservoir, which will reflect the efforts that have been made on both sides of the 49th parallel in the past five years.”

In the meantime, new and expanded coal mines are being planned for the region, including Teck’s Castle Mountain project, which the company bills as an expansion of its Fording River mine — the largest coal mine in the province. The mining project would increase the area of mining operations by more than 2,000 hectares.

According to Teck, steelmaking coal from Castle Mountain would be processed at its Fording River operations for several decades.

In August, Ottawa announced that the Castle Mountain project would be subject to a federal review in addition to a provincial one after several environmental organizations, Indigenous groups and U.S. government agencies called for a more comprehensive assessment.

Numerous groups that called for the federal review raised concerns about increased selenium pollution from the mining project.

Now environmental groups are pushing for B.C. to establish the more stringent 0.8 parts per billion selenium limit before Castle or other proposed coal mining projects proceed further through the review process.

“It’s time for B.C. and Montana to both make this limit law before the pollution situation in Koocanusa gets any worse,” said Dave Hadden, the executive director of Headwaters Montana, in a joint statement with Wildsight.

Enbridge Gas will face Waterloo Region in a hearing before the Ontario Energy Board to renew an agreement that would allow the company to continue...

Continue reading

For 15 years and counting, my commute from Mississauga to Toronto has been mired by...

For our last weekly newsletter of the year, we wanted to share some highlights from...

The fossil fuel giant says its agreement to build pipelines without paying for the right...