Indigenous-led conservation plans in Manitoba have sparked backlash. There’s also a path forward

Locals in the small community of Arborg worry a new Indigenous-led protected area plan would...

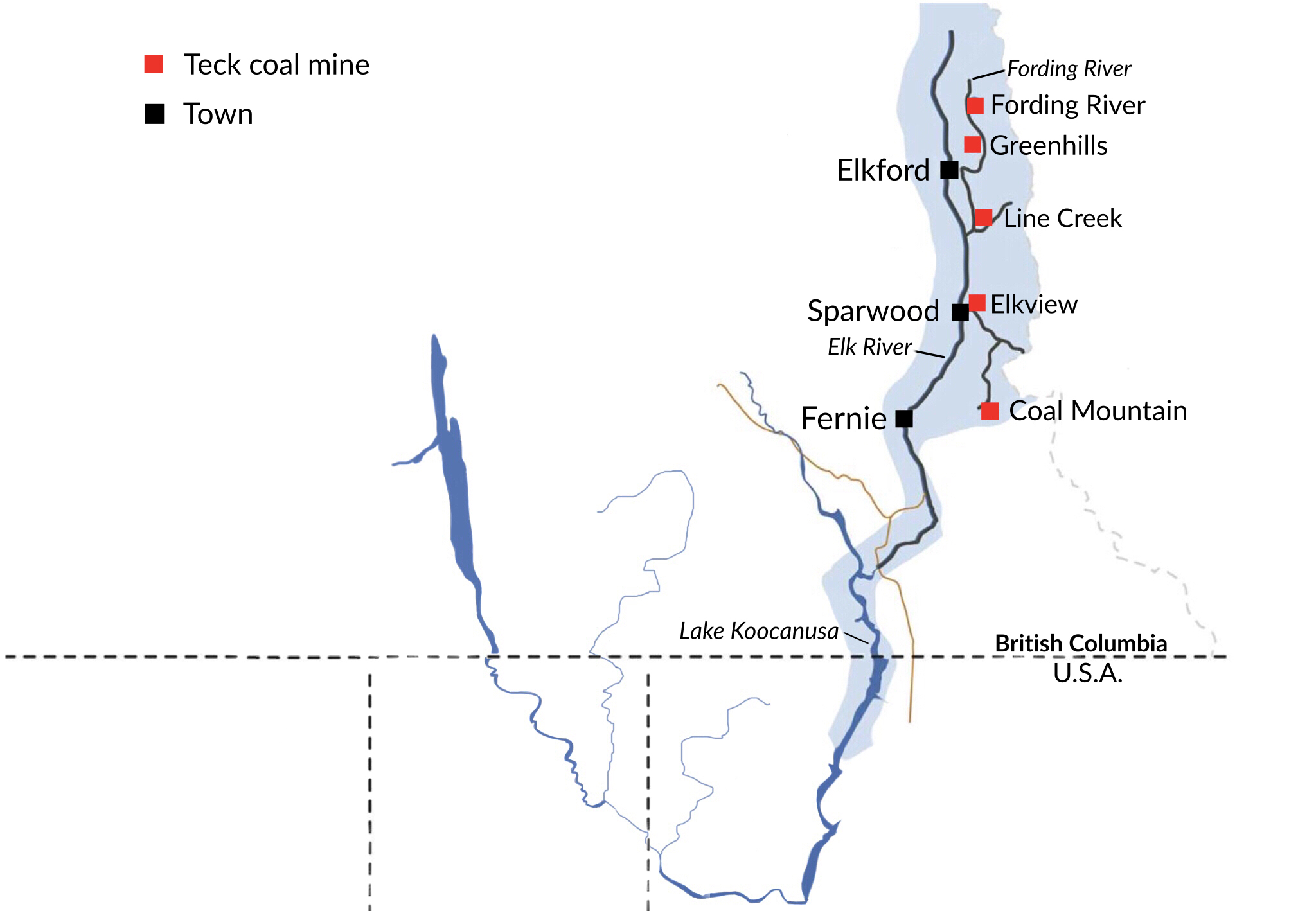

In October 2012, Ktunaxa Nation wrote to then U.S. Secretary of State Hilary Rodham Clinton and Canada’s foreign affairs minister of the day, John Baird, asking them to task an international commission with investigating cross-border pollution from a string of massive coal mines in southeast British Columbia.

The nation, whose territory spans parts of B.C., Alberta, Montana, Idaho and Washington State, was growing increasingly concerned about the threat this pollution posed to important fish populations — and Teck Resources, which owns the mines, was planning to expand its operations.

The next year, the B.C. government ordered Teck to develop a plan to address its growing pollution problems. Since then, the company has invested more than $1.4 billion in water treatment and other measures to control the contamination. At the same time, though, mining was allowed to expand and despite the company’s efforts, it continues to pollute international waterways.

After more than a decade of concerted efforts by Ktunaxa Nation to garner support for an international inquiry into the pollution, the proposal appears to be gaining traction. As Canada and the U.S. negotiate a path forward, the government of B.C., which had previously been opposed to involving an international commission, has signalled a change of heart in a move the nation called “a surprising but long overdue turn of events.”

Selenium and other contaminants were found to be rising in the Elk River in the 1990s and subsequent research pointed to the mines upstream, according to a B.C. government website that outlines the history of water quality issues in the Elk Valley. From the Elk River, the pollution flows into the Kootenay River, which passes through Montana and Idaho before returning to B.C.

Selenium occurs naturally in rocks in the Elk Valley. But when massive piles of waste rock from the mines are exposed to rain and snowmelt, the contaminant is released into the water, eventually flowing into nearby rivers and creeks.

Today selenium levels in some areas downstream of the mines are many times higher than what’s considered safe for fish and other aquatic life. In fish, the contaminant can impede reproduction and cause deformities such as curved spines, misshapen skulls and abnormal gills.

Since sending that first letter more than a decade ago, Ktunaxa Nation has written repeatedly to top diplomats in Canada and the U.S. urging them to involve the International Joint Commission in what has become a contentious issue. The commission was created under the Boundary Waters Treaty of 1909 to study and recommend solutions to intractable disputes and many saw it as the natural venue to address the pollution stemming from Teck’s coal mines.

Not everyone agreed. The coal mines are a major employer in the Elk Valley and a significant contributor to provincial GDP and both B.C. and Teck had been lobbying federal officials to quash any potential inquiry by the Canada-U.S. body, internal records obtained by Ktunaxa Nation last year revealed.

In March, the issues in the Elk-Kootenay watershed hit the national stage when Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and U.S. President Joseph Biden issued a joint statement saying the two countries would “reach an agreement in principle by this summer to reduce and mitigate the impacts of water pollution in the Elk-Kootenay watershed in partnership with Tribal Nations and Indigenous Peoples.” The intent, they said, is “to protect the people and species that depend on this vital river system.”

Just a few months later, Ktunaxa Nation Council submitted a proposal to the Canadian and U.S. governments for a two-pronged approach to addressing the widespread contamination: an International Joint Commission inquiry and a Ktunaxa-federal action plan.

There’s a need for the commission “to conduct an independent, transparent and accountable scientific assessment of pollution in the watershed and perform ongoing monitoring,” the Ktunaxa Nation Council, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes and the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho, wrote in a joint Ktunaxa Nation press release this month.

The action plan, in the meantime, would set the stage for more immediate measures to restore the rivers affected by Teck’s mines.

In a statement to The Narwhal this week, a spokesperson for the Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy said “B.C. has proposed a role for the International Joint Commission to act as a neutral third party — bringing representatives together to share progress, validate issues and facts and gather information in a way that is respectful and inclusive of Indigenous Knowledge.”

But the B.C. government says it wants to limit the scope of any inquiry to prevent duplicating scientific reviews it says it’s already doing.

“Robust scientific assessments and comprehensive environmental monitoring already exist for the B.C. portion of the watershed. The province is not supportive of any scientific study that seeks to duplicate this work and divert provincial resources from our planned and ongoing initiatives,” the ministry spokesperson said.

“Our support is contingent on the Canadian and U.S. governments accepting our proposals for a role of the [International Joint Commission] to act as a neutral convener,” it said, adding that any transboundary process must “respect regulatory authority.” The province is, however, open to adjusting its monitoring and regulatory efforts if “any significant and relevant gaps” are identified in its existing programs, the statement said.

The B.C. government is working with Ktunaxa Nation to set a new selenium standard for Lake Koocanusa, a transboundary reservoir downstream of the mines, that will inform updates to the Elk Valley Water Quality Plan and ultimately Teck’s waste discharge permits.

But for years, the nation and conservation organizations have raised concerns about the gaps in B.C.’s regulatory regime that have allowed the mine pollution to persist even as Teck’s operations have been repeatedly allowed to expand, as well as a lack of transparency around the extent of the contamination and potential harms.

“One of the key values of the [International Joint Commission] is its well-established track record as a neutral third part that is unencumbered by individual government or industry interests when it comes to stewardship of transboundary watersheds,” Ktunaxa Nation Council Chair Kathryn Teneese said in a statement to The Narwhal.

“The main outcomes we need to achieve are improving water quality and protecting ʔa·kxam̓is̓ is q̓api qapsin (all living things), including Ktunaxa cultural practice of sukiⱡ ʔiknaⱡa (eating good),” Teneese said. “We know the current regulatory regime is not achieving these important outcomes and we need to tighten things up, learn from past mistakes, improve existing measures and address any gaps.”

“While we appreciate that B.C. is now welcome to [International Joint Commission] involvement and has provided its views via a proposal, the final [International Joint Commission] reference is a transboundary matter decided at the federal level, with deep engagement with Ktunaxa,” she said.

“As stewards of this place for more than 10,000 years, there can be no solutions or assessment of this watershed without deep and meaningful partnership with the Ktunaxa ʔaqⱡsmaknik,” Teneese said in the joint press release this month.

Randal Macnair, the Elk Valley conservation coordinator with the Kootenay-based conservation organization Wildsight and a former mayor of the largest Elk Valley community, told The Narwhal the “two-pronged approach the Ktunaxa are taking is exactly the sort of thing that needs to happen.”

“If the provincial government and the federal government are really committed to reconciliation, what happens with this situation will be telling,” he said.

In a statement a spokesperson for Global Affairs Canada said the federal government “is strongly committed to protecting freshwater resources, including in the Elk Valley.”

Discussions are ongoing between government officials and Indigenous nations and tribes towards reaching an agreement to address the Elk-Kootenay watershed, the statement said.

“We are committed to these ongoing efforts to work together to find an appropriate path forward to ensure the health of the watershed,” it said.

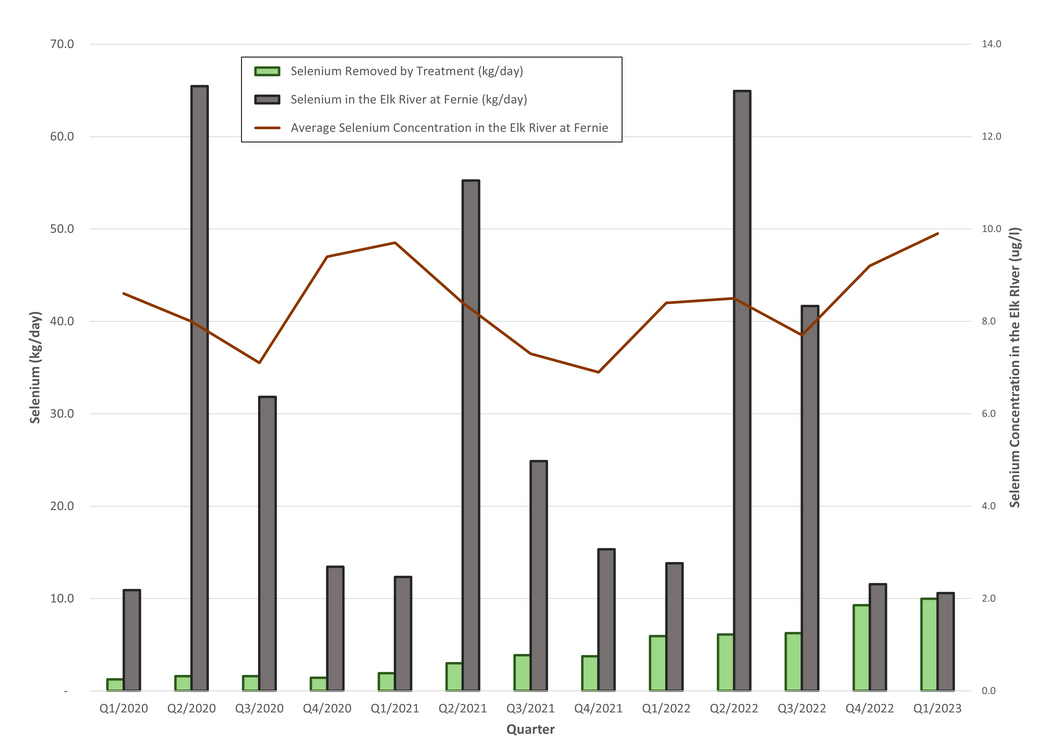

The task ahead — to stem the flow of pollution from the Elk Valley mines — is immense. Teck has already invested more than $1.4 billion in water treatment and other measures to address the contamination. Despite some initial issues, the treatment plants are removing between 95 and 99 per cent of selenium from the water they treat, according to the company.

But the majority of both selenium and nitrate pollution from the mines still flows downstream without any treatment at all, according to information on a new provincial website, called the Elk Valley Water Quality Hub.

And while average monthly selenium levels in the Fording and Elk rivers downstream of Teck’s mines fell mostly within the limits outlined in the company’s permits during the first quarter of this year, those limits are between nine and 30 times higher than the levels considered safe for aquatic life.

In a statement to The Narwhal, Chris Stannell, Teck’s public relations manager, said the company is “making significant progress” on water quality issues in the region.

“Monitoring shows selenium concentrations have stabilized and are reducing downstream of treatment,” he said, adding there plans to expand treatment capacity over the next five years.

But Erin Sexton, a senior research scientist with the University of Montana’s Flathead Lake biological research station, warned one of the key challenges with understanding the impacts of the mine pollution in the Elk-Kootenay river system is that the data and modelling Teck relies on to state that its treatment plants are working isn’t available for independent, third party review.

“Let’s put in place a watershed board and bring all that data to the table and let a third party evaluate whether or not that assessment is actually accurate,” she said.

There are signs downstream that the problem persists — selenium levels in the tissue of multiple fish species are increasing, Sexton said.

Some 100 kilometres from the mines, the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho is concerned about the impacts to endangered white sturgeon and burbot populations the tribe has spent years trying to rebuild.

“We see our fish populations declining despite our own hatchery efforts to sustain them,” Gary Aitken Jr., the tribe’s vice chairman, said in the joint Ktunaxa Nation press release. “We are watching our river suffer as the regulators stand by and watch.”

“There is an immediate need for action to begin restoring these waters that are so central to the Ktunaxa people,” Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes Chairman Tom McDonald said in the joint release. “Now all we need is for Canada and the U.S. to sign onto the Ktunaxa proposal so we can get to work.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On March 17, federal Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre...

Continue reading

Locals in the small community of Arborg worry a new Indigenous-led protected area plan would...

Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre says he’ll fast-track approvals and scrap key rules that protect the...

One LNG project alone is requesting more than half the amount of electricity B.C.’s Site...