The Narwhal’s in-depth environmental reporting earns 11 national award nominations

From disappearing ice roads to reappearing buffalo, our stories explained the wonder and challenges of...

Teck Resources got a heads up more than a year ago that one of its southeast B.C. coal mines was under investigation for allegedly violating Canada’s Fisheries Act.

The company knew charges could be coming.

But it wasn’t until July 10, the day before Teck closed a deal to sell its Elk Valley coal mines, that Environment and Climate Change Canada laid charges against the company for polluting two fish-bearing waterways in the East Kootenay region of B.C.

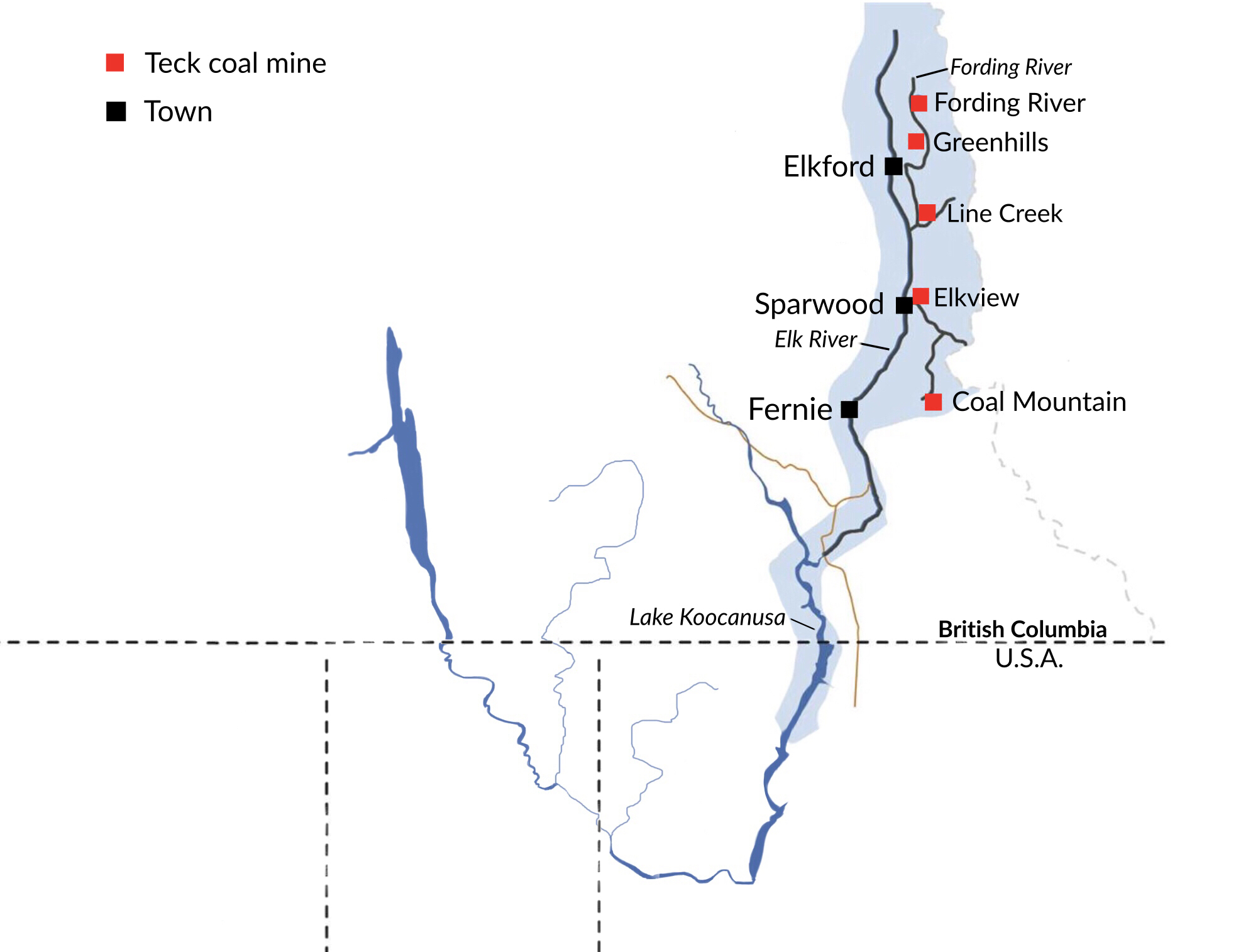

The federal department filed five Fisheries Act charges against the company’s coal subsidiary over pollution from the Line Creek Operations. Line Creek is one of four active coal mines now majority owned by Swiss mining giant Glencore and operated under a new name: Elk Valley Resources.

The charges come more than three years after Teck pleaded guilty to similar charges over pollution from its Greenhills and Fording River mines. In that case, the company was ordered to pay $60 million in penalties — the largest fine ever issued for Fisheries Act violations — for releasing contaminants into fish habitat.

“Everytime something happens, we the public, the province and even those of us in this community get assurances that … ‘We’ve got a handle on this’ — and they don’t,” Randal Macnair, Elk Valley conservation coordinator with the non-profit group Wildsight, said in an interview.

“We don’t take any joy in Teck polluting our rivers,” he said. “When is this going to end?”

Here’s what you need to know about the latest Fisheries Act charges.

The latest charges allege Teck Coal violated section 36, subsection three of the Fisheries Act. What does that mean, exactly? Well, Environment and Climate Change Canada alleges the company released — or allowed the release of — what’s known as a “deleterious” substance (more on that in a minute) into Dry Creek and the Fording River between January 2018 and September 2023.

Dry Creek runs through part of the Line Creek Operations before flowing into the Fording River, which is itself a tributary of the Elk River.

What’s a “deleterious” substance, you ask? It’s any substance, such as oil or pesticides, that when added to water can degrade water quality to the point of harming fish, according to Environment and Climate Change Canada.

One charge laid against Teck Coal relates to leftover waste rock from the coal mines, according to information filed with the provincial court in Cranbrook, B.C. The other four charges reference “coal mine waste rock leachate” — contaminants that drain from waste rock piles exposed to air, rain and snowmelt.

In response to a request for comment, Doug Brown, Teck’s vice-president of corporate affairs, directed The Narwhal to Glencore and Elk Valley Resources, which assumed responsibility for the coal mines on July 11.

Though the charges name Teck Coal, it’s Elk Valley Resources that will shoulder the liability, according to Charles Watenphul, a spokesperson for Glencore, which newly owns a 77 per cent interest in Elk Valley Resources.

“These charges were laid against the Elk Valley Resources business, which will be liable for any penalties payable,” Watenphul said in a statement to The Narwhal.

“We will not comment further on ongoing legal matters,” Watenphul said.

Asked whether the charges may be amended to name Glencore or Elk Valley Resources, a spokesperson for the Public Prosecution Service of Canada said in an emailed statement “the charged party on the information is Teck Coal and at this time the Crown is proceeding with those charges.”

Teck Coal is due to make a first appearance in B.C. provincial court in Fernie, B.C., on Aug. 15.

In the previous case Environment and Climate Change Canada brought against Teck, the company was also charged with violating section 36, subsection three of the Fisheries Act — the same as in this new case. That first case centred around selenium, an element that can be toxic for fish, and calcite, which can harden the loose, gravelly streambeds fish use to create protective nests for their eggs.

Teck pleaded guilty to two charges related to pollution from its Fording River and Greenhills operations over the course of 2012 in that case. Crown prosecutors agreed not to pursue charges related to releases of the same contaminants from those mines between 2013 and 2019.

At the time, the judge in the case said he was “satisfied the penalties imposed are a significant deterrent to Teck Coal.”

But Macnair, who is also a former mayor of Fernie, questions the impact of even a $60-million fine for a company earning billions of dollars from the mines.

“It’s obvious that Teck is taking this as a cost of doing business,” he told The Narwhal.

Fisheries Act violations can lead to fines or imprisonment. In the previous case against Teck, the company was fined $1 million and ordered to pay $29 million into the federal government’s environmental damages fund for each of the two charges. The fund supports projects — usually in the area where damages occurred — that have a positive impact on the natural environment in Canada.

The mines, which produce metallurgical coal that is later burned to make steel, were big earners for Teck. In 2023 alone, the company made a gross profit of $4.03 billion from its coal business.

Teck is now shifting its focus to copper, which is required for the global transition to a low-carbon economy. And, after a failed attempt to spin off its coal business as a separate company and fending off a hostile takeover bid by Glencore last year, Teck agreed to sell.

For years, water pollution from Teck’s coal mines has been a pressing concern for downstream communities throughout Ktunaxa territory, which spans parts of B.C., Montana and Idaho.

In a statement, Ktunaxa Nation Council Chair Kathryn Teneese said the council, which represents four Ktunaxa First Nations, was happy to see the new charges laid.

“We are pleased to see Canada upholding their legislation and commitments to the environment through these charges,” Teneese said, adding, “a lot of money was made during the time that the damages were occurring.”

“The Ktunaxa Nation has spent decades working to improve water quality and reduce pollution from Teck’s coal mining in the Elk and Kootenay River systems,” Teneese said.

In the previous case against Teck, the court recommended a portion of the $60-million penalty be directed to First Nations in the Kootenay region for fish conservation and restoration.

If the new charges result in fines or penalties, Teneese said the nation is “hopeful that the funds will come back to ʔamakʔis Ktunaxa [Ktunaxa territory], to be used by Ktunaxa to repair at least some of the damage done and to help us uphold our stewardship responsibilities to ʔa·kxam̓is q̓api qapsin (all living things).”

Macnair called it “a bit demoralizing” to live in the Elk Valley “with an entity that has obviously expressed a lack of regard for the way business should be done and a lack of regard for our environment.”

“We want to give Teck the benefit of the doubt, we want them to be doing a good job and they demonstrate again and again and again that they aren’t meeting the basic operating requirements of a mine and it’s just very frustrating,” he said.

“It doesn’t make us feel any more comfortable having Glencore taking over,” he added.

Coal has been mined from the Rocky Mountains in southeast B.C. for more than a century and the mines are a major contributor to the regional economy. At the same time, there are long-standing concerns about the environmental harms the mines have wrought in Ktunaxa Nation territory.

To access the coal, Teck has systematically stripped away mountaintops in a process that produced massive amounts of leftover waste rock. When that waste rock was exposed to air, rain and snowmelt, selenium and other naturally occurring minerals leached into the water, flowing into nearby creeks and rivers.

Teck invested more than $1.4 billion in water treatment and other measures to address the pollution. But selenium levels in the Fording and Elk rivers downstream of the mines remain many times higher than what the provincial government considers safe for aquatic life and there are widespread concerns about the risk the contamination poses for fish.

Though selenium is essential for life, too much can be toxic. When female fish transfer the contaminant through their eggs, their larvae may be born with deformities — curved spines, misshapen skulls, abnormal gills — or fail to hatch at all.

While Teck mostly met its selenium limits at monitoring sites downstream of mines over the past several years, the company repeatedly exceeded selenium limits during the late winter or early spring, according to data from January 2022 to March 2024 posted to the Elk Valley water quality hub. And even when selenium levels are within permitted limits, they remain many times higher than what the provincial government considers necessary to protect aquatic life.

In his statement to The Narwhal, Watenphul noted Elk Valley Resources has made progress in implementing the Elk Valley water quality plan, which Teck was ordered to develop just over a decade ago to address water pollution from its mines. He said Glencore will honour its commitment to continue investments in treatment and other measures to improve water quality.

For more than a decade, Ktunaxa Nation, which includes four First Nations in B.C., the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes in Montana and the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho, pressed the federal governments in both Ottawa and Washington, D.C., to refer the issue to the International Joint Commission.

The commission was established under the 1909 Boundary Waters Treaty to address intractable disputes over transboundary waters. It wasn’t until this year that the Canadian and United States governments asked the commission to launch an inquiry.

A governance body — made up of the Canadian and U.S.federal governments, Ktunaxa Nation, the B.C. government and the states of Montana and Idaho — has been established to guide the process. An expert study board will be established this fall and asked to develop a final report and recommendations by the fall of 2026.

While the inquiry process will take time, Macnair said he’s “quite optimistic.” A key reason for that optimism, he said, is that Ktunaxa Nation has “an influential seat at the table.”

But despite the assurances from Glencore, Macnair said he’s not feeling “terribly optimistic” about the new owner of the mines.

“We’re hearing a lot of hopefulness about Glencore, but unfortunately [for] those of us who have had a chance to delve into their record, we’re not terribly optimistic,” he said.

In his statement to The Narwhal, Watenphul reiterated the commitments Glencore made to the federal government — which approved the coal business purchase under the Investment Canada Act — to continue to improve water quality downstream of the mines.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

From disappearing ice roads to reappearing buffalo, our stories explained the wonder and challenges of...

Sitting at the crossroads of journalism and code, we’ve found our perfect match: someone who...

The Protecting Ontario by Unleashing Our Economy Act exempts industry from provincial regulations — putting...