Rocky Mountain coal mine in Alberta takes next step to expansion

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

Frustrated U.S. representatives on a commission tasked with protecting the quality of water flowing across the Canada/U.S. border have gone public with claims that Canadian commissioners are refusing to accept scientific data that shows an increase in selenium pollution from B.C.’s Elk Valley coal mines.

Two U.S. commissioners on the International Joint Commission have released a letter to the U.S. State Department that says Canada’s three representatives on the commission will not endorse a recent report that shows risks to aquatic life and humans from selenium pollution from five Teck Resources Ltd. coal mines.

It’s a highly unusual move, suggesting a rift among the usually non-partisan representatives of the international body.

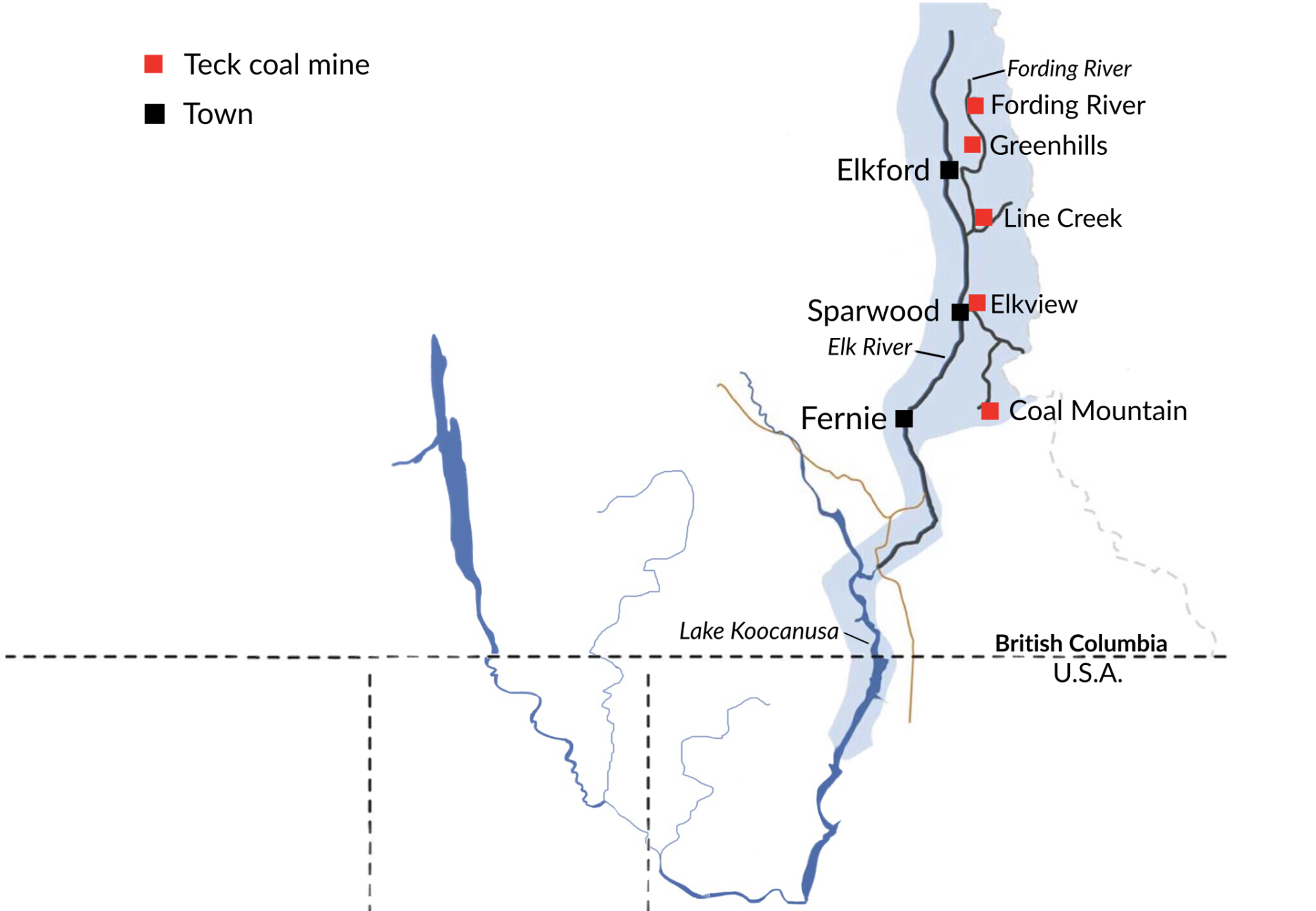

The polluted water, which leaches from massive amounts of waste rock at Teck’s metallurgical coal mines, flows into the Elk and Fording Rivers in B.C., then into the Koocanusa Reservoir which straddles the border and finally into the U.S. Kootenai River before curling back up into Canada at Creston.

Teck’s five metallurgical coal mines are all upstream of the transboundary Koocanusa Reservoir.

“In addition to the short-term impacts, it is well understood that high concentrations of selenium will have long lasting impacts on water quality, fish, other aquatic species, wildlife and human health in southeast B.C. and northwestern Montana communities,” says the letter from Lana Pollock, chair of the commission’s U.S. section, and commissioner Rich Moy.

“These impacts could become permanent.”

In addition to selenium, other significant pollutants from the exposed waste rock include nitrates, sulfates and cadmium.

The two Canadians on the commission are Gordon Walker, a non-practicing Toronto lawyer, and Montreal government and private sector consultant Richard Morgan. Decisions made by the International Joint Commission are non-binding, but usually accepted by governments.

A commission spokesperson could not be contacted prior to publication.

The study creating the rift looks at selenium impacts on human health and took six years of work by contractors and commission staff, but the Canadian contingent wanted to submit an earlier report that excluded recent data from Teck and Environment and Climate Change Canada, says the letter.

“Canadian Commissioners have not been willing to submit a report that addresses selenium pollution in transboundary waters of the Kootenai River drainage,” said the letter, which points out that selenium will continue to pollute the Elk and Kootenai transboundary waters for hundreds of years if no solution is found.

“U.S. Commissioners have been unwilling to endorse a report that lacks accurate and available information relevant to health impacts in the transboundary Elk/Koocanusa watersheds from the Teck coal mines,” the letter further stated.

Studies have found that high selenium concentrations are resulting in deformities and reproductive failure in trout and fish mortality of up to 50 per cent in some portions of the Elk watershed, according to Pollock and Moy.

In 2014 Teck introduced the $600 million Line Creek water treatment plant to address selenium pollution but the facility unintentionally released a more bioavailable form of selenium into the watershed. After four months of operation the facility caused a substantial fish kill and in 2017 the company pled guilty to violations of the federal Fisheries Act and was ordered to pay a $1.4 million fine.

The water treatment plant remains offline as Teck seeks a solution.

“There is a question as to whether the technology even exists to remove selenium from large volumes of flowing water and there is no viable solution to remove selenium from groundwater,” the commissioners wrote.

As a final kicker, the letter says B.C.’s negligence in addressing the mining impacts puts Canada at risk of violating the Boundary Waters Treaty of 1909.

That is a conclusion also drawn in 2016 by B.C. Auditor General Carol Bellringer, who, in a scathing report, said the Environment Ministry has been monitoring dramatic increases in selenium levels in the Elk Valley for 20 years, but, with a lack of regulatory oversight, has taken no substantive action to solve the problem and has not publicly disclosed the risks of continuing to issue permits for coal mines in the Elk Valley.

“As selenium accumulates up the food chain, it can affect the development and survival of birds and fish and may also pose health risks to humans,” Bellringer wrote.

Teck spokesman Chris Stannell said the company worked with governments, Indigenous groups and scientific experts to come up with the Elk Valley Water Quality Plan, which is “a comprehensive, long-term approach to address the management of selenium and other substances released by mining activities throughout the Elk Valley watershed.”

Extensive monitoring has found selenium and other substances are not affecting fish populations, Stannell said.

However, in their letter to the U.S. state department commissioners Pollack and Moy found selenium pollution has resulted in “deformities and reproductive failure in trout and increasing fish mortality of up to 50 per cent in some portions of the Elk and Fording watersheds.”

In addition, they write, “mine pollutants are poisoning and killing off the more sensitive species of macro-invertebrates downstream of the mines.”

Instead of improving water quality, Teck’s Line Creek Treatment facility may have made it worse, Pollack and Moy found.

Stannel said the company will invest between $850 million and $900 million during the next five years towards construction of water treatment facilities, the second of which is now under construction.

Critics point out that it is clear that Teck is unable to meet commitments made in the Water Quality Plan, such as selenium, nitrate and sulphate levels and that the company’s previous water treatment plant remains shut down. They also point out much of Teck’s raw baseline data on selenium contamination is not made available to the public, a hazard of the province’s professional reliance system, which is currently under review.

Teck is also a frequent flyer on the province’s environmental enforcement penalty list, most recently showing up on the list for the last six months of 2017 which shows three penalties, with fines of $78,100, for failing to comply with an effluent discharge permit and then failing to report the problem.

Teck has received about $2 million in fines and penalties for various provincial and federal environmental violations over the past five years, said Environment Ministry spokesman David Karn.

“The ministry has heightened compliance attention in the Elk Valley and all of Teck Coal’s operations are inspected at a minimum of once per year, with the Valley Wide Permit inspected approximately 10 times per year,” he said in an emailed response to questions from The Narwhal.

While levels for selenium, nitrate and sulphate appear to be stabilizing in the Koocanusa Reservoir and Elk River, Teck was recently found to be out of compliance with selenium levels at Lake Koocanusa and the file has been sent to the Conservation Officer Service for investigation, Karn said.

The ministry is aware of meetings taking place in Washington, D.C. between the U.S. State Department and Global Affairs Canada to discuss the selenium issue, Karn said.

Also, B.C. and Montana are developing an agreement to work through a monitoring and research committee to set a water quality objective for selenium for the Koocanusa reservoir,” he said.

“Presently, the selenium guidelines set by Montana are being met in the reservoir, but future targets are expected to be lower,” he said.*

“What we need to do is hold the company accountable for the damages.”

-Erin Sexton, biologist

Erin Sexton, senior scientist at the Flathead Lake Biological Station at the University of Montana, is encouraged the commissioners have spoken out.

“This is the first time I have ever seen something from a sitting commissioner. They have a long history of being a non-partisan, scientific body and it says to me that all the data on this watershed needs to be publicly available and open for analysis,” said Sexton.

“What I read is an accusation that the Canadian commissioners have been omitting data from what are supposed to be non-partisan reports,” she said.

Sexton is hoping the dispute does not disintegrate into finger-pointing between the two countries and that governments realize that the watersheds must be managed as a whole, regardless of boundaries.

“Really what we need to do is hold the company accountable for the damages. It looks to me like we have a bad actor here in Teck Coal and that we have a regulatory government that has been asleep at the wheel,” she said.

Sexton, who has sat in on some permitting processes, said B.C. missed a clear opportunity in 2014 when Teck wanted to expand the mines.

The province could have pressed pause and refused to issue expansion permits until the company was able to demonstrate that water quality would be improved, she said.

“Instead Teck received permits for four of their five mine expansions. Now it’s 2018 and we are looking at increasingly worse water quality trends,” said Sexton, who would like to see a hold on mining until solutions are found.

Passive water treatment, instead of water treatment plants, is probably the way forward and that means keeping waste rock out of the river, but it is difficult to achieve on the huge scale that would be necessary in the Elk Valley — and restoration would be expensive, Sexton said.

Three applications for coal mines from other companies are currently in the initial stages, and it is extraordinary that B.C. is considering allowing more mines in the area when all the levels show pollution in the watershed is far beyond the limits for protecting aquatic life, Sexton said.

Randal Macnair, Wildsight conservation coordinator for the Elk Valley, said the industry is spending money in an attempt to solve the problem, but government should take a stronger role in protecting the rivers, especially after seeing the auditor general’s report.

“Industry is going to do what industry does, but government needs to really stand up and pay attention — both the federal and provincial governments,” said Macnair, who is hoping the commissioners’ letter will make a difference.

“This is one of the oldest treaties between our two countries, so this is something we have to take extremely seriously. We have made commitments and if the proverbial shoe was on the other foot, we wouldn’t want our American neighbours sending contaminated water into our water courses,” he said.

“We have a moral obligation to take care of the resources around us.”

Ugo Lapointe of MiningWatch Canada wants the NDP government to launch a public inquiry into why the problem was not addressed for more than a decade.

“They have to make sure they never repeat the same mistake in any other B.C. watershed and, we need to get to the bottom of the Elk Valley disaster. We have centuries of pollution ahead of us and we need to know how the regulatory regime failed,” said Lapointe, adding that the first step should be a moratorium on any mining expansion in the valley.

Problems in the Elk Valley echo concerns of residents of Southeast Alaska who, for decades, have been faced with B.C.’s Tulsequah Chief Mine leaching acid mine drainage into a tributary of the salmon-rich Taku River.

Alaskans now watch with trepidation as 11 mines are proposed or already permitted near the B.C./Alaska border.

Groups such as Salmon Beyond Borders have asked the International Joint Commission to investigate threats from the B.C. mines, saying lack of oversight from B.C. puts Alaskans at risk of having to cope with the destruction of salmon runs, but, so far, the request for the commission’s intervention has not been successful.

US IJC Commissioners Letter to Dept of State on Selenium Report by The Narwhal on Scribd

*Update: July 5, 2018 11:41am pst. This article was updated to include comment from B.C. Environment Ministry spokesperson David Karn.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. A $335 million funding commitment to fund...

Continue reading

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

A trade war could help remake B.C.’s food system, but will family farmers be left...

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...