The plan to protect an area five times the size of Nova Scotia

In this week’s newsletter, reporter Emma McIntosh talks about a trip to far northern Ontario...

Stu Barnes’ earliest fishing memories are of handline fishing for salmon with friends at age seven, at the junction of the Skeena, Kispiox and Bulkley rivers in northwest B.C.

“It was our childhood place to go,” Barnes, who’s Gitksan from the First Nation community of Kispiox, says. Whether eaten fresh, filling up smokehouses or being packed in jars for winter, sockeye salmon is as much a fixture in Kispiox as the long-admired totem poles standing in the grass at the edge of the community.

With its 27 lakes and 70 spawning sites, the Skeena watershed is a haven for fish and fishing communities alike. For 5,000 years, Skeena River salmon have provided a critical food source for three First Nations across 17 communities. After decades of decline, salmon returns in the Skeena were at their highest in 20 years last year, but Barnes is still concerned about the low Pacific salmon returns across B.C. watersheds that have strained Indigenous communities, for whom salmon is important not just as a source of food but also for connection to place and culture.

“We have the right to fish, but with no fish, there’s no right. We don’t leave when the fish are gone. We have to live with the results of taking too much,” says Barnes, who is chair of the Skeena Fisheries Commission, which represents three Indigenous nations along the Skeena River, and also sits on the executive council of the First Nations Fisheries Council of British Columbia.

The federal government isn’t ignoring the salmon problem entirely. Last year, the country’s fisheries regulator, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, issued extensive closures to commercial Pacific salmon fisheries. In June 2021, the department also pledged $650 million “to stem the devastating historic declines in key Pacific salmon stocks.”

But temporary commercial fishery closures are unlikely to fix such a long-standing, systemic problem. Scientists and fishing communities want to know why Canada has yet to apply its premier tool — the Species At Risk Act — to clearly dwindling fish populations.

Canada’s Species At Risk Act became law in 2004. With it came formal recognition of the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, an independent panel that provides advice to the Minister of Environment and Climate Change. The committee makes recommendations about which wildlife to list on the species at risk registry by assessing at-risk species under four categories: endangered, threatened, special concern or extirpated, meaning locally extinct.

After a committee recommendation, the minister responsible must provide an official response, deciding whether to list a species on the registry, which has the same four risk categories. For species listed as endangered or threatened, federal protection and recovery measures kick in. Three departments share this responsibility: Environment and Climate Change Canada and, when relevant, Parks Canada and Fisheries and Oceans Canada. Every stage of this process — from initial committee assessment, to decision-making by the responsible minister, to protection planning, to implementation — is time-consuming.

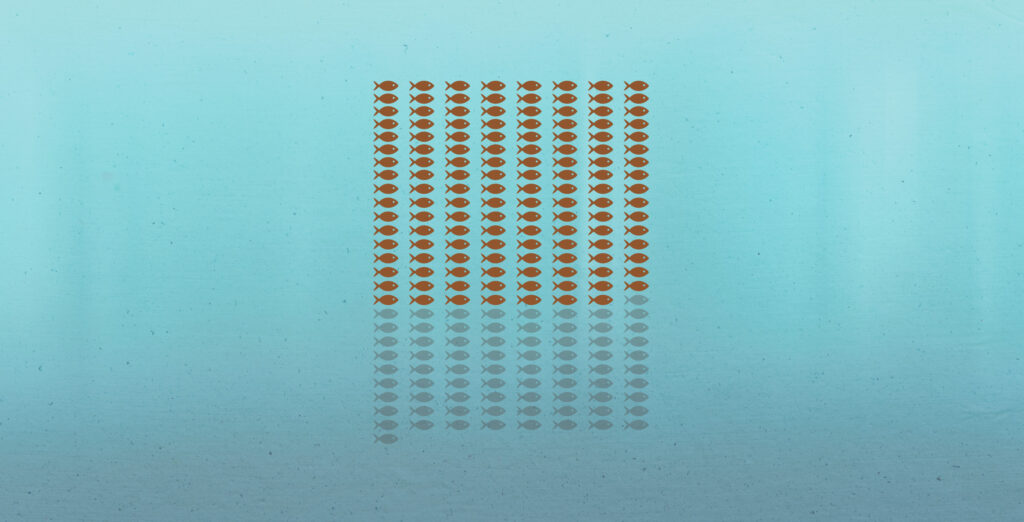

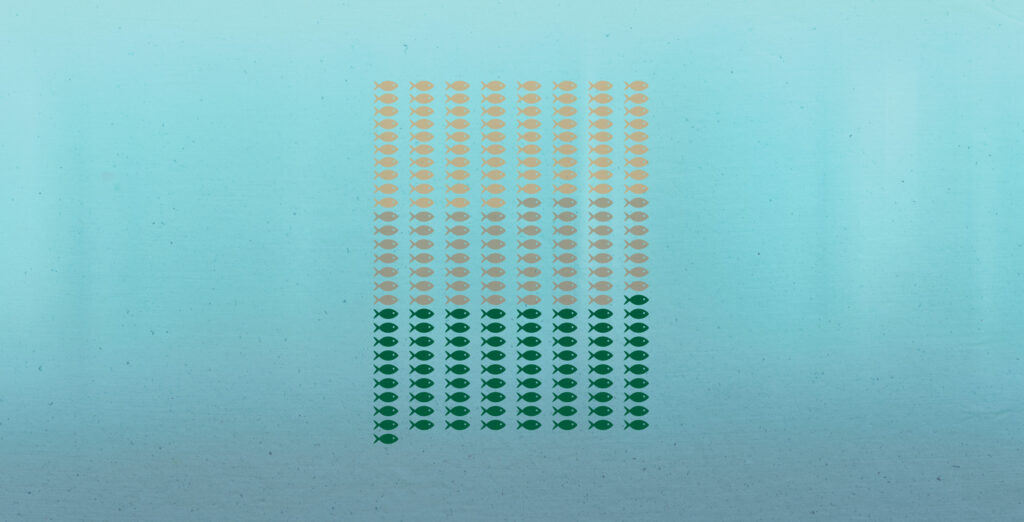

Pacific salmon, one of the most commercially important fish in the country, has never been listed on the species at risk registry. Overall, the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada has found 48 populations of Pacific salmon and trout — which are the same genus and family — are at risk of disappearing. But only three of the species scientists are worried about are listed, and all are trout species not considered commercially valuable.

An investigation by The Narwhal has found that the more commercially lucrative a fish species, the less likely it is to be protected under Canada’s species at risk legislation. That holds true regardless of how at-risk fish species or populations may be.

The Narwhal examined 209 fish species assessed as endangered, threatened or special concern by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada and analyzed each for overlap with the species at risk registry’s aquatic list. We then determined the commercial value of fish species by consulting Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s commercial fisheries website. The methods and results of this work were reviewed by two former chairs of the endangered wildlife committee: Jeffrey A. Hutchings of Dalhousie University (who passed away at the beginning of this year) and Eric Taylor of the University of British Columbia.

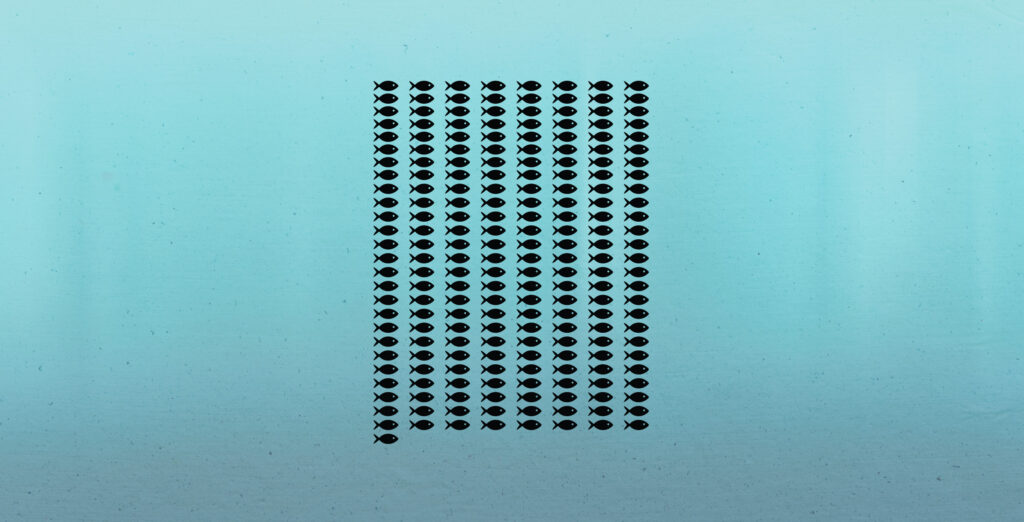

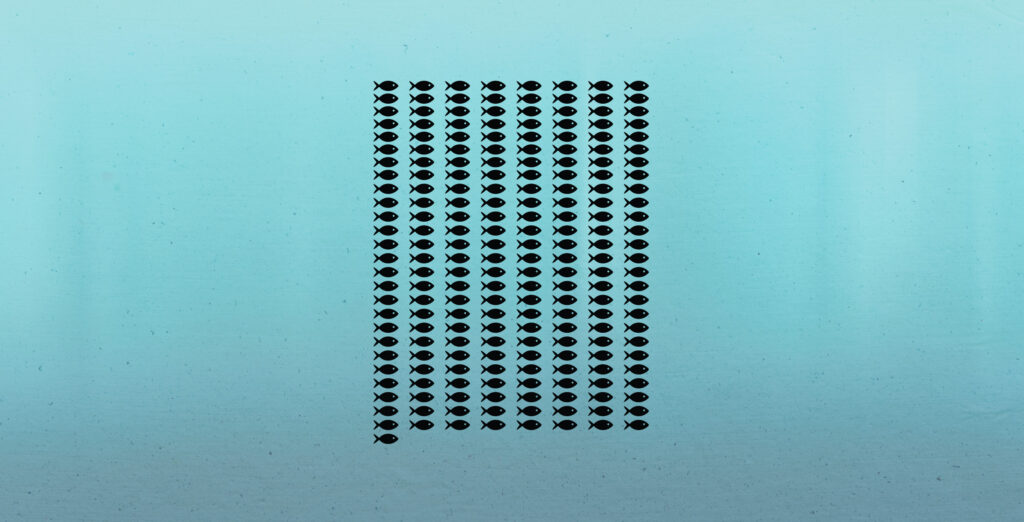

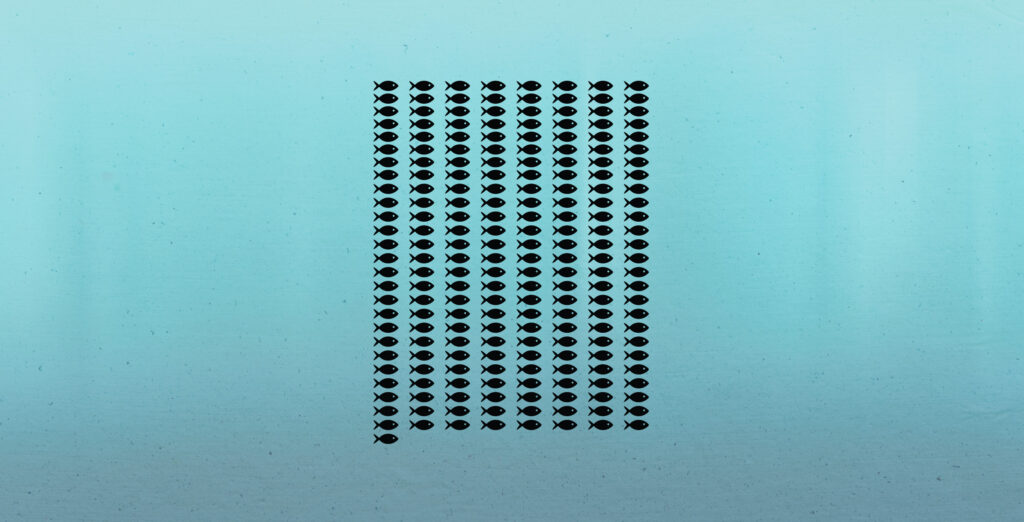

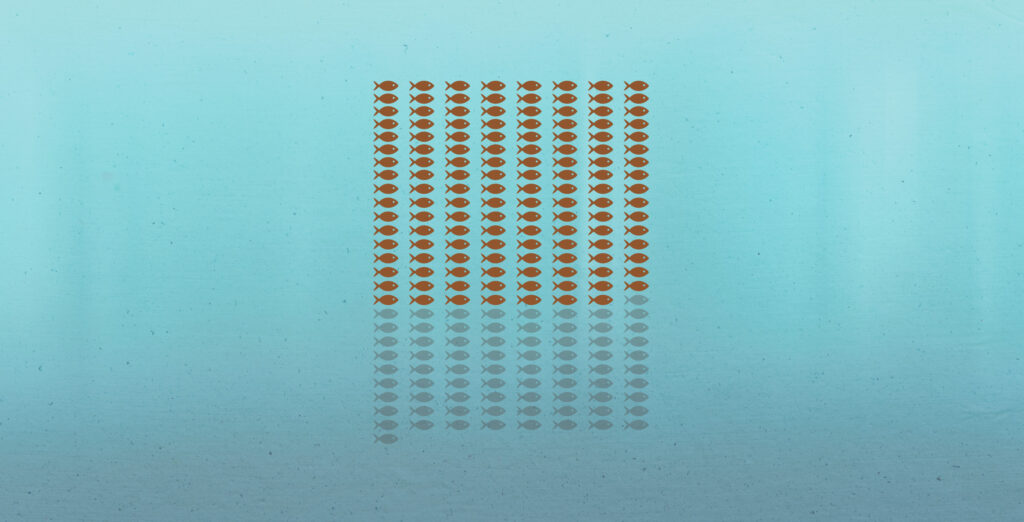

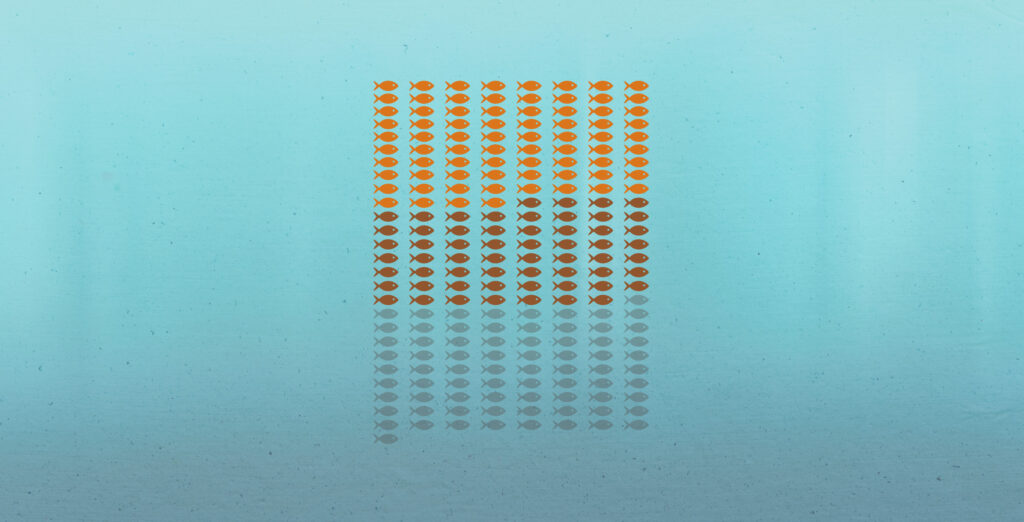

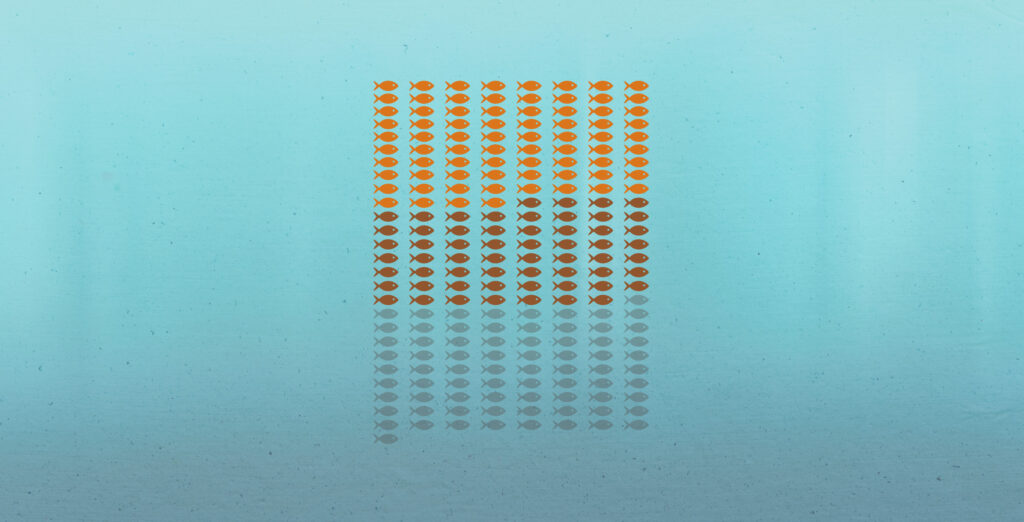

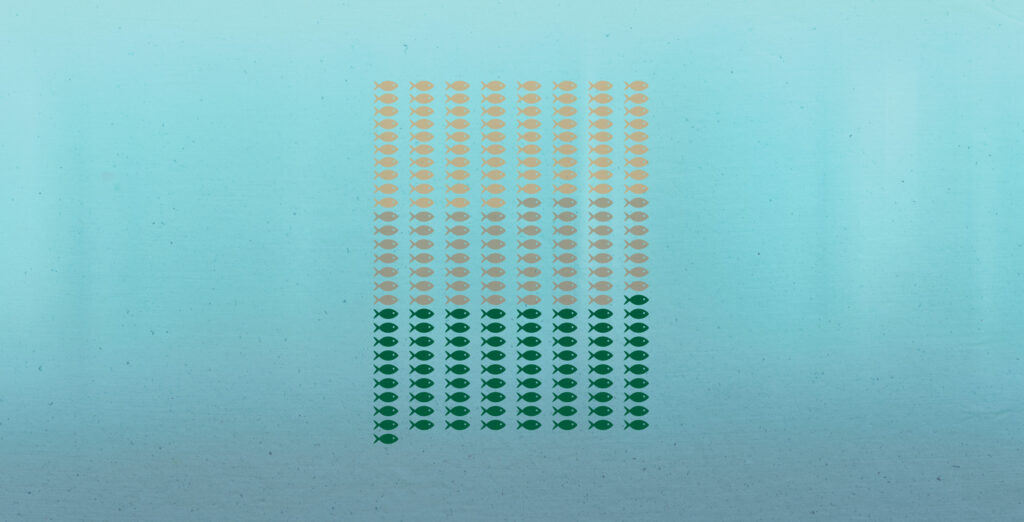

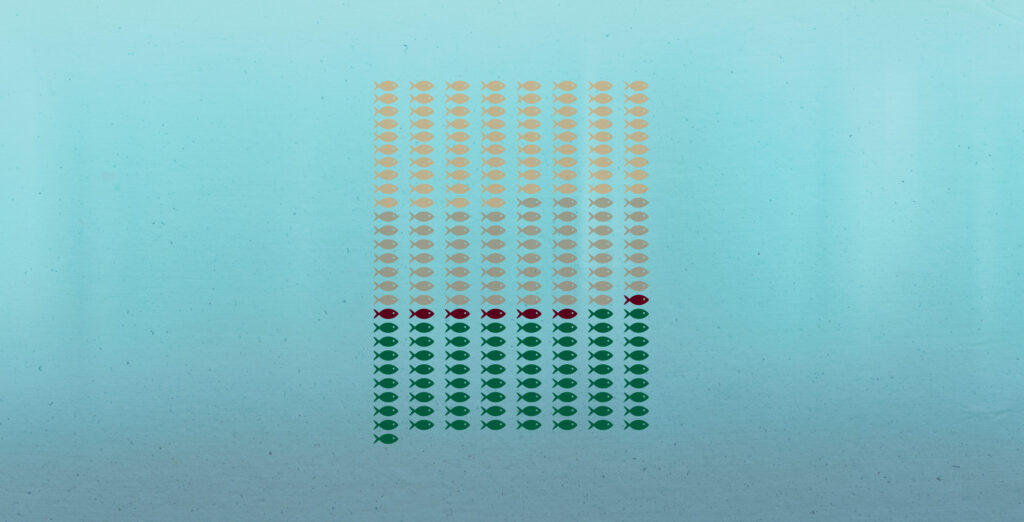

Examining all 209 Canadian fish species assessed at risk, including Pacific salmon, our investigation found:

These findings are similar to those in an October report from the Office of the Auditor General of Canada. That audit reviewed a smaller sample — 12 aquatic species or populations assessed as being at risk. Like The Narwhal, the federal auditor’s office concluded Fisheries and Oceans Canada is failing to protect commercially valuable fish species at risk, finding the department’s approach to protecting aquatic species under the Species At Risk Act “contributed to significant listing delays and decisions not to list species with commercial value.”

The report supports key findings from The Narwhal’s analysis pointing to bias against listing commercially valuable species.

The federal government did not respond to questions about this perceived bias when responding to emailed questions from The Narwhal.

“Our government is focused on protecting aquatic species at risk, and that means accepting the commissioner’s findings, while reducing delays to list those species,” Kevin Lemkay, director of communications for Fisheries Minister Joyce Murray, wrote in an email.

The Narwhal found that while 74 out of 209 species assessed as at risk by the committee are considered commercially valuable, only seven of those 74 are listed on the federal species at risk registry.

That means of the 209 fish species assessed at risk by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, 60.2 per cent, or 126 species, are designated by the federal government as having “no status.” This means that the government has opted not to list the fish, has said there is inadequate information to make a decision or a decision about whether to list remains pending, which can last as long as a decade.

Many of the commercially valuable fish species that don’t have federal protections, despite being considered at risk by endangered species experts, are delicious when battered and served with tartar sauce or grilled and folded into tacos, including Pacific salmon, Atlantic cod and Atlantic Bluefin tuna.

The total value of all commercially relevant fish species assessed as at risk by the endangered wildlife committee but not recognized under the Species At Risk Act was over $135 million in 2020, the most recent year for which data is available.

Wildlife assessed by the endangered species committee as at risk are already in dire situations and their habitats are often compromised. If left unaddressed, independent scientists say these imperilled species can disrupt entire food chains or ecosystems.

Then there’s the human and economic outfall. Millions of people are dependent on Canada’s wild fish and the fisheries they support. It’s fundamental to the lives and livelihoods of coastal communities, many of which are Indigenous.

One of the experts who reviewed The Narwhal’s findings was Eric Taylor, a professor of zoology at the University of British Columbia and a former member of the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. The committee’s chair from 2014 to 2018, Taylor says he recognizes the pattern showing up in The Narwhal’s investigation.

Commercially fished or hunted animals “tend to have a much lower probability of protection,” Taylor, who was on the committee for about 15 years, says.

“We’re not using the main legislative tool we have to protect species that are at risk of extinction, which is the Species At Risk Act,” he says. “By not listing … salmon under federal legislation that is specifically designed to recover species at risk of extinction, it clearly demonstrates we’re not doing enough.”

John Reynolds, a biology professor at Simon Fraser University, is the committee’s current chair. In an interview, he said it can be difficult to assess the value of protecting a species.

“Where things can go somewhat astray is in trying to put meaningful numbers on how much it would cost to list a species and especially in calculating the benefits,” Reynolds says.

He points to a 2013 paper by a group of researchers from Simon Fraser University, entitled “What is an endangered species worth?” It found that when determining whether to list a fish species under the Species At Risk Act, the federal government gives less weight to threat status than to the financial costs of conservation decisions, such as lost jobs and income from fishery closures or the costs of protections. This was especially true of marine, versus freshwater, species.

“Even though one of the benefits of listing might be … greater protection and therefore that the fish may recover and then have a new fishery or bigger fishery on it, that is rarely captured in the cost-benefit analysis,” Reynolds says. “The result is that the cost-benefit analysis makes it look like it’s going to be pretty expensive [for government] to list them.” The committee doesn’t take cost-benefit analysis into consideration in its independent decisions, which strictly examine the threat status of species.

Taylor says the problem also relates back to Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s contradictory oversight responsibilities.

“[Fisheries and Oceans] is full of good people. They have good intentions. I just think it really goes to this idea of a conflicted mandate,” Taylor says. “It’s the Ministry of Fisheries and Oceans. It’s not the Ministry of Fish Conservation and Ocean Conservation. So historically, the entire ministry has been set up as a unit to promote fisheries.”

That conflicted mandate is well established in scientific circles. In 2012 and again in 2019, the Royal Society of Canada, which represents distinguished Canadian scholars, scientists and artists, called for a devolution of “ministerial discretion” powers within the federal Fisheries Department, which allow ministers to make decisions that run counter to sustainability and conservation measures.

In its 2019 statement, the society stated “the current pace of statutory and policy implementation by [the Department of Fisheries and Oceans] is impeding Canada’s efforts to fulfill national and international obligations to sustain marine biodiversity, a deficiency increasingly magnified by the pressing need to adapt to and mitigate climate change.”

One way to address the tension between conservation efforts and commercial interests, Taylor believes, would be for Environment and Climate Change Canada to take the lead on deciding which aquatic species to list on the species at risk registry. While the Environment Ministry is officially responsible for species at risk, Taylor says, in his experience, the department “has basically punted the treatment of marine fishes and freshwater fishes to the Department of Fisheries and Oceans.”

“Why is it that [Environment and Climate Change Canada] is able to design recovery strategies for everything from a lichen to a polar bear? But for some reason, they’re not able to do it for fish? The bottom line is we’ve never given the Species At Risk Act a chance,” Taylor says.

In an emailed statement to The Narwhal, communications director Lemkay didn’t directly respond to a list of detailed questions. “The Species At Risk Act is one [of] several legislative and other tools [Fisheries and Oceans Canada] uses to protect aquatic species at risk,” Lemkay wrote. “Protections for aquatic species are also provided through the Fisheries Act, the Oceans Act, the Canada National Parks Act, as well as a number of provincial, territorial and municipal legislative tools and other non-legislative tools.”

“There is a robust legal and regulatory framework for aquatic species at risk which offers protection to all aquatic species. [Fisheries and Oceans Canada] will continue to protect aquatic species, using all the tools available, including the Species At Risk Act and the Fisheries Act,” Lemkay wrote.

In 2019, revisions to the federal Fisheries Act legally obliged Fisheries and Oceans Canada to restore the health of prescribed fish stocks. The department has already added 30 fish species, including Atlantic cod and Atlantic mackerel.

Oceana Canada, the world’s largest ocean-based charity, just released its 2022 fishery audit, which found fewer than one-third of wild fish stocks in Canada are considered healthy, and the vast majority of critically depleted stocks lack rebuilding plans. Now, Fisheries and Oceans Canada is considering adding a second batch of 62 fish stocks to the fish stocks provision of the Fisheries Act, which would require the ministry to develop rebuilding plans while also taking necessary measures — from quota cuts to fishing gear restrictions to fishery closures — to restore the health of those fisheries to sustainable levels. Public consultation is open until mid-December.

It’s a good idea in theory, independent scientists say, but in practice, they’ve criticized the plans as focused more on fishing plans than plans. At the end of 2020, Fisheries and Oceans Canada released its first-ever rebuilding plan for northern cod. At the time, The Narwhal reported independent scientists, conservationists and Indigenous communities said the plan failed to address the root causes that continue to keep cod well below its historical level of abundance.

“Fishes comprise the largest group of wild, undomesticated organisms that humans regularly consume as food,” Hutchings, the late renowned fisheries biologist, wrote in his 2021 book, A Primer of Life Histories.

But that appetite is increasingly hard to feed. Changes in land and sea use, climate change, pollution and invasive species are the top reasons for biodiversity loss and extinction today. According to a 2019 United Nations report, one million species are threatened with extinction globally, many within decades and more than ever before in human history.

When it comes to fish, overfishing is a primary threat. That threat is even greater for marine fishes than it is for their freshwater counterparts. In 2019, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization estimated 35 percent of global marine fish stocks are harvested at biologically unsustainable levels. In Canada, Oceana Canada estimates nearly one in five wild fish stocks are critically depleted — and yet continue to be fished.

Fish species considered at risk are on the rise in Canada. But despite this, fewer than half garner the recognition or protections recommended by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife.

Even though the number of fish species at risk is increasing, less than half of the 209 fish species the committee has classified at risk were subsequently listed under the Species At Risk Act. In other words, the committee has assessed 2.5 times as many fish species as at risk as Canada’s Environment Ministry has chosen to use its strongest powers to protect.

Salmon species considered iconic to both Indigenous and settler communities are among the fish yet to receive the federal government’s full protection. Along with the 48 Pacific salmon species it has recommended for species at risk listing, the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada has repeatedly recommended 10 species of Atlantic salmon be listed as well. On both coasts, the federal government has listed only four — total.

Some of the committee’s recommendations for salmon are more than a decade old: in 2010, it recommended listing a half-dozen Atlantic salmon populations for which the federal government has yet to make a decision.

This 12-year delay comes in spite of a more recent commitment to speeding up the process. In 2017, former environment and climate change minister Catherine McKenna announced a 24-month timeline for species at risk listing decisions for terrestrial species and some aquatic species, with a 36-month timeline for “more complex aquatic species such as actively fished species.”

According to October’s auditor general report, Fisheries and Oceans Canada is not meeting these expectations.

“We found that it took an average of 3.6 years to complete the listing process. Some advice took much longer,” the auditor general’s report said. It also found “the listing decision process should have been completed for 44 species at risk within the required time frame, but it was completed for only five species.”

Currently, 10 of 15 distinct wild Atlantic salmon populations in Canada have been deemed endangered, threatened or of special concern by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. And while the Government of Canada told stakeholders in the fall of 2020 that it was in the process of reviewing overdue listing decisions on Atlantic salmon, it hasn’t made a decision for even one population of the fish in that time.

There is one decision, total, on Atlantic salmon populations: the inner Bay of Fundy (New Brunswick) salmon population was listed as endangered back in 2003. In 2010, another population, the Lake Ontario population, was noted on the list as extinct: since then, the committee recommended four more Atlantic salmon populations receive federal protections.

Atlantic salmon were scheduled to be assessed by the committee this month, which could mean new recommendations to the government by September 2023. The government’s own timeline suggests any decisions about adding species to the protection registry wouldn’t be made until 2024 at the earliest or by 2026 at the latest.

Wild Atlantic salmon aren’t fished commercially anymore: it’s primarily a farmed species in Canada. Open-net or ocean-based aquaculture continues to expand on Canada’s East Coast: this creates jobs in rural communities, but comes at a time when such facilities are being shuttered on the West Coast because of concerns around open-net fish farms as breeding grounds for parasites, viruses and bacteria that can devastate wild populations.

“How can [Fisheries and Oceans Canada] do both — protect and promote wild fisheries?” asks Ross Hinks, director of natural resources for Miawpukek Mi’kamawey Mawi’omi, a Mi’kmaq First Nation in southern Newfoundland. Hinks is Mi’kmaw from Conne River, on the south coast of Newfoundland and Labrador, and also believes the fisheries management model in Canada is flawed.

The mighty Conne is the river from which this First Nation derives its name — Miawpukek means “middle river place.” At one time, the river saw over 10,000 salmon run annually. In 2020, there were just 119, or one per cent of that figure.

Many of the salmon now in Conne River are likely escaped farmed fish, says Hinks, who worries about the future of wild salmon in an area that has the most densely populated open-net pen aquaculture in the country. He has been calling on the federal Fisheries Department to put protection measures in place for Conne River Atlantic salmon, and blames government inaction on prioritizing commercial interests ahead of conservation efforts.

On the Pacific coast, the lack of species at risk status for wild Pacific salmon populations is significant evidence of the lack of protections for species prized by commercial interests. The wild Pacific salmon fishery is highly lucrative, hauling in over $22 million in 2020, the most recent year for which Fisheries and Oceans figures are available. And that figure is a fraction of historical profits.

The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada has told the federal government 43 Pacific salmon populations are at risk: 22 Chinook, one coho and 20 sockeye. Trout are part of the same genus and family and the committee has also designated five at-risk populations of trout: one rainbow, two steelhead and two westslope cutthroat trout.

Of the four salmon or trout populations currently included on the federal endangered species list, none are considered commercially valuable.

The lack of effective protection has been problematic in British Columbia, where declining salmon populations have devastated many local economies and Indigenous communities. In its recent fishery audit, Oceana Canada reported for the first time on the degree to which fisheries management plans incorporate Traditional Knowledge, which is now required under the Fisheries Act.

“Indigenous knowledge systems and ways of knowing should be incorporated into fisheries management by being considered on an equal footing with [Fisheries and Oceans Canada] science contributions and with opportunities for separate Indigenous-led assessments,” the audit stated.

Barnes, of Kispiox First Nation, says he’s discouraged by Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s management of Pacific salmon in B.C. While overall sockeye numbers have remained around the same as they were a century ago, the diversity of wild sockeye in the region has declined by an average 70 per cent in the Skeena River.

“We need to be thinking about what’s best for the fish, not what’s best for our pockets,” Barnes says, adding he believes Fisheries and Oceans Canada often puts ministerial discretion ahead of its own science.

“There’s lots of science, or there appears to be, [and] there’s lots of science effort, but decisions are taken by ministerial discretion,” Barnes tells The Narwhal. “I don’t think anyone would say [Fisheries and Oceans Canada] makes science-based decisions.”

A variety of factors threaten wild salmon: warming waters, habitat degradation, land and water use pressures, overfishing and acute events such as toxic spills and landslides, to name a few. But Barnes says the ultimate failure is rooted in a settler-colonial fisheries management regime, which in Canada is led by the Department of Fisheries and Oceans.

He says the current federally run model is too detached from what matters to those with boots firmly planted in the rivers. Barnes wants to see fisheries decision making decolonized and put in the hands of those with the most at stake.

“There’s no desire or willingness to create the cultural change that is needed in short order to save the fish,” Barnes says. “I’d like to put my finger on an opportunity for reconciliation that shakes things up in how we manage fisheries in this country. I don’t see a path to that yet.”

Wild Pacific salmon look set to mimic the history of Atlantic cod, with governments opting for fishery closures while seemingly avoiding more powerful species-protection measures. This past July marked 30 years since the cod moratorium — a 1992 federal government closure intended to last two years, but still in effect today.

To this day, none of the five Atlantic cod populations — valued at nearly $24 million in 2020 by Fisheries and Oceans — the committee deemed at risk have ever made it onto the species at risk registry.

Updated Jan. 17, 2023, at 3:30 p.m. ET: This article was updated to correct a line that stated “more than half of all fish species or populations assessed as at risk end up listed under the Species At Risk Act.” In fact, it is less than half of all fish species or populations assessed as at risk that end up listed under the Species At Risk Act.

From the air, what stands out is the water. Rivers and streams too numerous to count, winding through a vast expanse of peatlands and forests,...

Continue readingIn this week’s newsletter, reporter Emma McIntosh talks about a trip to far northern Ontario...

Progress on conservation faltered under Manitoba’s previous government. Will the NDP make good on its...

Investigations, photojournalism and other reporting from 2023 have been recognized by the Digital Publishing Awards...