B.C. failing to protect 81% of critical habitat for at-risk species: government docs

B.C. allows industrial logging in critical habitat for at-risk species — part of the reason...

High concentrations of a potentially toxic element have been found in fish in the Kootenai River of Montana and American scientists are pointing the finger at Canadian coal mines for the contamination.

In late September, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency published a report documenting elevated concentrations of selenium in fish just south of the U.S.-Canada border.

The study found some fish contained selenium concentrations surpassing the U.S. recommended maximum levels. Researchers found similar concentrations of selenium in the eggs of mountain whitefish.

“Selenium loads have been increasing over time in the Elk River, British Columbia, Canada, due to coal mining operations and runoff from associate spoil piles,” the report reads.

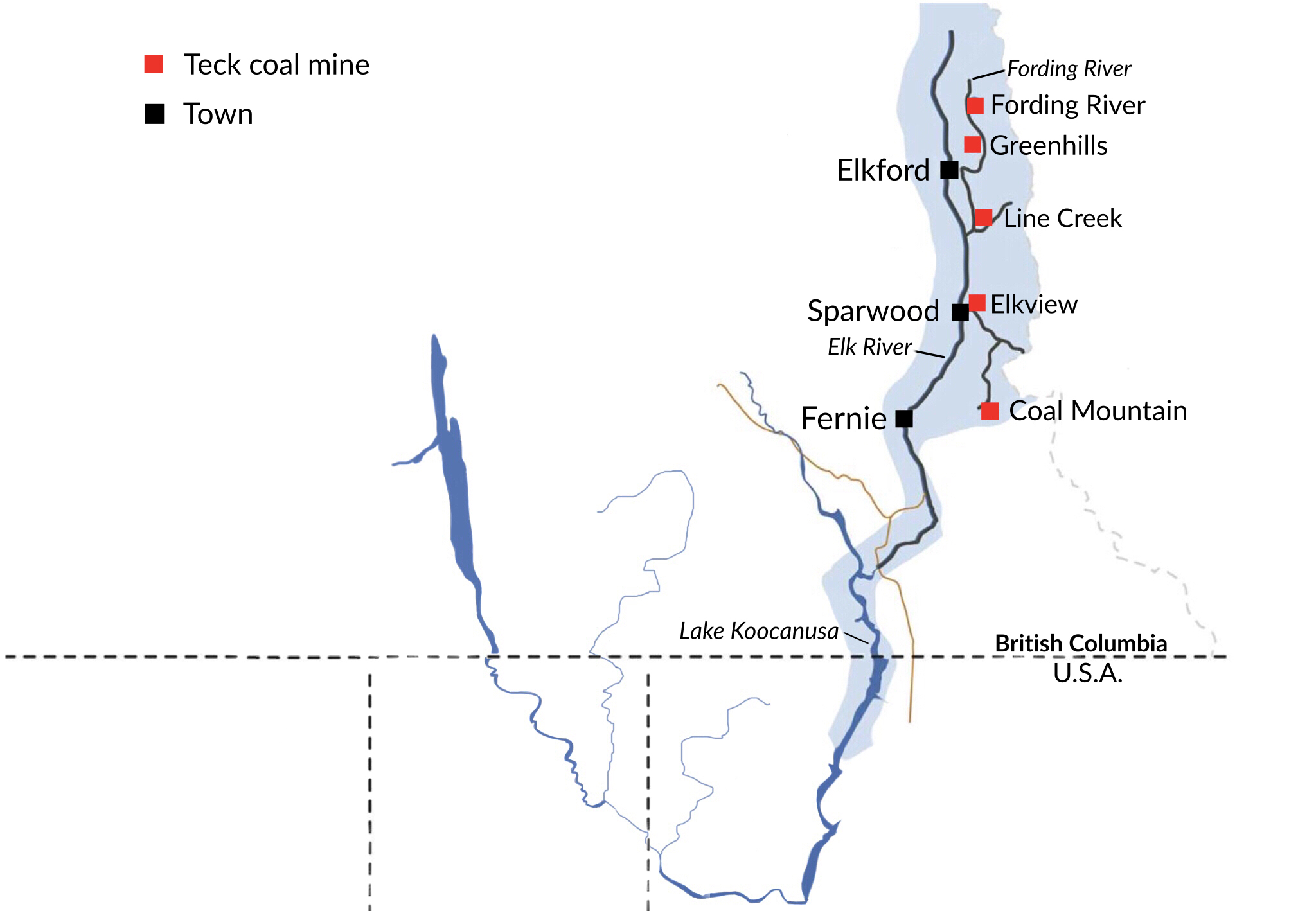

The Elk River is a tributary to the Kootenai River in Montana as well as Lake Koocanusa, where the ongoing research is being conducted. Coal mines in the Elk Valley, near Fernie, B.C., have been singled out as the main source of the contaminant.

Teck’s five metallurgical coal mines are all upstream of the transboundary Koocanusa Reservoir. Map: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

While selenium is an essential element for survival, overexposure can have devastating effects. In fish, it can lead to facial and spinal deformities, or an absence of the plates that overlay and protect the fish’s gills. In humans, it can lead to hair loss, muscle weakness and decreased brain function, among other issues, according to Health Canada.

Meanwhile in Canada, a growing awareness of selenium as a byproduct of mining, paired with numerous unknowns about its impacts in different aquatic environments, led toxicology researcher Stephanie Graves to take a closer look at its impacts.

Graves, a PhD student at the University of Saskatchewan, spent the last two years dumping various doses of selenium into lake enclosures in Ontario to monitor the effects, both at and above the recommended government thresholds.

Stephanie Graves collects samples from her research enclosures. Photo: Emilie Ferguson / Experimental Lakes Area

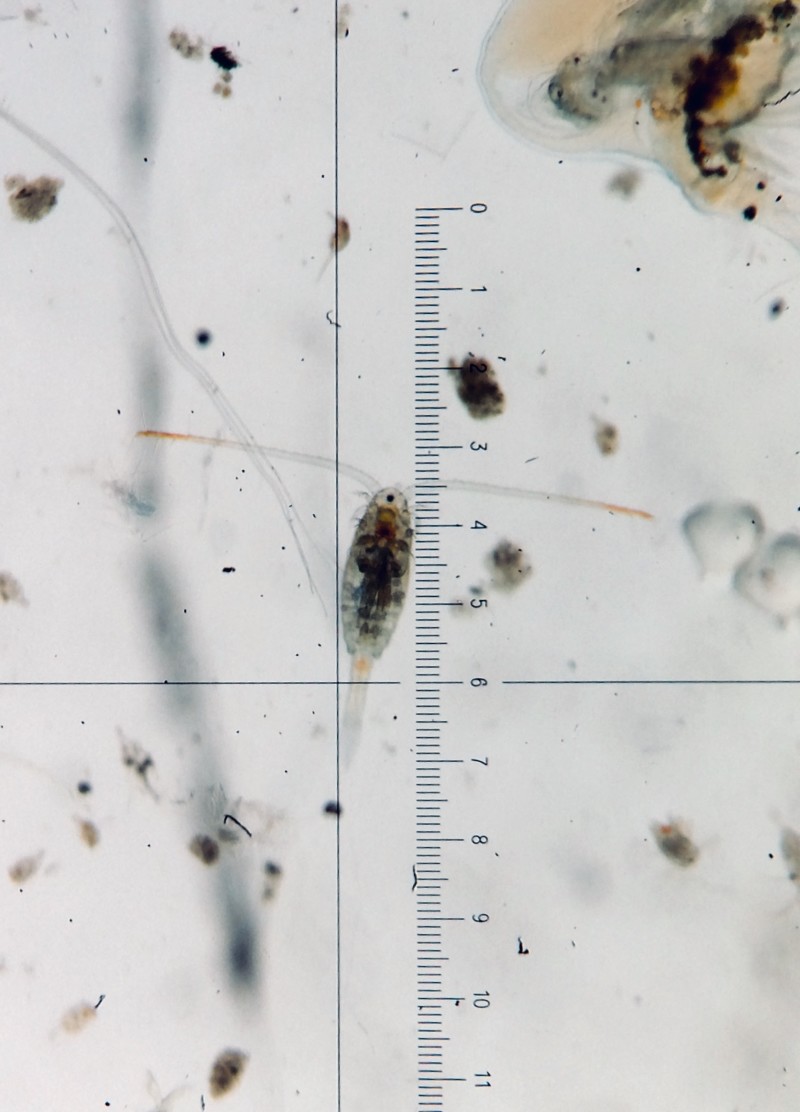

Graves monitored the effects of selenium on a number of species, from fish to invertebrates, such as this copepod. Photo: Stephanie Graves / Experimental Lakes Area

Her research was done in two lakes reserved for such research at northwestern Ontario’s Experimental Lakes Area — a collection of 58 lakes cut off from nearly all human influence, used by researchers to conduct studies free of other contaminants and influencing factors.

Graves wanted to address two things in her research: how much selenium accumulated in invertebrates like zooplankton and other aquatic insects, as well as larger species such as fathead minnows. She also wanted to know what elevated concentrations did to these species.

Tiny invertebrates often don’t receive a lot of attention, but they are an integral piece of the aquatic food web.

“What we found so far is that those organisms can be very sensitive to selenium,” Graves said.

In fact, she found that some of the invertebrates were wiped out, or nearly wiped out at higher concentrations of selenium. Mayflies are often used to demonstrate impacts of pollution, Graves explains, because they are so sensitive — and this was no exception.

“They’re an important food source. So losing [mayflies] could have implications for higher trophic level organisms like fish. And invertebrates in general have very important roles in the ecosystem, in nutrient cycling and the transfer of nutrients to higher trophic levels,” Graves said.

The loss of even some of those organisms is significant, she added.

Grave’s research also found significant losses in a kind of zooplankton — another principal food source for fish.

And if you doubted just how important these seemingly small shifts are, Graves only exposed fish to the selenium-dosed environments for six weeks, and that time was enough to notice decreased growth of the fish.

Even the highest concentrations Graves used in her experiments can be found downstream of mines in Canada, she said. However, her research was very purposefully conducted in a lake, to consider what she calls the “worst case scenario” where those high-concentration flows aren’t diluted before arriving at a low-flow body of water.

“These concentrations aren’t unrealistic,” Graves said.

In one of her papers, published in the journal of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, Graves suggests that recommended federal guidelines for selenium, which is 1 microgram per litre, may not be sufficient to protect all ecosystems — specifically lakes.

In the end, Graves’ research doesn’t bode well for the health of places such as Montana’s Lake Koocanusa.

A group of scientists and conservationists paddle out on to the Koocanusa Reservoir where they are conducting independent water testing. Photo: Jayce Hawkins / The Narwhal

When reached for comment, a spokesperson for the B.C. Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy said that the provincial government is continuously working with partners in Montana to further selenium research.

“The Province of British Columbia is committed to improving water quality in Lake Koocanusa and its tributary river systems,” the statement read.

The B.C. government said that the consortium is working toward setting a new target for the water system that will be followed by both B.C. and Montana regulators starting in 2020.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. Angello Johnson’s shoulders burn, and his arms...

Continue reading

B.C. allows industrial logging in critical habitat for at-risk species — part of the reason...

Lake sturgeon have long been culturally significant and nutritionally important to First Nations in Ontario,...

Mark Carney and the Liberals have won the 2025 election. Here’s what that means for...