Ontario’s public service heads back to the office, meaning more traffic and emissions

For 15 years and counting, my commute from Mississauga to Toronto has been mired by...

If you follow the crystalline waters of the Fording River up the Elk Valley, past Josephine Falls, you’ll discover a small pocket of genetically pure westslope cutthroat trout prized by fly fishers from around the world.

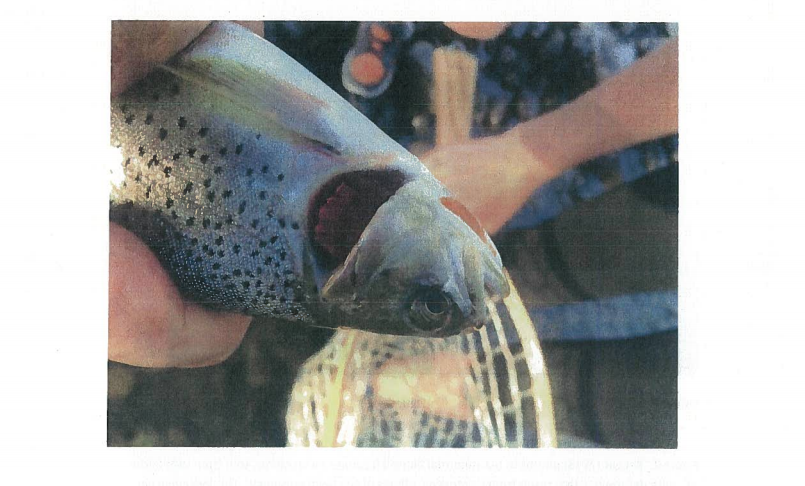

The species is known for sparse, dark freckles that run along the contours of an arched back and the signature orange-pink slits that gouge both sides of its throat. Small teeth line the entirety of its mouth, even under the tongue.

“Cutties,” as they’re affectionately referred to in the bustling fly fishing shops in Fernie, are thought to be one of the first fish species to populate British Columbia after the last ice age. Now found in only in a small fragment of its historic habitat, the species is widely understood to be an indicator of ecosystem health. Pacific populations are currently listed by the federal government as a species of special concern.

The meandering oxbows of the Upper Fording have created the unique conditions for this particular population of westslope cutthroat trout to remain genetically distinct, not having bred or ‘hybridized’ with other nearby populations. Yet these very same gentle waters now threaten to bring an end to this particular lineage of westslope cutthroat trout, first noted in the journals of Lewis and Clark and christened with the scientific name Oncorhynchus clarkii lewisi.

The Upper Fording River, where high levels of selenium have been measured, is closed to fly fishing. The river is the namesake of Teck Resource’s Fording River coal mine. Photo: Jayce Hawkins / The Narwhal

A westslope cutthroat trout caught by Ryland Nelson in the Elk River and is likely not genetically pure. According to Canada’s Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Indigenous species of these trout are critically important to protect as they “may be required for attempts to re-establish extirpated subpopulations, and the future preservation of the species as a whole.” Photo: Jayce Hawkins / The Narwhal

Selenium pollution, leaching from manmade mountains of waste rock, has inundated the waterways of the Elk Valley, depositing itself in the docile currents of the Fording and Elk Rivers.

“We’ve got westslope cutthroat trout and bull trout throughout the lower reaches of the Elk River,” says Lars Sander-Green, an analyst with the local conservation group Wildsight. “The fish are basically concentrating that selenium both in their tissues but, more importantly, in their eggs and in their ovaries that will cause birth defects and reproductive failures.”

Standing beside a snowy bend in the Upper Fording River, Sander-Green explains how selenium builds throughout the food chain. First, it settles in slow moving waters where it is converted into organic compounds by bacteria. It is then taken up by algae which are eaten by bugs which, in turn, are eaten by fish.

“The main concerns people have with selenium are mostly about the fish,” says the unassuming, soft-spoken analyst with a degree in physics and a penchant for data sets.

As the contaminant accumulates in trout it can lead to ghastly facial and spinal deformities, an absence of the plates that overlay and protect the fish’s fleshy gills and — where deformities make survival impossible — death.

In 2014 an expert report prepared for Environment Canada warned that selenium pollution from mining in the Elk Valley was negatively impacting fish. The report warned that increases in selenium pollution would inevitably lead to “a total population collapse of sensitive species like the westslope cutthroat trout.”

In these 1980 photos, Dr. Lemly, an expert asked to prepare a report on selenium pollution in the Elk Valley for Environment Canada, details spinal deformities of mosquitofish (left) and a red-horse minnow (right) as a result of selenium poisoning in North Carolina from a coal-fired power plant. Photo: A. D. Lemly / Environment Canada

A westslope cutthroat trout with a missing gill plate, a telltale deformity caused by selenium poisoning. This trout was caught in 2014 in Coal Creek, a tributary of the Elk River. Photo: Environment Canada

Waste rock deposits cover a massive section of land at the Fording River coal mine. Photo: Jayce Hawkins / The Narwhal

A waste rock dump spans kilometres at a Teck Resource’s mine. Waste rock piles, exposed to the element and growing every day, are what release selenium into the local environment. Rain and melted snow will carry the contaminant into nearby creeks and rivers. Photo: Jayce Hawkins / The Narwhal

Selenium is often found in coal rich deposits like those underlying much of the Elk Valley, where Teck Resources owns and operates five sprawling metallurgical coal mines. To get at those blackened seams, Teck employs a technique known as cross-valley fill, a bucolic euphemism for mountaintop removal mining.

The mines, easily visible in satellite imagery, are staggering in their scope. Mountains are cut down and blasted into terraced slopes that are slowly separated into piles: marketable coal and spoil. Anything not deemed to be of commercial value is trucked by heavy hauler out to piles that eventually grow into jagged black pyramids — manufactured shapes that do a poor job of mimicking the former mountainsides.

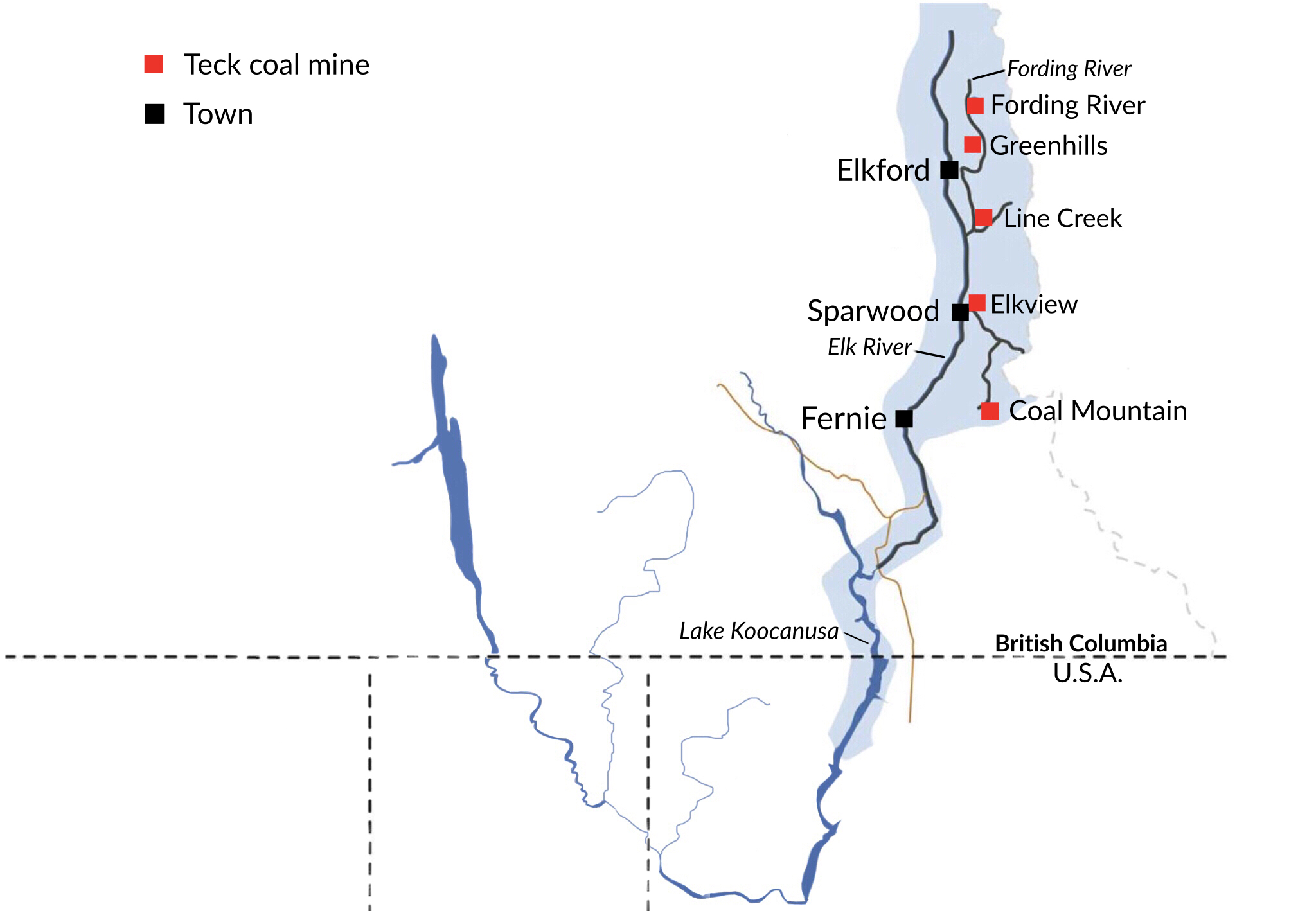

Teck Resources is the world’s second-largest exporter of coal for use in steelmaking, with much of the resource making its way by train to the Westshore Terminals beside the familiar docks of the Tsawwassen ferry. Teck’s Elk Valley mines are some of the largest in Canada — and are poised to expand, despite rising concerns about their growing impact on fish and drinking water.

Westshore Terminals is the largest export facility for coal on the west coast of North America. Westshore ships 19 million tonnes of metallurgical coal each year for Teck. Photo: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

“With this kind of coal mining, open pit or mountaintop removal, there’s a lot of rock between the mountain and the coal,” says Sander-Green, hands tucked into his pockets and shoulders slightly gathered about his neck in an effort to fend off the unseasonable October cold.

“You blast that and truck it over to the next valley, they fill in the mountain valley with this waste rock…and with coal, often there’s some selenium in the rocks…The water trickles down and slowly leaches selenium out of those rocks. It ends up flowing down into these bigger rivers like the Elk and Fording Rivers all the way down into Lake Koocanusa [a reservoir created by Montana’s Libby Dam].”

Teck’s five metallurgical coal mines are all upstream of the transboundary Koocanusa Reservoir. Graphic: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

The confluence of the Elk and Fording Rivers. Photo: Jayce Hawkins / The Narwhal

The expansive waste rock piles filling in low-lying areas of the Elk Valley are exposed to air and water — the elements necessary to move selenium — all year round. The result is a monumental selenium spill in slow motion.

Selenium is a naturally occurring element and is essential to human health in very small doses but can become toxic at higher levels. It is harmful to aquatic life and other egg-laying creatures, even at low levels.

In order to safeguard aquatic life, B.C.’s water quality guidelines recommend selenium levels not exceed two parts per billion. Those same guidelines limit selenium in drinking water to 10 parts per billion. In the U.S., the Environmental Protection Agency’s guidelines set safe limits for aquatic life at 5 parts per billion.

Measurements taken throughout the Elk Valley have found selenium levels at 50 or 70 parts per billion. In many cases, levels are higher than 100 parts per billion. (A 2013 study found selenium levels in rivers upstream of the mines at 1 part per billion).

Yet the B.C. government continues to sanction the expansion of Teck’s mining operations, despite a failed water treatment experiment by the company and a distressing new problem: the contamination of drinking water.

Private wells on local farms and a municipal well in the district of Sparwood, home to many of the miners working at Teck’s operations, have been taken offline after showing selenium levels higher than 10 parts per billion, well in excess of what is considered safe for human consumption.

Doug Hill, regional director of mining operations with the B.C. Ministry of Environment, says exceeding B.C.’s water quality guidelines for selenium is not enough of a reason to slow down mining activities.

We’re already over our numbers that we want to see,” Hill says in an interview, before issuing a quick reminder: “Our water quality guidelines, they’re not law in and of themselves. They are used as benchmarks to assess the impacts of mining projects on water quality.”

Asked if he anticipates more contaminated sources of drinking water, Hill hesitates.

“I couldn’t say that we’re at a point now with our groundwater monitoring that we could accurately predict that.”

Bill Hanlon, a local horse breeder and conservationist, manages a property just outside of Sparwood that is a popular destination for hunters seeking proximity to game in the Elk Valley, which is class one bighorn sheep winter range. The private well on that property is contaminated.

Hanlon wants to see a better balance between environmental and economic interests in the Elk Valley and argues, despite the problems with selenium, he believes Teck works hard to be a good neighbour and has helped created protected areas to offset the impacts of mining. Photo: Jayce Hawkins / The Narwhal

Bill Hanlon, a local guide and conservationist, is worried too much selenium in the Elk Valley ecosystem may take the river to a “tipping point.” Photo: Jayce Hawkins / The Narwhal

“This property here has some of the highest selenium measurements. They test it regularly,” Hanlon says.

The property is on the opposite side of the river from the coal mines, prompting Hanlon to ask, “…why is the selenium going this far out in the gravel bed river system?”

Hill says Teck conducted a 2017 groundwater study, currently under review, that will be used by the company to create a “conceptual model” for how groundwater flows and moves throughout the valley.

“It’s complicated,” Hill explains. “The geology there isn’t simple to understand. The selenium is going to behave differently in groundwater than in surface water.”

Hanlon, who is also the chair of the British Columbia Backcountry Hunters and Anglers, says he’s worried by proposals for three new coal mines by three new companies in the Elk Valley. “If we lose this river, if it tips…there’s a lot of livelihood based on this area and on the river itself.”

Fernie airbnb manager and fly fisher, Ryland Nelson. “The clear-cut logging that we see on the hillsides, that’s a lot more in people’s face but this selenium issue is, you know, it’s silent and it is much, much bigger of an issue to the health of this watershed,” Nelson told The Narwhal. Photo: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

“It’s not just the coal mines, it’s cumulative effects and I fear we’re getting near a tipping point in terms of a balance of a healthy environment and a healthy economy. We don’t seem to know when to quit.”

University of Montana biologist Erin Sexton began studying selenium in the Elk Valley nearly two decades ago when the wildlife-rich Flathead Valley, next to the Elk Valley, was being eyed by coal companies. Mining and oil and gas development are now permanently banned in the Flathead Valley.

“We came up to the Elk River in B.C. from Montana in the early 2000s to collect data,” Sexton recalls during an interview. “We were surprised by what we found.”

Sexton said she and her colleagues expected the Elk Valley river system to be impacted by mining, but they did not anticipate the extent of the damage they encountered.

“The issue with selenium is that it’s what we call biphasic, meaning that it goes from good-for-you to toxic in a really tiny window,” she says.

Of particular alarm for Sexton was the near absence of macroinvertebrates, the little bugs — mayflies, stoneflies, caddisflies — that feed the local fish populations.

“We’re losing certain species of those very important macroinvertebrates. Ones that are more sensitive to pollution are disappearing and we know they should be here because we found them in the Flathead which is very close,” Sexton says. “Rather than this rich diversity…we found just a few species in the Elk River.”

To the alarm of Montana officials, Lake Koocanusa, fed by the Elk River, is showing signs of increased selenium pollution.

Sexton says selenium contamination is acute directly downstream of the mines. “Whereas further down in the reservoir and in the system, [the effects] are more chronic and will take place in a longer timeframe.” She adds that the overall effects of selenium poisoning can be hard to identify, despite seeing deformities in fish in the Elk.

“It’s kind of a hard problem to detect because the ultimate impact of selenium toxicity is a failure to reproduce so if you’re not seeing those fish in the system, then how do you know that they’re being impacted by selenium?”

In an effort to determine the extent of selenium contamination, one day in October Sexton and colleagues from B.C. and Montana conservation groups hop into a flotilla of canoes, using GPS coordinates to locate the spot in the Koocanusa reservoir where Teck has done water sampling.

Erin Sexton leads a group out on to the Koocanusa Reservoir to conducting independent water testing. Photo: Jayce Hawkins / The Narwhal

Once the canoes are in position, Sexton takes numerous water samples, using standardized methods developed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

“Basically, we’ll send it back to the lab with a duplicate and then see what we get back,” she says.

Teck and the B.C. government conduct regular water testing, but the raw data is not made available to the public. Some areas, like this particular spot on Lake Koocanusa, aren’t tested year round.

The reservoir can freeze and experience a drop in water levels, creating dangerous cavernous conditions under the ice. It’s a barrier to winter water testing, an important time to test for selenium because low water levels can mean a higher concentration of pollutants, says Sexton, who is among a growing chorus of Montana voices expressing concerns about selenium pollution from Teck’s mines crossing the B.C.-Montana border.

Last July, two U.S. representative on the International Joint Commission, a Canada-U.S. body that oversees a treaty to protect transboundary waters from pollution, went public with criticism that their Canadian counterparts were suppressing science on the health impacts of selenium and relying on out-of-date data rather than on more current studies for an upcoming commission report. The commissioners warned that Teck may not even have the technology necessary to stem the tide of selenium moving from the Elk Valley mines into U.S. waters.

Michael Jamison, senior program manager with the National Parks Conservation Association in Montana, worries that contamination flows directly south, where he lives with his family. What’s happening downstream is bad enough, says Jamison, “but then when you look upstream at what’s happening in B.C. — polluted air, contaminated fish, and wildlife — I don’t know how they handle it…it’s so acute on the northern side of the border.”

Jamison is perplexed by the unabated pace of mining in the Elk Valley, despite pollution levels well above B.C.’s guidelines. In the U.S., companies would never be granted new permits if they were found to be in violation of permit levels, he says. There are also other important differences between industrial operations in B.C. and those south of the border, Jamison notes.

“We have an Endangered Species Act in the U.S. that doesn’t really have a counterpoint in B.C. We have enforceable requirements around wastewater discharge and remaining within the parameters of your permit. Those presumably exist here…it seems like in the U.S. we have rules written in ink, maybe up here they’re written in pencil with an eraser handy…’we’ll adjust the permit.’”

Even if Teck’s Elk Valley operations halted immediately, Jamison says the problems they have created will persist for hundreds of years, likely long after the company ceases to exist.

“These piles of waste, they’re going to be leaching selenium into that system for 700, 1,000 years. Teck’s not going to be around in 1,000 years.”

Some of the many waste rock piles that line coal mining operations all throughout the Elk Valley. Photo: Jayce Hawkins / The Narwhal

Hill confirms that Teck’s Elk Valley operations are monitored under a valley-wide permit that has short-, medium- and long-terms selenium targets established under the Elk Valley Water Quality Plan. He agrees that selenium pollution from Teck’s mining operations is a long-term problem.

“These legacy waste rock piles there are going to be leaching sulphates and selenium for years to come, regardless of what happens to the mines right now,” Hill says. “It’s going to take long-term sustained action before we see really remarkable changes to water quality.”

The water quality plan established in 2014 focuses only on attempting to stabilize selenium levels in the water until 2023, Hill explains. B.C. does not anticipate that Teck will begin the work of lowering selenium levels in the watershed until the 2030s.

But just how that will happen isn’t clear. Teck introduced a $600 million water treatment plant in 2014 that proved problematic from the start. The plant caused a fish kill in 2014, six months after coming online. In 2017, the plant was taken offline after it was revealed that the treatment process was releasing a more bioavailable form of selenium into the environment, meaning it was taken up more readily by biotic life.

Teck said in a statement that the struggling water treatment facility at its Line Creek operations has been recommissioned and is now back in operation. A second water treatment facility is currently under construction, Teck spokesperson Chris Stannell wrote in an e-mail to The Narwhal.

Teck expects to invest between $850 and $900 million in water treatment facilities over the next five years and is experimenting with ‘saturated rock fill’ methods in an attempt to reduce the amount of selenium entering the environment via waste rock piles, Stannell says.

Teck Resources, which posted profits of $6.1 billion in 2017, was the single largest donor to the BC Liberal party. The practice of corporate political donations has since been phased out in B.C.

Hill acknowledges there have been significant “setbacks” in Teck’s water treatment plans.

“There’s a lot of different parts and piece to this project and whilst there might be setbacks in one particular area — albeit a really important area, which is the treatment technology — I think we need to continue to plug on and move forward to make this plan work.”

Enbridge Gas will face Waterloo Region in a hearing before the Ontario Energy Board to renew an agreement that would allow the company to continue...

Continue reading

For 15 years and counting, my commute from Mississauga to Toronto has been mired by...

For our last weekly newsletter of the year, we wanted to share some highlights from...

The fossil fuel giant says its agreement to build pipelines without paying for the right...