17 government inspectors, 170 companies and more than 9,000 potential infractions: inside B.C.’s oversight of the oil and gas sector

Notes made by regulator officers during thousands of inspections that were marked in compliance with...

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter.

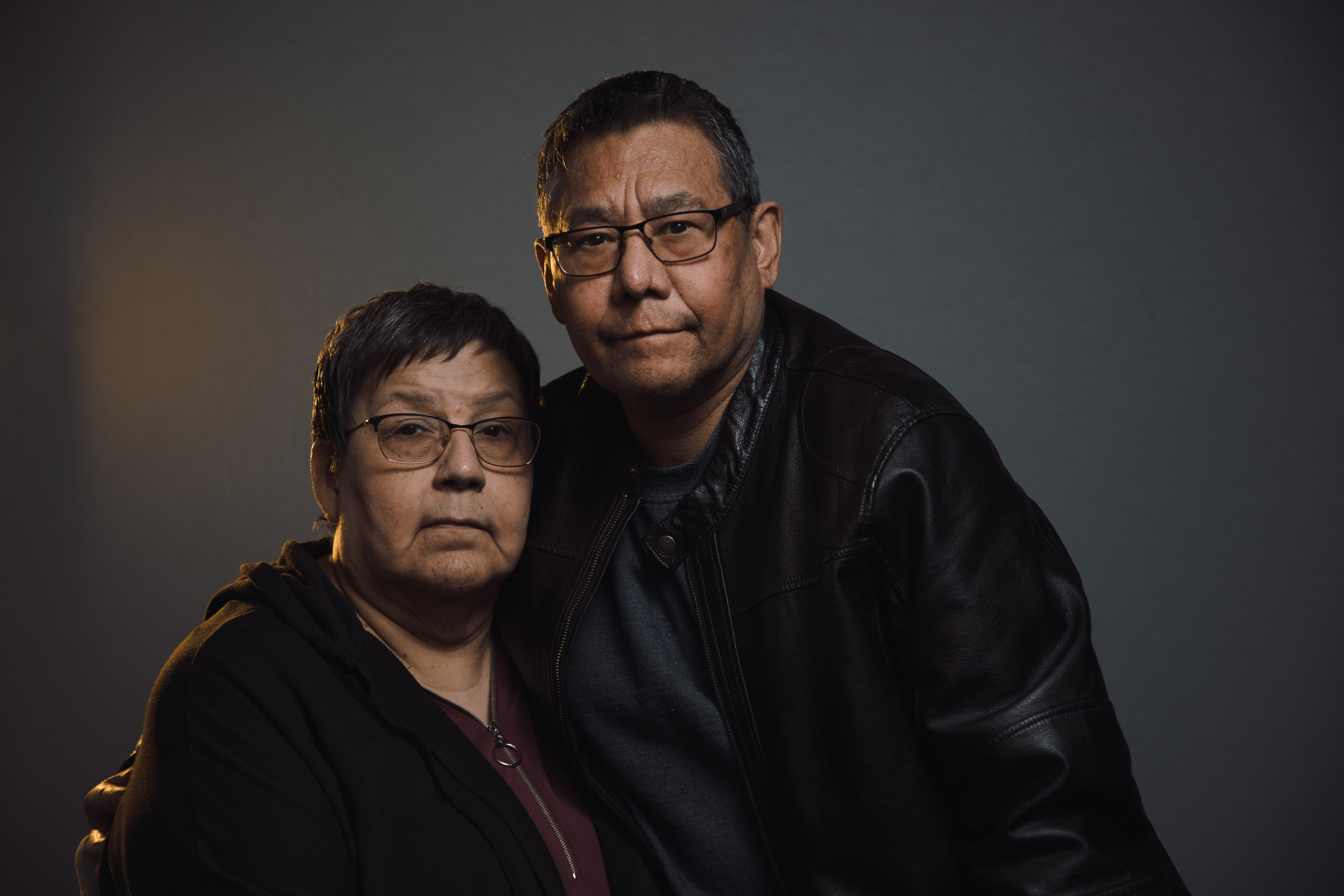

Editor’s note: Before this photo essay was published, Claire Cardinal passed away on Aug. 11, 2024, as a result of her illness. Her husband still wants her story told.

Residents of Fort Chipewyan, Alta., have been worried about their water for decades.

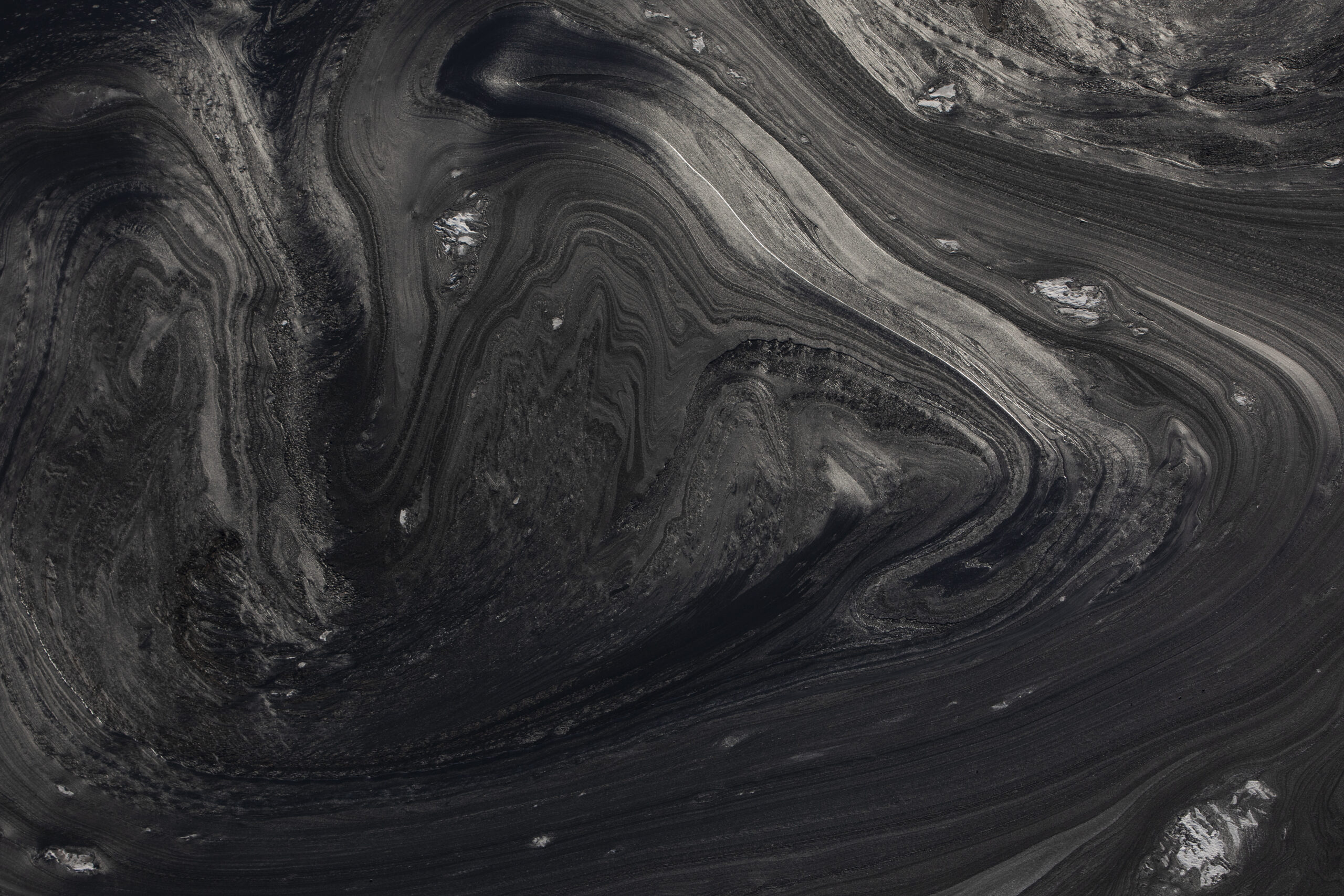

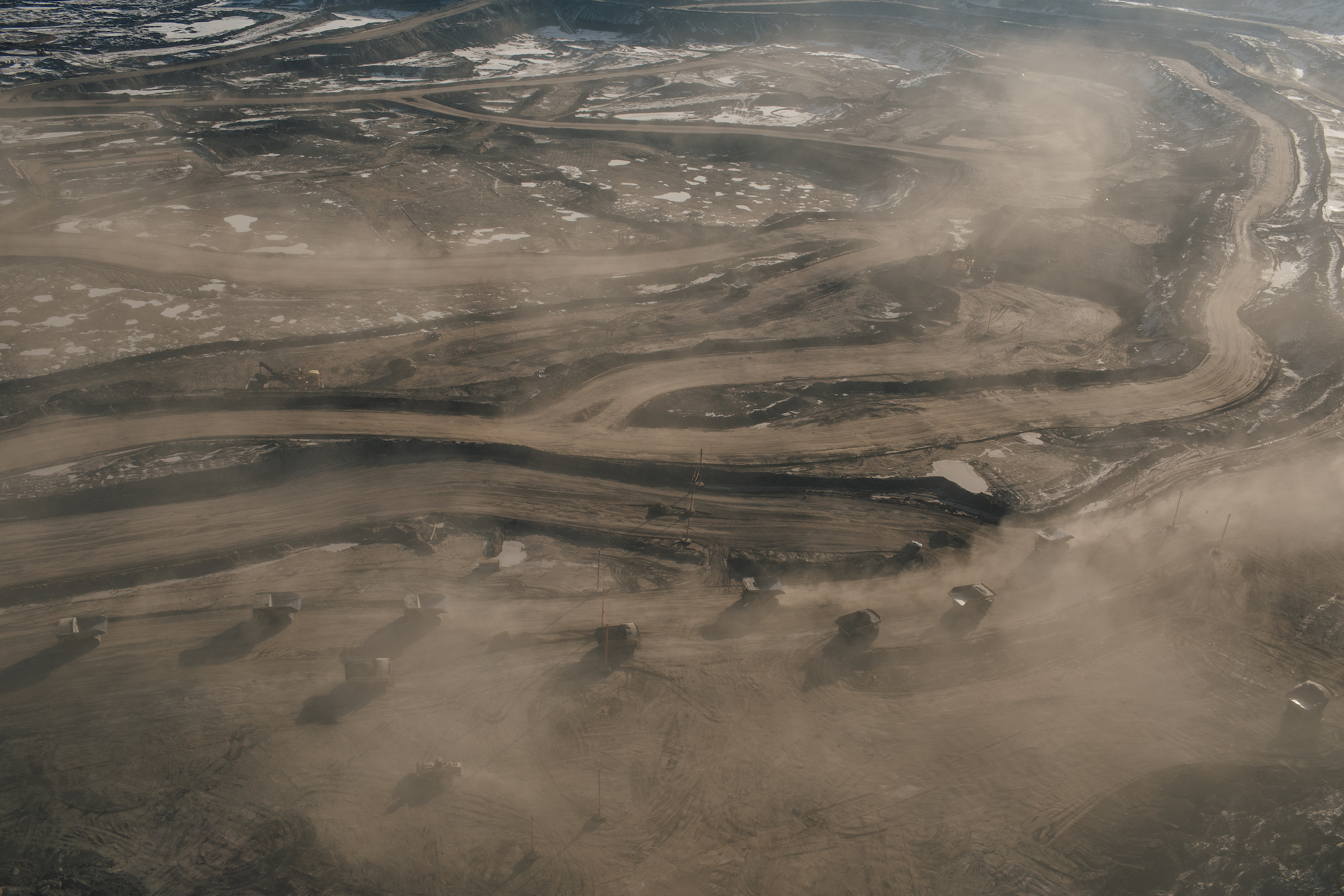

They live downstream from “ponds” of toxic oilsands tailings on the Athabasca River, filled with a trillion litres of byproducts including arsenic, mercury and lead.

There are also naphthenic acids, compounds present in most petroleum sources that are notably corrosive to refinery machinery. Some research has found them to be harmful to the reproductive cycle of certain frogs and fish.

The federal government recently agreed to assess the compounds for toxicity and impacts on human health — an investigation requested by Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation and Mikisew Cree First Nation in Fort Chipewyan.

Drinking water here became world news when Imperial Oil discovered a tailings leak at its Kearl oilsands mine in 2022 — and failed to tell downstream residents for nine months. Meanwhile, the largely Métis, Dene and Cree population continued to hunt, fish, harvest — and drink the water.

Elders are not just worried about water quality, but quantity too. They say oilsands water use and upstream BC Hydro dams, including the Site C dam on the Peace River, have had a major impact on the amount of water available in the Peace-Athabasca Delta. They’ve noticed low water levels and interrupted flood cycles. Not only that: muskrat numbers have dwindled and it’s increasingly difficult to navigate by boat.

But it’s the chemicals in the water that worry them most.

Some people say the water in Fort Chipewyan — known locally as Fort Chip — smells “oily” and they’ve seen fish with lesions and deformities. In 2014, Alberta Health Services concluded “the total number of cancers and most types of cancers in the Fort Chipewyan area were the same as rates in the rest of Alberta.”

Nearly everyone in town knows multiple people fighting cancer, including rare cancers. But despite requests, the federal government has not yet completed a conclusive study of the issue.

While officials monitor the water, and have repeatedly declared it safe, most people who can afford to still choose bottled water instead.

Meanwhile, people are raising families, working, living and dying with unanswered questions about their water. Here, they share their experiences in their own words.

These conversations have been edited for length and clarity.

Kenneth and Claire were married for 15 years. They were both working at Suncor in 2019 when they started to get sick. Kenneth, who has never been a smoker but worked in the oilsands for 27 years, was diagnosed with pulmonary fibrosis and had a double lung transplant. It took Claire a year and a half to get a breast cancer diagnosis — by then it was stage four. In April, after 12 rounds of chemo, her doctors told her there were no more treatment options.

Kenneth Whiteknife: I was on the trapline all my life with my dad in the summer and winter. Hunting in the fall time. Then, when my dad passed away, I just stayed in Chip and I worked in the plant — [the work was] fly in, fly out so I didn’t go out on the trap line.

The money was good there. I was getting paid every Thursday because I was in a union and everything was great. I didn’t think about my health or getting sick or anything like that. But after the last four years I found out I needed new lungs then I realized it: all this money and everything meant nothing.

Everything’s changed now. Money is the root of all evil. Ever since the oil companies and all the money, it’s all changed that now. On the trap-line we never had no iPads or anything. We just lived our own nomadic life trapping every day.

Claire Cardinal: I never heard of cancer. When I was a kid I didn’t know what it was. So when one of my uncles got cancer, in the ’80s, I don’t know what kind of cancer he had, but he died of cancer. That’s how it started. You live in that fear because people are starting to get cancer and it’s kept going and going and going. Now it’s getting worse. People are dying of cancer every year. You hear about it right away — some are lucky some are not.

They have different doctors that come in and out. They gave me a bunch of pills. I have a big bag of pills that I didn’t even take because I knew that wasn’t [vertigo]. I knew deep inside. I knew there was something, I knew there was cancer, but I couldn’t prove it.

[To get treatment] you fly from here with aviation, then you’ve got to jump on the bus, then you go to your appointment and then they send you right back the next day. So you can’t rest, you’re just so tired. Especially when you’re a cancer patient and you’re going to chemo and you can’t stand the smell of anything.

But I’m fighting for my life. And I’m content, I’m just gonna keep doing it. And hopefully I can beat this. I want to be on this earth for another at least 10 years — just to see my grandson when they graduate and the two younger ones. Yeah. Fighting, fighting, fighting.

I’m really angry with the water because I grew up in Fort Chip. I knew how beautiful our water was and how blue it was. Now I look at it — it’s all black and brown and you can’t even see the fish in the lake anymore. We used to see all that so it just hurts me. As soon as I hear somebody has cancer I just cry because I know what they have to go through.

A cook at a Mikisew Cree First Nation work camp, Jennell moved back to Fort Chipewyan with her kids in 2021 after 14 years away. They live on the nearest Cree reserve, a community that deals with intermittent boil water advisories.

I have a three-year-old. I want to live till I’m old because of that. But I also want to make sure that her home in Fort Chip stays safe to live in.

The town’s really divided. Half the town says there’s nothing wrong with the water and the other half says there is. And I’m just kinda like, “we die, we die.” I don’t know what else to say about that.

There were three boiling water advisories before we noticed and we were drinking the water and we were perfectly fine.

Maybe I should have been taking it seriously. Like, am I gonna get cancer in the long run? Are my kids gonna get cancer? Are we gonna get sick from something? Yeah, we might not be taken seriously now, but is it gonna come back and bite us? Me and my kids?

For one example, no one was told anything about [the tailings pond leak]. And we were just drinking the water right there. That is an example of me thinking the water was okay when it really wasn’t and that’s where my trust issues come into play.

I almost feel like the only thing that defines Fort Chip is murdered and missing women and dirty water, like, that’s how I feel. But we have so much more good going on here. I think that we have great leadership here. I’m really proud of the three nations and how they’re working together and our high school and the amount of high school graduates they have here.

All these educated people, and we still got dirty water.

Is it toxic? Is it not toxic? Is it safe to drink? Is it not safe to drink? And who do we believe at the end of the day?

Jason came back to Fort Chipewyan as a young adult after spending time in foster homes. He worked in oil, then left that job to become a hunter, fisherman and carpenter in community housing.

Me and my wife started working full time. And then we rarely saw each other. We were giving all our time to this money for this big vacation, that we didn’t realize that we were spending so much hours being gone from our family.

I was 22 years old, making $100,000 salary a year, like I’m just a young guy.

That was my way of being a father — buying stuff for my children — and I realized after so long it’s not a life I wanted.

I wanted to teach my children how to become self-sustaining on your own land.

I had to relearn my heritage, again, that I had to get taught from my family members and cousins. And it was a real challenge. But I stuck with it. And I got good at it. And I learned to teach others.

When I go to the land, it’s like, everything stops, the noise. The hustle and bustle of working in Fort Chipewyan and in modern society, when you’re out there, everything just kind of fades away.

[After the tailings spill] I was doing a community hunt for ducks and geese. We were doing a good deed to try to feed the community, Elders and people who can’t hunt. And here I am harvesting all these birds that have been tainted and all these fish that have been tainted. And for me, it makes me feel like I just fed somebody something that you wouldn’t feed your dog. And it kind of makes me feel like I shouldn’t be hunting anymore. I don’t want to harvest fish and I don’t want to harvest ducks. And then that boils down to I’m gonna lose my heritage.

I feel like I just want to grow my children up here, and then maybe move to another place, which is kind of sad, because I made a decision to move back home. And now I’m leaving again. Not literally, but it’s in my mind. Like, do I want to be another statistic of that cancer? Do I want to pass away at 65 or 70 years old from a rare cancer?

I do love the community, I do love the vibrant connection to the land and the people, the brothership, the way we come together.

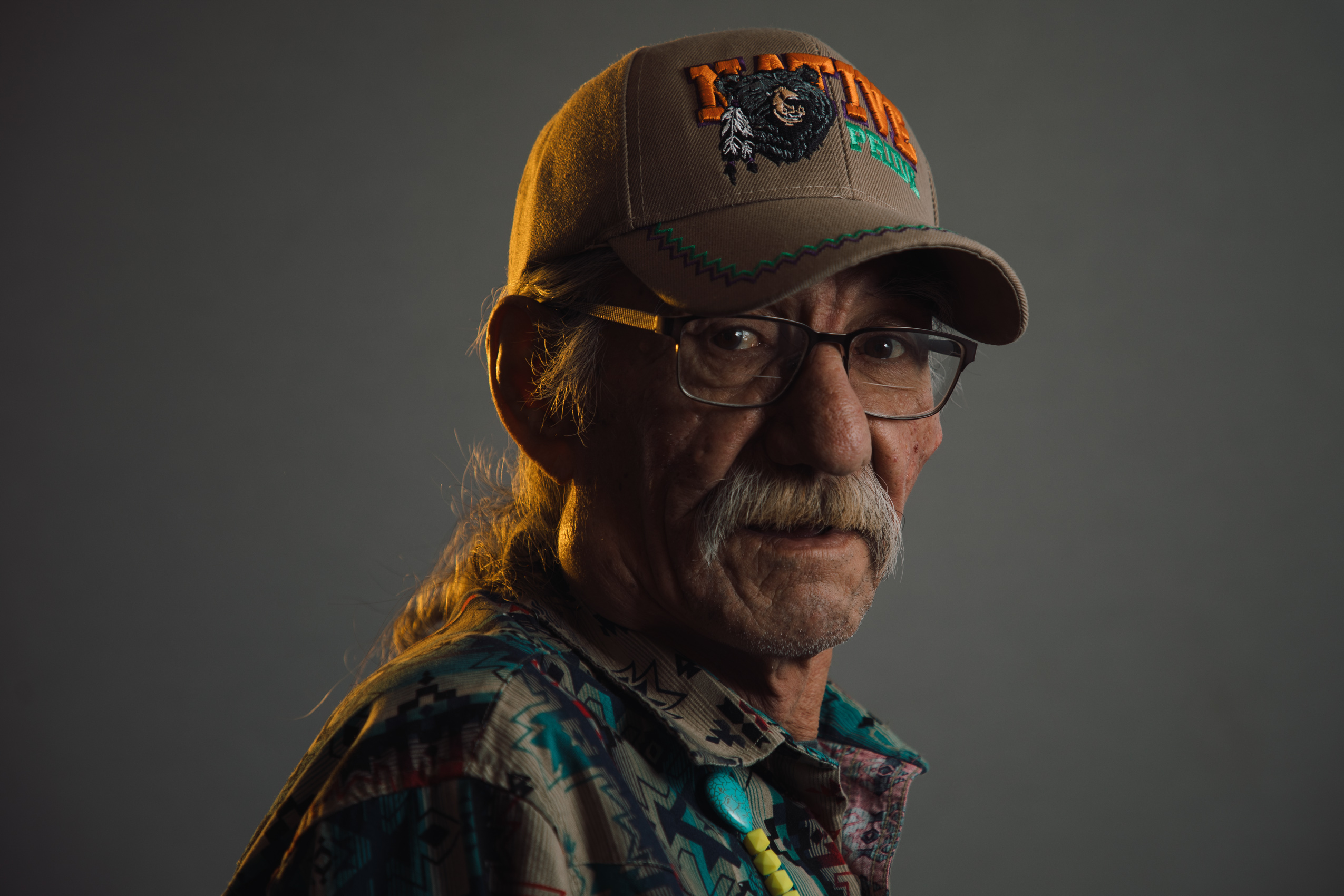

Working on a project to record Elders’ stories, Lionel learned how much the land and water had changed in a short time. Since then, he has spoken in London, Paris, Amsterdam and Brussels advocating for clean water for the people in his community.

They assure us the water is clean, our tap water is clean, but a lot of our people won’t take chances with the tap water. So we have got to buy water.

The Alberta Energy Regulator came into town, they brought up a case of water for themselves. So it’s kind of funny, like, somebody took a picture of him at the airport, you know, the guy’s walking with a big case of water, you know, somebody asked him, “What is that for?” They said, “To drink.” So obviously, they don’t even trust our water. But their job is to protect our water and to protect our lives.

The Alberta Energy Regulator should have strongly enforced these regulations years ago, to prevent this from happening. But it happened twice. And they tried to cover up and they tried to, you know, sweep it under the rug. But they can’t do that. Because like I said, it’s so noticeable. Our people have lived here for thousands of years, we know that something’s wrong.

But first and foremost, is a grief. Because there’s a lot of people in that graveyard that shouldn’t be there.

That’s where the anger comes. Because they know damn well that water is unsafe.

Jean lives in Fort McKay but her cabin — inherited from her mother — is only 13 kilometres from Imperial Oil’s Kearl oilsands mine — and she says she was never formally notified about the leak. At a community meeting with Imperial Oil representatives, she tried to express her concerns personally to a company representative but says he was walking out and didn’t seem to listen.

Alberta Energy Regulator officials are not doing their jobs. They don’t have any answers, all they have is lies, lies and cover up lies, more lies. That’s all they’re about. The government is all lies.

I remember the last time they blew me off and I’m like, they’re not going to blow me off this time.

I want to see them go to court. And I want to see them answer to all the stuff that happened. All those secrets that they kept from us and all that.

I don’t see real actions. [Industry is] still going full bore ahead with all their plans.

I live right beside the water. It’s good to look at, but then, really, when you go to try to consume it, is it doing harm to you?

Even when I go out [on the land] I have to think about water. I go out berry picking and I have to bring water, because of what happened over there at Imperial.

I have faith in my ancestors from their perseverance from long ago, which is why we’re still here. I have to go out there and remind myself all the time to keep connected to them, like at my mom’s trapline. Her spirit is over there, where she roamed and walked and we did stuff together and travelled and hunted — those connections give me a feeling that my ancestors are with me, watching out and looking out for us.

So I keep going. I keep returning to those places that keep me connected, to my ancestors, to my roots. From that I feel good to carry on. To protect those areas for my future great grandchildren.

Roy has hunted, fished and harvested medicines his entire life and says he’d rather be out on the land than to go anywhere else in the world.

[As a child] my job was to get in a three-pound pail. My granny had a five- or 20-pound pail, morning and evening. That’s every day. Didn’t matter if it was -30 C, -40 C below, you had to do that. I used to just go down a creek bed there and punch a hole in the ice. And when you looked at the ice it was crystal dark blue. No contaminants in that water, that’s how pure the water was.

I love the way of life.

When you go and connect with the Earth out there on the land, when you live there long enough, when you observe, when you live most of your entire being out in the land, Mother Earth is the sole teacher of all teachers, not technical equipment.

I’ve never seen the water level this low — where in God’s name are they going to be getting water from, moving on to the future? Even to a point now you can’t even go anywhere along the lakeshore here without having issues and navigational hazards.

Where’s all the [muskrats?] Why all the rats have disappeared?

Now where’s the buffalo? The delta and the park are all drying up.

The wild abundance of wildlife that used to be around here, it’s all disappearing now. The movement of mankind was pushed way way too fast in all places up in the north zone here. And that’s got to be controlled.

You can’t be doing this, it’s man-made self-destruction.

Our young people, they need to have [tradition] and we need to guide them along. Today’s technology, that’s fine. But they have to remember who they are, and where they are because the last resource is going to be the land itself, and the watershed and the fresh water and whatever is left of wildlife north of Fort McMurray.

I don’t look at it as a hope, it is there to happen, and it can be made to happen. That’s why I keep reminding people, I don’t care who it is, never give up. Never give up.

Nothing is ever, ever, ever too late until after the fact.