B.C. failing to protect 81% of critical habitat for at-risk species: government docs

B.C. allows industrial logging in critical habitat for at-risk species — part of the reason...

Ontario Premier Doug Ford believes his road to re-election in 2022 is a highway.

“While the Liberals and NDP constantly fight our infrastructure projects that reduce gridlock and get Ontarians to where they need to be, we are the party that gets things built,” read an email blast sent out Oct. 13 by Ford’s Progressive Conservatives.

But over the past year, Ford’s two major highway projects — Highway 413 and the Bradford Bypass — have come under increasing scrutiny amid concerns about their environmental impact and who could benefit if they’re built. Both are old proposals that the Progressive Conservatives revived and fast-tracked: previous governments had shelved them in the 2000s as a growing body of evidence began to show that new roads don’t actually reduce traffic congestion.

The tension came to a head last week. On the heels of a Torstar/National Observer investigation showing that the Ford government is seeking to re-route the Bradford Bypass around a golf course co-owned by the father of a Progressive Conservative MPP, the province announced that for the first time, it had earmarked funding to advance Highway 413 and the bypass.

“We are ready to build bigger,” Finance Minister Peter Bethlenfalvy said.

Critics were swift to condemn the move: “The premier thinks the road to recovery from COVID-19 is paving over paradise,” Ontario Green Party leader Mike Schreiner said.

Here’s what you need to know about Ford’s highway plans and the controversy swirling around them.

The controversy over Ford’s highway plans is rooted in a deep divide over how best to fix the Greater Toronto’s Area’s congested road system. On average, drivers lose 142 hours — or about six days — to traffic jams annually, a report found in early 2020.

For a long time, governments, particularly in North America, sought to unclog roads by building more routes. Over the last few decades, however, studies have shown that more roads simply attract more drivers, instead of solving the problem. This is called “induced demand:” soon enough, the new lanes tend to become just as congested as the old ones.

In population-dense southern Ontario, gridlock is forecast to worsen over the coming decades as more people move to the region. The Ford government says it believes highways are the best way to fix that — and by focusing on the issue ahead of the election, it’s betting that voters who rely on cars to get around will agree.

“Congestion is a real problem, and members of the opposition just want to keep their heads in the sand and not recognize this reality that plagues people — drivers, commuters, families, workers, farmers,” Ford’s Transportation Minister, Caroline Mulroney, said at Queen’s Park on Nov. 2.

“It’s been a problem for decades. It’s a problem today. As Ontario welcomes millions of new people every five years, the problem is only going to get worse.”

But the Greater Toronto Area’s transportation woes are going to be a lot more complex to solve, said Victor Doyle, a former provincial planner. Studies he saw during his time working for the government show that it would be impossible to build enough lanes to actually accommodate demand for car-based travel in the next 30 years, and that’s not accounting for highway-induced demand.

“Thinking that these two little fragments of highway are going to solve our congestion problems in a rapidly growing city region of 10 million people is just a joke,” he said.

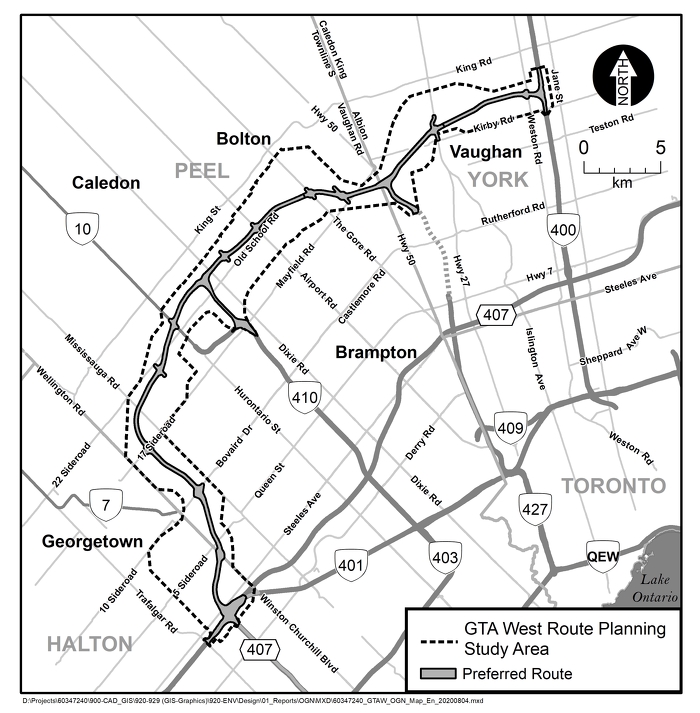

The Ford government’s first major highway project is the 413. It was first sketched out decades ago as part of an expressway that would ring from the Niagara region to the Toronto suburb of Vaughan. More recently, the 60-km route — also called the GTA West Corridor — would connect Vaughan with Milton, to the west. The PCs put it back on the table in late 2018.

Months earlier, the previous Liberal government had shelved the project, which has a price tag between $6 billion and $10 billion, after an independent panel concluded it would save drivers less than a minute daily. (The Ford government argues it would actually save them half an hour.)

Another concern was the 413’s environmental impact: the highway would cross the Greenbelt, a zone of protected land ringing around the Greater Toronto Area. Its route would harm 2,000 acres of farmland, cut through 85 waterways, damage 220 wetlands and disrupt the habitats of 10 species-at-risk.

At the time, there was a lot of talk about how the government should better protect the Greenbelt, increase access to public transit and reduce greenhouse gas emissions, Doyle said. “Highways just weren’t the answer to our congestion problems,” he said.

The year after the PCs revived the idea, they promised to “streamline” the environmental assessment for Highway 413, which would allow the province to allow work on bridges and other early construction to begin before the review is completed. In 2020, they also passed a bill to water down Ontario’s environmental assessment regime overall.

Grassroots opposition to the 413 started to simmer over the winter. By the spring, it had hit a boiling point. Under pressure from residents, a flurry of municipalities along the route — and even some local conservatives — pulled their support for the 413. In April, an investigation by Torstar and National Observer found eight powerful developers, many of them prolific PC donors, owned over 3,300 acres of land near the highway’s proposed path, which could skyrocket in value if the highway was built. Some of the developers had hired lobbyists with ties to the PCs, including Mulroney’s former campaign chair.

In the meantime, environmentalists had asked the federal government to step in and assess the 413 and the Bradford Bypass, a 16-km connection between Highways 400 and 404. The federal environment minister at the time, Jonathan Wilkinson, announced in May that Ottawa would intervene on the 413, citing concerns whether the provincial process would address environmental concerns. The process is more rigorous than what the Ontario government had planned, and could delay the highway for months or possibly years.

The provincial NDP, Liberals and Greens have all called for Highway 413 to be axed — again. All the while, Ford has maintained that the project will go ahead. “It’s going to save a tremendous amount of time,” he said at Queen’s Park in October 2021.

Highway 413 continued to generate backlash in the weeks leading up to the 2022 Ontario election. On April 18, The Star reported that the government’s chosen route for Highway 413 would cut through the protected Nashville Conservation Reserve, avoiding a future development project. The province made the decision in 2020 against the advice of consultants who warned that path would maximize damage to Ontario’s Greenbelt and and “undermine the credibility” of the highway.

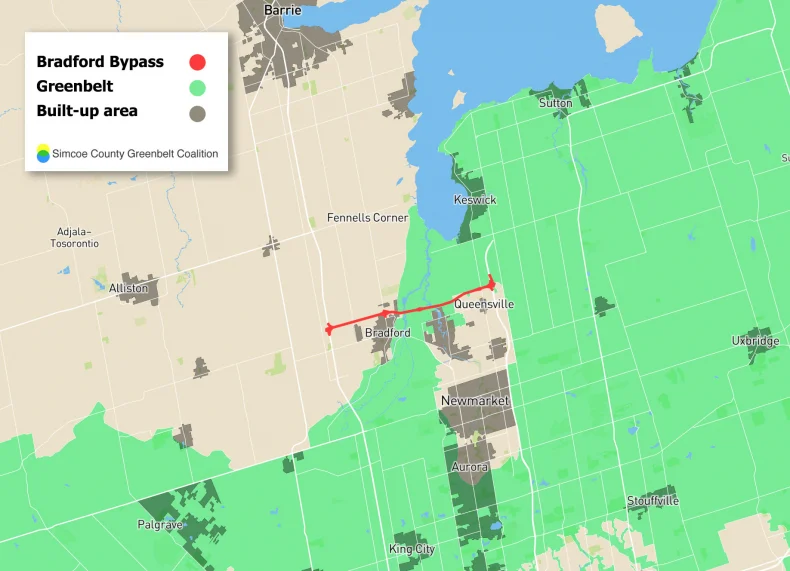

Like Highway 413, the Bradford Bypass is an idea that dates back several decades. It’s also located in Toronto’s outer suburbs, and it would also run through the Greenbelt. But the bypass is markedly different, too: the municipalities along the route remain staunchly in favour, the federal government decided not to intervene and it comes with a unique set of environmental concerns.

“They’re kind of a bit like apples and oranges,” Doyle said. “I wouldn’t say one is worse than the other. They’re both bad from an environmental perspective.”

The bypass would connect the two often-congested main routes drivers use to go north from Toronto. Many locals — accustomed to bumper-to-bumper traffic, especially on summer Fridays as city residents pass through en route to cottage country — have supported the project since its inception. Mulroney has said the new highway would cost $800 million to build, while the Toronto Region Board of Trade has estimated it would be roughly $1.5 billion.

In the 2000s, the Dalton McGuinty Liberal government shelved the bypass amid promises to increase access to public transit. McGuinty’s successor, Kathleen Wynne, put the highway back into long-range plans in 2017, but the project didn’t move forward until the PCs formed government.

Ford and Mulroney announced the bypass was back on the books at Bradford’s Carrot Fest in 2019. “I give all the credit to Caroline [Mulroney],” the premier said, calling the transportation minister an “absolute champion.” The government has said the highway would save drivers up to 35 minutes on average for the length of the route.

The route would cut through the Holland Marsh section of the Greenbelt, which is nicknamed “Ontario’s vegetable patch” for its fertile soil. Settlers drained much of the marsh for agriculture in the 1920s; the highway would cut through the narrowest point of its remaining wetlands, which are supposed to be protected from development. It would also cross 27 waterways, including the Holland River, which drains into the already-threatened Lake Simcoe.

The bypass last received an environmental assessment in 1997, before the Greenbelt existed and before policies protecting the climate and Lake Simcoe were written. That review found that road salt from the highway could contaminate groundwater and the Lake Simcoe watershed, and that air pollution from the road could be higher than what’s recommended by current standards. It also noted that the Chippewas of Georgina Island First Nation, which is based on Lake Simcoe, had raised concerns about archaeological sites along the route.

The Ford government has exempted the project from undergoing another full review, though it has said it is updating the old assessment with a fresh round of studies. As with Highway 413, the province may put shovels in the ground before the studies are complete.

“The exemption from the Environmental Assessment Act doesn’t give me any confidence that we’re dealing with a high level of scrutiny,” Simcoe County Greenbelt Coalition executive director Margaret Prophet said.

“They’re choosing to go more behind closed doors.”

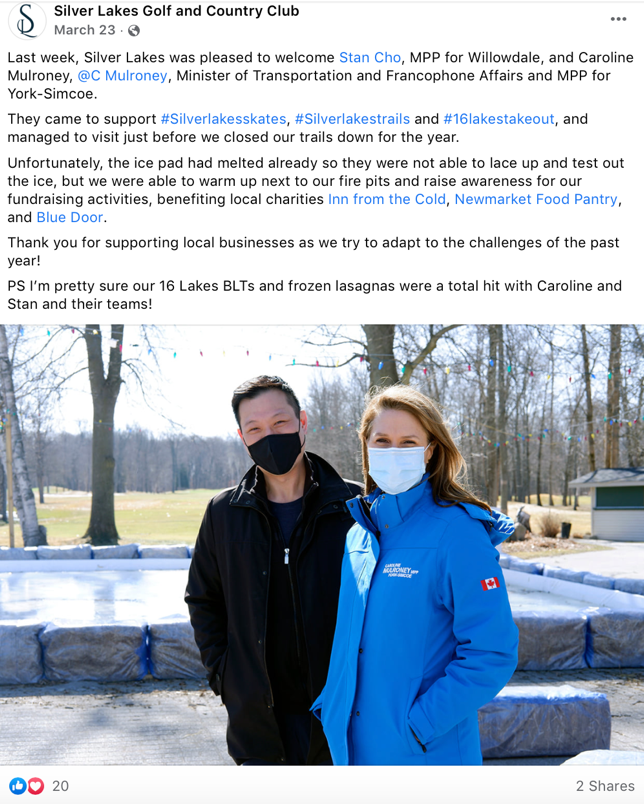

The Torstar/National Observer investigation into the government’s ties to the golf course being spared by the bypass was published on Oct. 31. The golf course is co-owned by MPP Stan Cho’s father. The route change was proposed in April — a few months later, Cho, who represents Willowdale in Toronto, became associate minister of transportation.

The government said Cho had declared a conflict of interest and neither he nor Mulroney applied pressure or directed ministry staff to alter the highway’s path. It also said the proposed route change was meant to avoid an archaeological site and minimize impact to the Holland River, and was done by ministry staff working with external consultants.

The story touched off a firestorm at Queen’s Park.

“Why should anyone trust the integrity of this government’s transportation planning decisions, when they seem to be driven by the private interests of landowners with ties to the PC Party?” NDP MPP Catherine Fife asked in question period the next morning.

Ford fired back, calling the bypass “exactly the type of project this province needs.”

“The Liberals and NDP are against building roads. They’re against building highways,” the premier said. “If it was up to them, they’d vote against a cow pasture… We’re a party of building infrastructure, and we’ll get this province moving again.”

On Nov. 2, the provincial NDP also surfaced a photo of Cho and Mulroney visiting the golf course in March, a month before the government proposed rerouting the bypass. The party filed a complaint with Ontario’s integrity cOn Nov. 2, the provincial NDP also surfaced a photo of Cho and Mulroney visiting the golf course in March, a month before the government proposed rerouting the bypass. The party filed a complaint with Ontario’s integrity commissioner the same day, alleging that Cho, Mulroney and Ford had breached ethics guidelines. The government denied the allegations, and the commissioner later cleared them of any wrongdoing.

In response, Mulroney defended the government, reiterating that she hadn’t consulted with Cho about the route. “Minister Cho and his family, immigrants to Canada, have worked hard to contribute greatly to our community,” she added.

“They are success stories that should be celebrated. The depictions of the Chos as anything but success stories is unacceptable.”

On Nov. 4, the provincial government announced it was upping its investments in its highway program, which includes Highway 413 and the Bradford Bypass. It plans to spend $8.6 billion until 2023-2024, which likely would not be enough to finish both projects. At the same time, the Tories pledged to spend even more on public transit.

A coalition of local groups asked a second time for the federal government to conduct its own assessment of the Bradford Bypass. The law allows multiple requests if there’s new information — the groups argued that because the Ford government exempted the highway from the provincial environmental assessment process since the last request from environmental groups, circumstances had changed.

They also argued that the Torstar/National Observer investigation into the project caused “escalating public concern,” which is one of the criteria Ottawa could use if it decided to conduct its own review. The groups hoped federal Environment Minister Steven Guilbeault — a former climate activist whose mandate letter specifically called on him to protect Lake Simcoe — would be more open to stepping in, but he declined the request on Feb. 10.

The minister’s office did not directly answer when asked whether the decision conflicted with his mandate letter. The Impact Assessment Agency of Canada said in a statement that the project would still be subject to provincial studies and the federal Fisheries Act, which applies to construction and maintenance near any fish-bearing water.

Though the Ford government is continuing to push forward with the project, its opponents are still trying other avenues to stop it. On March 14, 2022 seven environmental and community groups filed a court challenge of Guilbeault’s decision, alleging that it was not based on evidence: included among them are Environmental Defence, Rescue Lake Simcoe Coalition and Simcoe County Greenbelt Coalition, all represented by Ecojustice.

Federal Court Judge Angela Furlanetto sided with the groups on April 20, 2022, finding that Guilbeault’s decision didn’t meet the “threshold for transparency, intelligibility and justification and is unreasonable as a result.” However, Furlanetto stopped short of throwing out the minister’s choice out entirely, meaning that it remains valid.

Zoryana Cherwick, a spokesperson for Ecojustice, said the judgement may clear the way for the environmental and community groups make a third request for the federal environment minister to look at the Bradford Bypass. Guilbeault’s office didn’t immediately answer a request for comment.

Prophet said it’s clear no more big highways should be built if the Ontario government wants to protect waterways and the climate.

“We have done such a good job of brainwashing the average person (to believe) that highways are a net benefit to all of us, which isn’t the case,” she said. “It’s just not right.”

Updated March 21, 2022, at 12:30 p.m. ET: This article was updated to include news that seven environmental and community groups have filed a lawsuit seeking to challenge Guilbeault’s decision not to subject the Bradford Bypass to a federal review.

Updated Nov. 16, 2021, at 1:39 p.m. ET: This article was updated to include the second public request for a federal assessment of the Bradford Bypass, and the NDP request to the Auditor General to investigate the planning and procurement processes of both highways.

Updated on Feb. 15, 2022 at 11:00 a.m. ET: This story was updated to include the results of the integrity commissioner’s investigation into the routing of the Bradford Bypass, and details of the federal government’s second decision not to intervene with the project.

Updated on April 26, 2022 at 11:53 a.m. ET: This story was updated to include news that the government decided to route Highway 413 through a conservation reserve against the advice of consultants.

Updated on April 25, 2023 at 3:20 p.m. ET: This story was updated to include news of a Federal Court decision on a challenge of Guilbeault’s decision not to give the Bradford Bypass an impact assessment.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. Angello Johnson’s shoulders burn, and his arms...

Continue reading

B.C. allows industrial logging in critical habitat for at-risk species — part of the reason...

Lake sturgeon have long been culturally significant and nutritionally important to First Nations in Ontario,...

Mark Carney and the Liberals have won the 2025 election. Here’s what that means for...