In a Nova Scotia research lab, the last hope for an ancient fish species

Racing against time, dwindling habitat and warming waters, scientists are trying to give this little-known...

The federal government has warned Ontario that it’s willing to stall Highway 413 if the province doesn’t do a better job of consulting First Nations, internal documents show.

Highway 413, which would loop around suburbs in the northwestern Greater Toronto Area, is a signature project for Premier Doug Ford’s Progressive Conservatives. But the highway hasn’t moved forward very much since May 2021, when the federal government decided to step in and subject it to another layer of review.

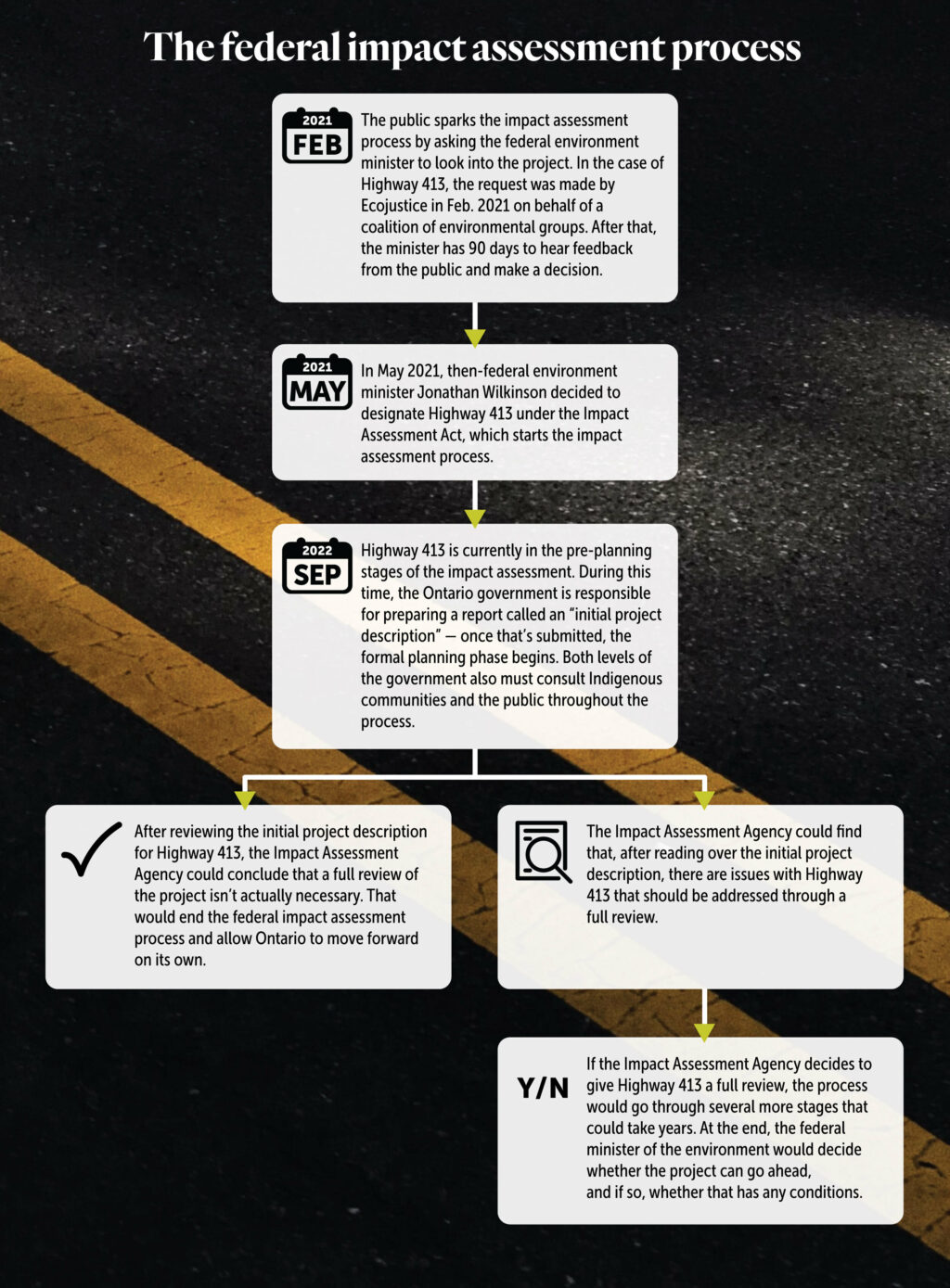

As part of that review, Ontario has spent the last year working on a preliminary report that the Impact Assessment Agency of Canada, which oversees the process, will use to decide whether a full-blown federal impact assessment is necessary. Feedback from Indigenous communities is one of the factors the federal agency must consider.

Early on in the process, some of that feedback raised red flags, new documents obtained by The Narwhal show. Two First Nations, Mississaugas of the Credit and Six Nations of the Grand River, have expressed dissatisfaction with the level of consultation so far. Ontario’s transportation ministry had also, as of June 2021, failed to incorporate traditional Indigenous Knowledge into highway plans or to consider the impact of the project on Indigenous communities, two other federal requirements.

Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation has long lived on a territory stretching from the Rouge Valley, at the east end of what is now Toronto, to the eastern shore of Lake Erie and the Niagara area. The nation, which has a reserve south of Brantford, Ont., told the Impact Assessment Agency that its dealings with Ontario on Highway 413 “felt more like information sharing than a two way dialogue,” according to minutes from a June 2021 meeting between the Ontario Ministry of Transportation and the agency.

Six Nations of the Grand River “noted similar concerns… regarding engagement to date,” the minutes said. The community’s territory is on land surrounding the Grand River west of Toronto, an area of land known as the Haldimand Tract, which the Crown granted to Six Nations in 1784. Six Nations also has a reserve south of Brantford.

Those “consultation issues” may be enough grounds for Ottawa to launch a full federal intervention, the agency warned, according to the minutes. That would subject Highway 413 to a more rigorous process that could delay it for years to come.

If the province wants to avoid a full impact assessment, the agency would want to get the “impression from the Indigenous Groups that they feel that their concerns will be addressed,” the minutes read.

“There is no expectation that every problem is resolved… However, it needs to be clear to [the Impact Assessment Agency of Canada] that there is a good relationship with stakeholders and Indigenous Groups in order to resolve issues moving forward.”

Concerns about the Ontario government’s consultation process persisted until at least last fall, when the Impact Assessment Agency again critiqued the province’s engagement with Indigenous communities.

In October 2021, the province submitted a draft of its preliminary report to the Impact Assessment Agency, which was obtained by The Narwhal through access to information legislation. In feedback for the Ontario government contained in that access to information request, the Impact Assessment Agency said the province’s work failed to include “specific concerns” raised by Indigenous communities and didn’t demonstrate “how their input was considered in the design” of Highway 413. Both things are required under federal rules.

Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation and Six Nations of the Grand River did not answer questions from The Narwhal by deadline.

In an emailed statement, the Impact Assessment Agency of Canada did not dispute the province’s minutes of the meeting, but said it can’t determine whether Ontario has resolved issues with Highway 413 until the Ministry of Transportation submits a final report.

Dakota Brasier, a spokesperson for Ontario Transportation Minister Caroline Mulroney, did not answer when asked what the province has done since 2021 to allay concerns from the First Nations and the Impact Assessment Agency. In an email, Brasier said the province is continuing to work on its final report.

“This is a complex process, and we are working diligently to meet the requirements so that we can deliver on our plan to build Highway 413 as soon as possible,” Brasier said.

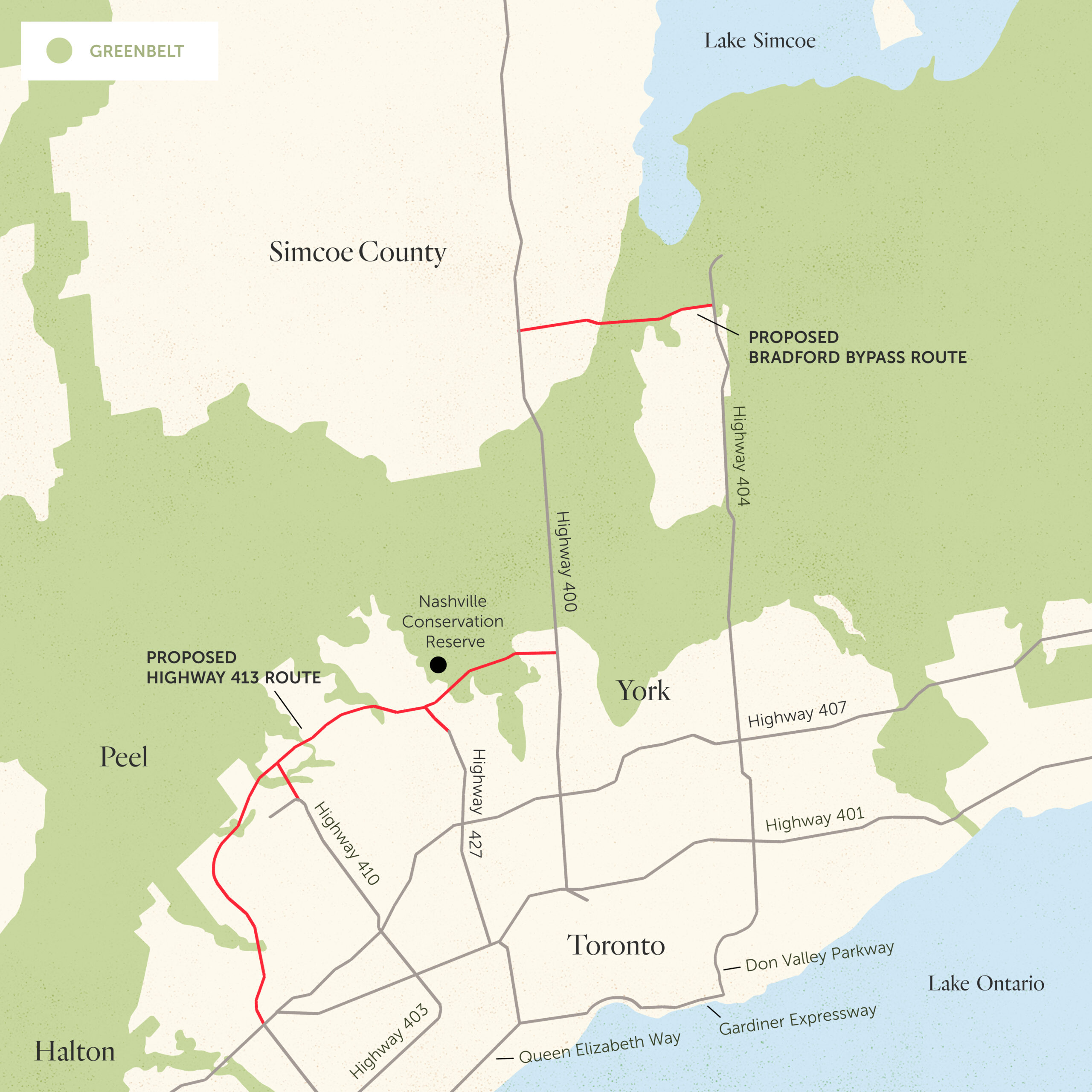

Highway 413, also called the GTA West Corridor, would run a 60-kilometre route between the Toronto suburbs of Vaughan and Milton. Opposition to the project has mainly centred on its environmental impact.

The highway would cut through Ontario’s protected Greenbelt and prime farmland. New highways tend to attract more traffic, which contributes to carbon emissions that fuel climate change. The highway would also go over 95 waterways, three conservation properties, five aquifers and 65 archaeological sites, according to documents reported by The Narwhal in June.

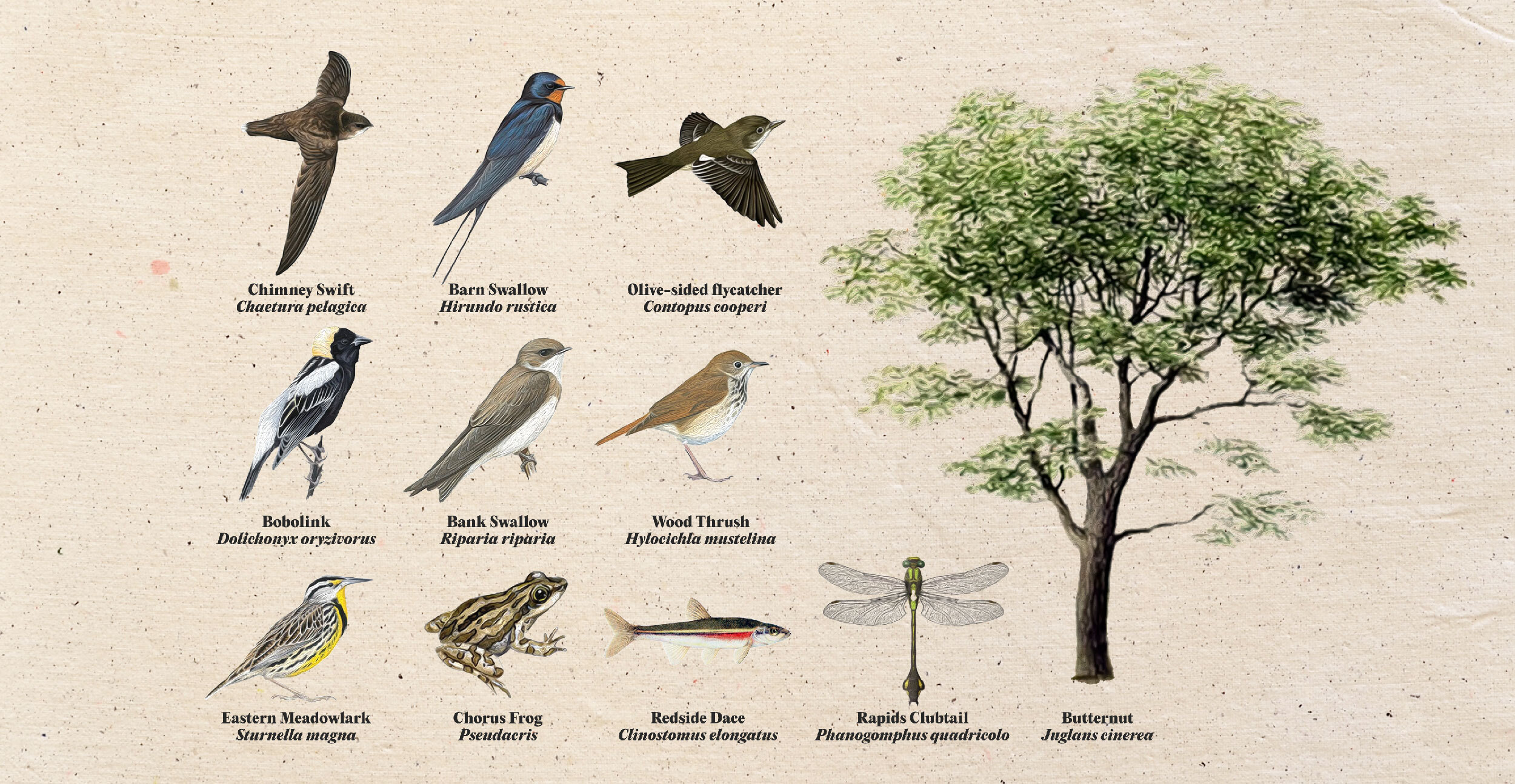

The same month, reporting by The Narwhal and the Toronto Star showed the province has quietly confirmed that 11 species at risk are living along the 413’s route. Two of those species — the western chorus frog and the rapids clubtail dragonfly — are federally-protected but not included in Ontario’s endangered species law, part of then-federal environment minister Jonathan Wilkinson’s rationale for intervening in the project in the first place. (Wilkinson also had concerns about a third species, the red-headed woodpecker, which the Ontario government hasn’t yet located along the highway’s path.)

The presence of the western chorus frog and the rapids clubtail already raises questions about whether Ottawa might be compelled to conduct a full assessment of the project. The problems with Indigenous consultation may also present a significant stumbling block for the 413, which is already behind the timeline the Ford government had pushed for. In 2020, Ontario proposed to begin early construction work before finishing its own environmental assessment, which was expected at the time to be done in 2022.

Another problem raised in the June 2021 meeting, according to the Ministry of Transportation’s agenda: by its own admission, the provincial government had not done work by that point to fulfill federal requirements to incorporate traditional Indigenous knowledge into its plans, and consider how Highway 413 might impact Indigenous communities.

“No traditional knowledge has been provided/gathered to date and no consideration of how the Indigenous communities may use the land in the future,” the ministry’s meeting agenda said.

In her email, Brasier did not directly answer when asked whether Ontario is concerned that consultation issues could hold up Highway 413.

“To be clear – the principal elements of concern raised about this project by the federal government specifically relate to the potential adverse effects on the western chorus frog, red-headed woodpecker and rapids clubtail dragonfly,” Brasier said.

Highway 413 isn’t the first Ontario government project to stir concerns around consultation with Indigenous communities. In the Far North, Neskantaga First Nation has said Ontario’s consultation on proposals to build roads to the Ring of Fire region are “inadequate.” And in 2020, Chapleau Cree, Missanabie Cree and Brunswick House First Nations filed a lawsuit alleging the Ontario government didn’t properly consult them on its plans to manage forests in their territories.

Canadian courts have affirmed again and again that governments have the duty to consult Indigenous people on projects affecting their rights or on their territories. But it would be very unusual for a government acting on its own to put the brakes on a project over Indigenous consultation concerns. And the federal government’s impact assessment law is still fairly new, so there’s not a lot of precedent for what happens next.

In its email, the Impact Assessment Agency confirmed that it has not received another draft of Ontario’s report. It’s not clear how long it might take for the province to file a final version.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On March 17, federal Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre...

Continue reading

Racing against time, dwindling habitat and warming waters, scientists are trying to give this little-known...

From investigative reporting to stunning photography, we’ve been recognized with four 2024 CAJ Awards nods...

The Narwhal is expanding its reach on video platforms like YouTube and TikTok. First up?...