The site of an infamous B.C. mining disaster could get even bigger. This First Nation is going to court — and ‘won’t back down’

Xatśūll First Nation is challenging B.C.’s approval of Mount Polley mine’s tailings dam raising. Indigenous...

This photo essay is part of The Narwhal’s BIPOC Photojournalism Fellowship, operated in partnership with Room Up Front and made possible by The Reader’s Digest Foundation and the generosity of The Narwhal’s readers.

For some people living alongside the farmland and forests outside of Toronto that the Ontario government wants to turn into a road, Highway 413 is a route to opportunity.

For others, the proposed project — and the damage it could cause to the environment — represents the opposite of the future they want.

Whether it’s built or not, what happens with Highway 413 will shape the communities along its route for decades to come.

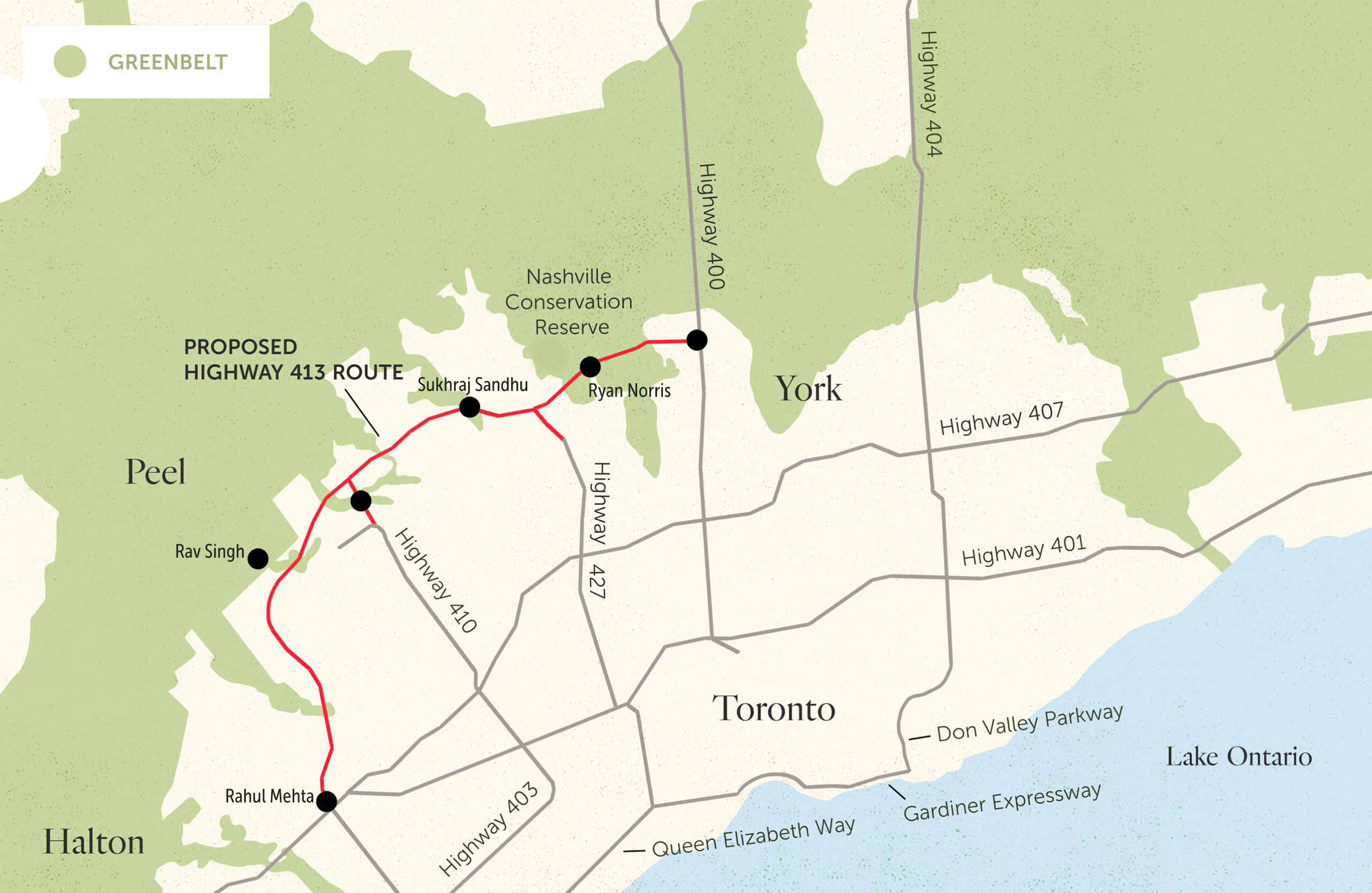

Highway 413, if it becomes a reality, would draw a 60-kilometre path connecting the Greater Toronto Area suburbs of Vaughan and Milton. It would also cut through Ontario’s Greenbelt, conservation land, at least 220 wetlands, dozens of waterways, 2,000 acres of farmland and the habitats of at least 11 species at risk.

The previous Liberal government shelved the idea over environmental concerns, and after an independent panel found it would save most drivers less than a minute. But Premier Doug Ford’s Progressive Conservatives revived it in late 2018, arguing that it’s necessary to clear up the Greater Toronto Area’s relentless problem with traffic — and that it could actually save drivers half an hour.

“Congestion is a real problem, and members of the opposition just want to keep their heads in the sand and not recognize this reality that plagues people — drivers, commuters, families, workers, farmers,” Ontario Transportation Minister Caroline Mulroney said last year.

Others, however, point to research showing new roads attract more drivers, making the new lanes just as congested as the old ones. The worry, environmentalists say, is that we could lose important places and encourage emissions-heavy car traffic without actually solving the problem.

“The truth is that when you build more highways, you get more congestion, because beautiful new highways incentivize people to drive,” Gideon Foreman, a climate change and transportation policy analyst at the David Suzuki Foundation, says. “And we’ve seen this all over the world, you put a new highway in, and people want to use it. And when people use it, there’s a word for that. It’s called congestion. So we’ll be right back where we started.”

The Progressive Conservatives made the highway an election issue in 2022, and won a second term in government. But the 413 is stalled in bureaucratic gridlock for now: last year, amid a surge of opposition from citizens and local governments along the route, the federal government stepped in and said it would do its own impact assessment. Since then, Highway 413 hasn’t substantially moved forward, and it’s not clear when or if it will.

Still, the 413 is a flashpoint for many of the huge questions now facing communities as they decide how they want to live. Should people drive, take transit, or both? How much greenspace should there be? Where will the region’s food come from? Ultimately, the question is somewhat existential — what will southern Ontario’s future look like, and who gets to decide?

Over six months in 2022, The Narwhal travelled the proposed route of the 413. Here are the stories of four people whose lives will be shaped by the highway, for worse or for better.

Ryan Norris grew up in Etobicoke, on the western edge of Toronto. He has witnessed the shrinking of conservation areas in the Greater Toronto Area, as well as the targeting of the Greenbelt in his lifetime. Now, he’s an associate professor at the University of Guelph’s department of integrative biology, and for him, Highway 413 is an issue that lies close to home.

“It wasn’t that long ago that you could travel along Highway 7 … and basically go through farmland that was past the northern extent of the [Greater Toronto Area], 40 to 50 years ago. And of course, now that’s swallowed up by the city,” Norris said.

“And the 413 will continue in the tradition of swallowing up the city, swallowing up farmland and natural areas that we … frankly, we need to survive.”

Hoping to inspire others to experience the remaining nature firsthand, he has been leading walks through the Nashville Conservation Reserve in Vaughan — which the highway would cut through — for the past year. Norris, who was partially inspired to become a scientist through his exposure to nature as a kid, believes that these experiences are vital for future generations. Gideon Foreman, a transportation policy analyst from the David Suzuki Foundation, also helps lead the walks.

With an estimated 11 to 29 species at risk living along the route of the highway, even an hour’s walk through the Nashville Conservation Reserve is likely to reveal glimpses of the area’s rich biodiversity, from monarch butterflies to goldfinches.

Sukhraj Sandhu spends the majority of his time on the road: he’s regularly behind the wheel from 6 a.m. to 9 p.m. His livelihood relies on highways, and gridlock often slows his schedule to a standstill. As Sandhu weaves across Canada and the U.S., he hopes for a future with more road infrastructure, enough to serve national and international supply chains, and the multiplying warehouses where he lives: Brampton, a growing city that’s part of Peel Region west of Toronto.

Peel Region houses some 80 per cent of all companies in the Greater Toronto Area. Around 40 per cent of all Amazon packages delivered to Canada go through the region for processing. It’s home to an estimated 2,000 trucking companies and approximately 68,000 vehicles transport cargo along Peel Region roads every day, carrying goods worth $1.8 billion annually. To Sandhu, those numbers are a clear sign of the need to clear up congestion.

Highway 413 opponents have argued that the road isn’t needed, since in many spots it would run parallel to Highway 407, which isn’t at capacity. A tolled 400-series highway that was itself meant to deal with congestion around Toronto, the 407 opened in 1997. Built with public money, it was leased to a group of private companies for $3.1 billion for 99 years only two years after it was built.

The tolls have risen by over 200 per cent since 2015, from about 10 cents to over 60 cents per kilometre during rush hour. That makes a 70-kilometre roundtrip from the suburban city of Markham, Ont., to Pearson International Airport in Mississauga about $40, before gas. About 262,748 daily trips are taken on the 407 daily, compared to the 420,000 daily vehicles on the region’s other east-west highway, the ever-gridlocked 401, which some say is North America’s busiest highway.

Sandhu has heard suggestions that subsidies or reduced rates for the private 407 would be better than building a new highway. But he believes that with the return of traffic at the heels of COVID-19, any support would still be insufficient. He also believes that the companies that run the 407 would simply keep raising toll rates if more people started using it.

During a drive through Brampton last October, Sandhu commented on the beauty of autumn leaves as he passed by old orchards and the edge of the Claireville Conservation Area. He noted how fast the city is growing, saying that its residents’ needs must be served better.

Sandhu believes the majority of Brampton residents — especially truckers — are in favour of the 413. “So give the good luck to Mr. Doug Ford and their whole team and the Conservative Party of Ontario,” he said. “They made promises with our people, with our truckers. So let’s see if they fulfill it — we wish they start as soon as possible.”

“Miti” means “soil” in Rav Singh’s mother tongue, Punjabi: she comes from a multi-generational family of farmers in India. The name of her farm is her way of connecting it to her ancestral roots as she carries on that tradition in Canada.

Singh designed her farm to focus on justice: food justice, a holistic and structural view of the food system that considers healthy food a human right, and climate justice, which recognizes the disproportionate impacts of climate change on marginalized communities around the world. But the land she rents is just one kilometre from the proposed route of Highway 413, and Singh said she won’t be able to continue farming if it’s built.

“I would have to move further away to access farmland, which is not feasible for me and many other young and new farmers. Likely, I would have to switch to another profession,” Singh mused, imagining a future where the highway is built.

Singh notes that Ontario farming is currently in crisis due to urbanization of agricultural land: increased competition with wealthy developers for property is just one reason she believes the 413 would contribute to pushing out young farmers, like her. Released earlier this year, Canada’s 2021 census of agriculture found that Ontario is losing an average of 319 acres of productive farmland every day. Since 1996, Ontario has lost 1.5 million acres of productive farmland — an area roughly the size of Toronto, Peel Region, Halton Region, Waterloo Region, Hamilton and Niagara Region combined.

In addition to the disruption of the road itself, Singh is worried that its rippling effects — such as winter road salt run-off — would impact the quality of the soil her vegetables grow in. She says the Mississauga region has some of the richest top soil in the world and would take thousands of years to rebalance, if it were to ever recover from the highway’s construction.

Ontario’s auditor general estimates Highway 413 will cost more than $4 billion to build: Singh said she wishes governments would put that level of funding towards strong, affordable and reliable public transit, as well as infrastructure for safe cycling and walking. She believes that would get cars off of existing highways and free up space for people who actually need the road, as would policies that support remote work and liveable wages.

“Right now, the only way someone can get around easily is by car … I understand the need for more infrastructure to connect our communities. But using the same method which we have been [using] for decades — and a method which is proven to actually increase congestion and not decrease travel time — is not the answer,” Singh said.

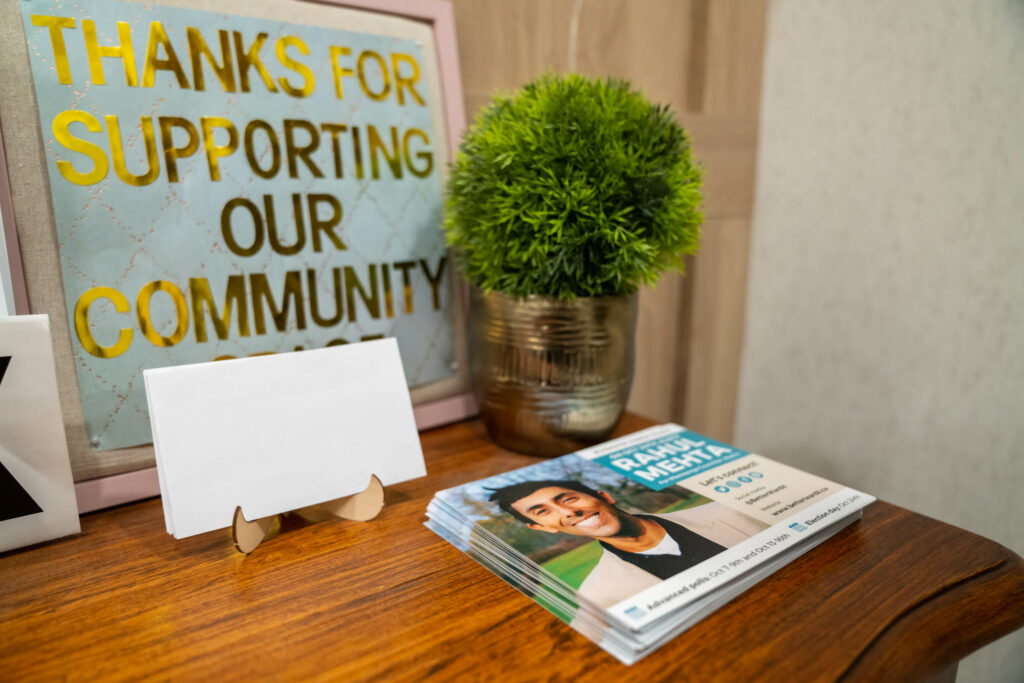

Ever since the Ford government revived Highway 413, activists have been campaigning against it. One of them is Rahul Mehta, a sustainability advocate and recent candidate for city councillor in Mississauga, where he lives.

For the past few years, he has been regularly involved with initiatives such as Stop the 413 and Mississauga Green Drinks, groups that stand for sustainable urban planning and oppose the highway proposal. The Harvest Walk last year showcased sections of the route to those unfamiliar with the proposal.

“It is a thrice redundant highway,” Mehta said, meaning there’s no need for the 413 when Highways 401 and 407 already exist. “Ultimately, this is so much more than just about the highway. It’s about pollution, long-term legacy impacts, downstream impacts to the communities to the south like Brampton and Mississauga, and perpetuating a car culture and sprawl culture that actually has led to even less affordable housing, even less ability to live, work and play in our communities.”

“All while we’re losing some of the last nearby farmland and greenspace that so many of our residents are craving.”

Mississauga is infamously car-centric, but Mehta doesn’t want to move from the place he calls home. He dreams of living in a suburb that breaks from the traditional model of large single family homes whose residents need multiple cars, and would love to see his city become a place where options such as biking are considered at the same level as driving. “It’s not about vilifying the car … How do we break this hierarchical structure where the single family home is king? And the car is king as well?”

With files from Emma McIntosh.