The Narwhal picks up National Magazine Award nomination for Amber Bracken’s oilsands photojournalism

Bracken was recognized for intimate portraits of residents of Fort Chipewyan, Alta., who told her...

In the first four days after applications opened for companies to access $1.7 billion in federal funding to clean up inactive wells in Alberta, the province has been inundated with nearly 20,000 applications.

While much of the political and media focus has been on orphan wells — those left behind without an owner — they are just the “tip of the iceberg,” Nikki Way, senior analyst at the Pembina Institute, told The Narwhal.

“The bulk of the work that needs to be done is still in the hands of private industry.”

That work involves the sealing off and cleaning up of tens of thousands of inactive wells across the province, still owned by private companies that haven’t had the means — or the incentive — to clean them up.

Some of those wells have been languishing on the landscape for decades.

With federal funds flowing to private companies to clean up the wells, questions are now being raised about whether that funding provides a transfer of taxpayer money to the oil and gas industry — and what strings might be attached.

“It was a good compromise right now. These are very unusual times,” Barry Robinson, a Calgary-based lawyer with Ecojustice said, noting the funding means more jobs and a reduction of environmental risk.

But, he added, the problem of companies not cleaning up wells is “a bigger problem to fix.” Too often, he noted, companies let wells sit for years or decades instead of paying to clean them up.

For Lucija Muehlenbachs, associate professor of economics at the University of Calgary, the program has good goals — it reduces environmental risk and creates jobs in the short term — but confuses the message to companies. As she put it, it sends a “bad signal.”

“Are companies thinking, ‘OK, why should I clean [a well] up because eventually the government is going to pick up the bill?’” she asked.

“It’s a good idea to try and facilitate as much of that [cleanup] work as possible,” Way said. “But it’s key that the public isn’t exposed to that risk.”

And that, she says, means ensuring public money isn’t handed out without “policies that address the root causes of the growing liability issue.”

We looked into how we got here — and what experts are saying the province can do about it, especially with an extra billion dollars floating around.

Last month, the Alberta government made the first announcement on how it will spend $1 billion in federal money it is receiving to encourage the cleanup of inactive wells across the province.

The money is part of a $1.7 billion package for well cleanup announced by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau in April — an olive branch extended to the beleaguered oil and gas industry, hit hard by a supply glut and reduced demand as a result of COVID-19.

Trudeau’s announcement initially attracted the praise of environmental groups, industry and the Alberta government alike. Energy Minister Sonya Savage called it “a job-creation program that has the added benefit of being an environmental program.”

As part of the package, a $200 million loan is being extended to Alberta’s Orphan Well Association, to expedite the cleanup of the province’s roughly 7,000 orphan well sites requiring some kind of site cleanup, be it sealing or remediation.

Then there’s another billion dollars in funding — not a loan — going toward cleaning up inactive wells in Alberta.

Friday was the first day oil and gas service companies across Alberta could apply for government funding to clean up inactive wells — and there’s quite a bit of money to go around.

The Alberta government is allocating the federal money through what it dubbed its Site Rehabilitation Program.

The program will provide grants to service companies that complete cleanup work on inactive well sites — funding up to 100 per cent of the total cost of the work. Normally, the company that owns the well would be responsible for picking up the cleanup tab.

How much the government pays is “dependent on the ability of the oil and gas company responsible for the site to help pay for cleanup,” which implies that companies in precarious financial situations may be off the hook entirely for the cleanup of wells accepted into the program.

As Energy Minister Sonya Savage put it to The Globe and Mail, the first phase of the program will be aimed at wells owned by companies that “don’t have two pennies to rub together right now.”

The government says the program will create 5,300 direct jobs and will result in the cleanup of thousands of well sites.

The Government of Alberta reports the province has some 91,000 inactive wells.

The Narwhal previously reported on internal documents showing the Alberta Energy Regulator has privately projected that the number of inactive wells in Alberta could double to 180,000 by 2030.

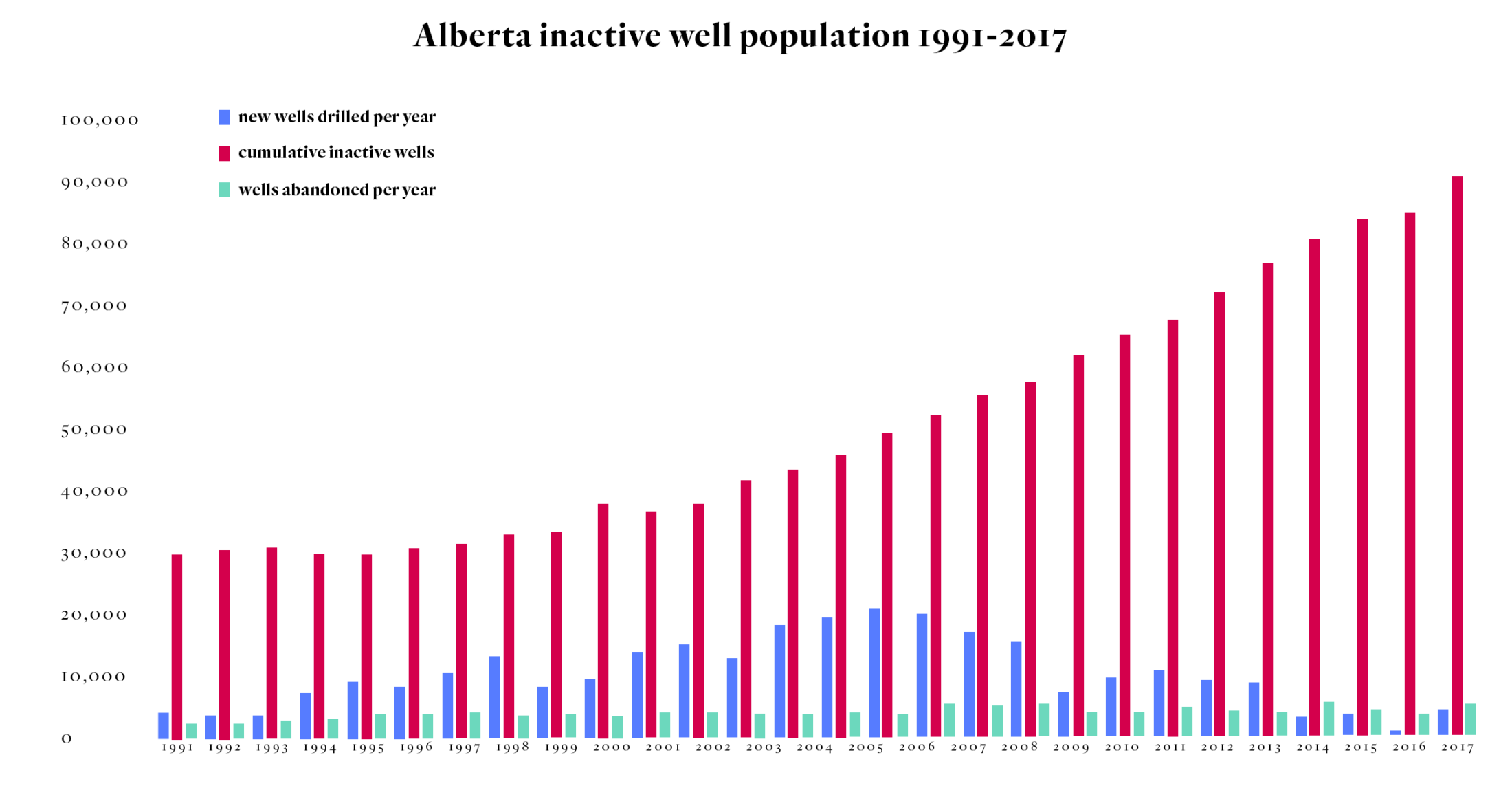

As Robinson pointed out, the number of inactive wells has continued to climb in the province — and not just when times are tough.

“You’ve got to remember that when oil was $60 or $80 a barrel, the number of inactive wells went up every year,” he said. “The number of inactive wells has just been going up, up, up, up, up.”

“The trend has been up for a very long time.”

The problem of inactive wells has grown by six per cent each year on average, according to a graph obtained through a FOI request. An “abandoned” well, in a confusing bit of industry jargon, refers to the proper sealing of an inactive well. Graph: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal. Source: Alberta Energy Regulator

According to an internal presentation from the Alberta Energy Regulator, the number of inactive wells has grown by six per cent each year.

The government also reports the province has another 73,000 “abandoned” wells. Abandoned wells can still be owned by a company. In a confusing bit of bad jargon, they are not the same as orphans. Abandoned wells have been permanently sealed, but the site has not been cleaned up.

Taken together, the number of wells no longer in use is roughly the same as those still pumping oil and gas.

Wells can be left to sit inactive — rather than being sealed and cleaned up — on the chance they may again one day produce oil or gas, and once again garner a profit for their owner.

In reality, that seldom happens.

According to a 2017 briefing paper from the University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy, “the vast majority of these wells will never be reactivated, no matter how dramatically conditions improve.”

The paper found that even “if oil prices rise 200 per cent, the modeling shows that just 12 per cent of oil wells become reactivated, and just seven per cent of gas wells.”

In the current situation where negative oil prices are making headlines, oil prices are certainly not rising by 200 per cent.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, an internal presentation from the Alberta Energy Regulator showed that less than 0.2 per cent of wells that have sat for 10 years were reactivated.

And the longer an inactive well sits, experts say, the higher the risk of problems.

Not every inactive well is a risk to human health, the environment or agriculture.

But some are.

“The longer a well sits inactive, the more likely it’s either leaking methane, a greenhouse gas X times more potent than carbon dioxide, to the surface or the more likely the pipe is broken down and you’re leaking contaminants into groundwater,” Robinson said.

“In a nutshell, the longer a well sits, the greater the risk of some sort of environmental harm.”

No.

Last year, B.C. became the first province in western Canada to introduce timelines for how long a well can sit dormant before it needs to be sealed and cleaned up. Similar regulations exist in Texas and North Dakota.

Nothing of the sort exists in Alberta.

In essence, leaving a well to sit on a landscape becomes an economic decision for the company that owns it.

On one hand, plugging the well, remediating the soil and obtaining a reclamation certificate can be expensive — some wells may incur costs in the hundreds of thousands of dollars.

On the other hand, until a reclamation certificate is issued, a company is required to pay rent to the landowner, and any taxes it owes to local governments. (Though, as The Narwhal has previously reported, Alberta companies have been increasingly not making rental payments and are behind on their tax payments.)

In the end, for close to 100,000 wells across the province, it makes more sense for many companies to just to let them sit there.

Muehlenbachs, the economics professor, isn’t convinced timelines alone would solve the growing problem of inactive wells.

She argues instead that an additional incentive could be put in place to prevent companies from leaving wells to sit idle indefinitely, pointing to California as an example.

In that state — where there are approximately 100,000 wells, representing a cleanup liability of an estimated US$9 billion — regulators have put in place what’s called an idle well fee. In essence, if companies want to leave a well sitting on the landscape, they have to pay. Fees range from US$150 to US$1,500 per year.

Muehlenbachs thinks that could be done in Alberta, too. “A smart policy would be to put a price tag on inactive wells and make that increase with age,” she told The Narwhal.

Advocates have long been calling for the province to put in place tougher regulations to stop the growth of inactive wells, arguing that the environmental risks — and the chance that unprofitable wells might end up orphans — are too great for Albertans to ignore.

The Pembina Institute has argued for full securities or bonds when a company applies to drill a new well.

This would require companies to post the full cost of cleanup prior to drilling, and reaping the profits from drilling. The bond would only be returned once the well was properly plugged, the site cleaned up and a reclamation certificate issued — possibly in stages, to incentivize a company to move along the steps.

To Muehlenbachs, a bond would be a reasonable expense for a company wanting to drill a well. “I mean, new wells are so expensive, what is a bond to these companies?” she wondered.

Although it has been reported that the federal funding for cleanup comes with “a provincial commitment to implement strengthened regulations to prevent this problem from reoccurring,” no details have been released.

“We’ve gotten commitments by the government of Alberta to strengthen regulations so we see fewer orphan and inactive wells in the future,” Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said, according to CBC.

For now, advocates are left wondering what that might look like.

Asked for comment, the Prime Minister’s Office referred The Narwhal to Natural Resources Canada, which referred The Narwhal to the Department of Finance, which did not answer questions by publication time.

“I would want to see the details of that system,” Robinson said.

“Alberta over the last 40 years has many times said, ‘oh, here’s our program to fix this problem.’ And the program has never been effective.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. Angello Johnson’s shoulders burn, and his arms...

Continue reading

Bracken was recognized for intimate portraits of residents of Fort Chipewyan, Alta., who told her...

A guide to the BC Energy Regulator: what it is, what it does and why...

The B.C. government has introduced legislation to fast track wind projects and the North Coast...