B.C. has a new policy for staking mining claims. Why doesn’t anyone like it?

B.C. previously allowed mineral claims without First Nations consultation. It was court-ordered to fulfill its...

From the air, what stands out is the water. Rivers and streams too numerous to count, winding through a vast expanse of peatlands and forests, reaching towards the glimmering waters of James Bay.

This landscape hundreds of kilometres northeast of Timmins, Ont., is among the most pristine, biodiverse regions left on the planet. The chilly saltwater of Weenebeg and Washaybeyoh, or James Bay and Hudson Bay, is home to belugas, narwhals and walruses. Eelgrass meadows sway in the shallows. Dozens of bird species migrate through tidal marshes and coastal wildflower meadows. The world’s southernmost population of polar bears hunts seals on winter sea ice. Further inland, herds of caribou migrate through one of the largest complexes of carbon-rich peatlands in the world and sturgeon swim in some of the last undammed rivers in Ontario. Wetlands and bogs dot the landscape in every direction.

The Omushkego people have understood the importance of these lands and waters since time immemorial. The soggy muskeg of the lowlands, for example, stores an enormous amount of carbon, helping regulate the global climate — Omushkego call them the Breathing Lands, the lungs of the world. The shoreline of the bays is called the Birthing Place. Gigantic flocks of birds migrate from across North America to breed here and only here.

Now, the federal government is starting to catch on to the region’s ecological importance. The Breathing Lands and huge sections of the bays are at the centre of a recent push to establish a massive Indigenous-led conservation project at the northern edge of what’s now called Ontario.

“It is up to us to fight to keep it green, to keep it pristine, to keep it breathing,” Amos Wesley, a deputy chief of Mushkegowuk Council, told a crowd at a celebration earlier this year.

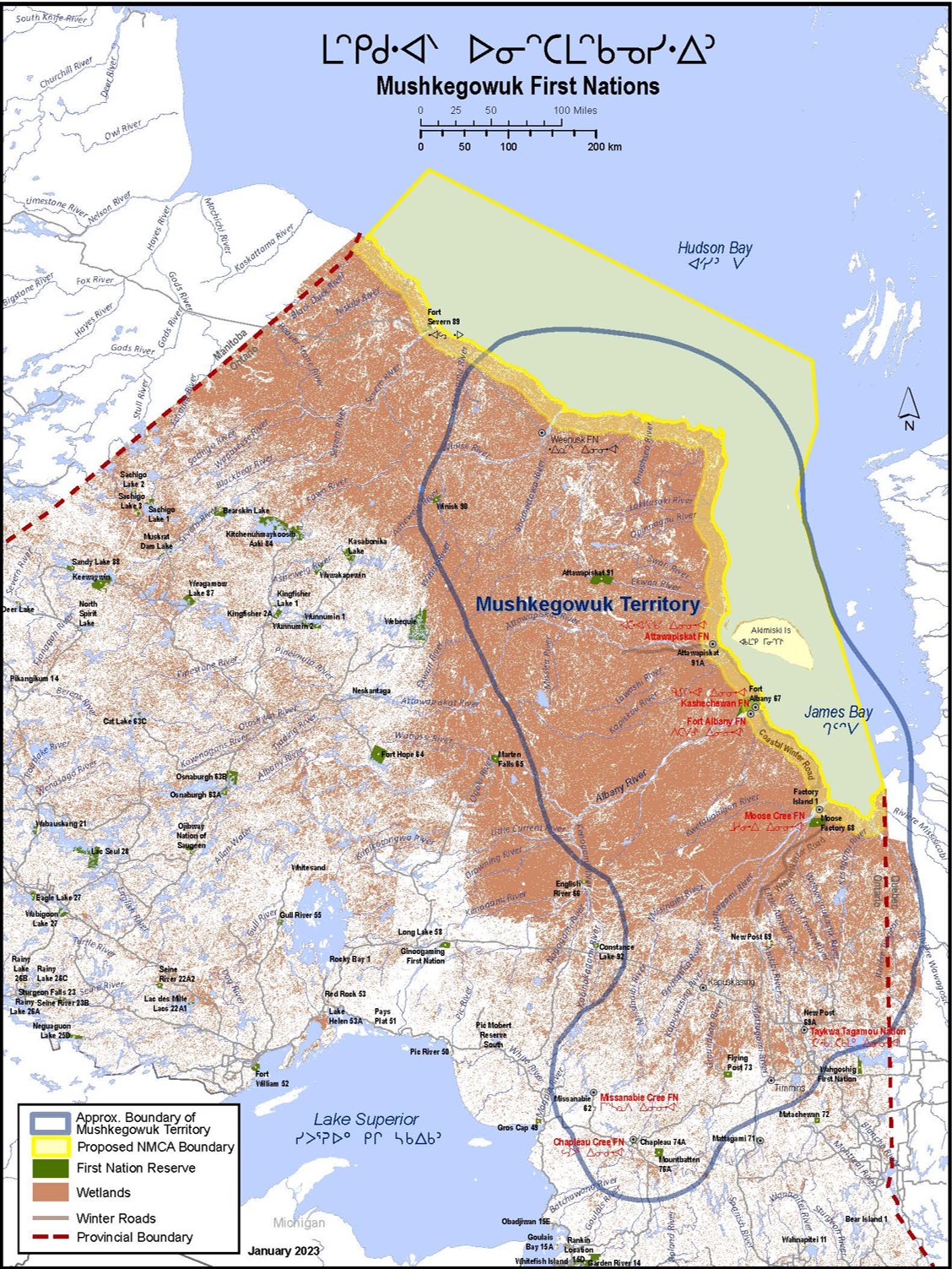

The project is led by the Mushkegowuk Council, acting on behalf of the seven Swampy Cree First Nations it serves in far northern Ontario, and two others who have signed onto conservation efforts. Exactly what “Indigenous-led” will mean for governance and decision-making in practice isn’t quite settled yet. Portions of the work are also moving forward under the federal Project Finance for Permanence program, announced in 2022, which set aside $800 million for four key Indigenous-led conservation projects.

In February, Mushkegowuk Council and Parks Canada jointly announced the feasibility study for the first part of the plan, a marine conservation area, had been formally accepted. Representatives from Omushkego communities gathered to celebrate the milestone for three days in Kashechewan, a community nestled on the banks of the Albany River near Weenebeg. They hope to have initial agreements for a land-based conservation project signed this summer. The council is also set to negotiate funding and final details with Parks Canada on the marine conservation area this spring.

Consensus is vital to co-ordinate work on such an enormous scale, but getting everyone to the table is a challenge. Mushkegowuk communities have few reasons to trust Canadian governments, and many reasons to be skeptical about partnering with them.

“It seems to be a lot easier to get consensus from the community members. They all agree that we need to protect the land and resources,” Lawrence Martin, the head of Mushkegowuk Council’s lands and resources department, told reporters in Kashechewan.

“But it’s the chief and councils that are afraid to make that commitment to sign any document still. I think it just requires more time … for them to understand it.”

Though some might feel it’s moving too quickly, Martin said, it’s really a window of opportunity years in the making — one that he worries may close if the council waits too long.

The council declared its commitment to protecting the Breathing Lands and the Birthing Place in 1974, and has resolutions on record as early as the 1980s, calling for the creation of an Omushkego Tribal Conservation Authority to conserve lands and waters. Now, they may finally have the opportunity to realize those ambitions, and transform them into legal, permanent protections.

“Finally, after 50 years … it’s here,” Martin said.

Treaty 9, which covers a gigantic swath of the most northern portions of Ontario, was based on dishonesty from the beginning. When it was negotiated in the early 1900s, Crown representatives said Indigenous leaders would retain the right to use their territories as they always had, but inserted a clause in English stating the opposite. The Treaty document wasn’t translated into Cree or any other Indigenous language. Now, 10 First Nations are suing the Canadian and Ontario governments over what they allege is a century of broken promises.

The impacts of colonization persist today in the form of long-term boil-water advisories, housing crises, youth suicides, poverty and high food costs. Trauma from residential schools reverberates across generations, while Canada’s child welfare system continues to separate families and communities. Many young people still have to leave northern communities to access education. And the creation of the national Parks Canada system dispossessed Indigenous people of their homelands, a colonial legacy that left deep scars.

Community trust isn’t the only hurdle: the proposed conservation area lies within land the Ontario government claims jurisdiction over, and so far, the province hasn’t publicly supported Indigenous-led conservation in general. It has, however, granted mineral claims in the far northern reaches of the province — mining companies will now have to be part of the conversation too.

Navigating all of that takes time, and this project might not have a ton of it. The idea has federal support and dollars right now, right this second — which could easily be erased if the governing Liberals lose the next election, scheduled for June 2026, an outcome polls suggest is not only possible but likely.

A spokesperson for federal Conservative leader Pierre Pollieve, the current frontrunner in the polls, didn’t respond when asked whether the party would support Indigenous-led conservation work if elected.

Omushkego leaders have been talking about the need for large-scale conservation in their homelands for decades. In the 1960s and ’80s, plans to dam the mouth of Weenebeg sparked massive backlash — research found it could knock out all marine life in the bay and the project failed, despite support from then-prime minister Brian Mulroney. Mining has also been a longtime environmental concern. The De Beers Victor Mine near Attawapiskat First Nation, which operated from 2008 to 2019, is an example of why. A group from Attawapiskat blockaded the diamond mine in 2013 amid concerns over whether the economic benefits of the project were actually helping the community. The company pleaded guilty in 2019 to failing to report data on mercury levels in local waterways.

The current push for conservation here began around 2019 as word spread of the Grand Council of the Crees’ plans to create a protected area on the Quebec side of James Bay. The same year, the federal Liberals signalled openness to such projects, announcing commitments to conserve 25 per cent of the land and oceans in Canada by 2025, then 30 per cent by 2030.

Right now, Martin is at the helm of the project. He’s someone with a long record of running various things, and of convincing people to get on board. Martin grew up in Moose River Crossing, a small northern Cree community, moving south to North Bay, Ont., for high school. He’s a musician who’s toured the world under the name Wapistan. He worked for a police service, and at a radio station. He ran a health centre. He’s been mayor of two Ontario cities: Sioux Lookout and Cochrane. He’s also been Mushkegowuk Council grand chief twice.

The Omushkego plan Martin and his team have been working on, detailed in hundreds of pages of a feasibility study and a draft plan, is for an Indigenous-led conservation project about five times the size of Nova Scotia. The first piece, and the one that’s furthest along, is a marine conservation area. It includes a 20-kilometre coastal buffer — an area called Aski-Gitchi Bayou, or the place where the land expands out into the waters — along with the western portion of Weeneebeg (James Bay) and a decent chunk of southern Washaybeyoh (Hudson Bay). The total area being studied is 91,000 square kilometres, with 1,290 kilometres of coastline — longer than that of Hawaii, and roughly the distance from Toronto to Winnipeg.

The project strategy weaves western science with a wealth of Traditional Knowledge. The feasibility study for the Mushkegowuk marine conservation, for example, includes 124 interviews with 94 Omushkego land users. “We’ve only begun to scratch the surface on these interviews,” the report reads. “They are an irreplaceable source of knowledge and information.”

What they heard from community members, Martin said, was fear of the changes people are already seeing as global temperatures rise. New species of birds and fish moving farther north, caribou migrating differently. This past winter was particularly, unsettlingly warm, with a combination of an El Niño weather pattern and climate change leading to a lack of snow and melting ice roads.

“We had to pay attention to what the people were seeing, what they were saying,” Martin told reporters in February.

Protecting the bays isn’t enough on its own: they are fed by rivers and streams, which carry any potential pollutants from the peatlands they flow through. It’s all interconnected. And so a second piece protects the land, about 130,000 square kilometres of wetlands and 75,000 square kilometres of boreal forests in the boggy Hudson and James Bay Lowlands, which hold approximately 35 billion tonnes of carbon.

The council calls the overall project Omushkego Wahkohtowin. Omushkego refers to the people who have stewarded the land for generations. Wahkohtowin is a Cree word for relationships, the ways humans are interconnected with each other and the natural world.

“The Omushkego Wahkohtowin is a step that we can take to confront the challenges that our communities and our lands face, leading to a harmonious balance between economic development and protecting our natural environment,” Mushkegowuk Council Grand Chief Leo Friday wrote in the intro to the project’s draft conservation plan.

The plan says Omushkego Wahkohtowin may be implemented as a combination of different conservation tools. Provincial and national parks are an option, along with wildlife sanctuaries, wilderness areas and other possibilities to be determined by the nations involved. Most importantly, though, the council is trying to assure communities that Indigenous Rights and title will remain for the 15,000 Omushkego people living in the region — a concern at the forefront of many community members’ minds, even as they simultaneously worry about how mining and development could impact the landscape.

“I use the land, my dad uses the land, my uncles use the land,” Mushkegowuk Council Deputy Chief Natasha Martin told the group assembled in Kashechewan. “I want you to understand how passionate I am for the land and how important this project really is.”

The process is already markedly different from historical conservation projects in what’s now known as northern Ontario. When the provincial government created Polar Bear Provincial Park in the 1980s on the shore where Weenebeg and Washaybeyoh meet, it did little to no consultation with First Nations. Another project from the 1920s, the Chapleau Game Preserve, stripped Michipicoten and Brunswick House First Nations of their rights to hunt and harvest on 700,000 hectares of their traditional territories.

Indigenous people have been fighting for their rights to be recognized for over a century. In recent years, there’s finally global recognition that Indigenous stewardship is crucial to protecting nature and lowering carbon emissions. A growing list of precedent-setting Indigenous-led conservation projects reflect the importance of both rights and caretaking, and some have also merged sustainability with economic development. One is the Great Bear Rainforest in British Columbia, established in 2007 using same federal framework Mushkegowuk Council is now working to leverage. The original agreement for the Great Bear Rainforest included $120 million in funding from a mix of governments and private foundations — it has since generated nearly $300 million more in new investments, money used in part to “acquire, expand and create 123 local businesses,” according to the federal government.

An October 2023 explanatory document prepared by the Mushkegowuk Council said it will likely need to spend $660 million over the course of a decade. Of that, it expects $100 million to come from Parks Canada for the marine conservation project, $200 million from the federal Project Finance for Permanence program, and $50 million from philanthropy —the Wildlands League and Oceans North have also lent support. The remaining $310 million has yet to be secured. Eventually it will need revenue sources: one option is some form of tourism, done in accordance with Omushkego principles.

The vision, Martin says, is an economy with conservation at its centre. He says success will require an interconnected web of systems that ensures communities have the expertise, support and infrastructure they need to steward the land in accordance with their traditions, and are compensated fairly for it.

Indigenous Guardians — Omushkego people out on the land — would patrol and manage the land, and conduct research and monitoring. Martin wants to see Guardians in each Mushkegowuk community: a robust program including staff housing, other infrastructure, plus local post-secondary training in science and Traditional Knowledge. With food security being a continual problem, the plan also ties in traditional harvesting programs and plans for agriculture and greenhouses.

Mushkegowuk Council is also working on initiatives emphasizing the inherent connections between conservation and Omushkego culture. Land-based healing and detox programs are part of it. So is an existing council project, an artist collective called Oshichikesiwuk Nanipek, or those who create along the waters of the coast. Martin, a Juno Award winner who shredded onstage at the Kashechewan gathering in February, is part of the group.

“Being an artist, a lot of my inspiration is the land. I’m always paying attention, I’m always looking at it and the changes, learning how to read the land,” Christina Bekintis, a painter in the collective who also goes by Fire Wolf, said.

“It’s good to bring artists together with conservation and climate change … they’re really going to notice the changes to the land.”

Indigenous-led conservation is happening whether governments affirm it or not. That recognition, though, can go a long way in ensuring First Nations’ rights are respected and upheld under colonial laws as well as Indigenous ones. Often, it can mean agreements that define how industries like mining and logging are allowed to operate in the area.

To date, though, the Ontario government and industry have been pursuing a different vision for the economy here. One anchored by mining, specifically for critical minerals — highly sought-after materials needed to make fossil fuel-free technology like electric vehicles. Worldwide, companies and governments are scrambling to secure access to critical minerals and one place they’re looking at is an area of the Hudson Bay Lowlands called the Ring of Fire, where nickel deposits lie beneath the sensitive peatlands.

An October 2023 memo from Natural Resources Canada, obtained by The Narwhal through access to information legislation, internally flagged this potential clash of values. The department noted the “possible overlap of the Ring of Fire Eagle’s Nest project within the [Omushkego Wahkohtowin] area.” The Eagle’s Nest project is owned by Ring of Fire Metals, whose parent company is Wyloo Metals, a venture backed by Australian billionaire Andrew Forrest.

The final boundaries of the Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area aren’t set, so it’s unclear whether existing Ring of Fire mining claims will actually be a part of it. Martin says mining and conservation can co-exist — Omushkego Wahkohtowin would just define which land can be used for each.

“Mining companies we spoke to also agree with that. They need certainty,” Martin told reporters in February. “They need to know where conservation is and whatnot. So I think we can be headed in that direction, in the same lane.”

Mushkegowuk Council brought that messaging to a major mining industry conference in Toronto in April, with one staff member posing for photos in a shirt that read: “Conservation and critical minerals strategy working hand in hand.” Afterward, community members questioned the sentiment — Grand Chief Friday said the point was to tell mining companies that conservation has to be part of their plans.

“This is already happening in some Mushkegowuk communities. [Taykwa Tagamou Nation], the Chapleau Cree and Missinabee Cree are already involved in critical mineral extraction, and at the same time are backing conservation,” Friday wrote in a statement soon after the conference.

“Allowing critical mineral extraction on First Nations land is up to each individual First Nation and its members. The Mushkegowuk Council is not making that decision for them.”

The elephant in the room in all of this is Ontario. It’s not clear how Omushkego Wahkohtowin moves forward without the province’s involvement, given that Ontario claims jurisdiction over the land much of the proposal would cover. Premier Doug Ford’s government hasn’t exactly been enthusiastic about the idea of Indigenous-led conservation. In 2022, an internal provincial government document noted Ontario was concerned the federal government’s plans for Indigenous-led conservation were encroaching on provincial jurisdiction.

A handpicked provincial panel has also recommended Ontario pursue the concept, noting international consensus that lands managed by Indigenous Peoples contain about 80 per cent of the planet’s diminishing biodiversity. The provincial government mostly didn’t heed the advice. Ontario did agree to transfer land for the future Ojibway National Urban Park in Windsor, Ont., which will be co-managed by Parks Canada and at least one local First Nation. But it has also allowed a flood of mining claims inside Grassy Narrows First Nation’s Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area in northwestern Ontario, despite the nation’s move to forbid industrial activity there.

In Kashechewan in February, however, Martin told reporters he thought the province might be warming to the idea — particularly Ontario Indigenous Affairs Minister Greg Rickford. “He actually volunteered to be our champion,” Martin said.

When The Narwhal asked Rickford about Martin’s comments a couple of weeks later, the minister said he’s open to it.

“We’ve taken a preliminary look at what they’re proposing,” the minister said.

“We’d like to try to understand a little bit more about it, but we want to ensure that all First Nations communities’ interests are aligned … the Government of Ontario has a keen interest in legacy infrastructure, prosperous communities, which very much includes First Nations communities.”

Wyloo spokesperson Leanne Franco declined to comment since the boundaries of the area to be conserved aren’t final. Juno Corp., another mining company with mineral holdings in the Ring of Fire, didn’t answer a request for comment.

The project is moving forward in the face of a whole undercurrent of worries — concerns about whether the federal government can be trusted, whether youth and elders are being properly consulted, whether colonial laws can be used to heal colonial damage and even if this whole thing might be too big to pull off.

For the better part of a week in February, representatives from all nine of the communities involved — Attawapiskat, Chapleau Cree, Fort Albany, Kashechewan Cree, Missanabie Cree, Moose Cree, Weenusk and Fort Severn First Nations, along with Taykwa Tagamou Nation — gathered with guests in Kashechewan. Inside the community’s high school, a bustling kitchen served moose stew topped with bannock, burgers, goose and carafe after carafe of coffee and Labrador tea. Inside the gymnasium, people from the communities filled rows of plastic chairs while officials took turns at the microphone to herald the milestone of the day, the approval of the marine conservation project’s feasibility study.

More than once, the joy of how far the project had come was tempered by questions about what happens next.

“I urge all young people to be careful of what you agree to,” Madeline Scott, a councillor at Fort Albany First Nation, said.

“I urge the leaders, be careful what you are going to agree to.”

On the celebration’s final night, Martin stood on the side of the room, mind racing, already trying to figure out how to take what he’d heard and fold it into the next phase of Omushkego Wahkohtowin. How to make the plan better, how to get more people who were skeptical or scared on board. The coming months, he was set to tour the communities participating in the project to update them on their progress, to hear more feedback and incorporate it into whatever happens next.

“Let’s work together,” he had urged them a few moments earlier, in his closing remarks for the night. “Protect our lands, protect our waters.”

Updated April 26, 2024 at 9:54 a.m. ET: This article was updated to correct the spelling of Christina Bekintis.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On March 17, federal Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre...

Continue reading

B.C. previously allowed mineral claims without First Nations consultation. It was court-ordered to fulfill its...

British Columbia has vowed to fast-track several mining projects in an effort to blunt the...

Alberta introduced North America’s first industrial carbon tax in 2007. Now an industry email obtained...