The Narwhal picks up National Magazine Award nomination for Amber Bracken’s oilsands photojournalism

Bracken was recognized for intimate portraits of residents of Fort Chipewyan, Alta., who told her...

This is part three of a three-part series on Wood Buffalo National Park featuring photos by Louis Bockner, Sierra Club BC. Find the first story here and the second story here.

When Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation elder Alice Rigney gazes at the Peace-Athabasca Delta, which has sustained her family for generations, she remembers the whitefish she and her brother caught several years ago in Jackfish Lake.

The fish was cooked in the traditional way, over an open fire, but, unknown to Rigney, there had been an upstream oil spill.

“The fat dripping from it was black,” she said.

Rigney believes the delta and Wood Buffalo National Park have been changed beyond repair by the oil industry and dropping water levels. So she is struggling to understand a proposal by Indigenous leaders to buy a section of the Trans Mountain pipeline, recently purchased by the federal government from Kinder Morgan.

Like many others in Fort Chipewyan, a tiny Alberta hamlet on the banks of Lake Athabasca, Rigney is conflicted because oil money forever changes the live-off-the-land lifestyle — and she blames governments and the oil industry for beating down Indigenous opposition to oilsands projects to the point that buying in seems the only option.

“I could not believe that my community wants to be part of this pipeline. They have forced us into a corner where we have nowhere else to turn,” Rigney said sadly.

“Just think 100 years from now what this planet will look like. They are destroying the land.”

All photos by Louis Bockner/Sierra Club BC

Robert Grandjambe checks his nets on Lake Athabasca, Fort Chipewyan, Alta.

Lake trout hauled from Lake Athabasca.

Anger at environmental damage, fears of health problems and apprehension about disappearing culture compete with modern reality and economic pragmatism as Indigenous leaders struggle to decide where the future lies.

In Fort Chipewyan, where many young people take fly-in-fly-out shifts in the oilsands, a new affluence is taking hold and traditional activities, such as a moose-hide tanning workshops, are failing to attract participants.

Worker housing in Alberta’s oilsands.

A sense of resignation is washing over Indigenous communities with the realization that, after decades of submissions to environmental assessment hearings, expensive court cases and negotiations, almost all of the more than 170 oilsands projects have been approved despite Indigenous objections.

“Even when communities are consulted and raise concerns and rights violations, projects are still approved despite admissions of irreversible and adverse impacts on the people and the land,” said Eriel Deranger, a member the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation and executive director of Indigenous Climate Action.

“This can destroy the spirit of the people.”

The result is a flurry of meetings and carefully worded memos, with companies courting Indigenous support and leaders walking a precarious tightrope, hoping a seat at the table will offer environmental and economic benefits.

The ambivalence is underlined by last month’s surprise statement from Athabasca Tribal Council — whose five members include Mikisew Cree and Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation — that they are considering buying a piece of the pipeline. The proposed purchase has not yet been ratified by the communities.

For pipeline opponents it was a shock that the move was announced by Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation Chief Allan Adam, president of the Athabasca Tribal Council, whose history as a prominent opponent of oilsands projects includes campaigning alongside celebrities such as Jane Fonda and Leonardo DiCaprio.

Mikisew Cree Chief Archie Waquan told The Narwhal he believes he has to modernize the economy for the sake of the younger generation.

“Do we remain the same and be ‘anti-’ or get on the boat and deal with industry and be able to be part of what is happening there? I look at what is happening south of us in the tarpits and the oilsands and, if we don’t partake in it, we will be left behind and I will be to blame,” he said.

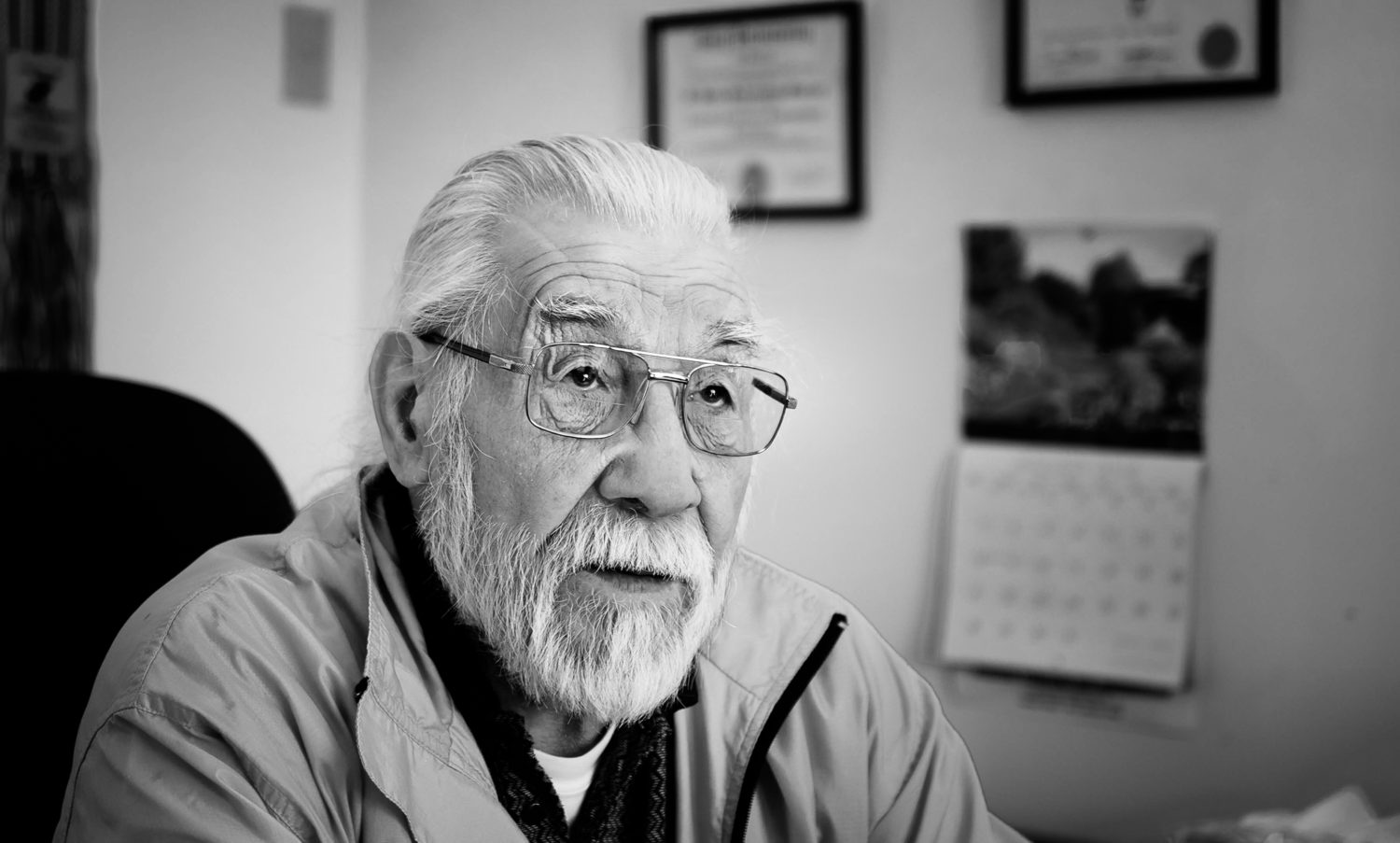

Mikisew Cree Chief Archie Waquan in Fort Chipewyan, Alta.

A playground in Fort Chipewyan overlooking Lake Athabasca.

A hunter’s cabin near the border of Wood Buffalo National Park in the Peace Athabasca delta.

A river snakes through Wood Buffalo National Park.

It is not the first foray into the industry for Mikisew Cree who, last year, together with Fort McKay First Nation, bought a 49 per cent interest in a Suncor Energy storage facility.

A pipeline share is a logical next step, Waquan said, acknowledging there are continuing concerns about industry pollution and water withdrawals, but emphasizing that a seat at the table will help put controls in place.

“I have to look to the future beyond my time here on earth. Times have changed and we have to realize that. We need to go to a modern lifestyle, which I think my First Nation wants and that means we have to deal with industry. We have to keep them in check,” he said.

“You can’t reverse it now, but in time, when all the development is gone from this territory, our land will always come back to where it used to be. It is resilient in a sense,” Waquan said.

However, other oilsands projects go beyond any contemplation of support and both Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation and Mikisew Cree oppose the massive Teck Frontier project proposed for a site only 30 kilometres south of Wood Buffalo National Park.

The Alberta oilsands meet the boreal forest. Teck is currently proposing to build the Frontier mine, which would become the largest oilsands mine to date.

Ironically, it is likely the Trans Mountain pipeline would transport oil from the Teck development, although Teck spokesman Chris Stannell said that, if the project is approved, the first oil is not expected to flow until 2026, so shipping plans have not yet been determined.

Stannell said the company has signed agreements with 11 Indigenous groups, which include “economic and social benefits and opportunities.” That support includes Fort Chipewyan Metis Local 125, which has signed a participatory agreement with Teck in return for economic benefits and opportunities to negotiate traditional land use and environmental stewardship.

Proposed site of Teck’s Frontier mine 30 kilometres south of Wood Buffalo National Park.

Proposed site of Teck’s Frontier Mine 30 km south of Wood Buffalo National Park. If built it would be the largest mine ever constructed in Alberta’s oilsands.

Alberta’s oilsands north of Fort McMurray.

The $20 billion Teck project, which will advance to federal-provincial review panel hearings this fall, would be the oilsands’ largest open pit mine, covering 292 square kilometres, producing 260,000 barrels of oil a day over 40 years and, according to the company, providing 7,000 construction jobs and 2,500 jobs once the project is operational.

Among the many objections to Teck Frontier, the proximity to the Wood Buffalo National Park boundary is likely to prove a major hurdle.

A petition from Mikisew Cree sparked a UNESCO investigation into threats to the World Heritage Site and the United Nations agency concluded last year that Wood Buffalo is facing threats from energy development, hydro dams and poor management. UNESCO has given Canada an ultimatum to come up with an action plan by the end of the year or risk the park being added to the list of World Heritage Sites in Danger.

On Thursday, Minister of Environment and Climate Change Catherine McKenna announced $27.5 million in funding over five years to support the development of an action plan for Wood Buffalo National Park World Heritage Site.

Map of threats to Wood Buffalo National Park from UNESCO report.

Both Mikisew Cree and Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation are preparing their cases for the Teck hearings, but, in the meantime, are negotiating with the company on concerns such as buffer zones and protections for bison and caribou.

“We have to protect the wildlife that is there and the development is getting too close to the area we are trying to protect through UNESCO,” Waquan said.

The question of how to deal with projects such as Teck is complicated, especially given the history of developments being approved despite Indigenous concerns, said Matt Hulse, Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation regulatory affairs coordinator.

“There’s a lot of grey. Everyone realizes the jobs are down there (in the oilsands) and that’s where the money comes from. People don’t want the (Teck Frontier) mine to go ahead, but, because we have so little confidence in regulatory process, Indigenous communities are forced to find ways to benefit from the project to offset the impacts. There isn’t any good option,” Hulse said.

Teck Frontier would be built on key habitat for caribou and the Ronald Lake bison herd, the only disease-free, genetically pure wood bison herd in the area.

“Because we have so little confidence in regulatory process, Indigenous communities are forced to find ways to benefit from the project to offset the impacts. There isn’t any good option.” — Matt Hulse, Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation regulatory affairs coordinator

Rivers will be diverted and wood bison and caribou herds will be destroyed, said elder Roy Ladouceur, who lives at Poplar Point Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation reserve, 16 kilometres from the Teck site.

“They say they will find ways of preserving the habitat, but I just can’t see it happening. No way and no how. They say they can relocate the animals — you can’t do that to any animal. You are breaking nature’s law. It’s not their home,” he said.

“You can’t seem to make the scientists and environmentalists understand. You can’t break nature’s law.”

Stannell said Teck recognizes the importance of the Ronald Lake bison herd to Indigenous communities and the Frontier project will include “comprehensive bison mitigation and monitoring actions, developed in consultation with indigenous communities, government and stakeholders.”

The project also includes environmental mitigation including a storage pond allowing water withdrawals from the river to be halted during low flow periods, he said in an e-mailed response to questions.

Deranger, an Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation member who worked closely with Chief Allan Adam for six years as he lobbied against oilsands developments said she has watched industry and government wear down Indigenous opposition.

Economic benefits agreements, with companies promising to transfer millions of dollars to First Nations, amount to bribes, Deranger said.

“The way we are allowing this to happen is absurd,” she said.

“This is the next chapter of neo-colonialism. . . . They are saying in order for you to survive in the economic system we have imposed on you, you have to join us. There’s no choice any more. The rights of industry and corporations have taken precedence over Indigenous rights.”

The system is stacked against First Nations who have fought projects all the way through the courts, spending millions of dollars and years of research time, only to be told their rights don’t matter, Deranger said.

“There’s no choice any more. The rights of industry and corporations have taken precedence over Indigenous rights.” — Eriel Deranger, executive director of Indigenous Climate Action

And those losses have taken a toll.

“I wouldn’t say it has divided our communities. I would say people are worried about the economic future and they have lost sight of the cultural future because of their economic needs,” she said.

There is a strong case against the Teck proposal because of the obvious effects on bison, caribou, water and air, Deranger said.

“I want to say that there is absolutely no way in hell this government could approve this project, but I just don’t know,” she said.

Now, an additional concern is government ownership of the pipeline, Deranger said.

“Kinder Morgan hadn’t even secured enough oil to flow through it from operators in the tar sands and they haven’t secured a buyers’ market at the other end, so my concern is (government) would want to approve this project because it would secure a substantial amount of oil to flow through the pipeline.”

Within the communities there are mixed feelings about deals with oil companies, with recurring concerns about lack of information from First Nation leaders and companies.

“Teck should be giving information to the members because they are the ones out there fishing and hunting every day,” said Jocelyn Marten, Mikisew Cree community coordinator, pointing out that it has been four years since company representatives met the members.

Smith’s Landing, on the north side of Wood Buffalo, is on Teck’s list of First Nations consulted, but the band’s lands and resources manager Becky Kostka said there has been no meaningful consultation.

“We are deeply concerned about the Teck project and the impact on Wood Buffalo National Park. It’s too big and too close to the park,” she said.

For Robert Grandejambe, the information gap lies with the lack of Mikisew Cree membership meetings, especially in light of the pipeline purchase plan.

“The community is already getting shut-up money from the oil industry. They should be telling them to put that money into protecting the environment,” he said as he hauled in fish from Lake Athabasca to feed his sled dogs.

Others, such as Rigney, believe it is already too late to protect the environment from oilsands ravages.

“I just wish this river flowed south so all the people in Edmonton and Calgary would get this shit instead of us,” she said.

The Narwhal’s reporter Judith Lavoie travelled with Sierra Club BC campaigner Galen Armstrong and Sierra Club BC photographer Louis Bockner to Wood Buffalo National Park in early June. Lavoie’s travel expenses were paid by The Narwhal, with the exception of a flyover of a section of Wood Buffalo National Park, for which she snagged an empty seat in the plane.