Bill 5: a guide to Ontario’s spring 2025 development and mining legislation

The public has a few days left to comment on Doug Ford’s omnibus development bill....

A flurry of new requests to build on Ontario’s Greenbelt is stoking fears that the province has opened the floodgates for developers to chip away at protected areas around Toronto.

At least four landowners have asked to build on the Greenbelt since the province opened up 7,400 acres of the protected area for development last year, according to postings on Ontario’s environmental registry. Municipal Affairs and Housing Minister Steve Clark is staying mum on whether he will grant these requests.

Three of those landowners are developers — Marshall Homes, White Owl Properties and 1628755 Ontario Limited, which is run by the Durham-based Lysyk family — while the fourth is a church in Markham.

When Clark announced plans to open the Greenbelt in November, critics and environmentalists warned the change would clear a path for more developers to build more on the protected area. The minister’s office did not acknowledge a detailed list of questions from The Narwhal, including one about whether Clark had plans to approve future removal requests.

Victor Doyle, a former provincial planner credited as an architect of the Greenbelt says the new requests are a “bad omen going forward.”

“It really reinforces the fact that the government’s willingness to remove land from the Greenbelt is stimulating thinking amongst other landowners to seek the same treatment,” Doyle said.

“That type of speculation is completely contrary to the Greenbelt and undermines the certainty that its protection in perpetuity was intended to provide.”

Max Lysyk, the development manager for 1628755 Ontario Limited, said in his family’s case, their request isn’t motivated by greed or a dislike of the Greenbelt — they just believe part of their property was included in it by mistake. They agree that one forested, marshy area on the land should be protected. But the property’s northeast corner is a slice of farmland they say is indistinguishable from non-Greenbelt farmland directly south of the protected area’s boundary.

“They just drew a line completely across running from west to east, whereas they should have done a little bit more research or at least spoken with us,” Lysyk said of the original formation of the Greenbelt.

“We would have happily taken them on a tour and explained what we’ve felt is a proper delineation of the Greenbelt.”

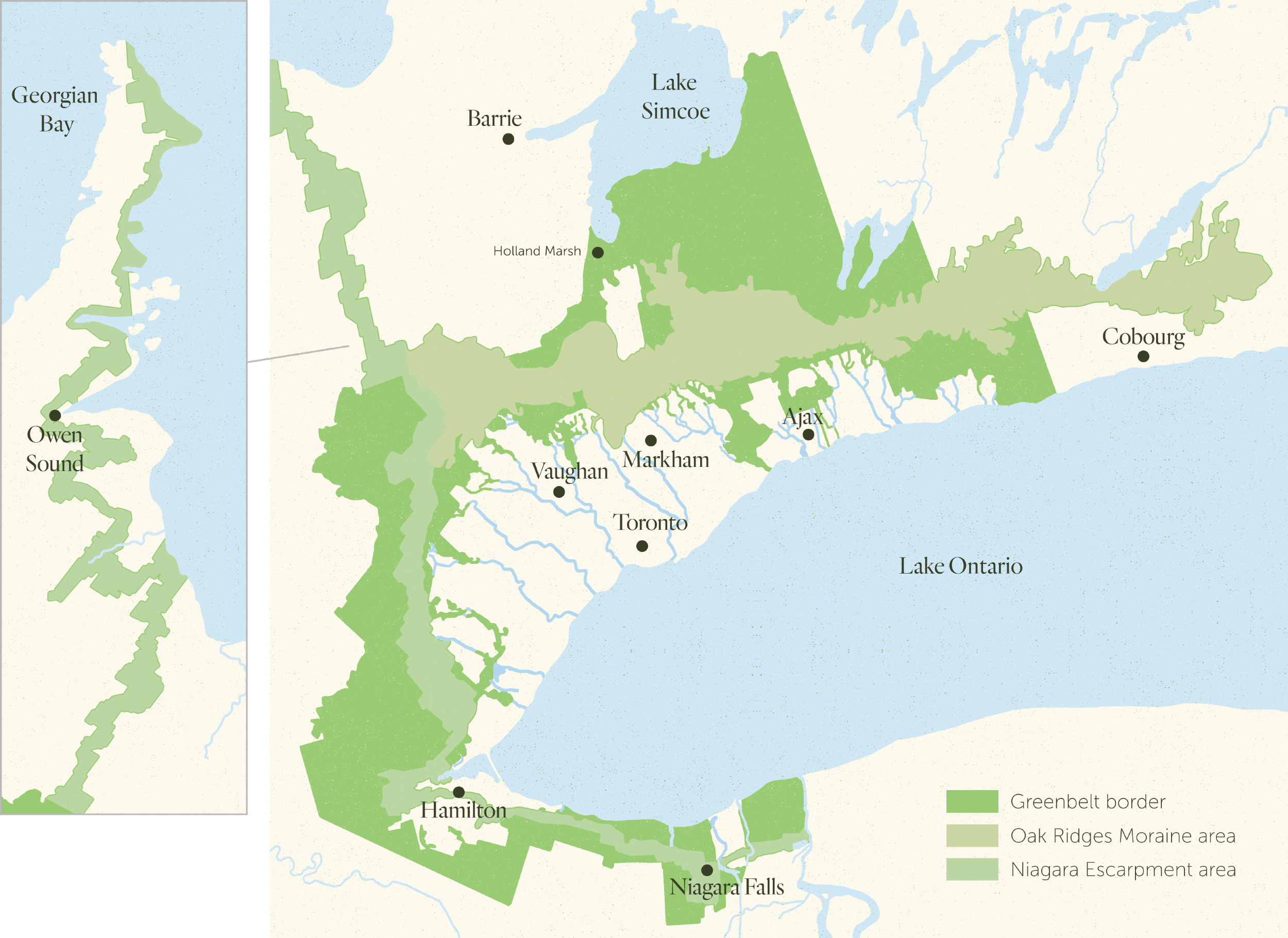

Requests to remove land from the Greenbelt are nothing new. The Ontario government created it in 2005, with the intent of permanently protecting a swathe of prime farmland, forests, wetlands, creeks and river valleys that encircle the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area. From the beginning, the concept was controversial to some land speculators, who bought up cheap farmland near cities, expecting its value would go up as the suburbs expanded outwards. Other landowners have long argued that the boundaries of the Greenbelt included some plots of land by mistake. For a long time, however, successive governments mostly refused to entertain requests to allow development in the Greenbelt.

In 2016, the Liberal government under Kathleen Wynne did a scheduled review of the protected zone’s boundaries and received hundreds of requests to remove land from it. In the end, the Liberals removed 370 acres of land from the Greenbelt in 17 areas, a series of small adjustments that did not prompt outcry from environmentalists. (One, for example, corrected a case where half of a commercial building was in the Greenbelt and half wasn’t.)

Premier Doug Ford himself promised for years that he wouldn’t open the Greenbelt. At an event in 2018, before he entered provincial politics he pitched the idea of allowing developers to build on it, but he retracted the idea after swift, strong public backlash.

“People don’t want me touching the Greenbelt, we won’t touch the Greenbelt,” Ford said at the time.

But when Ford reversed that position in November, he said opening the Greenbelt would allow the construction of 50,000 new homes — a move the government’s own housing task force said was unnecessary to solve Ontario’s housing crisis.

Soon after the government announced the Greenbelt changes, The Narwhal and The Toronto Star published a joint investigation revealing that six developers bought Greenbelt land now slated for development in the years since Ford was elected in 2018. Other developers who have owned portions of the Greenbelt for many years now stand to see the value of their land skyrocket. The investigation also showed that several of the developers who stand to benefit most donated significant sums to Ford’s Progressive Conservatives. Some also hired Tory-connected lobbyists to speak to the government on their behalf. None of the new requests to open Greenbelt land reviewed by The Narwhal were sent by developers included in the Narwhal/Star investigation.

The cuts to the Greenbelt are currently under investigation by two provincial watchdogs. The Ontario Provincial Police are also mulling whether to launch a third probe.

“What the government has done here is send a clear signal to the real estate industry and the development industry that the Greenbelt isn’t permanent, and if they talk to the right people, and they go to the right parties, that they may be able to have their land removed from the Greenbelt as well,” Tim Gray, the executive director of the charity Environmental Defence, said.

Though the province has said it will return the lands to the Greenbelt if housing development hasn’t begun by 2025, the regulation it used to finalize the changes doesn’t mention this, or include a mechanism to make it happen. Clark’s office didn’t answer when asked how the government can guarantee it will keep its promise. Senior planning staff in at least three municipalities have said it would be difficult to meet Ontario’s 2025 deadline.

The landowners who made requests to develop additional Greenbelt land through the Environmental Registry did so in response to the original proposal to open 7,400 acres. Under Ontario’s Environmental Bill of Rights, governments are required to post proposals affecting the environment on the registry, and give the public 30 days to send feedback. It’s not common for landowners to make requests to remove land from the Greenbelt through the Environmental Registry, which is public — more often, requests like that would be sent directly to the minister or through lobbyists, often out of the public eye.

Clark’s office didn’t answer when asked whether he’s received any more requests to open Greenbelt land through other methods.

In their comments on the idea of allowing development on some parts of the Greenbelt, the four landowners said the government should also consider opening up their land. Several argued that their properties should not have been included in the Greenbelt in the first place.

The original boundaries of the Greenbelt took years to sort out. Landowners had the chance to correct any perceived errors when the previous government did a review between 2015 and 2017, the process that led to those 17 changes, said Ed McDonnell, CEO of the Greenbelt Foundation, the charity that stewards the protected area.

“It may not always be obvious why the lines are where the lines are, but this is the subject of years of consultation prior to the creation of the Greenbelt, and a multi-year process at the [2017] review to assess the boundaries,” McDonnell said.

“These are boundaries that are aligned with important natural features.”

Max Lysyk, the development manager for 1628755 Ontario Limited, said his family accidentally missed the opportunity to get the Greenbelt boundary adjusted in 2017. The family hasn’t heard anything back from the province since submitting their request last year, and Lysyk said he’s assuming it won’t be granted.

“I’m not saying to cut down all the Greenbelt and just build houses,” he said. “But there were mistakes that were done.”

Lysyk told The Narwhal his family is working on an application to build houses on the southern, non-Greenbelt part of the property, which includes plans to plant trees on the edge of the protected area. If building is allowed, the site could host 52 to 55 single-family homes, Lysyk’s submission to the province said.

Two other requests to remove land from the Greenbelt came from developer Marshall Homes: one in Ajax and one in Courtice, both communities east of Toronto. The properties in both areas are close to municipal services and existing development, Marshall Homes said in its requests — two criteria the province has said it used last year when deciding which parcels of Greenbelt land to develop.

The land in Courtice also includes wetlands and other natural features, according to a provincial map of the Greenbelt. It’s adjacent to another section of land the province removed from the Greenbelt in December. Company president Craig Marshall didn’t answer questions about the requests from The Narwhal.

White Owl Properties, meanwhile, asked to develop about 160 acres of Greenbelt land in Richmond Hill that’s also in the Oak Ridges Moraine area north of Toronto. Legislation protecting the Oak Ridges Moraine, a 160-kilometre rocky ridge, is older than the Greenbelt itself, and those rules map out where development is and is not allowed. In its letter posted to the Environmental Registry, White Owl said it isn’t asking Clark to remove the company’s land from the Greenbelt, but to change how it’s categorized under the Oak Ridges Moraine Conservation Act.

“We believe that the [site] offers an excellent and ideal opportunity for the province to expand the lands available for residential use within the Greater Toronto Area without the controversy associated with removal of lands from the Greenbelt,” White Owl Properties president Larry Repar wrote in a letter to Clark. The province’s Greenbelt map shows wetlands, a waterway and other natural features on the site.

White Owl Properties is part of a larger company, the White Owl Family Office Group, which didn’t respond to questions from The Narwhal. It manages assets held by the Carrick and McArthur families, who are involved in various Ontario construction companies. The company’s land on the Oak Ridges Moraine is bordered by residential areas on two sides and includes a golf course, a municipal compost facility and an asphalt plant. The site also has a permit for a quarry to extract aggregate, the rocks and crushed stone used to make concrete, but hasn’t used it — the permit was grandfathered in when the Oak Ridges Moraine was protected.

White Owl’s proposal to build on the land includes 1,000 to 2,000 low or medium density residences, a school, a park and a commercial area. In exchange, the company offered to set aside another 720 acres it owns elsewhere on the Oak Ridges Moraine — where development already isn’t allowed — for conservation.

“Assuming this is of interest to the government, White Owl is proposing to either donate these lands for conservation purposes to an organization such as the Nature Conservancy or to make them subject to a conservation easement,” Repar wrote.

The People’s Gospel Church in Markham, Ont. also argued that land it owns was included in the Greenbelt by mistake. The overall lot is nearly 13 acres, but the portion of it next to the road is included in the Greenbelt. It’s part of a Greenbelt ‘finger’ — a portion of protected land that follows the path of a watershed, named for how they look on a map — that follows Robinson Creek and encompasses wetlands, the province’s map shows.

Because the property is surrounded on its other three sides by land owned by other people, there’s currently no way for the church to build a road to access the property, which it said it hopes to use to build a “worship place and community facilities,” according to a presentation the church submitted through the environmental registry.

“Community facilities will also be needed when more houses are built,” the presentation said. The People’s Gospel Church didn’t respond to questions from The Narwhal.

Not everyone understands the importance of the Greenbelt in certain areas, McDonnell said. Greenbelt fingers might look random on a map, but they intentionally follow meandering waterways and natural features on the landscape, which don’t adhere to property lines. And removing agricultural land in the Greenbelt can have long-term consequences for surrounding farms and long-term food production.

“The permanence of the Greenbelt is what has made it an international success story,” McDonnell said.

“Those underlying systems — agricultural, natural and water systems — are what the Greenbelt is intended to protect, and it provides the basis for its success. We need to maintain the idea of permanence to maintain the idea of long term protection for the Greenbelt to continue to be successful as it has been.”

When the Ontario government removed 7,400 acres from the Greenbelt, the plan involved a land swap — it also added 9,400 acres to the Greenbelt elsewhere. Some of that land came from a series of urban river valleys that weren’t developable anyway, but most of it is along a ridge called the Paris-Galt Moraine, located in the Town of Erin, northwest of Toronto.

Erin — and Wellington County, which Erin is a part of — are now asking the Ontario government to take other land out of the Greenbelt nearby. In a letter to Clark, Wellington and Erin said the government’s Greenbelt expansion on the Paris-Galt Moraine is “unnecessary,” as other local plans and policies already protect the area. But with the province pushing forward with that plan, the county and the town asked Clark to also remove about 400 acres of land from the Greenbelt on the edge of Erin’s boundary, which it said the community would need to accommodate future growth.

The letter noted that the town needs 60 acres more land to meet its growth targets, a number it came up with through Ontario’s controversial urban planning process. It did not explain why, then, the town is asking the province to remove nearly 400 acres, a far larger area.

Jack Krubnik, the director of planning and development, said in an email that the town wants more “employment land,” or land set aside for businesses and other economic activity, to support existing and new jobs as Erin’s population grows.

“The town’s current employment lands are geographically limited within the Erin Urban Area, which is surrounded by the Greenbelt,” Krubnik wrote. “This restricts the ability for the town to expand its employment base.”

In the meantime, environmentalists say they’re watching for sales of Greenbelt land as developers push to open up more of the protected zone.

One property in the Greenbelt in East Gwillimbury, north of Toronto, went up for sale in mid-November. Though the land is currently protected and cannot be used for urban development, an online listing for the property says it’s “for not so far in the future, development.” Its asking price is just under $4.4 million for 50 acres, which includes a house and equestrian centre.

The listing agent, Michelle Timoski-D’Amico, didn’t answer questions from The Narwhal.

Doyle said a rush of speculation on the Greenbelt raises the risk that the edges of the Greenbelt will be gradually whittled away. Even if the province continues to add land elsewhere to compensate for losses, the Greenbelt could gradually migrate away from the Greater Toronto Area, where there’s already not much green space left to sustain farming and prevent flooding.

“Over a matter of time, the Greenbelt won’t be where it was initially planned to be,” Doyle said.

“And the lands, farmland and natural features that [the Greenbelt] was originally intended to protect will no longer be protected.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

The public has a few days left to comment on Doug Ford’s omnibus development bill....

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits

Climate change, geopolitics and business opportunities power a blue economy