Two blank cheques: are Ontario and B.C. copying the homework?

Governments of the two provinces have eerily similar plans to give themselves new powers to...

Days after upending urban development rules for the third time since October, the Ontario government threw another curveball at six municipalities, forcing at least four to sprawl outward.

The province’s changes are seen in significant edits to policy documents called official plans, which define where and how cities can grow, posted late Tuesday evening. The exact impact of the changes wasn’t immediately clear Thursday as municipal staff in the communities — Waterloo Region, Belleville, Barrie, Peterborough, Guelph and Wellington County — scrambled to figure out the implications.

Premier Doug Ford’s Progressive Conservatives ordered Waterloo Region, Wellington County, Belleville and Peterborough to push their urban boundaries further outward than local planners had wanted and allow more sprawl. The move is similar to what the provincial government did to the City of Hamilton and Halton Region last fall, when it overrode both municipalities’ wishes and forced them to allow development on prime farmland.

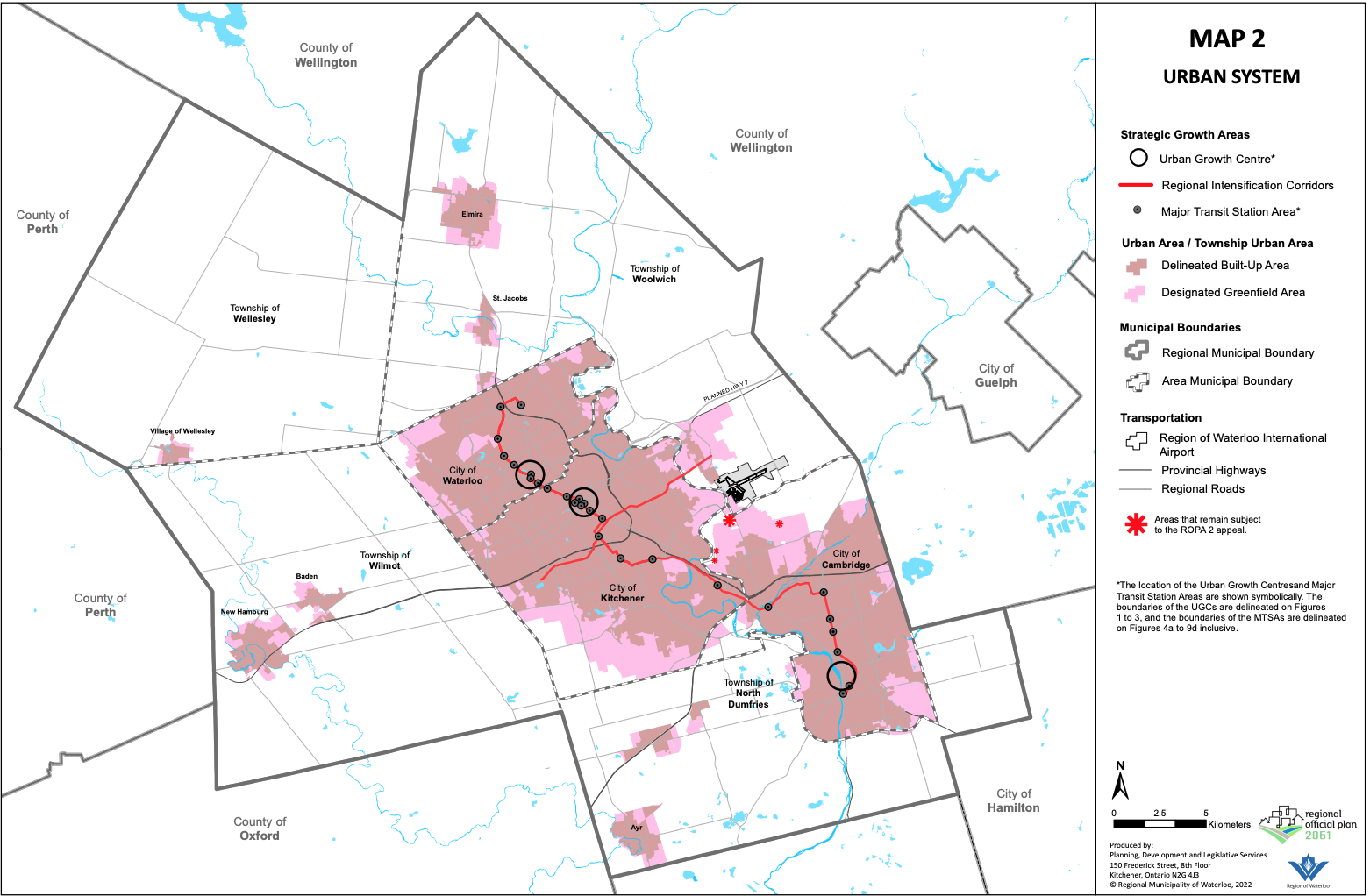

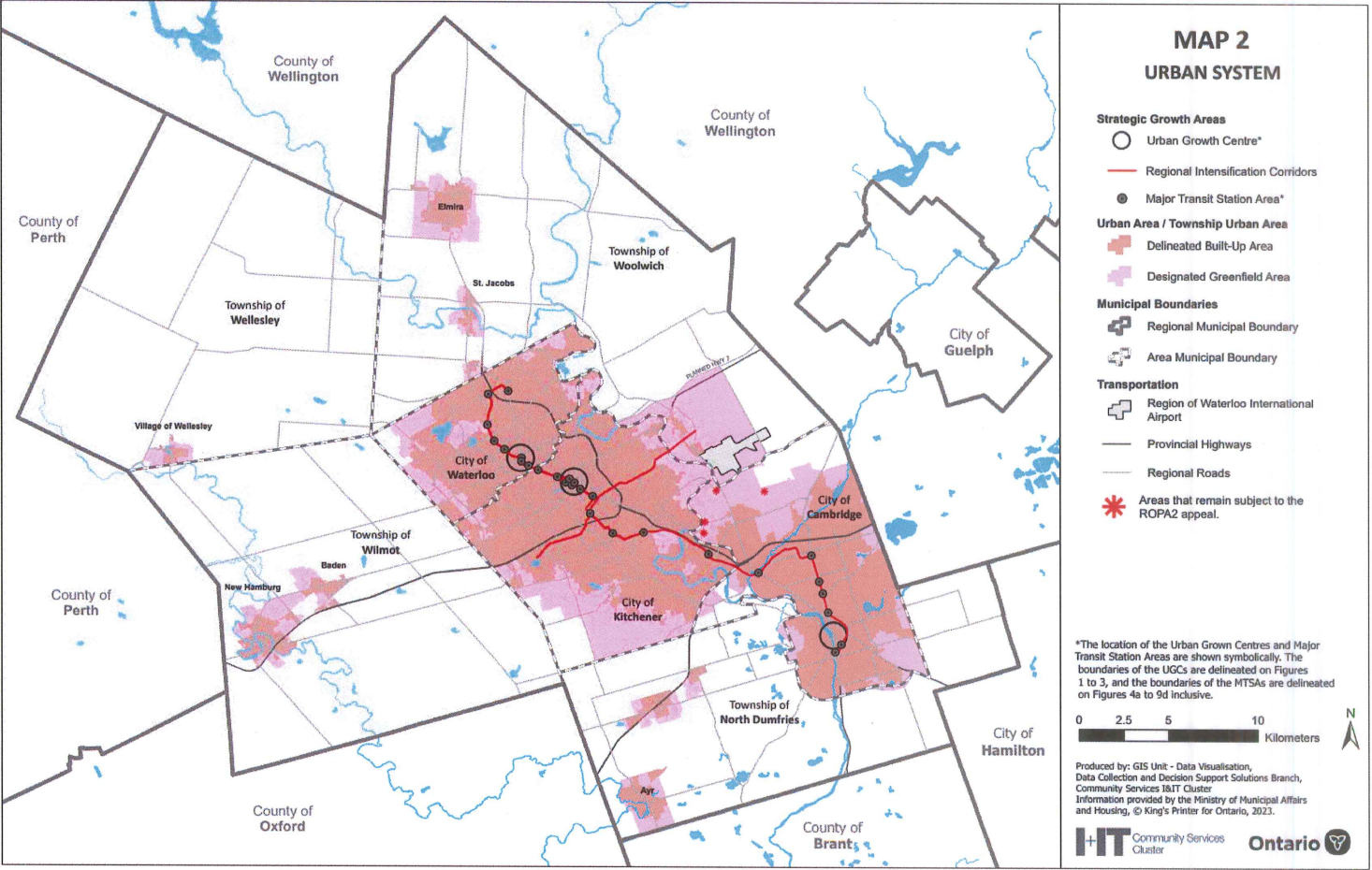

The exact scale of the expansion wasn’t immediately clear. The acreage wasn’t spelled out in the new official plans, but visual comparisons of the province’s final maps and the ones proposed by the municipalities show significantly more land set aside for future development.

The province also changed a single but significant word in multiple plans, by which it seemed to water down regulations that would encourage municipalities to mandate density and affordable housing. “Shall” or “will” has been changed to “should” in many instances across all six municipal plans, meaning that once-codified requirements are now mere suggestions. For example, in a line that previously read “Infrastructure will also incorporate winter-city design elements,” the word “will” has been crossed out and replaced with “should.”

Ontario’s Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing, which oversees municipal plans, did not respond to multiple requests for comment from The Narwhal.

Phil Pothen, Ontario program manager with the charity Environmental Defence, said urban sprawl in Waterloo and Wellington are particularly concerning because it would eat up green space in a region where biodiversity is already under serious threat. Much of Ontario’s quality agricultural land is clustered there, and the area is home to a multitude of species that can’t survive further north.

One Waterloo region planning official who wasn’t authorized to speak publicly told The Narwhal the provincial government has opened upwards of 2,000 hectares (over 4,900 acres) of green space and farmland to development.

“In those areas, most of the habitat has already been lost,” Pothen said. “The patches of habitat that remain are very sensitive to features like sprawl, and sprawl is probably the biggest threat to them.”

Urban sprawl, or the uncontrolled expansion of city development, is also bad for the environment in other ways. It increases dependency on cars, which emit carbon and other types of pollution. Green space also naturally absorbs water to mitigate floods and sequesters carbon, capabilities that are lost when it’s paved over. These are some of the reasons dense communities centered around transit are generally seen as a more ecologically sustainable option.

The changes came via the Ford government’s now-cemented playbook: highly technical documents sent to municipalities late in the day and posted on the Environmental Registry of Ontario — the database the government is legally required to share changes to environment and energy policy for public feedback and consumption — without notice. All six approved plans come with the same four-word note attached: “Appeals are not allowed.”

Andrea Ravensdale, a spokesperson for Wellington County, said planning staff there hadn’t yet had time to digest the changes.

In Guelph, city staff didn’t believe the edits to their official plan would result in urban expansion, said Melissa Aldunate, the city’s manager of policy planning. City staff in Barrie are still reviewing the modifications to their plans, but so far they appear minor, spokesperson Scott LaMantia said.

Though the Ontario government hasn’t publicly commented on the changes to the municipalities’ official plans yet, it has said as recently as last week that its sweeping changes to Ontario’s urban planning rules are aimed at tackling the province’s housing crisis. More homes are needed in the province, but critics have questioned whether the onslaught of changes the Ford government has introduced in the past six months will deliver the type of housing Ontarians need, and anytime soon. Last December, Ontario’s own Housing Affordability Task Force released a detailed report identifying zoning, not land availability, as the number one issue.

The Ford government’s edits to official plans in some cases removed mandates for affordable housing. Last week, it also announced plans to lower density targets.

The government’s changes to the official plans also override years of work and consultation by the municipalities themselves, which spent years developing official plans following rules handed down by the Ford government that have now been rewritten. With the laws and rules constantly shifting, municipal planners have barely had time to catch their breath.

“Maybe we need to put a bit of a pause [on these policies] and allow these changes to work their way through the system before we start making other large, system-wide changes,” Steve Robichaud, Hamilton’s chief planner, said last week after other changes were announced.

It’s unusual for a provincial government to make such “extreme” edits to local development plans, Pothen said. “The types of edits that have been added … are really, completely the opposite direction that you’d expect a government to be implementing.”

Ontario Green Party Leader Mike Schreiner pointed out that sprawling development often leads to higher costs for municipalities, which have to build more expensive roads and water mains in neighbourhoods that are spread out. And more costs are a big ask given that other Ontario government changes from last fall reduced the fees that developers pay municipal governments.

“Municipalities just can’t afford, like literally cannot financially afford, the Ford government imposing an expensive sprawl agenda on them,” Schreiner said.

Up until now, Waterloo Region has been known for setting the bar on urban density in Ontario and beyond. In 2009, it implemented a fixed border between rural and urban areas intended to be impermeable to development pressures. The region also mandated a dense urban environment that was connected to active transportation, including bike lanes and light-rail transit.

The region’s growth plan was groundbreaking and unprecedented, winning awards across North America, and lauded for being collaborative, with great input from community and developers alike. Waterloo Region’s strict country line remained intact even as its emerging tech industry grew and the region became a place where both Google and agriculture could thrive. It was so successful that it inspired the province’s first growth plan in 2006.

Last June, the region adopted a 30-year roadmap that would implement high-density, walkable neighbourhoods with 60 per cent of new growth in already built-up areas, and additional protection of the countryside line. The plan was supported by Six Nations of the Grand River, on whose unceded territory the region is located, and met the province’s designated growth targets.

A lot of that is now irrelevant. While the government didn’t significantly change the density targets set by the region, it did accelerate the opening up of much rural and agricultural land to development. A lot of this land would have been opened up slowly and, hopefully, sustainably over the next 50 years: it seems, though, the provincial government wants them developed now, despite the lack of sewage, energy and water infrastructure imperative to residential housing.

“I am surprised,” Kevin Eby, a former Region of Waterloo director of planning until 2015, told The Narwhal. “We in Waterloo had clearly demonstrated we had a plan that was working. There was no indication that we were failing … We were accomplishing everything that the provincial rules wanted us to accomplish. Why then would they come and override us?”

Eby said the province’s decision has likely opened Waterloo to 200,000 more people than its 2051 population forecast, without offering local planners any data to confirm the region can handle that level of population increase. The region is the largest municipality in North America that uses groundwater as its main source of drinking water, relying mostly on the Grand River and aquifers in the surrounding moraines.

“I don’t know if we can accommodate that many people on our water system,” Eby said.

He added the Ford government’s decision is an affront to taxpayers who paid for the active transportation that connects the built-up centres across the region. Now residents will be pulled into development away from these transit corridors — increasing vehicle use and the air pollution and carbon emissions that come with them. “That’s a horrendous thing to do to taxpayers,” he said. “And it makes no sense. The government sets the rules, we follow the rules and then they change the rules. That’s the thing I find most offensive.”

Wellington County, made of two rural towns and five townships 95 kilometres west of Toronto, has also been ordered to allow development applications beyond its urban boundary. The growth seemed to be slated for several tiny communities, like Rockwood, Fergus and Elora.

Although it’s not clear what might be built on those lands in the future, the Wellington County urban expansions in particular are already so far from urban centres that sprawl is likely, Pothen said: “These aren’t ever going to be walkable developments.”

Belleville, a city about a two-hour drive east of Toronto, was given an urban expansion on its southeastern edge as well.

Not every municipality is upset about the province’s unilateral instruction to develop with fewer limitations. Newly elected Peterborough Mayor Jeff Leal, a former Liberal cabinet minister, told The Narwhal he “welcomes the province’s approved plan for his city, which opens up certain rural and employment lands for residential development without any limits.”

“We always have to remind ourselves that municipalities are truly creatures of the province of Ontario, and this government has been bringing a series of policies they want us to follow,” Leal said. When asked if he believed the province was subverting local decision-making, Leal said the province’s decision would help Peterborough solve its housing crisis, and quickly. The official decision, for example, doesn’t expand the city’s urban boundary but does open up large sections of green space for development decades earlier than intended.

Under the old official plan, Peterborough had set aside swathes of land for rural use, with the caveat that it would likely be opened to urban development after 2051. The province’s version strikes that out, meaning those lands can be — and, given the Ford government’s development push, seem encouraged to be — built on as soon as possible.

Leal believes it is possible to “develop our own local approach to the provincial-wide legislation.” What that looks like will depend on the details and recommendations of Peterborough city staff, who are still reading and absorbing their new plans as well as the recent changes to the provincial growth plan.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Governments of the two provinces have eerily similar plans to give themselves new powers to...

Katzie First Nation wants BC Hydro to let more water into the Fraser region's Alouette...

Premier David Eby says new legislation won’t degrade environmental protections or Indigenous Rights. Critics warn...