Water determines the Great Lakes Region’s economic future

Climate change, geopolitics and business opportunities power a blue economy

In mid-October, the air in Meaford, Ont., was in that magical in-between period — a slightly warm, apple-and-dew-tinged fall breeze pushing against a blue-grey sky on the cusp of winter. Yet many who live and farm on the escarpment that overlooks the 158-year-old town kept saying that “something stinks.”

They don’t mean that literally. For many of the 11,000 people that live there, Meaford is perfect: a tiny, untouched, unindustrialized town on the southern coast of Georgian Bay. That water is their jewel, a deep, colossal pool that would be the fourth largest lake in Canada if it wasn’t just a bay that links to an actual Great Lake: Huron.

To the east of Meaford, the rugged coast of the bay disappears into the horizon, bordering some of the largest wetlands and longest freshwater beaches Ontario has to offer. There are no tall, man-made structures on the horizon. Not a transmission line, pillar or pole in sight. To the west of the town, the shoreline is flanked by a clay-and-limestone escarpment — the only landform on the bay’s shoreline distracting from the water. It’s covered in a hue of autumnal trees broken up by roadways that lead to the bay, carrying fishermen, swimmers and sailors, as well as residents with cottages worthy of the pages of a design magazine.

“It’s quiet here,” one resident after another tells me — the kind of idyllic calm you can only find when an entire bay is your backyard. In fact, much of Meaford is a storied, historic town waiting to be discovered. Perhaps that’s why its slogan is “Set your sights on Meaford.” But now that an outsider has, many locals are nervous they will mess with perfection.

Currently, Meaford’s tranquility is interrupted by just one thing: the sporadic, booming echoes of gunshots and explosions at the top of the escarpment, at one of two Department of National Defence training facilities established during the Second World War. Up here, trees and tanks coexist in a flat, unruly woodland. When soldiers enact a live-fire battle simulation, locals say the shots can be heard all across the bay, disrupting everything from slumber to school.

But the booms are uncommon these days; the military presence is slight and dwindling. For the most part, National Defence’s 20,000 acres are in a quiet, limbo state with nature encroaching, burying even further an unknown amount of unexploded ammunition that has collected here over the last seven decades.

Since 2019, National Defence has been in talks with TC Energy to allow the company to use around three per cent of its lands to build what it calls “Ontario’s battery,” harnessing the power of Georgian Bay. Already the owner of 48.4 per cent of Ontario’s largest nuclear power facility — Bruce Power, just over an hour drive west of Meaford — TC Energy wants this to be the site of “one of Canada’s largest climate change initiatives”: a $4.5-billion energy storage project that could power one million homes for 11 hours.

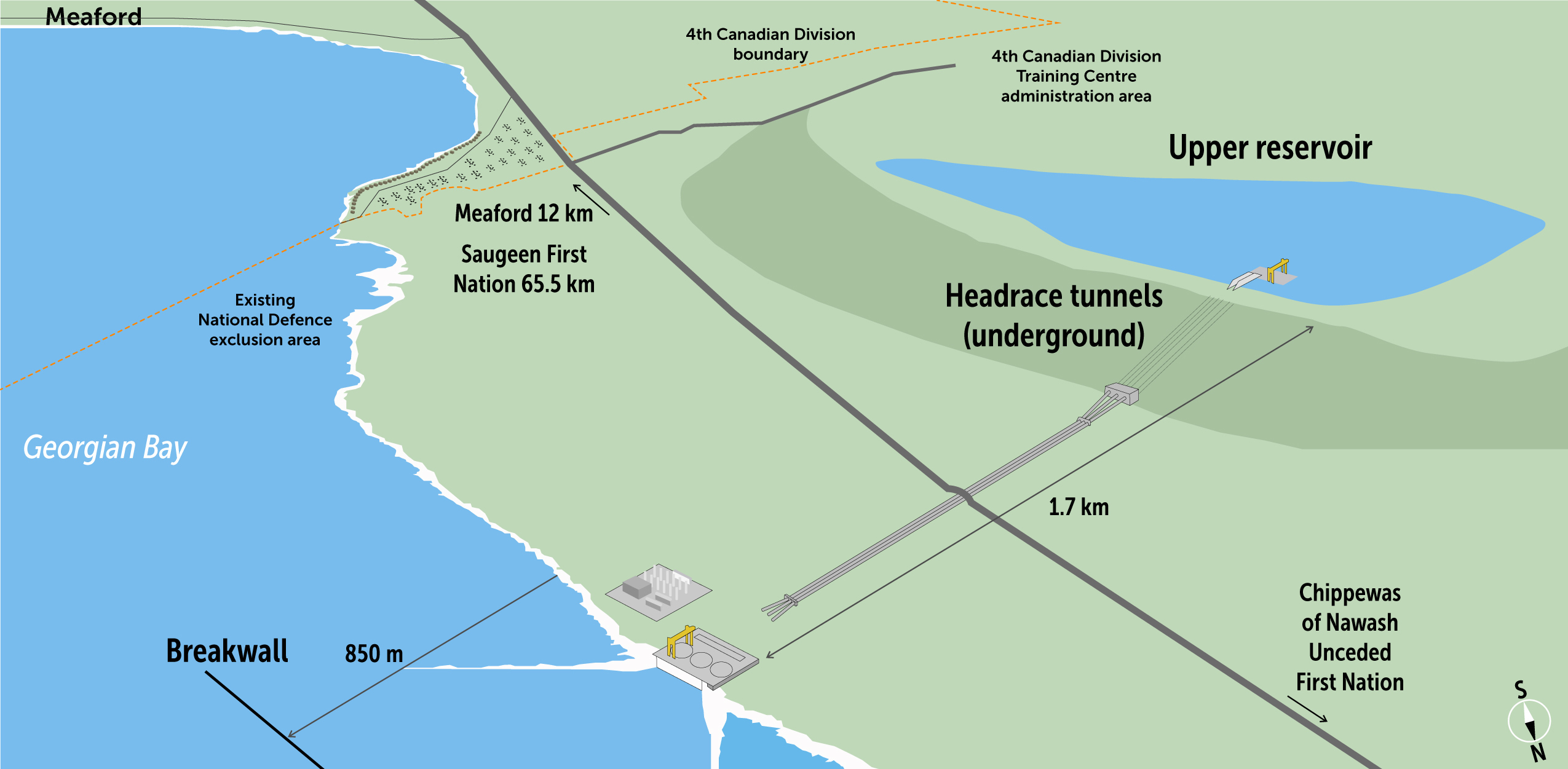

The technology is called pumped storage and has been in use around the world for 116 years. Here, it would work like this: every day, the company would draw — or pump — nearly 7,000 swimming pools worth of water out of the bay. It would move that water 150 metres up into a reservoir atop the escarpment, using excess power created at Bruce Power or perhaps from wind farms nearby. During the day, the water would pour back into the bay, rushing past turbines to generate electricity that run through underwater cables to feed the province’s grid, bringing power to rapidly growing southern Ontario.

Georgian Bay has never been disrupted by this sheer magnitude of human activity. It’s a delicately balanced ecosystem with few nutrients and a highly sensitive food web. The bay has so far remained relatively safe from pollution like excess algae. But, researchers say, the smallest of disturbances could cause the largest of disruptions. And TC Energy is not small, nor is the pumped storage facility it wants to build.

Perhaps that’s why those who live and spend time here are split between anxiety and hope, the possible harms to their beloved water facing off against the potential benefits of having a big corporation come to a small town.

Those concerned about the project worry that moving huge quantities of water into and out of the bay might impact the water’s current, its temperature, the species in and around it and the stability of the escarpment. There’s a fear that first the construction and then the operation of the project will destroy the quiet bay: a prolonged slurp when the water is pulled up and an extra long flush when it’s pushed down.

But others see opportunities, if things go well. Most members of Meaford’s municipal council are cautiously hopeful about an infusion of cash, dreaming of a renovated hockey arena and an expanded sewage facility. Saugeen Ojibway Nation also talks about possibilities of scholarships, housing and a genuine partnership with an energy company — its chiefs say TC Energy is making efforts to include them in designing the project, and time will tell if it’s “damage control” or meaningful change.

After all, the Calgary-based company is known best for building oil and natural gas pipelines — and for how the environmental risks of its pipeline projects have often been ignored by governments meant to protect people and wildlife from industry.

And right now, the Ontario government is rather desperate.

Canada’s most populated province is staring down an energy supply crunch. The provincial energy operator has said the impending shutdown of some of Ontario’s nuclear plants means that as soon as 10 years from now, daily life here could include flickering lights, intermittent power outages and spotty internet.

There’s an obvious solution: more fossil-free renewable energy, like wind and solar. But that also poses a challenge of how to capture energy from the wind when it blows and the sun when it shines to use when it’s needed most. That’s why the Ontario government has asked the energy operator to get storage solutions — like very large batteries, made of either lithium or water — running on a very tight timeline.

It may just be the perfect time for TC Energy to set up a new foothold in Ontario.

“This is, I think, inherently, a positive environmental story,” John Mikkelsen, TC Energy’s director of power and energy solutions, says. He believes pumped storage makes sense for a province with a lot of water and a looming energy shortage. “This project will enable Ontario to move off fossil fuels.”

“It’s a signature project for us to demonstrate our commitment to the energy transition,” Mikkelsen says. But given that TC Energy is still heavily invested in oil, gas and pipelines, not everyone is convinced environmental protection is top of mind.

To piece together four years of debate about the company’s proposal, The Narwhal interviewed dozens of Meaford residents, local politicians, several energy experts across North America and multiple Great Lakes researchers, as well as First Nations chiefs who spoke publicly about the project for the first time. The Narwhal also reviewed 2,000 pages of National Defence documents obtained through freedom of information legislation by Meaford residents. They reveal possible environmental impacts to the military lands if the project goes ahead as proposed, potentially including the permanent loss of 10 per cent of the species living on the project site and contamination of land and water by unexploded ammunition buried there.

What this all illustrates is a complicated story traversing an ever-evolving conversation about how projects designed to help the environment can also cause it harm — and who and what gets to balance that scale. The pumped storage proposal for Meaford has sparked a big question: can one of Canada’s largest oil and gas corporations deliver clean energy without putting Georgian Bay at risk?

Like so many questions, the answer depends on who you ask.

From a boat, the foot of the escarpment looks luxurious: a row of cottages ranging from rustic to recently renovated. Halfway along the shoreline, cottages stop and trees begin, separated by an invisible boundary between public and military space marked solely by a bright red “Out of Bounds” sign. The gravel road that leads to these houses is interrupted by a different kind of red message. “Say No,” the signs stuck in the ground say. “Destroying Blue Does Not = Green.”

A number of Meaford residents opposed the project as soon as TC Energy proposed it in 2019. They insist it wasn’t a knee-jerk reaction against the idea of storage — just the location of this one, and the company running it. Tom Buck, for instance, is repeatedly clear about this: he’s not against clean energy and this isn’t another not-in-my-backyard scuffle.

“No, no, this is different,” Buck insists. “This is about the big, blue thing in front of me and the company that wants to hurt it.” His eyes glimmer as he marvels at how the bright blue sky fades into the indigo water, not a ripple in sight. “Just look how clear it is.” And he’s right: there really is something magnetic about the bay.

Buck spends half the year in Meaford, with plans to spend the rest of his life here. The former mayor of Farmington, Mich., inherited his home from his father, who spent every summer with his grandparents on the town’s beaches. “He loved this place so much he wanted to be right there, kind of looking over all of us,” Buck says. His father is buried halfway up the escarpment near his family’s almost century-old stone cottage.

A dynamic personality with seemingly all of Meaford in his phone contacts, Buck has spent the past four years heading Save Georgian Bay. It’s an organization of cottagers, farmers, retired engineers and parents that mostly live on the escarpment in what they’ve dubbed “the impact zone” — the land right below TC Energy’s planned reservoir, or what Buck calls “the dark side of the project.”

To them, the project is an impending environmental disaster. TC Energy’s maps of the project detail the creation of a 30-metre deep, 375-acre wide “large pond,” which Save Georgian Bay members suggest, by their own calculations, would impact 300 homes of about 1,000 people if it leaked or ruptured.

Pumped storage has been around since 1907 and there has only been one recorded burst of a reservoir in the way some Meaford residents fear. But worry still plagues Allister McKay, whose over 70-year-old farm is closest to the escarpment. His cattle graze right under the planned reservoir. “I didn’t know they were building that close,” the elderly farmer says. “If that thing overflowed, well, that’s that.”

TC Energy’s plans for the pond include a closing akin to a sink plug at the bottom to allow water in and out. The pond will be linked to the bay by a large pipe that the company’s plans say will “gently” pull water up and down. At the lakebed, the pipe will be covered by “permanent fixed screens that will stop aquatic life from entering,” as well as sensors to control the speed at which water is released into the bay to minimize disturbance to the environment.

The plans also indicate a number of “fail-safe” features to control water in the reservoir, including spillways to return it to the bay if levels ever near capacity.

While the company has assured Save Georgian Bay the project will not be visible from shore, the community group fears it will still be disruptive. Most of the group’s concerns are based on the sheer magnitude of the project, not recorded precedent. They believe the drilling into the clay escarpment could cause rocky avalanches into the bay. They worry the water might change temperature before it flows into the bay, which has been the case with hydroelectric reservoirs, altering the ecosystem. The project could release electromagnetic waves that spur health issues. They fear every up-and-down movement may cause a mini-earthquake-like shaking of the land.

If that last one were true, Bob Baranski would notice in his newly-renovated cottage on the foot of the escarpment. His land is separated from the military property only by a big wired fence with a big “no trespassing” sign.

Baranski has pored over TC Energy’s maps and designs, noting that his place is closest to the planned location of the pipe transferring water from the bay to the reservoir and back again. He believes he’d literally feel, hear or see the project from his dock or his floor-to-ceiling windows: that the water colour and clarity would change, maybe the flow too.

“I don’t have proof of that, these are just my thoughts,” he says. “Energy projects like this one shouldn’t be this close to people’s houses.” At the very least, those people should be consulted, which he was not. Baranski learned of TC Energy’s plans from a sticky note posted on his door by a neighbour, asking if he’d heard about “the giant power plant they’re building beside you.”

Mikkelsen says Meaford is an “ideal” location for this kind of project in Ontario. In an email, he outlines why: the site is in close proximity to the electricity grid, with perfect elevation, an existing water body and limited public access. None of his responses or TC Energy’s maps mention the homes under the project’s shadow.

Mikkelsen has been with the company for more than 19 years and is ready to debunk every concern. The project will not change the temperature of the bay because the water simply moves up and down, he says. That movement will be unnoticeable and silent because the tunnel will be deep underwater and the water will be released horizontally, consistent with the bay’s flow. And the company is working on a “comprehensive plan” for construction, including geological studies, that will prioritize the health and safety of residents and the escarpment, he says.

But Baranski, McKay, Buck and dozens more who live there remain unconvinced despite four years of informational sessions and coffee chats with Mikkelsen and others at TC Energy. Buck calls the idea “an experiment that is risking Georgian Bay.”

“We continue to discover things that don’t seem right about this project,” Buck says. “Week by week, there’s something.”

“Like all the unexploded bombs buried up there,” says Baranski, gesturing to the lands above his cottage. “This just doesn’t pass the smell test.”

While Save Georgian Bay is motivated by the worst-case scenario, the chiefs of Chippewas of Nawash and Saugeen First Nations — Greg Nadjiwon and Conrad Ritchie — have spent the last four years trying to envision the best-case outcome. These two independent communities work together as Saugeen Ojibway Nation on issues that affect the larger territory.

The unceded lands of the Chippewas of Nawash are an hour-long zig-zag drive away from Meaford: lefts and rights and deep curves along the coast, then through farms full of cows, sheep, horses, large dogs and at least one miniature horse. Continue through corridors of trees and you’ll end up at the unceded lands of the Chippewas of Nawash. The bay is here too, but peeking through bushes. This part of the shoreline is largely undeveloped — a stark contrast to the cottages in Meaford, where a few residents wondered in hushed tones what the two Ojibway nations think about TC Energy’s project.

Here, there are trailer parks and modular homes. There’s a half-built hockey arena, a community garden and several neighbourhoods that are just sprouts of housing, foundation freshly laid.

“We’re playing catch-up,” says Nadjiwon as he drives around the community, explaining every structure. He’s the senior of the two chiefs — a tall, imposing figure whose last name is heavy with history, representing a lineage of Ojibway leaders that for generations have shaped the peninsula they call Neyaashiinigmiing, meaning “point of land surrounded on three sides by water.” Settlers know it as Cape Croker.

His love and respect for the bay is moving: he says he spends time here “every opportunity it calls.” Well before the TC Energy proposal, their people launched ongoing studies to tag and track fish, the same fish Nadjiwon harvests for Elders who cannot.

Ritchie is a brand new chief, eager to usher in change. And major changes have been seen over his short tenure: this April, ownership of the eastern boundary of Sauble Beach, just west of Meaford, was returned to Saugeen First Nation after it won a long legal battle.

Both chiefs have largely kept their thoughts to themselves, perhaps aware that in their decision rests the final fate of this debate. If they approve, TC Energy pushes on. If they disapprove, TC Energy leaves. “We’re not doing this project without them,” Mikkelsen says. “We’ve put it in writing: we will not do this project if we don’t have the support of the Saugeen Ojibway Nation. We will walk away.”

In 2019, TC Energy executives approached both chiefs to talk about creating energy at Georgian Bay. “They were the first community we met,” Mikkelsen says. The company had just announced its $4.5-billion pumped storage plans for Meaford, after selling three Ontario gas plants for $2.8 billion.

Fittingly, that first conversation was at a conference about free, prior and informed consent — the responsibility of industry and governments to meaningfully consult Indigenous Peoples about development on their territories, and receive consent and agreement on resource-sharing before embarking on any projects. It’s a right guaranteed in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which Canada has adopted but Ontario has not.

“I didn’t know [the TC Energy executives] at all,” Nadjiwon says about that first conversation. “They just had this idea about stored energy.”

As far as energy stories go, Indigenous Peoples are often an “afterthought,” Ritchie says. The two chiefs know what it’s like when a community’s wishes are ignored to build energy infrastructure: their nations weren’t asked when the province put the Bruce nuclear power plant on their territory in the 1960s, or when it sold the plant to TC Energy, a couple of pension funds and power unions in 2015, instead of them.

But that story is changing. There are multiple Indigenous-led and -owned power projects emerging in Ontario and over the last several years, the province’s energy operators have made efforts to partner with First Nations on new projects. In 2013, Saugeen and Chippewas bought a third of the transmission lines running from Bruce Power to Milton, Ont.

So, like many Indigenous communities in Canada watching a surge of energy investments, their nations are thinking about how to receive a portion of the charge — both electrical and financial.

“Our authority was recognized and acknowledged from the very beginning, the way things should have been with every project in our territory,” Ritchie says. “We were involved right from the get-go, not an afterthought, in helping shape, design and plan the project.”

“In a way, we were part of the narrative. Nobody was creating the narrative for us.”

Save Georgian Bay and the two chiefs might be approaching TC Energy differently, but their goals are the same: to minimize harm to Georgian Bay. To achieve this, the community group has time and money to spend. To boost its influence over the fate of the project, it has hired a consultancy group to help develop a communications strategy and codified Save Georgian Bay as a non-profit, able to collect donations and issue tax receipts.

Meanwhile, Ritchie and Nadjiwon say engaging with TC Energy is their best way to protect the bay. They also acknowledge that part of why they are trying to work with the company is it could mean education, training and social services for their nations, not to mention housing. “We’re not naive. We’re stewards,” Nadjiwon says. “Usually, what we find and say falls on deaf ears. This time is different.”

The chiefs estimate they’ve only examined five per cent of the design and agree there’s a lot more to review and understand. But after generations of being subjected to “a position of dependency” and serving as “administrators of our own misery,” Nadjiwon says consultation is welcome if it protects the bay. Saugeen Ojibway Nation’s first requirement is to conduct its own environmental assessment.

TC Energy receives a federal permit to conduct studies to determine if the 4th Canadian Division Training Centre in Meaford, Ont., is a suitable site for pumped-water energy storage.

Saugeen Ojibway Nation begins discussing the proposal with TC Energy, which also holds its first information session for Meaford residents.

National Defence says a pumped storage project could be accommodated on the site if construction and operation don’t interfere with military operations.

Save Georgian Bay lobbies against the project during Meaford’s municipal election.

Along with the nation’s study, TC Energy expects to undergo a provincial environmental assessment, triggered by the building of the underwater transmission line. There will also be a federal accounting of environmental risk, which the Impact Assessment Act demands of projects built on federal lands. In an email to The Narwhal, the defence department said that the impact assessment process “considers a wide range of potential issues including impacts of the project on fish and fish habitat, migratory birds, as well as potential impacts on Indigenous treaty rights.”

The company already has conditional approval from National Defence to assess the site for the project, while the federal department conducts its own study. Mikkelsen says a “rigorous and transparent” study will begin in January 2024 and will last three years. No construction will begin until all concerns, including environmental, are fully addressed, he says.

There is a calm but ever-present note of caution in both chiefs’ voices when they talk about TC Energy in Nadjiwon’s office, surrounded by maps of their territories and pictures of their ancestors. While they repeatedly say the company is working well with them, both recognize attempts to forge a good relationship are partially what Nadjiwon calls “damage control” to fix a “not-so-pleasant history” with Indigenous communities and environmental harm.

Across North America, TC Energy is known for pipeline projects — some cancelled, some ongoing, many riddled with controversy over environmental hazards. Last December, for example, its Keystone pipeline, which connects oil producers in Western Canada to refineries in Texas, spilled almost 13,000 barrels of oil in rural Kansas because of faulty welding.

In northern B.C., it is finalizing the Coastal GasLink pipeline, the route of which cuts through the territories of 20 First Nations as it carries methane-heavy natural gas from near the Alberta border to the western coast for export. The B.C. government has fined the company more than $800,000 for failing to fix dozens of environmental violations along the Coastal GasLink route, including those that threaten waterways and salmon habitat. But both the provincial and federal governments have also seemed hesitant to use their full powers to enforce compliance.

While some First Nations along the route have signed agreements with the company, the opposition of Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chiefs to the Coastal GasLink pipeline has also drawn national attention, particularly the multiple arrests of land defenders. TC Energy did not receive the free, prior and informed consent of the Hereditary Chiefs, who never surrendered the rights and responsibilities to govern the 22,000-square-kilometre territory — rights affirmed by the Supreme Court of Canada in the landmark Delgamuukw decision. Yet the project was approved by the B.C. government: although it did impose conditions intended to protect the environment, TC Energy has repeatedly failed to meet those conditions, resulting in flooded lands, murky rivers and scarred wetlands.

This reputation is at the core of a deep mistrust of TC Energy among the members of Save Georgian Bay — talking to The Narwhal, one resident called the company “that big, bad pipeline builder.” And with that pipeline builder valued at over $50 billion, opponents of the project believe the company might be using its money to get people on board.

For months, there have been rumours in Meaford that the First Nations have endorsed the project and agreed to accept money from TC Energy, which isn’t entirely wrong, but as is often the case with rumours, they lack nuance.

“When we learned about the project, the first thing that came up wasn’t money, but the environment,” Ritchie says.

That said, TC Energy has put forth a number — “we set a pretty high buy-in. I’ll go as far as to say, it will be a game-changer for us,” Nadjiwon says. While it hasn’t been said publicly, Mikkelsen told The Narwhal the First Nations will have a “significant equity ownership” in the project that will ensure they have management roles and profit.

“We’re doing this together,” he said, calling the relationship “one of the most fulfilling things in my career.”

But the chiefs remain cautious. “If this project were to cause damaging and detrimental impacts … we would walk away,” Nadjiwon says. “But, here, we’re addressing the concerns, as much as technology will allow.”

While the chiefs are guarded about financial dealings, Meaford bears plenty of evidence of TC Energy’s dollars. Over the last four years, the company’s name has become an easy-to-find Waldo in town, appearing on hockey jerseys, in newspaper ads and on banners at charity runs and fundraisers in bowling clubs and churches. It has even sponsored local environmental initiatives, including the Great Lakes Plastics Cleanup.

“There is an expectation, I think, from any community that hosts any kind of project anywhere that the community receives the benefits associated with that,” Mikkelsen says, calling it “an important part of being a good neighbour, a trusted partner and an employer of choice.”

But the benefits began before Meaford’s official OK, and members of Save Georgian Bay say the company has “invaded” their community trying to win over the town. Some worry it’s working on local politicians.

In July, the town hired two consulting agencies — StrategyCorp and Ainley Group — to conduct a review of environmental studies and negotiate annual community benefits: right now, TC Energy’s offer is $1.5 million in lieu of property taxes, which Meaford is considering. The cost of hiring these agencies is estimated to be more than $3.5 million, paid by TC Energy, according to an Oct. 30 staff report. The company is also footing the bill for the city’s special legal counsel and negotiator on the project.

This flow of funds seems suspicious to some, given that one of the project’s early opponents is now a staunch supporter — Mayor Ross Kentner.

As a councillor, Kentner was wary of the project, concerned about lack of consultation and whether the project was as green and efficient as advertised. He wrote a letter to National Defence expressing all this, and campaigned on his opposition to the project. But after his victory as mayor in the 2022 election, Kentner changed his mind.

“There are many reasons for this,” Kentner, a former local radio personality, says in his distinct broadcaster voice. Kentner says he was convinced after talking with other municipal leaders, as well as Energy Minister Todd Smith. All of them persuaded him that Ontario’s energy needs grew drastically over the pandemic and are only getting bigger, and that “Meaford needs to try and play its part” in finding a solution.

The mayor is upfront that he believes money matters, and that partnering with a large entity like TC Energy could offset pressure on council’s coffers. The Doug Ford government is heavily pushing municipalities to build housing and Meaford could use the financial help. Industrial taxes and grants could renovate roadways and help expand wastewater infrastructure.

“With every project, that’s the case: there are community benefits,” Kentner says. He deferred queries about how the town defines or uses these benefits to the Ainley Group, which confirmed to The Narwhal that it is working with the town but didn’t answer specific questions. “If this region is Ontario’s new clean energy frontier, Meaford needs to fight for its fair share.”

Kentner and councillors in favour of the project are quick to state the limitations of their influence. The military, higher levels of government and TC Energy all have more power and resources than tiny Meaford. “I’m a bit of a pragmatist, I think [the project] is very likely to happen whether we like it or not, and Meaford needs to be there,” Kentner says.

Meaford’s position on the project does matter though, at least theoretically. Twelve years ago, a Liberal provincial government lost its majority after two gas plants planned for unwilling communities were quietly cancelled. In the aftermath of the gas plant scandal, one Liberal staffer went to prison and the plants — one of them contracted to TC Energy — were relocated to towns that seemed happier to have them.

Lessons learned from the biggest energy scandal in Ontario’s history are surely at play now. As Smith moves to approve more gas plants to face the energy crunch, the energy minister has said none will be built without municipal approval, calling support a “requirement.” He’s on record saying consent matters for clean energy projects, too.

Smith was a member of a cross-party committee that released a study into the gas plant scandal, which found that over 80 municipalities that opposed wind projects ended up home to turbines anyway. The report suggested the province require companies that want to build energy projects to “[demonstrate] that they already have community support.” It also said Ontarians deserve “transparency and openness” in the site selection process.

In a brief conversation with The Narwhal, Smith put the responsibility of ensuring local support on TC Energy, saying he believed the company has been “very involved in working with the community … very, very involved in getting municipal support as well for the project.”

“They’ve done a good job,” Smith said, noting TC Energy has made design alterations to address environmental concerns. The minister did not respond to additional questions about the risks posed by the project, which he is expected to decide on by the end of the month.

Meaford city council votes to conditionally support the project, pending TC Energy passing provincial and federal environmental assessments.

WSP Canada is awarded a $105,000 contract to conduct an environmental assessment of the site, to be paid by TC Energy.

Ontario Energy Minister Todd Smith is expected to approve pumped storage projects in Marmora and Meaford.

TC Energy’s planned operation date for the storage project on Georgian Bay.

Buck says a mid-November trip from Meaford to Queen’s Park to meet the energy minister didn’t make the government’s evaluation process less opaque. In Buck’s view, Smith and his staff prioritized energy concerns over environmental impacts, shunting responsibility to regulators and environmental groups and, Buck says, “trusting TC Energy … to do a fine job.”

“I felt a little dampened coming out of the meeting,” he says. “We felt a little bit dismissed.”

Ontarians’ distrust of how energy decisions are made is something Mikkelsen seems hyper aware of. “One of [TC Energy’s] key goals is transparency … making sure these issues of trust and other things are addressed at the front end of the project.” There’s a calculation in his remarks: history shows lack of local opposition smooths the path to government approval.

“We have a project that, I think, has a very strong support … which is very useful as you move through the regulatory process,” he says. “We think we’ve addressed, for the most part, any of the concerns we have, and we think we have a very minimal environmental footprint at the end of the day.”

Kentner believes offering a conditional yes prioritizes “minimal damage, maximum benefit.” In its statement expressing willingness, council made that contingent on TC Energy passing “any applicable environmental and/or impact assessments” and guaranteeing long-term protection of the bay.

The mayor says a partnership would allow Meaford to have some oversight over the most disruptive aspect of the project: the construction, which will take four years. The town could control when trucks travel, how many enter the escarpment at one time, how much material they carry and so forth.

Still, Kentner’s change in position is seen as a deceptive flip-flop by the Save Georgian Bay members who voted for him.

The group pressed every democratic lever available to try and sway the vote against TC Energy. Despite fears of COVID-19 exposure, members went door-to-door to collect over 3,000 signatures against the project, meaning a third of the town — homeowners and seasonal residents included — publicly stated it wanted council to vote no. Council meetings about the project were held in Meaford Hall, a 114-year-old opera house with a capacity of 3,000, and even that wasn’t big enough.

Emails, phone calls, letters: Save Georgian Bay did it all. Council still voted against them.

Buck is almost hesitant to talk about his role in this narrative, aware of his privilege and dual citizenship. “To some degree, I know we’re background noise,” Buck says, with a hint of frustration. “But I also think we’re right.” The promise — and reality — of clean energy projects impact everyone in Ontario, so it shouldn’t matter who is opposing the project, he argues, but why. And Save Georgian Bay has evidence to back up its concerns.

In July, Save Georgian Bay received 2,000 pages of National Defence documents through freedom of information legislation, which it shared with The Narwhal. The documents show four years of internal assessments of impacts, including contamination from undetonated explosives from years of live-fire training. There are also notes from dozens of meetings with TC Energy.

Though many of the pages are redacted, the documents show officials note multiple times that even if the Defence Department gives TC Energy a clear green light, the federal environment minister would have to weigh in.

In the email to The Narwhal, a defence spokesperson said multiple federal departments will contribute opinions on the project, with the Impact Assessment Agency involving “Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, Health Canada, Parks Canada (for archaeology and heritage), Environment and Climate Change Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Transport Canada, as well as relevant provincial government stakeholders.”

The environmental risks listed in the documents obtained by Save Georgian Bay are many. They show defence officials have identified “potentially up to 30 federally-protected species at risk” on the Meaford site that may be impacted by construction of the reservoir. One is the western chorus frog, the same animal whose presence is one reason Environment Canada has paused the Ford government’s Highway 413 project for years.

The documents list multiple harms that seem unavoidable with such a project. Officials note it “would require the destruction of the woodlot habitat.” They also document likely “adverse impacts on fish and fish habitat” from discharging water into the bay, which could require Fisheries and Oceans Canada to step in. There are also worries that the water discharge could cause “new erosion” and “increased water flow in areas that are inadequate to handle the volume.”

Defence officials repeatedly note the project is estimated to “devastate” at least 10 per cent of the wildlife on the site, including migratory birds. Some species are unidentified as the military can’t assess terrain in the danger area as “no one has stepped foot in that area due to the extremely high [unexploded ordnance] threat.”

The explosives buried all across the site are identified as a major worry, and cleanup would be a requirement for any project on these lands. Officials note explosives likely contaminated the soil with heavy metal toxins: “disturbing the soil” or using it to build the reservoir could contaminate land and water, potentially harming the health of the bay’s wildlife as well as the health of humans who get their drinking water from it — which is everyone around the bay.

At multiple instances, officials note that TC Energy has “limited to no experience” working in ammunition-filled areas: “[National Defence] expressed that they have concerns with [TC Energy’s] proposed location given their lack of [unexploded ordnance] expertise, given their history of projects.”

Defence officials were of the opinion that the company has not properly factored cleanup into its planning, which would be a significant expense that could extend the proposed four-year construction timeline by up to a decade.

“This could be a showstopper,” officials say.

When asked by The Narwhal how many undetonated explosives are on the site, a defence spokesperson replied via email that “it is very difficult to provide a tally and type of ammunition” since the site has “been in continuous use for military live fire training since World War II. It is reasonable to expect that the types of ammunition that could be found … include any and all ammunition that has been used by the Canadian army during that period.”

Presented with the information in the documents, TC Energy’s Mikkelsen says the company has collected three years of data to understand all the environmental risks, which will be made public in the official assessment process, expected to begin in early 2024. He says the company will “mitigate and avoid” any impacts to species — “that’s a normal aspect of any project anywhere in Canada.”

When asked by The Narwhal about how documented harm to water and species on other project sites has hurt the company’s reputation, Mikkelsen said he believes this project has been “very different.” He launches into a long list of everything TC Energy has done: from preliminary studies to public conversations.

He zeroes in on design changes he says were made after hearing local environmental concerns. One of the monitoring structures has been moved away from the shoreline and the tunnel’s opening has been buried underwater. Transmission lines across the bay were axed in favour of underwater cables. The speed of the water discharge has also been slowed down.

One of the more notable changes, Mikkelsen says, is the decision to include screens on the underwater tunnels to stop fish from passing through. Nadjiwon says when he and Ritchie told TC Energy they were worried that water being pumped up to the reservoir would kill fish, the company added the screens and plans to “fine-tune that further.”

Mikkelsen says this change was also a lesson learned from Ludington, Mich., where one of the world’s oldest and largest pumped storage projects — also built on a Great Lakes basin — had a detrimental impact on aquatic life. By one estimate, 150 million fish were killed every year in the first decade of operation, drawn through the turbines as they passed through the tunnel. One lawsuit and a US$172-million settlement later, the project now features a similar net stretching 2.5-miles, or four kilometres.

While Ludington is not Meaford, Mikkelsen believes studying the Michigan project was “instrumental in the state-of-the-art design that we are proposing, that will significantly improve the protection of fish, fish habitat and the water quality of Georgian Bay.” In fact, Mikkelsen believes all the design changes are “radical” because they demonstrated the company was “actually listening and incorporating the feedback.”

“I think you have to build trust and I think the changes to the design had two effects: first, it addressed the issue directly, and second, it demonstrated to anyone that was paying attention that we listen,” he says.

In response to The Narwhal’s questions about the assessment of risk in the Department of Defence documents, he says the company is working with experts that study unexploded ordnances. Mikkelsen believes cleanup of the explosives is doable and will have “a positive environmental impact as a result of this project.” He says the company does not anticipate any delay because of past military activity.

According to National Defence, “The discussion surrounding the responsibility for [unexploded ordnance] clean-up, with a focus on preventing soil contamination and protecting wildlife both on land and in Georgian Bay, is ongoing [and] will feed into any future agreements that may be put in place should the project move forward. …” The email from a department spokesperson said that ”The commitment of the Government of Canada to addressing concerns and mitigating potential impacts remains unwavering.”

As to the broader concerns of residents, Mikkelsen says much is still being figured out. Construction plans, he says, will be created with community consultation. Future geophysical studies will mitigate physical disruption to the escarpment. “We are conducting comprehensive computer modelling studies to validate that the design avoids negative environmental effects to Georgian Bay,” he says via email, reiterating that any environmental concerns will be addressed before the project moves forward.

In the absence of these answers, Buck and co. remain skeptical. “The company has made a lot of promises, including a promise to do no harm, but they can’t explain how they won’t do more harm,” he says. “They think they can build a perfect project. I know they can’t.”

Save Georgian Bay aren’t alone in this sentiment. “I have mixed feelings,” says Adam Scott, an energy and environment consultant who grew up around Georgian Bay and knows it intimately as both a resident and researcher. His family has lived in the area for over a century and his parents are still on the other side of the water, opposite the escarpment where the project will sit. “I’d normally be supportive of a project like this but I’ll admit: I don’t trust TC Energy. As a company, they have a really bad record,” he says, pointing to Keystone’s spill history as one reason he doubts the power behemoth is acting in good faith.

Scott’s research into TC Energy’s record includes visiting communities during the proposal stage of Energy East, an oil pipeline that would have run from Alberta to Eastern Canada, but was cancelled. Scott says that as he went from community to community, he learned the company had “sprinkled” money on city councils along the route, money he says local officials can be hard pressed to refuse when it’s for “things a community needs.”

“The direct payments for items in advance of project approval is problematic,” Scott says.

But, again, Mikkelsen says financial support for even potential host communities is just the way things work with big energy projects. “At TC Energy, we believe seeing is believing,” he says, highlighting all the ways the company has changed the design after its community consultations.

Scott points out, though, that there has been no independent, impartial review of the project as of yet, no thorough environmental study that would persuade him the company won’t “just vacuum up a lot of fish and harm the water.”

“Maybe I’m also guilty of not-in-my-backyard syndrome,” Scott said. “But I wish we were talking about a more cut-and-dry industrial storage project and not one that involved one of the most troubling corporations sucking up Georgian Bay and pouring it back out.”

Driving around Georgian Bay with either Buck or Chief Nadjiwon is to see the environment from a different perspective but with the same crystal focus on the water. Both stop constantly to point out various parts of the bay and escarpment that look unremarkable to an outsider but which they insist is special for a memory, a fish, a view.

The two men are deeply tied to this region by lineage and also by the deep sense of service felt by those who carry the weight of everything that can go right, or wrong. Each man knows he can’t control Ontario’s energy demands, TC Energy’s plans or the military’s decisions but still believes he can influence the conversation.

Both plan to keep doing so in the months that follow, with TC Energy very close to getting a green light from the province.

On Nov. 30, Minister Smith is expected to announce his decision on two proposed pumped storage projects. Along with Meaford, he’s evaluating a proposal in Marmora and Lake, a couple hours east of Toronto, where an old iron-ore mine pit would form one of the reservoirs for what’s known as a closed loop pumped storage system. It’s a less controversial idea since the same water that naturally fills that pit will be pumped up to a higher reservoir and poured back down through a pipeline repeatedly, never drawing from another body of water.

Although Meaford is more contentious, Mikkelsen believes the project will get Smith’s approval. “The minister likes this project because, from a social, economic, Indigenous reconciliation perspective, this is the kind of project that Ontario really, really wants,” he says. Operation will begin in 2030 if everything goes to plan, though these things rarely do.

Both Nadjiwon and Buck also know they might not be around to witness how the question at hand is answered.

“Let’s say, I’ll be fertilizing the land by the time it’s reality,” Nadjiwon says.

“I love my community. I wouldn’t do anything to put it in jeopardy,” he says softly, taking a long pause as he looks at a boat docked on the shoreline on a perfectly still day. “I can’t say anymore.”

Buck is more forceful, struck with emotion as he reflects on dedicating so much time to opposing this project. “This land cannot be offended like this,” he says repeatedly, with tears in his eyes. “It just can’t.”

As everyone waits for the energy minister to make his decision, there’s an anxiety that even the bay can’t quell. Maybe because that big, blue thing is exactly what’s at stake.

Update Nov. 23 at 10:03 a.m. ET: This story was updated to add additional comments from the Department of National Defence.

Updated Nov. 30 at 7:51 a.m. ET: This story was update to reflect that the municipality of Meaford has not yet accepted TC Energy’s community benefits offer.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Climate change, geopolitics and business opportunities power a blue economy

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

Court sides with Xatśūll First Nation, temporarily halting Mount Polley mine waste expansion