The Narwhal’s in-depth environmental reporting earns 11 national award nominations

From disappearing ice roads to reappearing buffalo, our stories explained the wonder and challenges of...

The cost to clean up British Columbia’s largest mining complex is billions of dollars higher than government and industry estimates, according to a new report. It estimates it will cost $6.4 billion to remove just one contaminant from water affected by Teck’s Elk Valley coal mines. This number is $4.5 billion higher than what the provincial government currently requires as a financial security to ensure the project owners do not leave taxpayers with the future cleanup costs of the mine.

“They’ve severely underplayed the problem and B.C. taxpayers stand to foot a multi-billion-dollar bill if anything goes wrong,” Simon Wiebe, a mining policy and impacts researcher at Wildsight, said in a press release. The Kootenay-based conservation organization commissioned the independent consulting firm Burgess Environmental Ltd. to calculate the costs of Teck’s current plans to treat water contaminated with selenium, an element that can be toxic for fish and other aquatic life at elevated levels.

The report highlights concerns that not enough is being done to address a growing pollution problem in Ktunaxa Nation territory and that mines across the province could have cleanup costs far higher than what is currently acknowledged by the provincial government. It’s a gap mining reform advocates say could put the environment and taxpayers at risk if mine owners go bankrupt or disaster strikes.

The estimated cost to clean up all the mines in the province is $4 billion, according to the most recent report from the province’s chief inspector of mines. To ensure mining companies pay for the clean up before depleting a mine and walking away, the province requires financial assurance. This is returned once the company reclaims the site or as they do progressive reclamation. The amount a company has to provide is estimated by the company and reviewed by the government.

Teck’s coal mines are the province’s biggest liability with a current estimated cleanup cost of $1.9 billion. In an interview with The Narwhal, Wiebe said the report is strong evidence the amount held by the province is far below what will be needed to clean up B.C.’s biggest mines.

Teck, however, took issue with the report’s findings. In a statement, company spokesperson Dale Steeves said “the estimates provided by Wildsight are inaccurate and inconsistent with calculations made under B.C. government policy.”

“Their use of simplified assumptions overstate ongoing water treatment operating costs alone by 50-60 per cent,” he said. Steeves added the report’s approach is inconsistent with B.C. government policy around capital costs.

“We are committed to meeting all reclamation obligations at no cost to government or taxpayers,” he said.

In a statement provided to The Narwhal after publication, Energy, Mines, and Low Carbon Innovation Minister Josie Osborne said ministry staff would review Wildsight’s report in the coming days.

“We regularly review reported liabilities for all major mines in the province, including those in the Elk Valley, ensuring they are consistent with our regulations and policy and are reflective of the latest site information,” she said. “B.C. is committed to ensuring that mining operators provide securities in accordance with our policy to ensure that polluters pay.”

Coal has been mined from the Rocky Mountains in southeast B.C. for more than a century. To access the coal, Teck strips away mountaintops. It’s a process that results in an enormous amount of leftover waste rock. When these massive piles of waste rock are exposed to oxygen and rain or snowmelt, selenium and other naturally occurring minerals seep into the water and flow into nearby creeks and rivers.

“Waste rock placed decades ago continues to release selenium at a steady rate today, and is expected to continue doing so for many decades more,” Teck acknowledged in its Elk Valley Water Quality Plan, which it was ordered to develop in 2013.

Selenium is an important element for all living things in tiny amounts, but too much of it can be toxic. For years, selenium concentrations in waters downstream of Teck’s mines have been many times higher than the guidelines the B.C. government established to protect aquatic life.

A key concern is the risk elevated selenium levels pose for westslope cutthroat trout, a species of special concern under the federal Species At Risk Act. Too much selenium can cause deformities in fish, such as curved spines, misshapen skulls and abnormal gills, or eggs that fail to hatch.

The B.C. government recommends the 30-day average concentration for selenium in water should be two parts per billion. In the Fording River, downstream of Teck’s mines, selenium concentrations ranged from 33 parts per billion to 68 parts per billion last year, well above the provincial guidelines.

At times, these levels also exceeded the limits outlined in Teck’s permits, which include the standards Teck is legally required to meet. In the Fording River, Teck is required to keep selenium levels to 63 parts per billion.

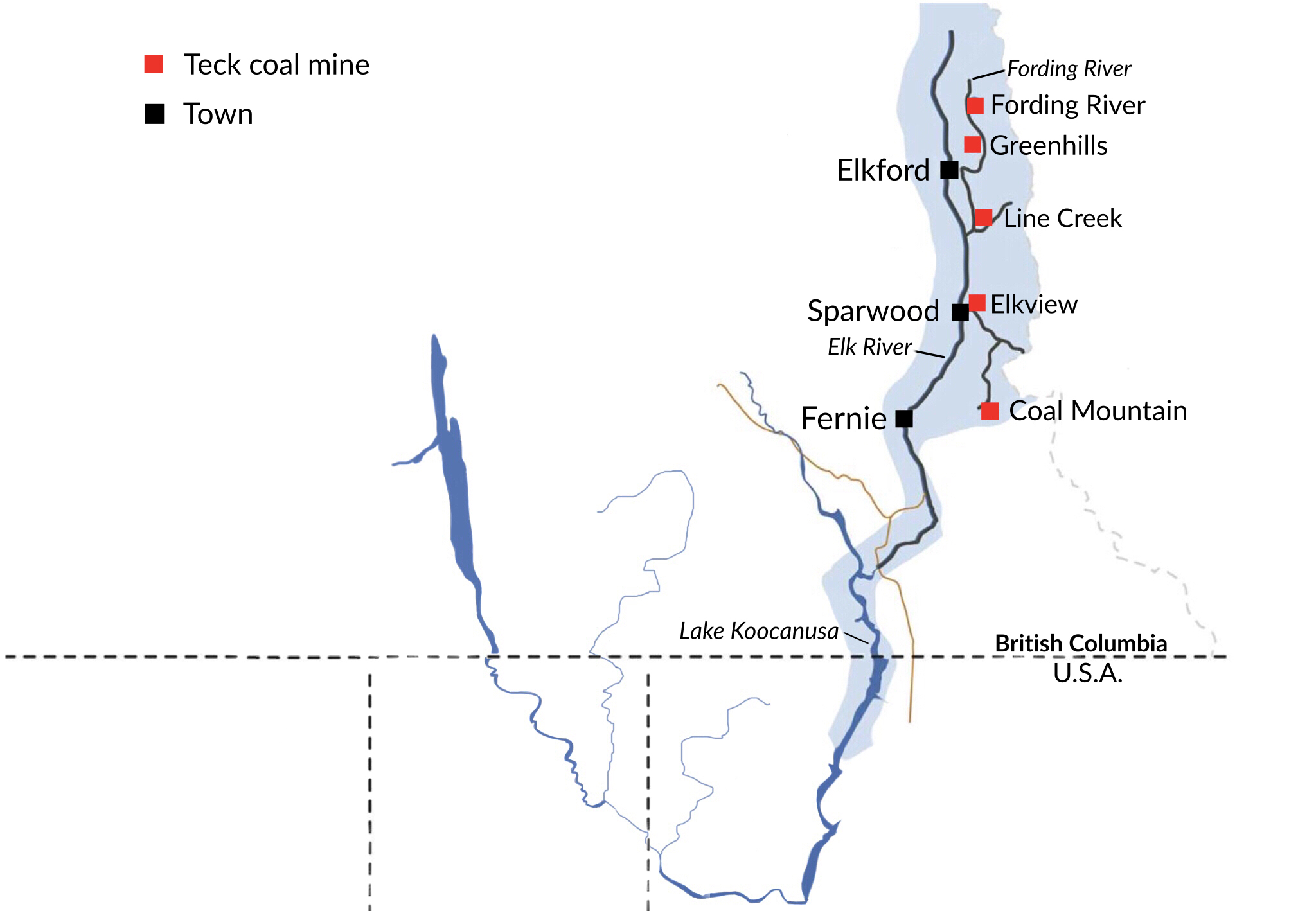

From the Fording River, contaminants from Teck’s mines flow into the Elk River, before moving into Lake Koocanusa, a cross-border reservoir, created by Montana’s Libby Dam.

While selenium concentrations in the Elk River are considerably lower by the time they reach Koocanusa, they remain above B.C. guidelines.

In 2022, the average concentration just upstream of the reservoir — and about 80 to 120 kilometres downstream of the mines — was 5.77 parts per billion, according to a recent study by the U.S. Geological Survey. Researchers found selenium concentrations at this spot increased 551 per cent between 1985 and 2022.

“The waste rock that has been produced by the mines will continue to leach this — essentially poison — for decades, upwards of centuries,” Wiebe said. “This isn’t something that is just going to go away. This is something that will have to be treated.”

Selenium contamination from Teck’s mines has become a point of contention in Canada-U.S. relations. Recently, the two countries, in concert with Ktunaxa Nation, agreed to refer the issue to the International Joint Commission, which was established under the Boundary Waters Treaty of 1909 to study and recommend solutions to intractable disputes.

In the meantime, Teck has continued to invest in water treatment and other measures to reduce selenium contamination from its mines.

The company has spent more than $1.4 billion to reduce water pollution and currently has capacity to treat 77.5 million litres of water a day.

According to Teck, its water treatment facilities remove 95 to 99 per cent of selenium from the water they treat. But the company is so far only able to treat a portion of the water contaminated by its mines.

Teck plans to build six more water treatment facilities by 2027, increasing treatment capacity to 150 million litres per day, Steeves said.

“The goal of the Elk Valley water quality plan is to stabilize and reverse the trend of selenium, protect the ongoing health of the watershed and allow for continued sustainable mining in the Elk Valley,” he said, adding the plan is working to reduce selenium concentrations downstream of the treatment facilities.

Steeves said Teck is also working to develop technology that would control the source of water contamination, “with the long-term goal of protecting water quality without the need to build and operate active water treatment facilities.”

“We have a proven track record of successfully reclaiming mine operations in B.C. and beyond, and we are committed to protecting water quality in the Elk Valley,” he said.

The $6.4-billion cleanup estimate calculated by Burgess Environmental considers a fraction of the total costs. The firm focused on selenium removal as it is, by far, the biggest expense, Wiebe said. Other costs like habitat and land reclamation and removing other heavy metals are not included.

Wildsight shared the findings from the report with the B.C. government, Teck and Ktunaxa Nation Council before it was released to the public. Ktunaxa Nation Council and the B.C. government were not able to provide a reaction to the report before publication time.

In B.C., mining companies are responsible for providing cleanup cost estimates and they’re “incentivized to underestimate,” Wiebe said. There are government guidelines and a Microsoft Excel document to standardize the process. The government also adds a 15 per cent top-up to the industry estimate. But Wiebe believes there should be more transparency during the estimation process.

“Unfortunately, a lot of this is a black box,” Wiebe said. “We don’t know what goes on.” The online calculators are out of date and not always used, he said. For the report, Burgess Environmental used public data, reports and plans from Teck and the B.C. government. The author also used other public technical analyses and visited the Elk Valley watershed this February. Teck also provided some limited data and comments to help with the calculations, Wiebe said.

Wiebe points to Nevada and Alaska as examples for B.C. to follow. In those states, reclamation calculations are disclosed and the public is invited to comment on draft estimates. This process would allow outside groups to raise concerns if they believe the estimates are not reasonable, Wiebe said. “We don’t have that option, because all we get is a total amount, once a year.” These estimates are published in annual reports from the chief inspector of mines. Wiebe isn’t satisfied with the level of transparency in B.C., where relatively little data about calculations is disclosed. “It’s really disappointing,” he said.

International mining giant Glencore is set to acquire Teck’s steel-making coal mines in the Elk Valley, subject to federal approval. In a statement announcing the deal, CEO Gary Nagle said the company was committed to “engaging in further reclamation efforts.”

The company said it “will continue to implement the Elk Valley Water Quality Plan, including by continuing ongoing research and development aimed at developing and implementing innovations to manage and improve water quality in relation to its operations.”

But Glencore’s record worries groups on both sides of the Canada-U.S. border. Last year, the company pleaded guilty to bribery and market manipulation charges and agreed to pay more than $1.1 billion in penalties. The bribery charges related to payments made approximately between 2007 and 2018 in what the U.S. Department of Justice described as a “decade-long scheme by Glencore and its subsidiaries to make and conceal corrupt payments and bribes through intermediaries for the benefit of foreign officials across multiple countries.”

Glencore also pleaded guilty to a “multi-year scheme to manipulate fuel oil prices at two of the busiest commercial shipping ports in the U.S.,” which took place between 2011 and 2019, the Department of Justice said in the news release.

Glencore spokesperson Charles Watenphul said in November the company “has taken significant action over the last several years towards implementing a world-class ethics and compliance program.”

“Glencore is a different company today and is committed to being a company that creates value for all stakeholders by operating transparently under a well-defined set of values, with openness and integrity at the forefront,” he said in November.

As of B.C.’s most recent chief inspector’s report, Glencore had provided just a small fraction of the reclamation securities for two of its five B.C. mines, leaving a future cleanup bill of more than $8.6 million.

If the deal goes through, Glencore will purchase a 77 per cent stake in Elk Valley Resources, which represents the entirety of Teck’s steel-making coal business. Nippon Steel Corporation would take a 20 per cent stake in the company, while POSCO, a steelmaking company based in South Korea, would gain a three per cent stake in the mines.

Watenphul said in November that the company would provide what it owes to the province in reclamation securities by the end of March 2024. He declined to comment on this new report and referred to previous statements to The Narwhal.

But Wiebe remains concerned that B.C. doesn’t hold sufficient security for the Elk Valley mines.

“They could continue mining until it’s no longer profitable, go bankrupt and all of a sudden it’s on the taxpayer to fund the reclamation efforts and pollution cleanup,” he said. “That’s a huge risk. It’s going to be multiple billions of dollars, at least, potentially on our shoulders.”

Updated March 19, 2024, at 5:55 p.m. PT: This story has been updated to include a comment from Energy, Mines, and Low Carbon Innovation Minister Josie Osborne

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

From disappearing ice roads to reappearing buffalo, our stories explained the wonder and challenges of...

Sitting at the crossroads of journalism and code, we’ve found our perfect match: someone who...

The Protecting Ontario by Unleashing Our Economy Act exempts industry from provincial regulations — putting...